On Iwicka Street in the Czerniaków district of Warsaw, an unusual house was built which was distinguished by its inhabitants – writers. Among them were Mieczysława Buczkówna and Mieczysław Jastrun, the parents of the author of the book Dom pisarzy w czasach zarazy. Iwicka 8a, which was released in autumn 2020 by the Czarna Owca publishing house. Tomasz Jastrun presents a deeply personal story about his childhood home, reflecting also on the writers’ attitude to the political system in post-war Poland. It is communism that is the plague in the title of the book.

by Tomasz Siewierski

After the war, there were several houses for writers. In the house at Krupnicza 22 in Krakow artists such as Tadeusz Peiper, Sławomir Mrożek and Wisława Szymborska lived at various times. In Warsaw, another house important for writers, was also located at 6 Róż Avenue, where not only great writers (Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński, Władysław Broniewski, Antoni Słonimski) lived, but also those who knew the culture of that time (Jerzy Borejsza, Stefan Żółkiewski, Włodzimierz Sokorski). Against their background, the writers’ house at Iwicka Street has so far escaped the attention of researchers of the history of post-war culture.

Title: Dom pisarzy w czasach zarazy [House of Writers In the Time of Plague. Iwicka 8a],

Publisher: Czarna Owca, 2020

In 1946, in ruined Warsaw, Jerzy Borejsza completed the construction of a house, interrupted during the war, several kilometers away from the Warsaw Śródmieście district. It is neither a beautiful house, nor a prestigious district, the address could not be associated with the world of artists or the intelligentsia. The district was mostly dominated by workers. However, the proposal of an apartment on Iwicka Street was in no way a humiliation to the writers. Unlike Krakow or Łódź, Warsaw was one huge pile of rubble. The authorities, however, wanted the literary community not to be dispersed. And so, at the end of the 1940s, the apartments in the house in Czerniakow began to be taken over by writers and their families. Some people didn’t stay there long, others stayed for years. “The house on Iwicka in the early 1950s became an island among ruins. An artistic and communist island” – writes Jastrun, (p. 193).

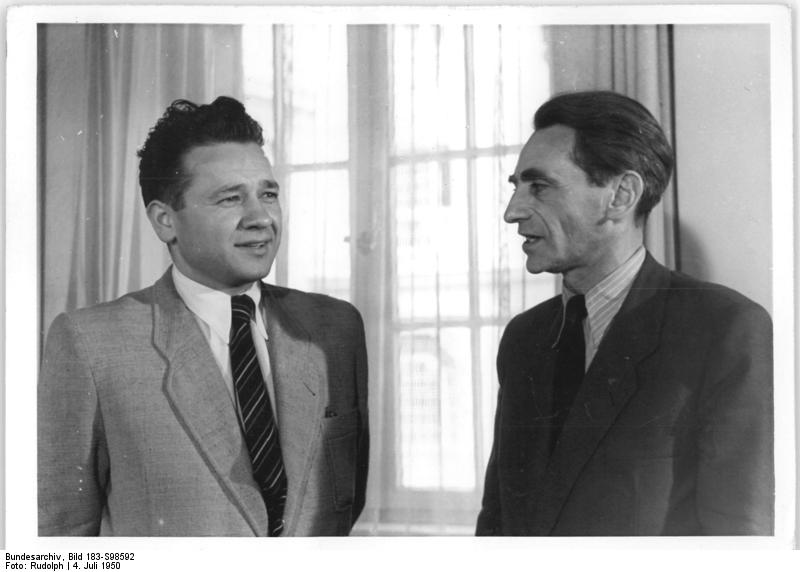

Mieczysława Buczkówna and Mieczysław Jastrun moved to Iwicka Street in 1949, and a year later their only son, Tomasz, was born. Mieczysław Jastrun died in 1983, and his wife lived here almost until the end of her life (she died in 2015). Their lives in the house on Iwicka Street are described in the form of literary collages, where chronology is not the most important aspect. Various aspects are intertwined to awaken the reader’s imagination. Unusual characters appear, including Tadeusz Borowski, Zbigniew Herbert and Julian Przyboś, but also Julia Brystygierowa. The latter, surrounded by the black legend of a sadist, headed a department in the Ministry of Public Security, which “dealt” with the artist community. She used to visit Iwicka Street, and Tomasz Jastrun describes the circumstances of her visits in a very evocative way.

Family stories are also centered around “ordinary” items, to which the author devotes a lot of attention: a typewriter, the first electric razor (made in USSR), bookshelves. There is much evidence about the author’s parents, unknown, private notes cited in abundance. The unpublished, unspoken self-criticism of Mieczysław Jastrun, written in the late 1940s, is a fascinating and awe-inspiring document. It is an excellent document illustrating the situation of writers in a country entering the Stalinist period.

Tomasz Jastrun also portrays individual tenants. However, these are not biographical entries, but rather episodes, characteristics remembered by him or his parents, often very colorful, presenting vivid portraits of famous writers. Paradoxically, one of the most interesting characters in Tomasz Jastrun’s book is Bolesław Badowski. Unlike most tenants, Badowski was not a literary man, but worked as a housekeeper. In addition, he farmed a nearby field from which some could treat themselves to tomatoes or radishes. In the yard one could meet not only pigs bred by Badowski, but also a cow and a horse.

“The house once sailed lonely like the Titanic, full of intellectual and other luxury (relatively understood luxury) on the waves of potato and tomato fields stretching to the horizon of Wilanów,” wrote one of the tenants, Bohdan Czeszko, about Iwicka. Descriptions of everyday life on Iwicka Street are a great value of the book. The privacy of great writers with their family life, wives and children, surrounding objects is fascinating. I am intrigued by the changing landscape and all the details, often overlooked, but showing the atmosphere of post-war Warsaw and Poland under communist rule. On the other hand, reflections on the writers’ attitude towards communism are disappointing. The strength lies in the author’s erudition, but he uses commonly known materials (published journals, memoirs), and does not complete the picture that we know from the works of other researchers: Konrad Rokicki or Anna Bikont and Joanna Szczęsna.

One gets the impression that the idea of writing a book about the writer’s house had been with the author since his early youth. This is evidenced by material collected several decades ago. During this time, Tomasz Jastrun supplemented it with new ideas and new questions arose. Ultimately, in The House of Writers in the Times of the Plague, the author included many topics, perhaps losing the main idea at times, because one can get the impression of a certain chaos in this narrative.

Of the nearly five hundred pages of Tomasz Jastrun’s book, one-fourth is a peculiar appendix, which are the author’s conversations with the inhabitants of the house (Juliusz Żuławski, Seweryn Pollak, Artur Sandauer) and people who often visited this house (Stanisława Przyboś, Ryszard Matuszewski, Jan Kott, Irena Szymańska). These are very valuable documents. The subject of the talks, however, is not the house at Iwicka Street, but mainly the writers’ attitude towards communism and their own entanglement in the system. These are not long conversations, but it is difficult to overestimate their value, as not all of them left memoirs. The moment of collecting these reports is also important – the last years of the existence of the People’s Republic of Poland. This “appendix” can be treated as a supplement to the book about the writers’ house, but also as a completely separate thing.

Carefully published, full of unique photos, attractively composed – Dom pisarzy w czasach zarazy (The House of Writers in the Time of the Plague) is an unputdownable book. It is full of anecdotes and diverse in content, but unequal in terms of research value. This is another important book of a documentary story not only about unusual houses, but above all about the life of intellectuals in Poland under communist rule.

Author: Tomasz Siewierski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin