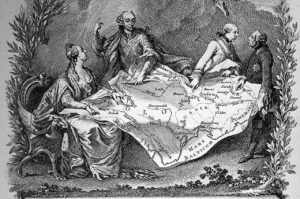

The 18th century was a time of enormous cultural, political and societal upheaval for the West. In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, it was a period of decline that was completed by the partitions. However, reducing the 18th-century history of the Polish-Lithuanian state to a mere falling into political non-existence would be a simplified and thus false endeavour. For, at the same time, it was a period that saw the state evolve until it was ready for legislative and national reform.

by Michał Rzeczycki

From a political point of view, the 18th century began for the Commonwealth with a crisis and ended with a catastrophe. However, although this age began in intellectual stagnation, it was crowned with a spiritual and educational transformation, the effects of which affected almost all the inhabitants of the country. In 1795, the state was no more, and the road to becoming a modern nation was still long. Yet, without the modernization process during the 18th century, this transformation might not have been possible at all.

This is how professor at the University of London Richard Butterwick-Pawlikowski presents the history of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in his latest monograph “The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, 1733–1795: Light and Flame.” This is not his first work devoted to the history of the Polish-Lithuanian state during the Enlightenment. Butterwick already made himself well-known as the author of “The Polish Revolution and the Catholic Church, 1788–1792”, which received extremely favorable reviews. Now, the reader receives a cross-sectional monograph from this British historian, the formal framework of which is determined on the one hand by the death of Augustus II, and on the other by the Third Partition of Poland, which put an end to the political existence of the state.

In 1733, the Polish-Lithuanian state was already in crisis. Thies clauses is explained by the author in an extensive introduction, which allows a reader unfamiliar with the history to understand the reasons for Poland’s weakness in the 18th century. The crisis had many causes. The political breakthrough took place in 1652, when MP Władysław Siciński opposed the prolongation of the Sejm debates beyond the usual six Sundays. Marshal Andrzej Maksymilian Fredro decided then that Siciński’s protest should be taken into account. As a result, the Sejm split up without adopting any resolutions. It had happened before that the members of the Sejm returned home without enacting any new laws, but it was the first time that the Sejm had been suspended by a single deputy. This is how the liberum veto began, although it is debatable whether Siciński used it in the form we know from the history of the 18th-century Polish Republic. The Sejm was formally over, and the disagreement of the Chamber of Deputies over the prolongation of the Sejm was not unusual. Nevertheless, Siciński’s gesture and the legal interpretation of Marshal Fredro initiated a free fall, which in following years would lead to the paralysis of the central legislative body. In 1669, the Sejm was suspended before the end of the session. In 1688, the Sejm was suspended even before the marshal was elected, which meant that the parliament was dissolved before the assembly could be approved. Moreover, the tragedy of liberum veto, which with time became liberum rumpo, began to spread over other state institutions. In the 18th century, it became common to suspend the Sejm. Under such conditions, any reform of the law became impossible, even though in the meantime the Commonwealth desperately needed them.

The wars of 1649–1667, including the occupation of most of the country by the Swedish and Russian troops, led to economic ruin. What followed, apart from armed conflicts, allowed for some reconstruction, but the fact that the Republic of Poland became entangled in the Great Northern War of 1700–1721 ended everything that had been achieved. The scale of the damage is illustrated by the numbers quoted by Butterwick. In 1650, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had a population of approximately 4.5 million. In 1717, this number had dropped to 1.8 million (cf. Butterwick, p. 68). For the country, which in 1650 had a total of about 12.5 million inhabitants, it was a drastic bloodletting.

The systemic, population, and economic crises that overlapped each other at this time caused a huge disconnect between the Republic of Poland and neighbouring Russia, Prussia and Austria. While the Polish-Lithuanian state experienced institutional paralysis, the neighbouring countries were subject to more and more centralization. These efficient and disciplined states, functioning in the spirit of Enlightenment absolutism, had a great advantage over a Republic of Poland that was plunging into political chaos.

The circumstances of the election of the next ruler after the death of Augustus II can serve as an example of how dramatic the situation of the Republic of Poland had become. Stanisław Leszczyński, legally elected king of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania at that time, had to flee Warsaw to Gdańsk for fear of the approaching Russian troops. They protected the supporters of Augustus III, who was proclaimed the new ruler. The Russians besieged Gdańsk until the end of June 1734. Stanisław Leszczyński left the town in the guise of a peasant on 27 or 28 June. The election of Augustus III from the Wettin dynasty was carried out, although it is clear that it was illegal. The result was determined by a foreign power. The situation was settled by the Sejm of 1736, which was, ironically, the only unsuspended Sejm during the reign of Augustus III, i.e. one that ended with the enactment of parliamentary constitutions (statutes).

The Republic of Poland was now completely paralyzed. The newly elected king paid little attention to Poland and Lithuania, putting the matters of Saxony above them. On his behalf, internal affairs were managed by his chief advisor, Henryk Brühl. Fortunately, due to the rivalry and disagreement between Russia, Prussia and Austria, the Commonwealth enjoyed relative peace. The country was slowly recovering economically from poverty resulting from the Great Northern War. In these circumstances of relative economic prosperity, a much more important process occurred from the point of view of future events.

From the institutional perspective, the Polish-Lithuanian state was in decline, but at the same time society itself was undergoing profound changes. The society was aware of the scale of Poland’s backwardness and the necessity of reforms. The key was the formation of new elites, as noted by Butterwick-Pawlikowski, who devotes a lot of attention [in his text] to the figure of Stanisław Konarski, depicting him as one of the main figures of intellectual revival in the Republic of Poland. Konarski came from the middle class nobility. During his studies at the Collegium Nazarenum in Rome in 1725–1729, he studied early Enlightenment thinkers such as Issac Newton and John Locke. After returning to Poland, he became involved in the preparation of the Volumina Legum – a collection of all the laws and constitutions of the Kingdom of Poland and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This prepared him for the main intellectual task of “disarming” the liberum veto and the ideology that justified it. He began the end of suspending the Sejm in his work “On the Effective Council”, in which he drew attention to systemic conditions in governing the state. The veto ideology was based on faith in the virtue of a single citizen who could, by breaking the Sejm, save individuals from the tyranny of the community. Konarski reversed this notion. Good government is not based on civic virtue, but on a proper system of parliament. Without good procedures, even virtue will become useless, because its potential benefits will disappear in the chaos of chaotic disorganized parliamentary debates. After all, neither in England nor in the Netherlands were there more virtuous people than in the Commonwealth, and yet both these countries were faring much better than Poland and Lithuania.

However, it was only after years of education did this political thought gain influence with the nobility, who then constituted a political nation. That is why Konarski’s political activities were accompanied by pedagogical ones. The events of 1733–1736 were a shock for him, leading him to believe that the education of citizens was of key importance for the state. As a member of the Piarist Order, he founded the Collegium Nobilium in Warsaw in 1740–1741, which was to be a school for the future elite of the state. From then on, young boys from noble houses, instead of being educated under the supervision of their parents and according to the preferences of private teachers, were being raised according to a modern program, which included the natural sciences, the Polish language versus solely studying Latin, and physical exercises. The Collegium included in its curriculum books ideas that were officially condemned by the Catholic Church at that time, such as a work by Copernicus (“On the revolutions of heavenly spheres” was included on the Index of Forbidden Books until 1819). There were other institutions established in the same character as the one established by Konarski. Earlier in 1737, a similar school was established by Theatines in Warsaw. Nevertheless, the Collegium Nobilium quickly gained great recognition, and the Jesuits, who had three times more schools in the Commonwealth than the Piarists, followed the new model. Over the next two decades, the number of elite colleges for the nobility in the Commonwealth reached a dozen. It is thanks to these institutions that the spirit of the Enlightenment blossomed and the change in the mentality took place. Without them, there would have been no reforms of the Four-Year Sejm. Neither would there have been the Constitution of 3 May.

The election of Stanisław August Poniatowski in September 1764 was entirely dictated by Tsarina Catherine II. Her intention was that the new king should be a weak candidate, without great fortune, and deprived of broader political support, and thus susceptible to Russian influence. It quickly turned out that her calculations were overestimated. Stanisław August Poniatowski believed in the reform of the Commonwealth. What’s more, he was even impatient in his belief, which often led him to years-long disputes with the Czartoryski family to which he belonged. Poniatowski also believed that he could convince the tsarina herself about the reforms, and that she would recognize the younger partner of the Russian Empire in the enlightened Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

It started out fine. During the first two years, the judiciary was reformed and the qualifications, responsibilities and number of judges and officials were established. Finally, tribunals ceased to be arenas for battles between noble parties, and became places where one could go for justice. The royal property was inspected, which significantly increased the quarter paid by the starosta (administrator of the royal territories). Above all, however, Poniatowski undertook a financial reform, and reviewed the customs and poll tax paid by Jews. The results were amazing. The annual income of the Commonwealth increased from 8.5 million zloty to 13 million zloty. But later things became worse.

As Butterwick writes, “in 1766 the royal dream ship crashed against the rock of reality” (Butterwick, p. 95). After Stanisław was elected, the Tsaritsa turned her attention to Sweden and focused on guaranteeing Russian domination there. However, when Stanisław asked her to mediate in the dispute with Prussia over customs duties, Catherine II again became involved in Polish-Lithuanian matters. The Prussians, resistant to the tax reforms in the Commonwealth, wanted to crush the Vistula trade. The Tsarina supported King Stanisław, but she did so primarily because Frederick II was flirting with the Ottoman Empire. The customs issue also irritated Catherine II. In the end, she grew furious with the rights of religious minorities in the Commonwealth.

The Extraordinary Sejm was called on 5 October 1767. The Russian demands were precise: the dissident nobility were to receive civil rights equivalent to the Catholics. In order to make sure that the wishes of the tsarina were satisfied, the Russian ambassador, Nikolai Repnin, decided to threaten the members of Sejm with violence. On the night of 13-14 October 1767, tsarist troops arrested Bishop of Krakow Kajetan Sołtyk, Bishop of Kiev Józef Andrzej Załuski, and the field hetman Wacław Rzewuski. All three – – – each of them was a senator of the Commonwealth! – – – were sent as prisoners to Kaluga. The threat worked. The Confederate Sejm, where decisions were taken by a majority of votes, reached a conclusion on 5 March 1768 and fulfilled all the demands of the Empress.

The Russian tutelage over the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the insolence of Repnin’s actions during the 1767-1768 Sejm must have provoked a reaction. A year later, the Bar Confederation was established, which some modern historians, such as Professor Zofia Zielińska, see as the first Polish national uprising. This four-year epic, although its initiators were driven by patriotism, was not free from controversy. The unsuccessful attempt to kidnap King Stanisław on 3 November 1771, provided an excellent excuse for the opposition and Russian propaganda. In the end, the confederation was suppressed and the Commonwealth paid a high price for four years of political turmoil. In 1772, the first partition took place, as a result of which Poland and Lithuania lost 4.5 million people and 211,000 km2. Previously, attempts at reform were extremely difficult due to the external and internal situation of the state. It was even more difficult after the partitions.

Title: Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, 1733–1795: Light and Flame

Publisher: Yale University Press

Butterwick’s account of the last decades of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth builds a tension between two variables: the growing awareness that reforms were necessary and the diminishing time for their implementation. The Grand Sejm is the best example of this. The four-year “window” of opportunity was opened thanks to the war between Russia and Turkey. When Russia won, the tsarina was able to establish order in the Commonwealth as she pleased. Nevertheless, the Sejm of 1788–1792 turned out to be a success. A modern constitution was passed, townspeople were granted the right to participate in the Sejms, peasants were taken (at least declaratively) under protection of the government, and the augmentation of an army of 100,000 was passed. As the historian Emmanuel Rostworowski, quoted by Butterwick, stated: “The Great Sejm […] included Poland in a group of states whose main constitutional problem in the 19th and 20th centuries was the social struggle for universal suffrage” (Butterwick, p. 300).

Richard Butterwick’s book presents the multifacetedness of the years 1733–1795 in a cross-sectional way. The author discussed the most important areas of the functioning of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at that time: external and internal relations, economic and religious problems, and personal relations between the main political actors. The language is visual, and keeps a balance between the facts of the chronicle and the rich vocabulary of belles-lettres. We are kept assured that Butterwick is a supporter of the 18th-century struggle for the reform of the Commonwealth, which ultimately took place. And although the benefits of the Four-Year Sejm were quickly lost by the Russian invasion of 1792, and the state would eventually disappear from the map three years later, the society had already been changed.

Author: Michał Rzeczycki

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin