During his June 1979 meeting with youth in Gniezno, Pope John Paul II intoned the song ‘Red belt’. Three hundred thousand participants of the Holy Mass sang the refrain in chorus: ‘For a Hutsul, there is no life like in the highlands / when fate throws him into the pits – he soon perishes from longing.’ The Carpathian homeland of the Hutsuls, forcibly incorporated into the USSR and inaccessible to Poles for half a century, grew into their culture as strongly as Lwów and Vilnius, the capital cities lying within the Borderlands. And in some respects even stronger.

by Wiesław Chełminiak

Greeks from the Cheremosh

Pokuttia (Pokucie), whose southern border was marked by the peaks of the Gorgany and the Chornohora, was incorporated into Poland by King Casimir the Great in the mid-14th century. A poor and sparsely populated region, it was long shunned by the Great History. This changed only after the outbreak of the First World War. The strategically located village of Rafajlowa became the scene of battles between the soldiers of the 2nd Brigade of the Legions, also known as the Iron or Carpathian Brigade, and the Russians. Soldiers under the command of Józef Haller stopped the enemy’s attacks and, in record time, managed to build a road in the mountains to enable a counter-offensive. In independent Poland, the Pass of the Legions, decorated with a large cross commemorating the fallen, became a destination for patriotic excursions.

The bloody battle of Rafajlowa overlapped with the already established image of a magical land with forests, wooden churches, and moustached highlanders. The myth of the Hutsuls resembled the stereotype of the ‘noble savage’ widespread in the West. Their neighbours – the Boykos and Lemkos – never aroused such interest. The folk culture of Pokuttia, emerging from Ruthenian-Wallachian roots, became an inspiration for a multitude of writers and painters, who could repeat after the philosopher Stanisław Vincenz: ‘The Hutsul Region is my human homeland’.

Vincenz was an opponent of centralism. He resigned from his career as a civil servant in protest against the policy of ‘tightening the screws’ on national minorities. According to the official propaganda of the Second Polish Republic, the southern borderlands were not inhabited by Ukrainians, but by Carpathians loyal to the state. Delegations of Hutsuls wearing costumes were a regular feature of official celebrations. Meanwhile, Vincenz erected a boulder in his own garden, commemorating Ukrainian poet Ivan Franko, and was involved in the preservation of local architecture, costume, and landscape. He supported the idea of publishing a newspaper in the Hutsul language, and creating the National Park of the Prut and Cheremosh Valleys. An expert in Homer, he believed that the Eastern Carpathian highlanders – like the ancient Greeks – preserved the memory of the archaic civilisation. He constructed a wooden house in the village of Bystrzec, where the first volume of his opus magnum Na wysokiej połoninie (On the High Uplands) was written (the others came out in London during his emigration). The author contrasted the vision of the world of traditional values with Marxism and Darwin’s ‘struggle for existence’.

The borderlands of the Borderlands

Vincenz had a great influence on Czesław Miłosz (who called him the ‘Polish Tolkien’ and ‘the last sage of the 20th century’), but it was not he who made all things Hutsul fashionable. It began with the death of Oleksa Dovbush, the leader of a gang raiding in Pokuttia in the 1740s, a hero of folk songs and literary works. Many highlanders at that time earned their living as brigands. In the old Romanian dialect, Hutsul meant a thug. The legend of Dovbush, combined with the fascination with folklore, wild nature and theories about the ‘pre-Slavic’ virtues of Carpathian Ruthenians, seduced the Romantics. The Gorgany and the Chornohora did not provide opportunities for Tatra-style climbing, but they were ‘home mountains’ for Lwów, which, in the 19th century, became a metropolis of this part of Europe. Stanislaviv, the third largest city in Galicia, was not far away, either.

News about the land of noble brigands and amorous shepherds was spreading increasingly widely. Tourists were not disappointed: they were captivated by the colourful costumes of the villagers, decorative ceramics and woodcarving, and small horses, ideal for working in the mountains. To arrivals from central, flat Poland, these ‘borderlands of the Borderlands’ seemed both familiar and exotic.

In the basins of the Prut and Cheremosh Rivers, one could meet Hungarians, Romanians, Germans, and Jews. In the 18th century, the charismatic Baal Shem Tov – founder of the messianic Hasidic movement – meditated and taught here. The small town of Kuty, from which the region took its name of Pokuttia, was the unofficial capital of Polish Armenians. Interestingly, the religious-ethnic mosaic did not generate major conflicts. Dovbush’s countrymen had their disagreements with Jewish leaseholders and usurers, but the reason for this was money. The bloody epilogue of one such dispute inspired Stanisław Wyspiański to write his drama The Judges.

Fleas bit the suffragette

Europe discovered the Hutsul Region in 1880 owing to an ethnographic exhibition in Kolomyia. It was honoured by the visit of the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, preceded by a procession of 300 Hutsuls on horseback. It must be said that His Majesty exhibited good taste. He ordered a stove decorated with tiles by Aleksander Bachmiński for his Schönbrunn Palace. Ceramic items from Kosovo, where Bachmiński ran his family workshop, had already conquered the hearts of Lwów residents. Famous fairs were held in the town, where more and more holidaymakers bought colourful kilims, lyzhniki (woollen blankets), embroidered shirts, faience whistles, glass paintings, hand-painted plates, icons, elaborately decorated Easter eggs, and wooden sculptures.

In the summer of 1890, 23-year-old Ménie Muriel Dowie crossed the Hutsul country on horseback (and in Scottish costume). She described her impressions in the book titled A Girl in the Karpathians, which was published in five editions in a single year in London. The British suffragette was delighted with the mountains, the villagers appeared ‘simple and amusing’ to her, but she complained about the cuisine, and the state of hygiene. The traveller was bitten by fleas while staying at a Hutsul hut. The readers especially enjoyed the chilling description of rafting on the troubled Cheremosh River.

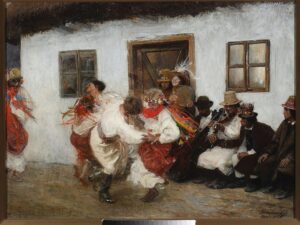

The wildness of Pokuttia was already quite questionable at that time. The oil fever, plundering forestry, and growing tourism were changing the face of the region. Artists seemed not to notice this, however. Hutsul motifs were used by renowned painters: Artur Grottger and Juliusz Kossak, but the real explosion of this theme took place in the art of Young Poland at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. The classic here is Teodor Axentowicz, who portrayed himself in the costume of a Hutsul, and created at least ten versions of The Feast of Jordan. Three students of the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow did the most to popularise the Hutsuls – Kazimierz Sichulski, Władysław Jarocki and Fryderyk Pautsch, the son of a forester from Delatyn, who wandered together through the villages and high uplands. They jointly created an image of a people not spoiled by civilisation, living in harmony with nature and ancient customs.

The executioner dressed as a doctor

Paintings depicting pipe-smoking highlanders, highlander women worth sinning for, Hutsul weddings, parties, processions, and funerals sold like hotcakes. This was not just a local phenomenon, as the epidemic of ‘peasantomania’ spread across modernist Europe. Poles, sensitive to freedom slogans, coined the saying: ‘The falcon will not survive the cage, and the Hutsul captivity’. The symbol of highlanders’ expression became kołomyjka (from the town of Kolomyia) – a dance requiring above-average endurance and a sense of balance. The most impressive of the musical instruments was the three-metre trembita, formerly made from a hollowed-out spruce trunk, now made of brass.

In guidebooks, you could read that the Hutsul Region is ‘the most interesting historical monument of ethnography in Europe’. In the upper Prut River basin, villas and guesthouses sprang up like mushrooms. Members of the ruling Habsburg dynasty used to spend their summer and winter holidays here. After Poland regained its independence, this trend grew even stronger. The Chornohora and Gorgany Mountains attracted fans of wandering. It was here that Polish scouting was born, and the first tourist trail in the country marked out. Before 1939, the length of marked trails exceeded two thousand kilometres and, in the Gorgany alone, the Polish Tatra Society maintained twelve mountain shelters (there are none in this area today). The state supported tourism. Those going to the ‘Hutsul Feast’ could count on a 50 percent train ticket discount. There was a seasonal train from Warsaw and Lwów to Vorokhta, advertised with the slogan ‘Skiing, dancing, bridge’.

Successive towns and villages were turning into resorts. Dubbed ‘Hutsul Davos’, Kosiv was famous for its health resort run by Apolinary Tarnawski. This physician was a hydrotherapy fanatic, and applied drastic treatment methods: patients had to sleep with the windows open, exercise, do physical work, and walk barefoot in the morning dew. He forbade eating meat, smoking, and drinking alcohol. He condemned obesity and believed in the healing effects of fasting. The guests had swimming pools, sunbed terraces, and solariums at their disposal. At that time it was a modern facility, with a gate featuring the inscription ‘Own yourself’ leading to it. Surrounded by mountains, Kosiv became the second favourite place of rest, after Zakopane, for the Polish intellectual, artistic and political elite. Even those in perfect shape would visit.

The Hutsul myth grew stronger by the year. Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz who, accompanied by Vincenz, climbed the highest peak of the Chornohora range, Hoverla, described the experience in a style worthy of a literary aesthete: ‘Gentle mountains, blue gorges, seas of mountain ridges covered with meadows, flowers, flowers and flowers and, above all, a peculiar people, intelligent, interesting, picturesque, with unusual artistic sensitivity.’ Józef Wittlin saw Pokuttia in a completely different light. In his pacifist novel Salt of the Earth, immediately hailed a literary sensation and translated into many languages, he wrote: ‘the woman, vodka and religion: these are the three pleasures that protect the soul of the dark Hutsul from despair and hell on earth’.

The bear wanders west

The National School of the Ceramic Industry, which trained potters and tile makers, had already been operating in Kolomyia since 1876. Hutsul decorative motifs began to seep into industrial design. Traditional handicraft was still dominant in such villages as Żabie upon Cheremosh (now Verkhovyna). In this largest village in pre-war Poland, with a population of 10,000, there was a theatre where only amateurs performed. In turn, the pride of Vorokhta was a ski jump, older than the Wielka Krokiew in Zakopane. Nearby Yaremche boasted a waterfall on the Prut River, Dovbush’s Stone, and a railway bridge, a true masterpiece of engineering. The 65-metre stone span – the largest in Europe – found its way onto tourist postcards, becoming a model for Alpine transport route builders. The last Polish investment in the Eastern Carpathians was also impressive: a five-storey astronomical and meteorological observatory, dubbed the ‘white elephant’ by the locals, was built on Pip Ivan, the third highest peak in the Chornohora.

The final act of the September 1939 tragedy took place in Pokuttia: the Polish government, the high command of the army, and thousands of military and civilians fled to Romania via the border bridges over the Dniester and Cheremosh rivers. For them, this was often a definitive farewell to their homeland. For the local population, it heralded the end of the world as they knew it. The Soviet occupier closed the Art-Deco Hutsul Museum in Żabie. The exhibits were stolen, and the building torn right down to its foundations. The bridge in Yaremche was blown up by the Nazis. Abandoned by its staff, the ‘white elephant’ turned into a ruin. The murder of Jews, and the displacement of Poles, radically changed the cultural landscape of Pokuttia. During communist rule, the depopulated Bieszczady Mountains became a substitute for the Gorgany. This was also where the ‘king of the Carpathian wilderness’, the bear Turul from the popular novel for teens by Józef Bieniasz, went in its post-war editions. The Hutsul Region, like everything related to the Borderlands, became a taboo subject.

The largest collection of works by Aleksander Bachmiński can be found at the Historical Museum in Sanok. The collection of Hutsul folk art from Lwów was transferred to the Ethnographic Museum in Krakow. A cross and commemorative plaque in Ukrainian, Polish and Yiddish were erected on the slope of Kostrica, where Vincenz’s house stood. It bears the following inscription: ‘Estates, domains and houses crumble into dust, but what is human remains and holds the future in its embrace’.

Author: Wiesław Chełminiak

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki