He witnessed the country’s turbulent history in the second half of the 18th century. This active politician, great patriot, and distinguished reformer is considered one of the fathers of the Constitution of 3 May 1791.

by Piotr Abryszeński

Stanisław Małachowski was born in Końskie, an estate that had belonged to the family for generations, on 24 August 1736. The Małachowskis appeared on the political scene only in the mid-17th century, hence relatively late. Much of the credit for this goes to the thriftiness of Jan Małachowski, Bishop of Cracow, and trusted advisor to Kings John Casimir and John III Sobieski. The grandfather of the later Speaker of the Sejm, also named Stanisław, received the hereditary title of Count, and was a Member of the Sejm negotiating the Treaty of Karlowitz, ending what is known as the Great Turkish War, which finally stopped the expansion of the Ottoman Empire in Europe.

The beginnings of young Stanisław’s political career were not the easiest. Although he had received a good education owing to competent tutors, he initially had great difficulties with public appearances. The then fashionable military training did not attract him either, so he eventually abandoned the uniform of the captain of the armoured banner. However, he perfectly understood the importance of a strong army for the state.

In 1764, he joined the powerful party of the Czartoryski confederation, and participated in the election of Stanisław August Poniatowski as King of Poland. The monarch appreciated his supporter, decorating him with several orders, which meant both appreciation of his work and support for his future activities. Małachowski’s enthusiasm soon waned, as he witnessed the interference of Prince Nikolai Repnin in Poland’s internal affairs, and the blocking of necessary reforms. The King was clearly betting on the Russians. In the circumstances, Małachowski withdrew from public life for some time.

After a few years, the King entrusted him with the mission of putting the legal system of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in order. In this role, Małachowski provided great service to the Crown Tribunal, of which he became Marshal in 1774. He curbed corruption and abuse committed by that body. Historians agree that, owing to his activity, the Tribunal regained its former respectability in society. He then became a member of the Permanent Council, the highest organ of administrative power established under the inspiration of Tsarina Catherine II. Although the Council modernised the system of state governance, it weakened monarchical power, and led to the further dependence of Poland on the growing power of Russia. Małachowski’s service to the Polish cause brought him another honour as, in 1782, he was awarded the highest state decoration, the Order of the White Eagle.

On 6 October 1788, he was unanimously elected Speaker of the Sejm, which went down in history as the Four-Year Sejm, or the Great Sejm. The choice of Małachowski was not incidental – his candidature was approved both by the royal party, which wanted to consolidate the government based on a close alliance with Russia, and by the opposition, which was against Poland’s dependence on other states. He maintained good relations with the representatives of both parties and, at the same time, did not declare himself an opponent of King Stanislaus II Augustus. Moreover, he enjoyed an impeccable reputation, and was regarded as a man of great integrity, as well as a sincere, devoted patriot.

The Sejm made an attempt to put the political situation of the Commonwealth in order, to strengthen it by means of profound reforms, and to save its independence. This was a difficult task, especially after Poland’s first partition in 1776, through the cession of some territories to three powerful neighbours: Russia, Prussia, and Austria. Małachowski himself joined the moderate wing of the Patriotic Party (together with Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj), which strove to strengthen the sovereignty of the state. He proposed, inter alia, the introduction of the hereditary throne, and the establishment of a constitutional monarchy following the English model. At the same time, he strove to conclude an agreement with the King. He was also an advocate of extending the political rights of towns, and of cooperation between the nobility and the bourgeoisie. He was known as a supporter of the enfranchisement of peasants, which he managed to carry out fully on his own estates, as well as organising medical care for them.

As early as in January 1789, the Sejm abolished the Permanent Council, which was increasingly controlled by the Russians, and which essentially became a body controlling the King. In practice, this decision meant the liquidation of the Russian protectorate, and provided an opportunity for independent reforms. The Russian army was forced to leave the territory of the Commonwealth. In September of that year, the Deputation for the Government Statute was appointed, headed by the Bishop of Kamieniec Podolski, Adam Stanisław Krasiński. It was this body that was given the task of drafting an outline for changing the political system.

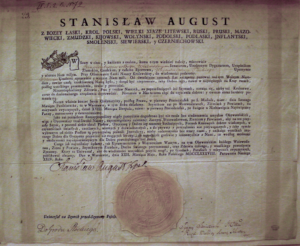

The most important work of the Four-Year Sejm, led by Stanisław Małachowski, was the adoption of the Constitution of 3 May 1791, the first modern constitution of a state in Europe. It was in his apartment in the Czapski-Raczyński Palace on Krakowskie Przedmieście in Warsaw that the text of the act was drafted, in secret from the opponents of the reforms. The Marshal pushed through the adoption of the Constitution by the Sejm, and was also one of the signatories of the Act.

The document was only in force for a year or so. Increasingly embittered by the King’s unstable attitude, Małachowski lost hope for a happy turn of events. In May 1792, part of the aristocracy, in agreement with the Russians, formed the Targowica Confederation, opposing the Constitution. This confederation is still considered a symbol of national treason. When the King joined the Targowica faction, Małachowski announced an act condemning the confederation, in which he strongly supported the Great Sejm. In it, he stated the following, inter alia: ‘Lest I feel remorse, which reminds me that the misfortune of the Commonwealth is approaching. Nation, I only sacrifice my tears and fidelity to you, when all the means in my hands have already been snatched away’.

Soon came the second partition of Poland. A response to this act was the outbreak of the Kościuszko Uprising. Małachowski, however, refused to support the insurrection, because he feared that the slogans proclaimed by its initiators were overly radical. The uprising failed and did not save Poland from the final partition, as a result of which the country disappeared from the map of Europe.

Resigned, Małachowski went into exile, but was arrested by the Austrian authorities upon his return to Cracow, and imprisoned for several months. His stay in jail brought him many supporters, and rendered him a symbol of the battle for the Polish cause. Hopes for independence were revived in the early 19th century, especially after Napoleon’s brilliant victory over Prussia. In 1807, the French Emperor established the quasi-independent Duchy of Warsaw, an ersatz sovereign Poland. The Emperor appointed the distinguished politician President of the Governing Commission, the provisional government of the Duchy. However, Małachowski opposed the introduction of laws, including the Napoleonic Code, in the Duchy. Until the end of his life, he was also a supporter of the reactivation of the Constitution of 3 May 1791, which, however, was increasingly met with incomprehension.

Stanisław Małachowski did not distinguish himself with valour on the battlefield, but his civic attitude, steadfastness, integrity, and determination to work for the benefit of the homeland, won him great recognition in the eyes of his contemporaries and posterity. He did not spare his private fortune to support the state treasury and the expansion of the army. Already during his lifetime, Małachowski’s merits were appreciated, and he was compared to the Athenian politician Aristides the Just. He died on 29 December 1809 at the age of 74.

Author: Piotr Abryszeński

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki