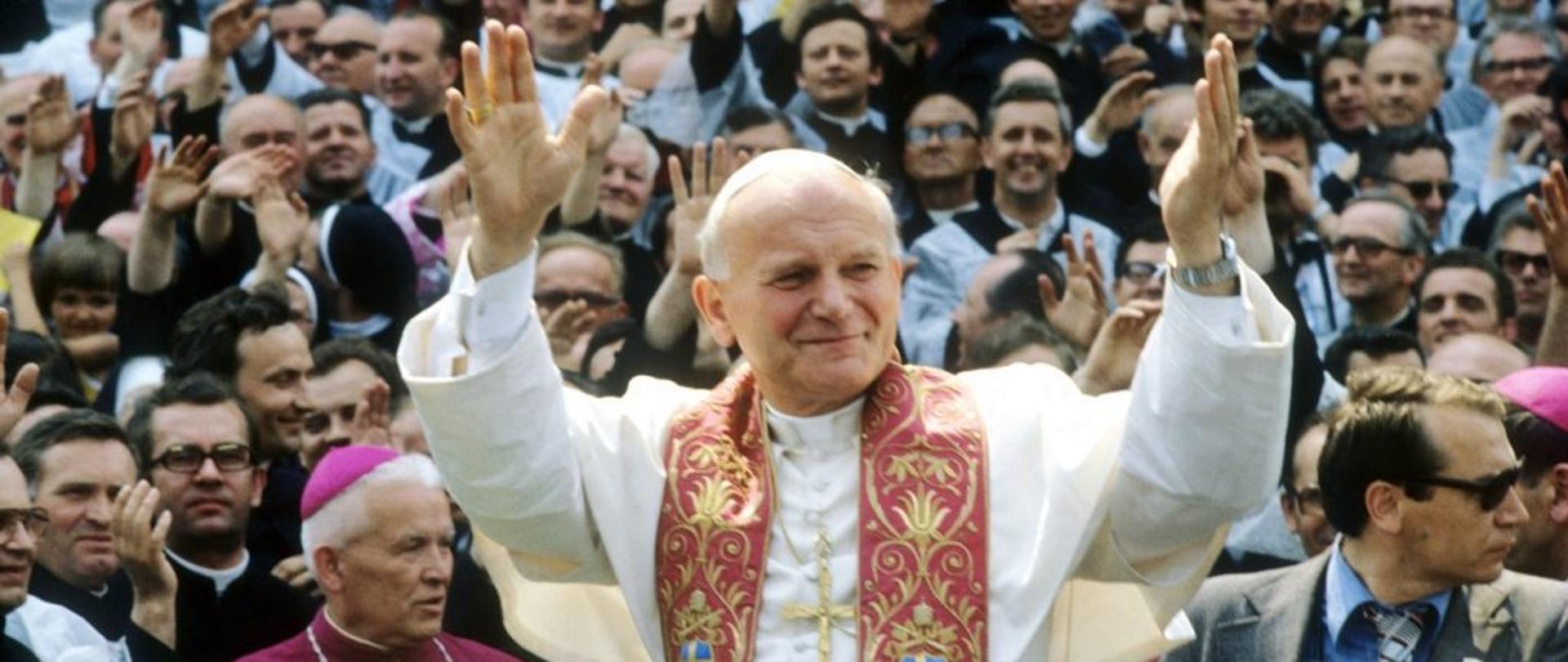

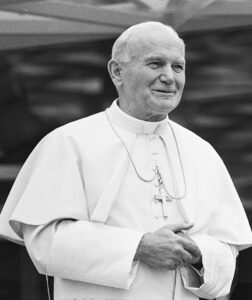

Karol Wojtyła made the papacy a global player again who could challenge the empire. Before Ronald Reagan appeared on the scene, John Paul II started star wars and the final battle against the evil empire, says Prof. Michał Łuczewski, a sociologist from the University of Warsaw.

Can we say that Karol Wojtyla, later John Paul II, was an anti-communist?

Wojtyła was not against anything. He always defined himself in a positive way. Thus he was not a born anti-communist, but a disciple of Christ, and that was the reason for his disagreement with communism. Hence, he did not view communists as enemies. It seems to me that this was the greatest danger to communism – not that one hated them, but that one loved them despite the mistakes they made.

We treat John Paul II, who came to Poland in 1979, as someone who said “Let Thy Spirit descend” and brought about the fall of communism. But in the same year he spoke about elections to the European Parliament. Who then could have imagined that Poles would take part in these elections? However, he was already thinking not only from the point of view of Poland, but also of Europe and the world. And he prepared Poland for challenges perhaps more difficult than communism. Because he was as skeptical about communism as he was about a liberal democracy that destroys the values on which it was built, such as human rights, the right to life, and religious freedom.

John Paul II knew that liberal democracy would be a more difficult opponent after the fall of communism. Communism was an open totalitarianism, and the danger of “democracy without values” lies in the fact that it can become a disguised totalitarianism (encyclical: “Centesimus annus”). Please note that many people representing his background, i.e. the Catholic intelligentsia, after 1989 very strongly supported liberalism – liberal economic reforms, liberal transformation of morals – while John Paul II loudly protested against it.

When did Wojtyła notice the threats posed by communist ideology?

Wojtyła was born in free Poland because in 1920 Polish soldiers had stopped the communist onslaught. In 1999, John Paul II visited the Cemetery of the Victims of the War 1920 in Radzymin and said: “Here, silence is the most meaningful, sometimes a word is also needed. And I want to leave a word here. You know that I was born in 1920, in May, at the time when the Bolsheviks were going to Warsaw. And that is why from my birth I bear a great debt to those who then took the fight against the invader and won, paying for it with their lives. Here, in this cemetery, their mortal remains rest. I come here with great gratitude, as if paying off a debt for what I have received from them.” Brought up in the patriotic and Catholic atmosphere of Wadowice, Karol Wojtyła could never have any illusions about communism. It was obvious to him that in a system without God, there is no place for independent nations, and that system must be a system of evil.

In 1948, Wojtyła returned to Poland after his studies in Rome. In his first parish in Niegowić, he ran the Catholic Youth Association, which was persecuted by the local secret police. One of the Catholic Youth Association members beaten up by the militia was comforted by him: “It must end sometime. They will fall apart someday. It can’t go on for a long time.” Wojtyła together with the youth of Niegowić staged the play “The Expected Guest” by Zofia Kossak-Szczucka, who was the most outstanding pre-war Catholic writer, and who after the war found herself in forced exile in Great Britain. It was a political gesture. Wojtyła, reaching for the cursed writer, whom he knew from the occupation years in Krakow, showed that even if the communists destroyed Polish culture, it still existed.

And did Wojtyła make any straightforward political speech?

He focused on pastoral work, but when one thinks earnestly, builds solidarity and defends the Church, he very quickly becomes a political enemy in the eyes of the communists. And they noticed him early on, especially since during the war he became a member of the underground organization Unia, of which the Rapsodyczny Theater was a part. In 1948 its founder, Jerzy Braun, was arrested, and Karol Wojtyła’s best friend, Mieczysław Kotlarczyk began to be investigated by the secret police as a defender of “clerical” values. Although Wojtyła himself was perceived as more and more anti-clerical, which led to the collapse of their friendship.

In the milieu that began to gather around John Paul II, there were many people against communism, also because they lost their relatives in Katyn. In order to avoid any trouble on the part of the security service, Wojtyła dressed in civilian clothes, and members of the milieu called him “Uncle”. During the culmination of the Stalinist persecution of the Church, one of the secret police agents recorded his words. It was the time of the show trials of the Krakow Curia, the time of the arrest of Primate Wyszyński: “The screw tightens and the fight enters an increasingly severe phase. What will be its result, it is known in advance. The victory can only be on our side.” These are amazing words. What strength of spirit must this thirty-year-old man have possessed, prophesying victory in the most difficult hour of the Polish Church?

In the following years, Wojtyła went higher and higher and became more and more dangerous. In one of the reports for the Polish United Workers’ Party authorities we read: “Bishop Wojtyła is fully devoted to the affairs of the Church. Despite the appearances of displayed compromise and flexibility in relations with state authorities, he is a very dangerous ideological opponent”. Then came the Millennium Celebrations, during which Bishop Wojtyła became number two in the Polish Church. He argued for the Polish workers who wanted to build a church in Nowa Huta, for exhausted people he saw in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, and he could no longer look at its poverty; for the students who followed the memory march after the murder of Stanisław Pyjas and who later founded the Students’ Solidarity Committee. 1978 was the culmination of this path. After the conclave, the communists could only foolishly console themselves that they at least got rid of Wojtyla, because in the Vatican he would be less dangerous for them than in Krakow. Well, in 1979 he reappeared in Krakow and began – as his biographer George Weigel used to say – “the final revolution”.

What, in his opinion, was the greatest threat related to communist ideology?

Anthropological error. According to John Paul II, communism did not understand who man was and tried to reduce him to what was material. But man has a soul, he cannot be understood without God, and he will never find peace and happiness without God. To develop all his possibilities, he must be able to discover the truth and act according to his conscience. The communists did not want this. By making this mistake, they condemned man to reduction, misfortune, and finally – to violence and death.

In Wojtyła’s opinion, could any of the assumptions of communism be used in the spirit of Christianity?

In his play “Our God’s Brother”, which is dedicated to Brother Albert Chmielowski, he introduced the character of the Stranger. It was modeled on Lenin who called for a revolution. Karol Wojtyła presented Lenin’s reasons: the anger of the people, social injustice, and divisions between people into the rich and the poor. Wojtyła understood this very well, and that is why he looked at the communists not as apparatchiks in a state of violence, but as people who pointed out something important. However, he ends this play with the words of Brother Albert, who, although he understands the anger of the people, “chooses greater freedom”, that is, not the path of revolution, but being with people, loving and supporting them. So the anger that communism drew from was right, but the answer it gave led to even more anger. And it was the Church, and then the “Solidarity” social movement, who understood this anger and transformed it in the spirit of love, freedom and mercy, without shedding blood.

Wojtyła believed that Catholic social teaching must answer the questions posed by the communists. And its answers must be better than those of the communists. Instead of rejecting the Marxist concept of alienation that described the experience of uprooting man from the world, Wojtyła redefined it, showing that even when we all had equal access to the means of production, alienation would not disappear. Because alienation is spiritual and only Christ can answer it. We see it today, when in affluent societies, the confusion of man only increases. This is a paradox described by sociologists: on the material level, we can have everything, but we will still not be happy. Karol Wojtyła thus restored the spiritual depth to the notion of alienation and returned to Hegel, from whom the Marxists took this concept.

Another example of this strategy was the redefinition of the concept of solidarity. This concept of the European left was introduced after the French revolution against Christian love (caritas), which from the revolutionaries’ point of view was too passive and idealistic and could not lead people to the barricades. Solidarity was supposed to do this. The communists drew on this tradition when speaking of the solidarity of their brother nations. In his most important work, “A Person and an Action”, Karol Wojtyła adopted the concept of solidarity and combined it again with love. Thus, solidarity became an authentic attitude, a correct response to an inauthentic system, to the absolutism of the state and the individualism of society. Thanks to this, John Paul II could become the spiritual leader of “Solidarity”, which aimed at preventing people from being spiritually alienated, and placed the image of Merciful Jesus on one of the gates of the Gdańsk Shipyard.

To what extent was the perspective of a pope from the communist bloc countries understandable in the Vatican?

The history of the world can be viewed through the prism of the rivalry between the papacy and the empire. In the 19th and 20th centuries, this conflict was won by empires. They showed that they were handing out cards because the popes had no division, as Stalin put it. Christianity on the international level was crushed. Due to the strength of the USSR, the Eastern policy of the Vatican was conciliatory, which greatly irritated those who lived in the Eastern bloc. Cardinal Wyszyński could not find partners in the Vatican who would understand that it was not only possible to use dialogue with communists, but sometimes to say “non possumus”. A very drastic example of communism winning this battle was that the evil of communism was not mentioned at the Second Vatican Council.

It all changed with John Paul II who made the papacy, after centuries of weakness, a global player who could challenge the empire. Before Ronald Reagan came on the scene, John Paul II began star wars and the final battle against the evil empire.

We all remember the gesture of homage in 1978, when Cardinal Wyszyński knelt down, paying tribute to John Paul II, and the Pope tried to pick him up and kneel before the primate. But we no longer remember that the same gesture was made by John Paul II in front of Cardinal Josyf Slipyj. And if the pope kneels before a former prisoner of the Gulags and the leader of the Greek Catholic Church, this shows the role of this Church and that there would be no more attempts to come to terms with Soviet Russia and eliminate Greek Catholicism.

How do you assess the role of John Paul II in the overthrow of communism?

I will not be able to answer as precisely as Lech Wałęsa, who said that the victory over communism is 50 percent of John Paul II, 30 percent – “Solidarity” (including Walesa, of course), and 20 percent – everything else. I believe there is something to these calculations. It is certain that without John Paul II there would be no “Solidarity”, the communist system would not be delegitimized on a global scale, and Reagan would not have had a partner with such a high moral capital, and at the same time understood the perspective of the Eastern bloc and the global perspective. Even if communism did collapse, it would be in a completely different way, perhaps in the midst of bloodshed, or perhaps after decades of slow decay, society would slowly lose its subjectivity, hope and faith. Then the broken, scattered Poles, deprived of spiritual leadership, would not be able to defend themselves against the more difficult challenge that John Paul II was preparing them for, and would immediately move from blatant communist totalitarianism to camouflaged democratic totalitarianism.

We were lucky that John Paul II unexpectedly appeared and that for several decades he passed on to us a universal anthropology rooted in Christianity.

Interviewer: Anna Kruszyńska (PAP)