If one were to search for the distinguishing feature in Wojciech Kilar’s music among the achievements of other eminent 20th-century Polish musicians, one could point to its diversity. For Kilar was not only the author of numerous, well-known and appreciated musical film illustrations – through the prism of which he is mostly remembered today – but also of very favourably received concert hall music. Getting to know and understand Kilar’s oeuvre therefore requires taking into account both these aspects of his artistic activity. Although film soundtracks provided him with his greatest fame and income, there would have been no Kilar as the author of the soundtrack to Dracula had he not previously made a name for himself in the music world as author of the hit Riff 62, the experimental Upstairs-Downstairs, or the ecstatic Exodus.

by Iwona Lindstedt

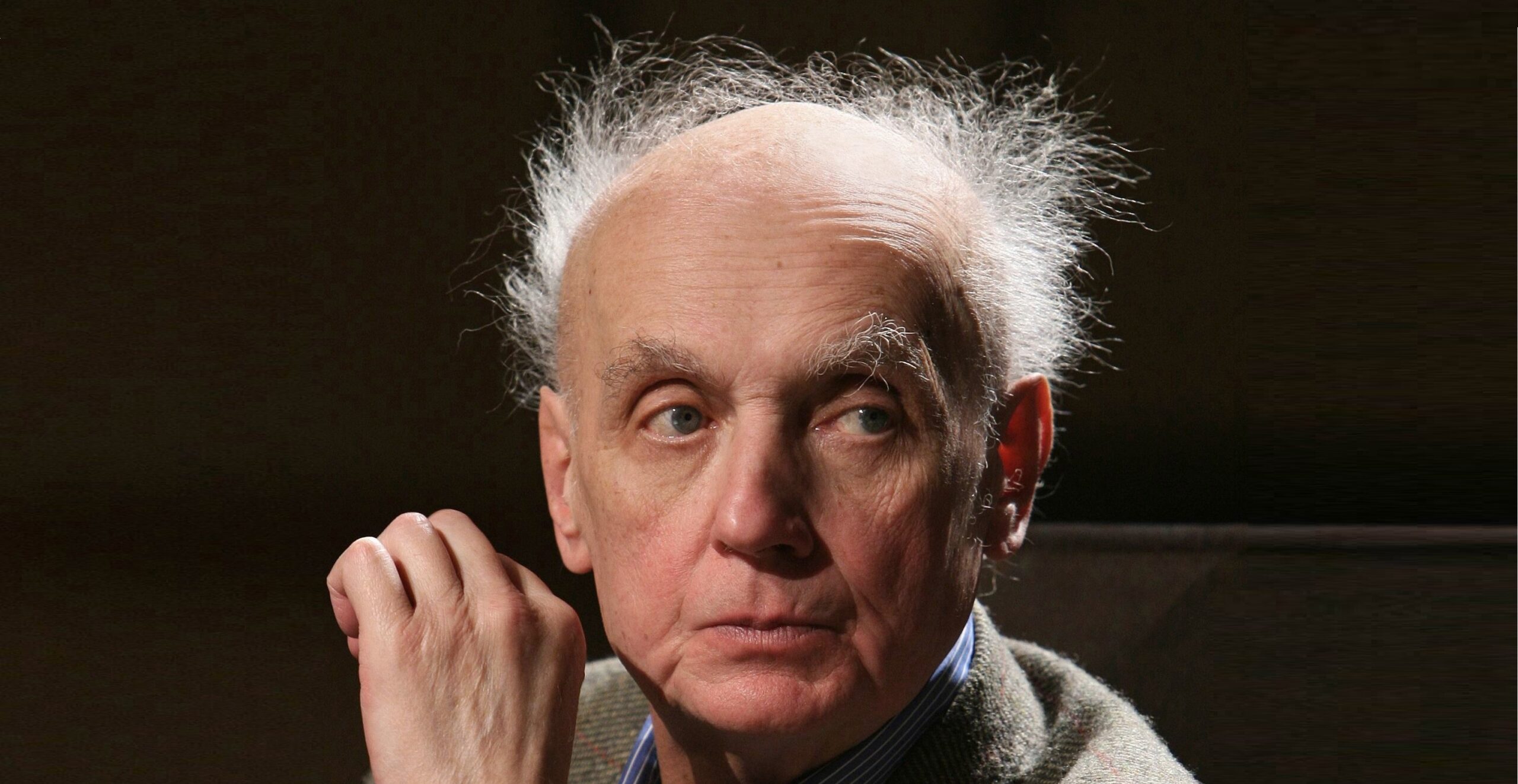

He was born on 17 July 1932 into a family in which – if only because of the profession of his mother, Neonilla Kilar (née Batik), a well-known Lwów actress – an interest in art was natural. However, little Wojtek was not keen on learning music – the tedious exercises at the keyboard bored him to death, and although he had been taking piano lessons since the age of six, there was no indication of his becoming a composer in the future. However, during his time in Lwów, just before the outbreak of the Second World War, he became fascinated by cinema – a screening of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs made a great impression on the seven-year-old. Kilar’s attitude toward learning music changed dramatically when, in 1944, as a result of the turmoil of war, the boy left Lwów with his mother and settled in Rzeszów, where he met the excellent teacher, Kazimierz Mirski. Under his tutelage, Kilar discovered the 20th-century piano repertoire and made some creative attempts, of which preserved to this day is, e.g., the piano Mazurka in E minor, written in 1946. He later continued his musical education in Kraków, in private lessons with Artur Malawski, and then at the High School of Music and the State Higher School of Music in Katowice under Bolesław Woytowicz. Living at Prof. Woytowicz’s house, he had free access to scores from his library, owing to which he became acquainted with the works of 20th-century music classics and shaped his aesthetic tastes.

Settling in Katowice was a turning point in Wojciech Kilar’s life. It was here that he found his place on earth (he referred to himself as a ‘Silesian from Lwów’) and commenced his serious career as a composer. He was soon able to boast of his success – his Little Overture was performed at the first edition of the Warsaw Autumn Festival (1956). The most important of his early works, however, was An Ode to Béla Bartók in memoriam (1957), which the composer himself called ‘his most profound piece’. In it, he encapsulated the entire range of emotions triggered by the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. The year 1957 was also a time in Kilar’s life when the young artist first came into direct contact with avant-garde tendencies in music. He attended the International Courses of New Music in Darmstadt, and the vision of new music promoted there was soon to leave its mark on his work, although he was heavily critical of it. Shortly afterwards, owing to a scholarship from the French government, he went to Paris in 1959 to study with the famous Nadia Boulanger. He then became intensively involved in the musical life of the French capital, and his ‘discovery’ of jazz music (he admired John Coltrane, Miles Davis and Ella Fitzgerald, among others) had an inspiring effect on the formulation of new goals for his own aesthetic. He decided to write music capable of captivating the listener; he simply wanted to ‘write songs’, without pretending to create masterpieces. The profile of his artistic ambitions defined in this way was perfectly reflected in his practice.

In 1962, audiences at the Warsaw Autumn Festival responded enthusiastically to his orchestral firework Riff 62, whose very title betrayed his jazz inspirations, and after that – year after year – no less interest was aroused by his subsequent avant-garde compositions:

Générique (1963), Diphthongos (1964) and Springfield Sonnet (1965). At that time, Kilar, together with the young Krzysztof Penderecki and Henryk Mikołaj Górecki, was consistently building up the reputation of the so-called Polish school of composition, creating music that primarily emphasised tone and sound, whilst simultaneously being interesting and convincing in terms of dramatic features. However, he soon realised that the possibilities of this style were rapidly running out, and, as a result, he again began to seek new solutions. He found himself in music marked by an increasing simplicity of form and economy of means of expression. The late 1960s and early 1970s thus produced works such as Training 68 (1968), Upstairs-Downstairs (1971) and Prelude and Christmas Carol (1972), which signalled that he would be consistent in his stance.

The 1970s ushered in a series of concert ‘hits’ in Kilar’s oeuvre. First came Krzesany (1974), followed by Kościelec 1909 (1976) and Siwa mgła (Grey Fog, 1979), and finally, in 1986, the hugely successful Orawa (1986) – one of the few works in which the composer – as he said himself – in retrospect ‘would not change a single note’. What all these works have in common is the original reworking of the music of the highland region of Podhale, which in the eyes of music critics made Kilar a type of heir to Karol Szymanowski. Indeed, the Podhale region was a great inspiration for Kilar – its echoes can be heard in many of his other works, and even in those of a religious character, such as Magnificat (2006). These began to increase in Kilar’s oeuvres from the mid-1970s, as the composer turned to hitherto completely unheard of genres, which is related to the change in his world view that took place during martial law (1981–1983), when he began frequent visits to the Marian sanctuary at Jasna Góra in Częstochowa. The path through Kilar’s religious output has since been marked by works such as Exodus (1981), Victoria (1983), Angelus (1984), Missa pro pace (2000), Veni Creator (2008), Te Deum (2008), as well as the more minor, more recent works for a cappella choir, such as Lament (2003), Paschal Hymn (2008) and Prayer to Little Theresa (2013).

Kilar did not abandon symphonics, however, and during the final period of his life, created two piano concertos (1997 and 2011) and three symphonies. In his September Symphony (2003), written following the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York, he referenced gospel music, American hymns, and patriotic songs. His symphony ‘about movement’ (Sinfonia de motu, 2005), written for the World Year of Physics, was based on a musical motto composed of notes whose letter symbols are identical to those of certain physical constants and concepts (c, h, G, e, a). And in the last one, Advent Symphony (2007), he included references to the musical culture of his beloved Silesia and gave expression to his deep religiousness. Most importantly, Kilar’s late music grew out of a deep conviction of the need to limit compositional means in favour of maximising expression. This clear approximation to minimalist aesthetics also had religious connotations for the Polish composer – for he noted that the repetitive nature of musical phrases corresponded perfectly with the repetitiveness characteristic of prayers, such as the rosary prayer.

It is significant that Kilar’s debut as a film composer came at a time when his ‘serious’ aesthetic goals were crystallising. For he made his debut in 1958 with music for Natalia Brzozowska’s documentary film The Skiers. Subsequent commissions followed and, from then on, he systematically created music for films – in parallel to autonomous music. This sizeable body of work includes Kilar’s collaborations with some of the most eminent directors, which include over sixty names. Some of them he met with only briefly, with others – such as Kazimierz Kutz, Krzysztof Zanussi, Andrzej Wajda, Roman Polański – one could say regularly. Works that have made a special mark on the history of Polish and world cinema include such titles as Tadeusz Konwicki’s Salto, Marek Piwowski’s The Cruise, Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Blind Chance, Krzysztof Zanussi’s A Year of the Quiet Sun, Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Jane Campion’s The Portrait of a Lady, and Roman Polański’s The Pianist.

Kilar’s film music (a total of 176 titles) – for feature films, series, animations and documentaries – appreciated both for its ‘catchy’ melodies, evocative and varied instrumentation, and perfect integration with the image, theme or mood of the film, has brought the Polish composer worldwide renown. However, Kilar himself – although he derived much satisfaction from this activity – considered the writing of film soundtracks to be a less important strand of his work. It was clear that he was doing it for a living and creating music for films that had to be adaptable to the director’s or producer’s vision of the screen. And he was able to write everything for the cinema – from a romantic waltz, through folk, jazz or avant-garde styles, to themes neatly characterising individual protagonists. He even developed his own cyclical cinematic form, which he himself called – as in relation to Dracula – an oratorio, a cantata or a vocal-instrumental suite. However, he emphasised that it was his autonomous music that influenced his applied music, not the other way around. He included concert works into the programs of his concerts, during which suites based on film themes were performed, and noted with satisfaction that, through the mediation of the ‘tenth muse’, listeners were also beginning to take an interest in his symphonic works. On the other hand, he was delighted to hear that The Ballad of the Little Knight, sung for the first time in the credits of the TV series entitled The Adventures of Sir Michael, based on the novel by Henryk Sienkiewicz), directed by Jerzy Hoffman, became the anthem of Polish volleyball fans. It was also a source of satisfaction for him that, at balls known as proms, Polish future high school graduates usually dance the Polonaise he had composed for the film Pan Tadeusz (based on the epic poem by Adam Mickiewicz), directed by Andrzej Wajda.

It could be said that both strands of Kilar’s work were guided by the same assumption – the composer wanted to write only music that people wanted to listen to. For him, sound art was above all a means of communication with the audience. There is no doubt that Wojciech Kilar’s name is recognised today mainly in the context of film music, which is not in accordance with the wishes of the composer, who wished to leave his mark mainly in completely independent music. Therefore, when listening to his soundtracks, it is worth remembering that, towards the end of his life, he did not work much for cinema, avoiding such offers as much as possible, even procrastinating about composing for his friend Krzysztof Zanussi (he did not manage to fill the score for the film Foreign Body with notes, although he assured that he had that music ‘in mind’). In the year 2012, when he celebrated his 80th birthday, he wrote Sonnets to Laura for baritone and piano, which graced the opening ceremony of the Senior Musician’s House in Kąty near Warsaw. He also received a number of awards, including the Order of the White Eagle, Poland’s highest decoration, in recognition of the great contribution his work had made to Polish culture. He died in Katowice on 29 December 2013.

Author: Prof. Iwona Lindstedt – Professor at the Institute of Musicology, University of Warsaw

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki