We all know the poem by Władysław Bełza, “The Catechism of a Polish Child,” written in 1900, and we will all reply without a second thought: the white eagle. Still, it would not come amiss to wonder: why the eagle?

by Beata Wolszczak

The legendary Lech had resolved to settle in the flatlands, where soils were good, the climate mild and lakes and rivers numerous. He called this site Gniezno (from gniazdo, or nest). In his work Roczniki czyli kroniki sławnego Królestwa Polskiego [Annales seu cronicae incliti Regni Poloniae – Annals; or the Chronicles of the Illustrious Kingdom of Poland], Jan Długosz has written: For that was where Lech, the sovereign and sire of Poles, had made camp and resolved for the first time to relinquish his life of a nomad; and to make this place a nest for himself and his elders; he decided that this is where the princely See shall be erected and where it shall remain in perpetuity. It was there that, in the high and lofty trees, he found an eagle’s nest. More than a century later, another chronicler, Marcin Bielski, added: Hence he had ordered that the white eagle be displayed on his banners as his coat of arms, and from that time onwards this gem has been used by the Kingdom of Poland. In the 17th century, Marcin Kromer confirmed that this coat of arms had been passed on by Lech to Polish kings and princes:a white eagle, elevated, its wings spread.

The legend of the establishing of the Polish national emblem is corroborated by history. The story of national symbols: the emblem, the coat of arms and the national colors, is inextricably bound up with the darker aspects of history. When groups of individuals began to fight one another, battle emblems came into existence. They helped distinguish between the warring sides, assigned assembly points, indicated the direction of attack. Ensigns served as the first battle emblems. With time, armored cavalry began to appear on the battlefield. Still, the armor worn by the warriors were very much alike, and helmets concealed the men’s heads and faces. It became impossible to tell enemies from allies. Thus banners of various colors began to be seen; adorned with a simple image, they were often attached to a spear. This enabled knights, enclosed in armor, to recognize one another on the battlefield. The colors and images began to be transferred from banners onto shields. The signs or emblems were chosen with the objective that they carry suitable symbols. They could display the virtue of the knight or his ruler; for instance, strength, courage or valor. Since time immemorial, the lion, the king of animals, and the eagle, the king of the skies, had been symbols of these characteristics. Thus the eagle (along with the lion) became one of the most popular images on coats of arms.

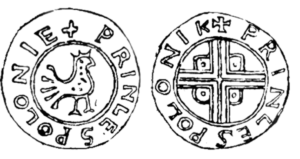

The image of the eagle first reached Polish lands on Roman coins, brought by merchants trading along the Amber Road. When it began to be used as a decorative sign or motif remains unknown. A silver dinar minted during the reign of King Bolesław Chrobry was the earliest Polish coin showing the image of an eagle. It was minted in 1000, following a meeting with Emperor Otto in Gniezno. The eagle is first mentioned in the chronicle by Wincenty Kadłubek, who claims that, during the 1182 Battle of Brest (with the Ruthenian army), King Kazimierz the Just had fought under the emblem of the victorious eagle, the symbol of regal majesty. During the feudal fragmentation of Poland, the eagle emblem was well-known and popular in the Polish lands: it was used by almost all princes of the Piast dynasty – in Silesia, Lesser and Greater Poland, as well as in Kujawy and Masovia. In late 13th century, when three princes made an attempt to unite Polish lands, they made use of that very emblem. The Dukes of Wrocław, Henryk Probus, of Greater Poland, Przemysł II, and of Kujawy, Władysław Łokietek, added majesty to the eagles on their seals by crowning them.

Poland must be the only country in Europe capable of assigning a precise date of birth to its national emblem. On 26 June 1295, following the coronation of Przemysł II, the eagle became the official emblem of the reunited Kingdom of Poland. The image of Przemysł’s eagle has survived on his royal seal, which can be seen on a document dated August 1295. Przemysł’s seal shows an imposing crowned eagle, encompassed within the Latin inscription reddidit ipse Deus victricia signa Polonis [the Almighty himself hath restored their victorious emblems to the Poles]. The crowned eagle became a symbol of the state’s sovereignty and unity.

The image of the Polish eagle has changed over the centuries. Since the time of Władysław Jagiełło’s reign, after the commonwealth with Lithuania had been established, the eagle emblem appears alongside Lithuania’s coat of arms of a mounted horseman, or Pogoń. Some kings added their dynastic coat of arms to the image of the eagle, while others displayed their monogram on the eagle’s breast.

When Poland fell under partitions, the symbol of the eagle stood for the continuity of the Polish state, a symbol of striving towards sovereignty. During the First World War, the countries that partitioned Poland used the image of the eagle with a view to garnering the support of Poles for their politics. One example is the historical drawing showing an Austrian soldier and one from Germany releasing the white eagle from its cage in 1916.

In 1917, the governor-general of Warsaw issued a decree introducing the Polish mark, which became the sole legal tender on the territory of the Kingdom of Poland, which remained under German occupation. The verso of the notes issued by the Polish National Loan Bank was adorned with a beautiful Renaissance eagle, very similar to King Sigismund eagles from the arrases of Wawel Castle. This was the first official, administrative use of the Polish national emblem since the failure of the November Uprising of 1830. On the Polish mark banknotes issued in independent Poland, the eagle appeared alongside images of Queen Jadwiga Andegaweńska or Tadeusz Kościuszko.

As a result of the partitions, Poland had lost independence; it had ceased to be a monarchy, and the crown on the White Eagle’s head lost its symbolic meaning. The crown became a subject of contention and numerous discussions among various political groups. Some (of democratic and republican provenance) rejected the crown as a symbol of the Poland of yesteryear, a Poland governed by noblemen who had modelled themselves on the Sarmatians. Thus the ensign of the Democratic Society of Poland featured an eagle without a crown; the same image was included in the symbolic repository of the Kraków Uprising of 1846. During the January Uprising, some troops were noted to fight under the emblem of a crownless eagle. Also lacking crowns were the eagles on the visored caps (maciejówki) of the riflemen of I Kompania Kadrowa as they set off to war from Kraków in 1914. While it is true that the eagles borne by that army (the Polish Legions) acquired their crown two years later, the commander-in-chief of the Legions, Józef Piłsudski, wore a crownless eagle on his cap until the end of his life.

The coat of arms of the Republic of Poland is established as a white eagle whose head is turned to the right (to the left from the vantage point of the viewer), whose wings are upraised, with claws, crown and beak golden against a red rectangular background; thus had the bill of 1 August 1919 of the emblems and colors of the Republic of Poland determine the appearance of the Polish national emblem. The official emblem of the Republic resembled the eagle of King Stanisław Poniatowski. This had been in use until 1927, when a new version was completed, designed by Zygmunt Kamiński.

In 1944, communist authorities eliminated the crown from the eagle’s head. The rather unsuccessful 1943 design by Janina Broniewska (commonly known as kurica, or the hen), had been modelled on the princely tomb of the rulers of Poland interred in Płock. This had been recognized until 1952, when the official coat of arms of the People’s Republic of Poland was published in the constitution of 22 July of that year. It was a faithful copy of Kamiński’s design, minus the crown.

The Sejm of the Republic of Poland in its tenth term (the so-called contractual Sejm) changed the constitution during its final assembly on 29 December 1989. As a result of the change, the state’s former name, the Republic of Poland, and its coat of arms, the crowned White Eagle, were reinstated.

PS: The Władysław Bełza poem “The Catechism of a Polish Child” had been subjected to censorship in 1951, and was withdrawn from libraries immediately.

Author: Beata Wolszczak

Transation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin