What is most shocking about the activities of the Ładoś Group is how effective they were when it came to saving thousands of people from the Nazis in spite of the circumstances in which they were operating. There were no machine guns, no one shouted “Hurry up!” and nobody sneaked past the walls after dark. The activity of the Ładoś Group is a Kafka-Musil grotesque of writing down protocols, stamping with round seals, and assigning ordinal numbers – all with the bitter smoke of the crematoria in the background.

by Wojciech Stanisławski

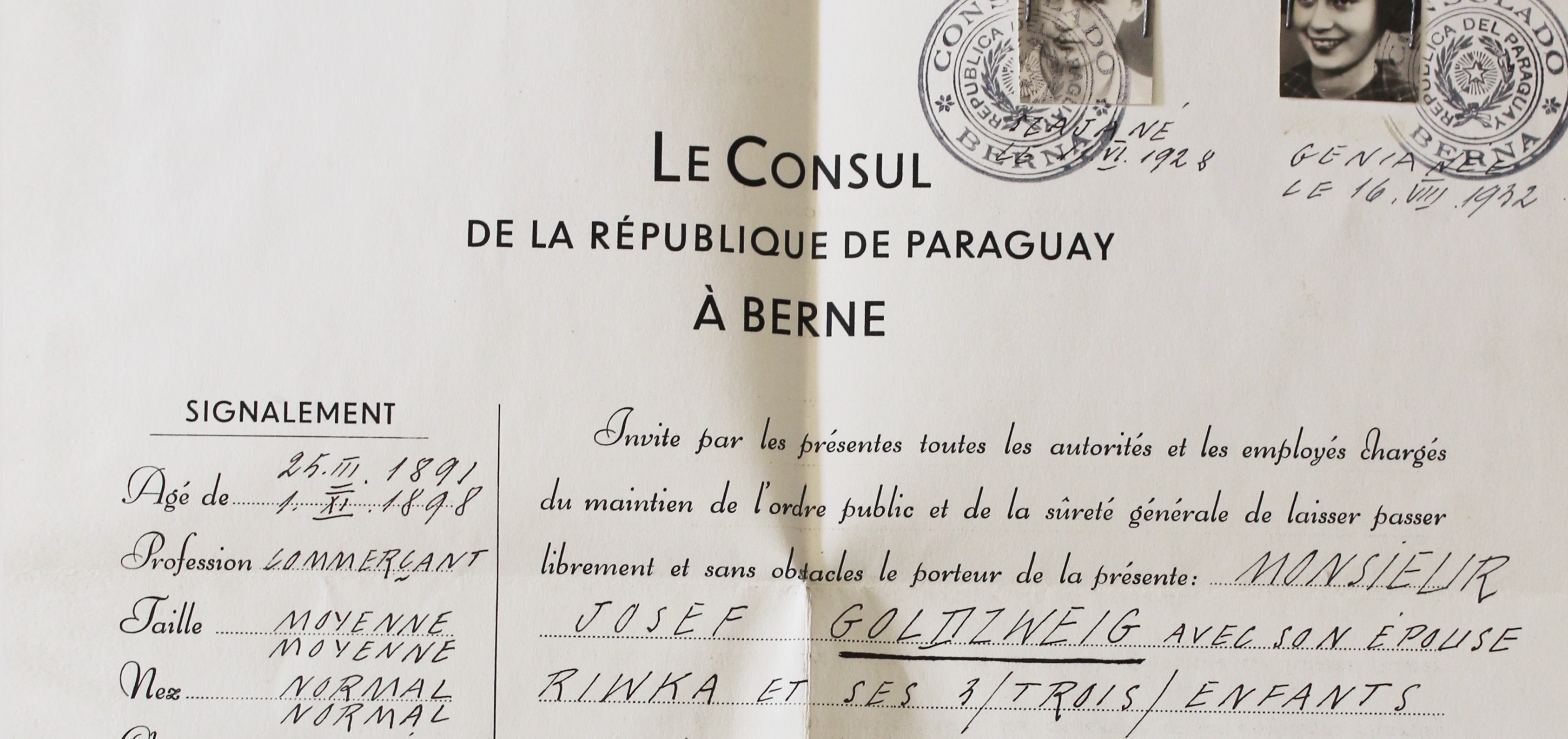

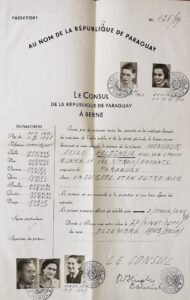

Ładoś Group is the term for a handful of Polish diplomats and activists of international Jewish organizations who organized a real “factory” in Switzerland during the Second World War that produced passports for South and Central American countries with the goal of saving Jews from the Shoah – for pre-war citizens of both Poland and other countries occupied by the Third Reich. For many years, the Ładoś Group’s activities remained virtually unknown to everyone, except for a small handful of specialists.

A pop-culture vision of the Second World War

There were many reasons for this anonymity. One of them is the small number of reports and testimonials. Also, the founders of the Group, including Minister Aleksander Ładoś, were repressed by the communists in Poland after the war and they died in poverty and oblivion or in exile. Such circumstances were not favorable for writing memoirs. Many survivors were simply unaware of the mechanism behind their salvation or did not see the need for any discussion about it. Also, few of the source documents have survived. Only today, successive “Ładoś passports” have been gradually registered in Yad Vashem archives, European archives or private collections. A considerable obstacle in popularizing the achievements of the Ładoś Group may also be the unusual nature of the entire project. It differs from the stereotypical perspectives of the Second World War in Europe perpetuated by pop culture, with black and white elections and zero-one logic: life or death, betrayal or heroism, Nazis or allies.

Title: Poselstwo RP w Bernie. Przemilczana historia [The Polish Legation in Bern. An Untold History]

Publisher: MKiDN/Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2020

The Axis countries, despite their official rhetoric prophesying the triumph and rule over the world of the Thousand-Year Reich, counted on the existence of several dozen neutral non-European countries (mainly South American) and strove to win their sympathies, or at least not to exacerbate any disputes. This assumption applied even more to neutral European countries – with Switzerland in the first place. It added extraordinary complexity to international relations in Europe: the Third Reich had to take into account (to a limited extent) the interests, sovereignty and prestige of allied states, but – even more so – the neutral states. This meant the existence, despite total war, of a dense and non-transparent network of diplomatic and consular representations, a circulation of passports of various countries and visas granted (or not), and the gradation of formal statuses of citizens in different countries, various types of citizenship, asylum or permanent stay. What if we add the fact that various countries – either declaring neutrality or formal allies of the Reich – continued to recognize the governments of the countries conquered by Hitler, and therefore also their diplomatic representations? Or, even if they did not formally recognize them, tolerated and collaborated with their representatives in their territory?

Diplomats’ counterbalance

The situation was not static. Depending on the economic fluctuations and situation on the battlefronts, neutral states tightened or cooled down their relations with the Axis or the Allies. Other countries (Italy, Hungary) were occupied by German troops for some time, which radically changed the state of affairs. There were sudden changes of the front (Bulgaria), coups, and the unexpected declaration of war on the Third Reich just a few weeks before its capitulation. Thus, the image of diplomatic and consular relations changed, and in the background the situation became more dynamic due to informal pressures from politicians and military personnel, as well as by games of intelligence. Generally, despite intentions of “total war” and “carrying out actions until the opponent’s final surrender” that were declared on both sides, neither the Axis nor the Allies gave up promising negotiations thanks to ongoing diplomatic relations. One of the best illustrations of this state of affairs is the activity of Polish diplomatic and consular services. Official representation of the Polish government-in-exile operated in several dozen neutral states of the “free world”.

This multiplicity, vagueness and changeability of formal status of citizens of different countries in the territories occupied by the Third Reich and the Soviet Union created a huge field for action. Berlin, having committed to the crime of the “final solution” and proclaiming anti-Semitism, continued to, inconsistently and chimerically, respect the rights of citizens of neutral states to a limited extent – even if they were Jewish according to the racist Nuremberg laws.

These circumstances were used by the diplomats of the Second Polish Republic, active during the war from Montevideo to Ankara. Due to the political status and geographic location of Switzerland, Polish diplomat Aleksander Ładoś, from May 1940 a member of parliament in Bern with the rank of chargé d’affaires ad interim, had the greatest possibility of action – and he used it to its fullest. He took care of Polish citizens who found themselves in Switzerland during the war or who took refuge within its borders, including soldiers of the Second Rifle Division, established in late autumn 1939 in France, who were interned there. At the same time, he was involved in diplomatic talks with representatives of countries neighboring the Second Polish Republic (including Czechoslovakia and Lithuania), and informal talks with the Soviet side, all while passing on news and resources to thousands of citizens of the Second Polish Republic who had refugee status and were scattered across Europe from the Balkans to the Pyrenees.

The Ładoś game

The most important task, however, was carried out by Ładoś in close cooperation with Consul Konstanty Rokicki, Counselor Stefan Ryniewicz, Attaché Juliusz Kuchel and citizens of the Second Polish Republic and Zionist activists: Abraham Silberschein and Chaim Eiss. The goal of these six was – to define it somewhat dryly and encyclopaedically – to obtain or produce passports of third countries, and then hand them over to Polish and European Jews with the intention of saving them from the Shoah.

But what does this say about the details of the operation of the Ładoś Group? They made their debut by obtaining several dozen blank Paraguayan passports from the honorary consul of that country, notary public Rudolf Hügli, and handing them over (after filling in and stamping them) to Jews interned in Lithuania. Thanks to this, they managed to pass through the USSR to Japan. Then, however, the time also came for the passports of Peru, El Salvador, Honduras and Haiti.

They were obtained, most often by bribery, from employees of the consulates of these countries operating in Bern; with time, people also applied for them to the Polish posts in South America. The very acquisition of the passport forms was the easiest part. In the context of the ongoing war in Europe, and since Shoah in 1941, it was also necessary to obtain personal data and photos of future passport holders, smuggle them to Switzerland, make passports there, have them stamped at the appropriate consulates and then smuggle them out a second time, this time to occupied Poland or Belgium.

The complexity of these operations is difficult to imagine, even if they took place with complete freedom of action. The Ładoś Group, however, operated while enjoying a very delicate and declining status in Switzerland, as well as being subjected to official and unofficial pressure from the Third Reich and the infiltration of German intelligence. Aleksander Ładoś and Stefan Ryniewicz repeatedly intervened with the heads of the Swiss diplomatic core and the police, protecting their associates and emissaries against the actions of overzealous policemen, counterintelligence agents and border guards. The whole tangle of these activities could best be described, somewhat anachronistically, by the English term that is fashionable today when describing counter-cultural activity, as “fringe”. The Ładoś Group operated on the border of what was legal and illegal, compliant with regulations and breaking regulations with meticulous observance and bending all possible official rules. As diplomats of the Second Polish Republic, whose recognition was withdrawn by successive states under the influence of Soviet pressure, they forged identity documents of third countries, thus breaking not only their neutrality, but also the rules ordering the suspension of immigration and granting citizenship during the war.

The result? Latin American passport holders, in principle (with all possible violations of this rule by local representatives of the Gestapo, Einsatzgruppen or other Nazi officials), were to be interned until the end of the war and thus kept alive. Most of them ended up in internment camps in Bavaria or France, although the “Ładoś passports” also went to the Balkans, Hungary, occupied Belgium, Slovakia or ghettos in Poland. In 2019, a list of over 3,200 people was published who, above all doubt, were demonstrated beneficiaries of the documents produced by the Ładoś Group. It is estimated that the names of at least 5,000 holders of these passports remain unknown, and in total about 10,000 people had the chance to survive thanks to them. Six perpetrators arranged ten thousand survivors. Churchill’s words repeated endlessly: “never was so much owed by so many to so few” suits this arrangement of rescuers and survivors exceptionally well.

Their effort has not been really covered so far. For two years, on the initiative of Jakub Kumoch, the then-Polish ambassador in Bern, a large-scale archival inquiry was conducted in several countries. Attempts have also been ongoing to identify the last living witnesses of the Ładoś Group’s operation. However, this will not replace purely academic works describing all the legal, formal and political conditions in which several Polish diplomats and activists had to operate, briefly presented above. This work was undertaken by Dr. Danuta Drywa, a Polish historian, who for many years has dealt with the history of the Shoah and the resistance, managing the archive at the Stutthof Museum, and working in the former German extermination camp located in Poland. After many years of archival inquiry, she has recreated the legal framework in which the authorities of Switzerland, Poland and a number of third countries operated, showing many hitherto unknown initiatives and fields of activity of the Ładoś Group, and revealing truly sensational details of the actions taken. At the same time, she deftly addresses legal and administrative issues. Without knowing these details, it is impossible to understand the finesse required, against which the masterpieces of the “heist movie” genre pale in comparison – no matter whether we admire “The Sting” or “Inception” more.

Author: Wojciech Stanisławski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin