There is no point in discussing Poland’s responsibility for the outbreak of World War II. Those who make this claim are fully aware of the fact that it in no way corresponds with reality. Unfortunately, this is because a lie has long served as a tool of Russian historical policy.

by Marek Kornat

Insulting accusations by the leader of a foreign country against an eminent Polish diplomat certainly deserve a historian’s commentary, although it is well known that those who raise such accusations follow political demands; they certainly do not act out of a concern for the historical truth.

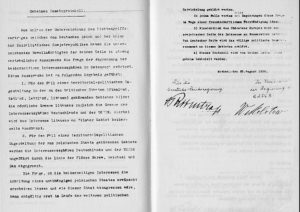

The statement about installing a Hitler monument in Warsaw comes from one document. It is a concise report by Ambassador Józef Lipski to Foreign Minister Józef Beck from 20 September 1938. Let us quote the entire document, because it is always best to let a primary source speak for itself. Especially when dealing with a controversial issue:

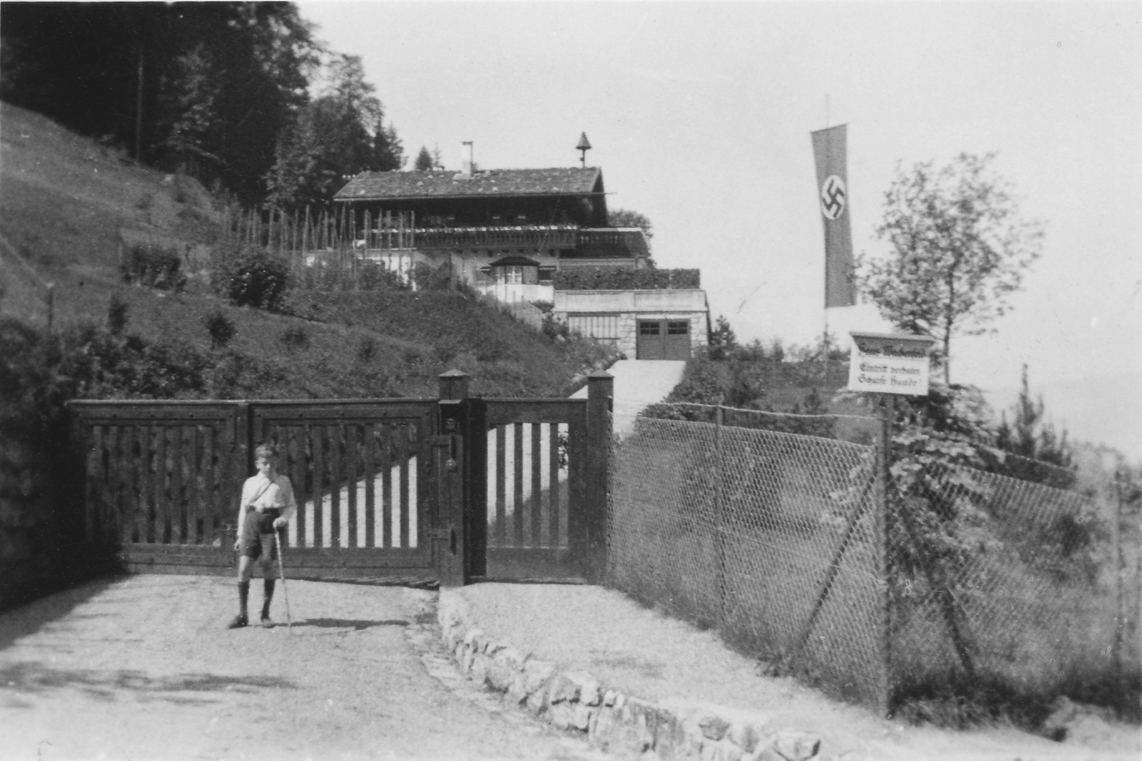

The Chancellor received me today in Obersalzberg in the presence of the Minister of Foreign Affairs von Ribbentrop at 4 pm. The conversation lasted over two hours.

The Chancellor had previously received the Prime Minister of Hungary and the Chief of Staff of the Hungarian Defence Forces.

Audiences for Poland and Hungary were granted separately. Also, while the press release regarding the reception of Prime Minister Imredy includes the merits of the issues raised, only the fact of my being received by the Chancellor is stated in the press release from my audience. We agreed on this with Minister of Foreign Affairs von Ribbentrop.

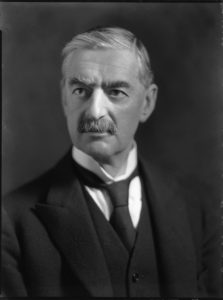

Chancellor Hitler began his conversation with me by saying that things had gone differently than he had originally thought. Then he gave an historical outline of the Sudeten case, beginning with his speech in the Reichstag in February of this year. He specifically highlighted the events of 21 May, which forced him to make a decision on 28 May regarding bringing forward the militarization and fortifications in the west. He then pointed out that he was somewhat surprised by Chamberlain’s proposal to come to Berchtesgaden. Of course, it was impossible for him not to receive the British Prime Minister. He believed Chamberlain was coming to tell him solemnly that Great Britain was ready to attack. He would, of course, then answer that Germany had considered this. The Chancellor told Chamberlain that the Sudeten case must be resolved either peacefully or by war so that the Sudeten returned to Germany. As a result of this conversation, Chamberlain, convinced of the need to disconnect the Sudeten, would return to London. The Chancellor – so far – has had no news about London’s decisions. Also, there is no definitive news as to the date of the meeting that is supposed to take place tomorrow. However, the news indicates that the Chancellor’s requests would be considered. It is true that it has been also said that the Sudeten issue should be concluded not by giving the right of self-determination to the Sudeten, but by means of establishing new borders. Apparently, where there is an 80% German majority, the territory is to be included in Reich without any plebiscite. In case of a different percentage, a plebiscite might be considered. The Chancellor has stated that he prefers a plebiscite and approves of it. He will, of course, insist on the plebiscite so that people who left the area after 1918 should be allowed to vote. The condition of 1918 must be restored. Otherwise, it would be an acceptance of the Czechization that has taken place since 1918.

Capturing Sudeten would be, according to the Chancellor, a clearer and more complete solution. Nevertheless, the Chancellor states that, regarding his own country, if his conditions are accepted, he will not be able to reject it, even if the rest of the Czechoslovak issue is not resolved. That is why the Chancellor wonders what to do in this case with the issue concerning Hungary and Poland. For this reason, he received the Hungarian Prime Minister and me for a meeting and conversation.

In reply, I stated that I would like to present Poland’s point of view in a comprehensive way. I did it in accordance with the guidelines contained in point 1-7 according to the instructions of the Minister of 19 September this year. Due to the short notice before sending this letter, I would only like to emphasize that in the Teschen case, I highlighted twice that it was an area that goes slightly beyond the districts of Cieszyn-Frysztat and that the railway to the Bohumin-Oderberg station was also important.

In the case of the Hungarian demands, I especially highlighted the issue of Subcarpathian Ruthenia, emphasizing the decisive moment regarding Russia, communist propaganda conducted in this area, etc. I had the impression that the Chancellor was particularly interested in this issue, especially when I told him that the Polish-Romanian border was relatively narrow and that the Polish-Hungarian border and Subcarpathian Ruthenia could have been a wider barrier from Russia.

I would add, that I pointed out that Subcarpathian Ruthenia is a territory to which Slovakia does not aspire, it was given only to Czechoslovakia, that the population at a very low level is strongly mixed and that actually Hungary is mostly interested in it.

When declaring our attitude regarding the Polish interest (Teschen) in the region, I pointed out:

a) that we have raised this issue with London, Paris, Rome and Berlin, and we categorically demanded a plebiscite when this option for the Sudeten was put forward,

b) that we addressed the same countries yesterday regarding the news of an alleged project of establishing borders (our declaration was submitted to Mr von Ribbentrop in writing),

c) that Poland’s position is especially strong in light of the assurance received from Prague, and confirmed by London and Paris, that our minority in Czechoslovakia will be treated equally well with other favoured minorities.

In conclusion, addressing the Chancellor’s question, I highlighted that we would not hesitate to use force in case our interests were not taken into account.

Following further analysis of the approach to be adopted in order to deal with the entire Czech-Slovak case, the Chancellor stated:

1) If his demands by Chamberlain are not accepted, then the situation is clear, and, according to his announcement, he will include Sudeten within the Reich by force.

2) If the Sudeten postulate is accepted and a guarantee is demanded from him regarding the other part of Czechoslovakia, he will assume that he can only grant it, provided that the guarantee itself will be given by Poland, Hungary and Italy. (He considers the Italian guarantee an important counterweight to the French and English ones). He understands that Poland and Hungary will not give these guarantees without taking their minority cases into consideration. I have assured about this on behalf of the Polish Government.

3) The Chancellor in response to my quite confidential message, stated that I can make good use of it, and has already answered today that in case of a conflict between Poland and Czechoslovakia over our interests in Teschen, the Reich would stand by Poland. (I think that the Chancellor had to give a similar statement to the Hungarian Prime Minister, although I was not informed about it). The Chancellor advises that we should take action only after Germany has taken over the Sudeten, because then the whole operation would be shorter.

Later on, the Chancellor strongly emphasized that Poland is the primary factor securing Europe against Russia.

Other conclusions from the Chancellor’s long arguments,

a) that he does not intend to go beyond the Sudeten area. Of course, in case of invasion he would go further, especially since I believe he would have to succumb to the military circles, which for strategic reasons would make him want the entire ethnographic Czech to be dependent on Germany.

b) that apart from certain interests of Germany, we are given carte blanche, and that he sees great difficulties in reaching a Hungarian-Romanian agreement. (I think the Chancellor may be here under the influence of Horthy’s statements, which I have verbally reported to the Minister).

c) that the cost of the Sudeten operation, including fortifications and reinforcements, reaches 18 billion marks,

d) that after handling the Sudeten issue he will raise the issue of a colony,

e) that he is guided by the idea of settling the Jewish issue by emigration to a colony, in consultation with Poland, Hungary, and possibly Romania, (on this point I told him that if he found a solution, we would install for him a beautiful monument in Warsaw).

In accordance with instructions, I discussed the issue of Polish-German relations in the above conversation. I must point out that the moment was not very appropriate, because the Chancellor was quite busy with his future conversation with Chamberlain. I raised the issue of Gdańsk, suggesting the possibility of concluding a simple Polish-German agreement stabilizing the situation of the Free City. I cited a whole range of historical and economic arguments here. In reply, the Chancellor referred to the fact that we have the 1934 agreement. He would also consider it desirable to go a step further and not only stand for the exclusion of force in our mutual relations, but to make a definitive recognition of the borders. He put forward the idea of a highway, which was already known to the Minister [Beck], connected to the railway. The width of such a highway would be – as he said – around 30 m. It would be a novelty, where the technique would be at the service of politics. He said he did not mention it now because it is an idea that can be realized later. Under these conditions, I did not go further.

Finally, at the end of the conversation, I raised the possibility – if necessary – of a quick meeting of the Minister with the Chancellor. The Chancellor welcomed this, pointing out that this could be very desirable, especially after talking to Chamberlain.

For his part, Ribbentrop asked me to ask the Minister if he would like to make a statement regarding Polish demands regarding Czechoslovakia, just as the Hungarian Prime Minister is doing, so that it could be used in talks with Chamberlain. In addition, Ribbentrop announced that in the German press our attitude regarding the minority in Czechoslovakia will be considered as extensively as possible.

I dictate the above report, before the courier leaves, after I returned by plane from Berchtesgaden. That is why I kindly ask the Minister not to mind possible errors.

*

This document has long been known to historians. It has been frequently published, including in the volume covering 1938 of “Polish Diplomatic Documents” as part of a study twelve years ago by the author of this article. What are the results of this research?

The Polish-German rapprochement – based on the agreement of January 1934 – was a reality. There is no reason to deny it. However, Poland did not have any open or secret agreement with any other country that would be directed against any third party.

The conversation in Berchtesgaden (Obersalzberg) took place when the Sudeten crisis was reaching its dramatic climax. September 1938 was marked by these events, especially the last ten days of the month. It was evident that, if left alone, Czechoslovakia would not defend itself. That France would not fulfill its ally obligations. That Great Britain, guided by an appeasement policy, would play an important part in determining the outcome of the situation. Otherwise, Józef Beck had planned a fundamental turnaround in Polish policy to avoid an alliance with Germany, because it was unthinkable that Poland would join them against its southern neighbour and the Western powers.

Let us recall that on 19 September, Beck instructed Lipski to have a discussion with the German Chancellor. The matter was of great importance. It was not about fighting against Czechoslovakia, but about a new Polish-German agreement on extending the non-aggression pact of 26 January 1934 and the stabilization agreement (as it was called by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs) pertaining to Gdańsk as a free city.

The attention during the conversation was mainly given to the Czechoslovakia issue, which is well reflected in the Leipzig report. The German leader summarised the issues related to the conflict over the Sudeten. He made a significant statement about the use of force as the best solution to occupy this territory. But in the face of concessions made by Western powers, there wasn’t any other solution left but a non-violent one, which yielded two possible alternatives: either a cession of the disputed area or a plebiscite.

In this respect, the Polish diplomat openly informed Hitler about Polish claims for Teschen, which also included Bohumin. This was an important railway junction for which, in turn, the Germans had made their claim. One can criticize Polish diplomacy, but we must remember that they acted according to the belief that the Western powers would not come to the aid of the Czechs and that the government in Prague would not choose an armed struggle if the Czechs had to fight alone. Since Czechoslovakia was to give Germany the so-called Sudetenland, why shouldn’t they also give up the small, only 862 square kilometers, Teschen region? That was the reasoning of Poland at the time.

In September 1938, no agreement was reached against Czechoslovakia. Hitler and Lipski presented their governments’ positions. Let us add that this exchange of information had been carried out by both parties since January 1938, when Hitler received Beck and let him know that Austria and Czechoslovakia would be the targets of his next expansionist moves.

A separate issue was the common Polish-Hungarian border, which was sought by the Polish government in the hope that Subcarpathian Ruthenia would be included in Hungary. Lipski tried to convince Hitler, arguing that a Polish-Hungarian border with a “relatively narrow” Polish-Romanian border would create a “broader barrier against Russia.” However, as we know, Germany was against the Polish idea of a common border with Hungary and hindered it by all available means. They were concerned about the Third Europe integration plans because they wanted to extend their own hegemony over the entire area of Intermarium.

Hitler ‘strongly emphasized that Poland was the preventive element protecting Europe against Russia’ – noted the Polish ambassador. This only means that he did not spare Lipski any compliments. But nothing came of it. The Soviet Union’s joining the war in Europe was only hypothetical. After all, war would have had to break out in the first place, and there was no sense talking about it until then.

As we can see, Lipski did not achieve anything. Hitler gave him short shrift with his (empty) promises. He threatened Poland with joining East Prussia to Germany by annexing Polish Pomerania. As a result, the Polish ambassador decided not to continue the conversation on this subject.

So where is the infamous Polish-German agreement against Czechoslovakia that Russian propaganda is discussing so extensively today?

The Jewish issue appeared in the conversation between Lipski and Hitler unexpectedly. The Polish diplomat did not plan to raise this matter. However, the German leader mentioned ‘settling the Jewish issue by forcing them to emigrate to a colony’. And in this context, Lipski’s unfortunate reference about the monument in Warsaw was made. Whatever it may sound like, such a statement – if it wasn’t indirectly ironic – corresponded with the assumptions of Polish foreign policy, which raised the issue of the emigration of Jewish people from Europe (including Poland) to Palestine and possibly to the colonial territories of European powers. At that time, other countries had adopted the same attitude and tried above all to close their borders and not let the Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria (after the Anschluss) to enter. Great Britain was blocking the influx of Jews to Palestine, which was its mandated territory. The United States did not open its borders. Special anti-Jewish legislation was passed in countries such as Germany and Italy. The language of politics and diplomacy at that time did not shun from propagating Jewish emigration as a necessary action. Moreover, the Jewish (especially American) communities themselves formulated the concepts of ‘such or other colonial postulates, possibly including the possibility of emigration for Jews’. The Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs – as Deputy Minister Jan Szembek wrote in 1938 – considered these postulates ‘desirable’.

One more thing comes to mind. How different would this conversation have been if the Polish side had expressed an a priori readiness to accept the status of an ally that was subordinate to Germany. Without consenting to this – obviously – Poland had nothing to offer its aggressive neighbour. For Warsaw, there was no option of joining the Third Reich, not even theoretically!

*

Let us emphasize that the Polish government had consistently pursued a policy of balance between Germany and the Soviet Union. Between 1932–1934, two non-aggression agreements were concluded with these neighboring powers. The fundamental premise of Polish foreign policy was the principle of not joining Germany against the Soviets and vice-versa. Such a neutrality policy between Berlin and Moscow was pursued diligently, and Poland did not change its course. The Polish state tried to adhere to its own independent foreign policy – without submitting to external forces. It was not a country passively waiting for its fate to be settled as the victim of two totalitarian powers.

Ambassador Józef Lipski was a co-creator of the policy of balance. He followed this political concept with full dedication during his six year diplomatic mission to Berlin. And it was a mission that abounded above all in German efforts to bring about an alliance with Poland against the Soviets. Polish diplomacy resisted these attempts effectively, rejecting all suggestions about adapting a common policy of both states against the Soviets and not agreeing to the Anti-Comintern Pact.

In the autumn of 1938, there was an extremely important event in Polish-German relations. As is known, Hitler made territorial claims against Czechoslovakia, demanding the Sudeten. As we also know, in May 1935, the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia concluded a mutual assistance pact. But the fulfillment of the commitments made at that time could have been completed by Moscow only via the march of the Red Army through the territory of Poland or Romania, or both. In the autumn of 1938, the Polish government categorically rejected the possibility of letting Soviet troops enter its territory. They did the same a year later – when the Soviets made such a demand against the Western powers.

Wishing to take advantage of the situation which arose in the autumn of 1938, Beck tried to bring about a new agreement with Germany on Polish terms, i.e. by extending the non-aggression pact and confirming the status of Gdańsk as a free city. There was no chance of either. However. Hitler did not need to give way in this matter because in his partitioning policy he gained everything he wanted since the Western powers were not able to abandon their short-sighted appeasement policy.

Both Germany under Hitler’s rule and the Soviet Union led by Stalin did not come to terms with the existence of an independent Poland within its Versailles and Riga borders, i.e. those that were agreed upon in 1919-1921. The non-aggression pacts were temporary, although – from the Polish point of view – quite necessary.

The Polish-German Non-Aggression Pact, concluded on 26 January 1934, was a very unpleasant surprise for the leadership of the Soviet Union. With its independent policy, Poland blocked the Soviets from entering a Central Europe that was shaping the international balance of power in the region. In the 1930s, two political plans for Central and Eastern Europe emerged. First, there was the concept of an anti-German bloc with the participation of the countries of the region and under the leadership of the USSR and the blessing of France. The draft of the Eastern Pact was the subject of diplomatic negotiations, but it collapsed because of Poland’s opposition to the terms, which – as a signatory – would have required it to let the Red Army pass through its territory in the case of an outbreak of war against Germany, as the German Reich and the Soviet Union did not have a common border. The second project was a German-Soviet agreement extending their territories. From 1933-1938, the Germans were not interested in this solution, although Soviet diplomacy attempted to bring about an economic, and then political, agreement which failed to happen. However, in the summer of 1939, the concept of dividing zones of interest in Central and Eastern Europe became a favorable option for both Germany and the USSR. This is how the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact came about. This, in turn, meant a death sentence for Poland and for a Europe consisting of free nations.

Until the conclusion of the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact, Polish-Soviet relations remained formally normalized, but in reality were full of tension and endless mutual grievances. A fierce anti-Polish campaign in the Soviet media took place at that time. This enabled the publishing of various versions of a falsified secret Polish-German agreement in the world press. One can say, without exaggeration, that it was a kind of ‘cold war’, although the term did not exist in the language of politics and diplomacy at the time. An element of this ‘cold war’ was the struggle of Soviet diplomacy against Polish foreign policy and against the German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact

Soviet accusations against Poland, insinuating that the German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact of 1934 included a secret annex, with agreements regarding the intentions of both parties against the USSR – come from the 1930s. After World War II, these accusations have become the leitmotif of a fake historical narrative about the origins of the war. They constitute a Soviet narrative to which Russian diplomacy and propaganda are now returning and they have an extensive collection of lies which they can draw on.

Author: Marek Kornat

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin