The ordeal of Polish Army officers, policemen, prison and forest guards, intelligence and counter-intelligence agents as well as Polish administrative staff in the Easter Borderlands began on 17 September 1939. It was then that the Red Army invaded Poland, belatedly implementing the arrangements of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 23 August 1939. Soviet captivity awaited around a quarter of a million soldiers, including 10,000 officers, who were placed in several detention facilities.

by Tadeusz Wolsza

They were subsequently moved to three camps located in Kozelsk (soldiers), Ostashkov (policemen) and Starobelsk (soldiers and other servicemen). On 5 March 1940, the authorities of the Soviet Union took a decision concerning the detained Poles. The elite group of dignitaries comprising Joseph Stalin, Kliment Voroshilov, Vyacheslav Molotov and Anastas Mikoyan received a document from Lavrientiy Beria, in which the people’s commissar in charge of internal affairs of the USSR underlined that the Polish detainees were obstinate enemies of the Soviet Union with no hope of any improvement in that regard. The sentence was easy to predict: the capital punishment. The document was also signed by Mikhail Kalinin and Lazar Kaganovich. They were never punished.

Death transports from the three camps to the execution sites started in the night of 3/4 April and on 5 April 1940 (Starobelsk). Before departure, the captives received some food to take with them. At the same time, the Soviets were spreading rumours that the Poles might be free soon or begin military service in France or England. That served mainly to diffuse the tension.

The travel took between several and a dozen or so hours. First executions took place on 4 April in the afternoon. The Poles were murdered in Smolensk, Katyn, Kharkiv and Tver, and buried secretly, the content of their pockets included, in nameless graves in Bykivnia, Katyn, Mednoye and Piatykhatky. It is for a purpose that I mention the fact that the murdered were buried with the content of their pockets as three years later it was exactly documents found there and then that made it easier to identify the victims, but also to suggest the precise execution date.

Murderers from the NKVD killed 21,857 persons (although the initial Soviet plan envisaged circa 25,700 victims, including 14,700 officers). At individual murder sites, the daily rate of execution – performed by shooting at the back of the head, was between 250 and 300 persons. The killing procedure involved 125 NKVD functionaries, never tried. Nikita Petrov of the organisation Memorial identified their names on the basis of a list of the entrants for an award for their participation in a special operation in April 1940. Particularly one murderer came down in history, Vasily Blokhin, who participated in executions of police officers in Tver. He was arguably the greatest murderer in the history of the NKVD. He killed between 10,000 and 15,000 people, including his own superiors, such as Genrikh Yagoda and Nikolai Yezhov.

Only 394 captives survived the genocide, whom the Soviets moved to camps in Pawlishtchev Bor and then Gryazovets. The reasons for their survival differed. Several dozen of them, including LT Gen Zygmunt Berling and LT Gen Leon Bukojemski, decided to cooperate with the NKVD. A dozen or so others were searched by the authorities of Germany or some other countries (like Italy), using Germany as an intermediary. One such example was Cavalry Captain Józef Czapski. There was a circle of the indefatigable who did not cooperate with the Soviets but whom the latter sought themselves seeing their utility at some later stage. There were several dozen of those, the most characteristic example being that of Col. Stanisław Swianiewicz, before the war a professor of the Stephen Báthory University in Vilnius, specialising in German and Soviet economies and economics. On the other hand, one wonders why so many other professors, medical doctors and engineers detained at Kozelsk, Ostashkov and Starobelsk lost their lives despite their exquisite scientific achievements. That pertained, for instance, to specialists from the Armament Technology Institute, the Antigas Institute, the Military Geographical Institute or the Sanitary Training Centre, several hundred physicians and pharmacists as well as lawyers. A symbolic figure among the victims is Col. Józef Marcinkiewicz, a genius mathematician, recognisable in the world, a holder of a bursary in Paris granted by the Polish ministry of science and as of 1939 a professor at the University of Poznań (publishing his works in English and French). He was murdered in Katyn.

***

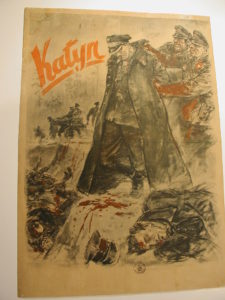

Before the spring of 1943, Polish authorities had been looking for their lost officers in vain. Most of such initiatives were carried out by Prime Minister Gen. Władysław Sikorski and the commander of the Polish Armed Forces in the USSR Gen. Władysław Anders (and on his behalf, inter alia, Capt. Józef Czapski). In April 1943, the German propaganda came up with the notion of the discovery of graves of Polish officers near Smolensk. Certain of their own innocence, the Germans went on to conduct the largest wartime propaganda operation. On 13 April 1943, Joseph Goebbels wrote the following words: ‘The Führer has allowed us now to send a dramatic report to the German press. We will be able to exploit it for several weeks.’ There existed no obstacles any more to continuing propaganda efforts using documentary films (several were produced, targeting, for instance, German audiences titled Im Wald von Katyn as well as viewers in the General Government and the Reichsgau Wartheland featuring a Polish soundtrack; and for the French showing a visit to Katyn by the well-known writer Robert Brasillach), film chronicles, radio programmes, press publications and brochures (in the General Government, the circulation of the propaganda press reached 1.3 million copies) as well as gramophone records. The Germans assigned a special role to execution site trips, made by around 31,000 people from entire German-occupied Europe, neutral countries and Wehrmacht soldiers. The Germans also brought there more than 60 Poles from the General Government and the Reichsgau Wartheland.

An important role in the process of establishing the circumstances of the crime was played by the medical commissions: a German one, an international one and one of the Polish Red Cross (led by Dr Marian Wodziński). It was the members of the International Medical Commission, including specialists from: Belgium, Bulgaria, Demark, Finland, the Netherlands, the Independent State of Croatia, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Romania, Slovakia, Switzerland, Hungary and Italy (physicians from Spain, Portugal, Sweden and Turkey supposed to arrive did not, while only an sanitary officer from Vichy managed to come from France) ascertained beyond doubt that the crime was perpetrated by the Soviets in the spring of 1940. The most prominent role among the physicians was that of Dr Ferenc Orsós, who – on the basis of prior findings of the early 1920s made in Hungary (communist crimes in the period of the Hungarian Soviet Republic) as well as studies in Katyn and Vinnytsia – made an important scientific discovery related to the date of the execution using for that purpose residues left on the victims’ mortal remains. His conclusion was accepted by the other members of the International Medical Commission, who signed the final document. The members of the Technical Commission of the Polish Red, in turn, distinguished themselves in the process of identifying the victims of the Katyn massacre and collecting artefacts retrieved from the grave pits. After two visits to the site of the Soviet crime, Władysław Kawecki, a journalist from the agit publication Goniec Krakowski, drafted the first list of names of the identified Polish officers. Once back home, other participants of trips to Katyn, having access to photographic equipment, name lists of the victims and keepsakes retrieved from the graves, such as buttons, shoulder marks and even ropes used to tie the hands of the murdered, engaged in a propaganda mission. They would prepare exhibitions, take part in milieu meetings, gave interviews to ‘prop rags’ as well as were encouraged to speak before screenings of the documentary film premiered in the General Government as early as April 1940.

The German propaganda had a clear purpose: to break up the Alliance between the Allies – the English/Americans and the Soviets (one of the articles published in the Third Reich and German-occupied countries had a title leaving no doubt for illusions: ‘These are allies of Roosevelt and Churchill. A murder of 12,000 Polish officers by the State Political Directorate GPU’, and yet another title was ‘How long will England be silent about the mass murder in Katyn?’). On that matter, the propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels wrote: ‘Everybody suspects our propaganda of spreading the notion of Katyn so much in order to bring about a separatist peace either with the English or with the Soviets. This is, obviously, not our intention, although such a possibility would be very pleasant indeed.’

Ultimately, the plan of the German propaganda was not successful. The English and the Americans backed the Soviets for military reasons (Poland’s military capacity had been already exhausted while Stalin was still able to engage thousands of new soldiers). However, they sacrificed the Polish government-in-exile and the entire Polish nation. On 25 April 1943, the Soviet Union severed diplomatic ties with Gen. Sikorski’s government. That could be seen as the beginning of the Katyn lie, the scale of which was upped by the Soviets in January 1944 after the presentation of the falsified findings of Nikolay Burdenko’s commission. The efforts of the Polish communists to send Poland’s representatives (Wanda Wasilewska and Bolesław Drobner) to the body were not accepted by Soviet authorities. Wojciech Materski has found out that it was Joseph Stalin himself who erased the names of suggested communist politicians. In January 1944, in turn, the murder site was visited by Jerzy Borejsza, as part of a larger delegation of Moscow-accredited journalists. On that trip, the participants were accompanied by a film crew that recorded the work of the commission led by Gen. Nikolay Burdenko as well as a site visit made by journalists. In January 1944, also soldiers serving under Gen. Zygmunt Berling came here. Just like the Germans in 1943, the Soviets organised a series of trips to the site of the murder they ascribed to the Germans. That initiative was on a much smaller scale than the German one in 1943. The trip to the site by Gen. Zygmunt Berling’s soldiers was obviously a vital part of propaganda activity and it inspired a documentary film with a clear message that the crime had been perpetrated by the Germans in the autumn of 1941.

Obviously, the stance of the English/Americans concerning the Katyn lie did not change. Not only did they not question the document drafted in Moscow, but they were additionally exerting increasing pressure on Polish authorities to accept the Soviet point of view. The response of Stanisław Mikołajczyk’s government was easy to predict: the Poles did not accept the Soviet arguments. Regrettably, no-one took seriously the protests from ‘Polish London’ at that stage.

***

In 1946, for the first time ever, the crime committed on Polish officers had been called genocide. That was on the initiative of Soviet prosecutors at a sitting of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, who decided to accuse the German of the Katyn massacre. As said before, they had defined the execution date as the autumn of 1941. On the basis of documents provided by Polish authorities from London as well as German lawyers, the English/Americans questioned the reliability of the witnesses selected by the Kremlin and rejected the Soviet interpretation. The event in Nuremberg was a clear signal for Polish émigré circles, and important one given their large-scale scientific, educational and dissemination activity concerning Katyn. Its main organisers were the Polish Association of Former Soviet Political Prisoners in Great Britain and the Association of Polish War Veterans. The action was actively supported by former commanders of the Polish Armed Forces in the West, including Gen. Władysław Anders, the guardian angel of Polish political émigrés.

The engagement of the abovementioned organisations manifested itself through other initiatives including articles, brochures, interviews and a 1953 documentary film. Of most importance, however, was a book titled The Crime of Katyn: Facts and Documents with a foreword by Gen. Władysław Anders, its first edition published in 1948. Both the documentary and the book were issued in several language versions (English, French, Spanish and Italian and others).

In the early 1950s, the Katyn massacre was finally dealt with by the Americans. First and foremost, they abandoned their negation of the Soviet responsibility for the gruesome events. Unexpectedly, a report was found in Washington by LT Gen John van Vliet, who as a prisoner of war visited the murder site in 1943 and in the said document stressed that Polish officers were killed by Soviets. 1952 saw the completion of work by the Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation and Study of the Facts, Evidence, and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, better known as Ray Madden’s Committee. The Americans heard a total of 81 witnesses and took testimonies from around another 200. Furthermore, they collected around 100 written declarations and accounts as well as examined 183 pieces of material evidence. The key group of witnesses were obviously Poles (including inmates of Kozelsk, Ostashkov and Starobelsk), who were heard in such locations as Chicago, London, Paris and Frankfurt. On the basis of that impressive documentation, the members of the committee ascertained that the murder had been committed by the Soviets in the spring of 1940. The Soviet Union’s response to the outcome of the work of the Madden Committee was easy to predict. The Kremlin was quick to conclude that since 1944 it had consistently claimed that the massacre had been committed by the Germans while the Americans and the English had never questioned such a finding, despite the eight-year period they had had to do so. It is also worth noting that in the USA an article titled ‘Who Is of the Katyn Massacre?’ was published in the popular periodical Reader’s Digest in 1952. Making a comment on it, Gen. Władysław Anders stressed that it was the fulfilment of the demands expressed by the Polish émigré community for many years related to the internationalisation of the Katyn massacre. He was also glad to see the Madden Committee’s initiative of arousing the UN’s interest in the matter. On 22 April 1956, a large Katyn-related demonstration took place in the British capital. Around 20,000 people took part, with the march opened by Gen. Władysław Anders holding a wreath from the Polish nation. Behind him, in silence, marched: ‘(…) generals and soldiers wearing their combat distinctions on civilian clothes, Polish miners from Welsh mines, Polish students at Oxford, […] the Home Army, paratroopers, aviators, grenadiers […].’ The Poles protested against a London visit of the Soviet dignitaries Nikita Kchrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin, consistently perpetuating the Katyn lie.

In Sovietised Poland, the Katyn trial prepared by a team of prosecutors headed by Dr Roman Martini did not materialise in 1945–1946. As the communists realised that they stood no chance of proving the German responsibility for the 1940 murder, they decided to make the whole thing go away. Yet the Katyn lie was fought against by the families of the murdered (e.g. on the radio Wave 49 putting difficult questions to the journalists), who risked repressions for their efforts as the price for telling the truth about Katyn was a prison sentence. Only until 1956, not fewer than 65 people were given imprisonment sentences for that reason, the harshest punishment being nine-year incarceration for Czesław Maciejewski from Jarocin.

The year 1990 marked a breakthrough in the history of the Katyn lie. On 13 April 1990, now recognised as The World’s Day of Remembrance for Victims of Katyn Massacre, Mikhail Gorbachev handed a package of documents proving the NKVD’s responsibility for the Katyn massacre over to Poland. At the same time, the Russian administration began a propaganda action known as Anti-Katyn.

Author: Tadeusz Wolsza – historian and political scientist, professor of the humanities and an employee of the Institute of History of the Polish Academy of Sciences. Since 2008, he has been conducting research concerning the Katyn massacre and the stance concerning it taken by journalists in the Polish People’s Republic. For several years now, he has been editor-in-chief of the journal titled Dzieje Najnowsze. Prof. Wolsza’s scientific output includes circa 200 publications (including eleven books), mainly studies and articles as well as reviews concerning the period of 1939–1989.