When exactly 105 years ago, on 11 November 1918, the military operations ceased and the armistice ended the Great War the world was waiting for the accords of the peace conference which was to be held soon to determine the future of the world. A question remains: what did the main victorious powers offer Poland?

by Marek Kornat

Let us bear in mind that on 3 June 1918 the prime ministers of 3 allied powers (France, Great Britain, and Italy) made a political declaration that “independent and united Poland with free access to the sea is a necessary condition to lasting and just peace and rule of law in Europe.” Later Roman Dmowski deemed the Versailles declaration of the Entente prime ministers the greatest triumph of his diplomacy and a clear proof of a breakthrough in the struggle for joining the Polish cause with the Entente Powers’ policy. The Polish nation was given a right to independence, but the Polish borders were still a matter of controversy and struggle. Its territory could have been marked out in such a way that Poland would have been a small state with its western and eastern territory reduced and devoid of access to the sea except for unrestricted access to the port of Gdańsk.

It is my objective in this essay to focus on the comments and opinions uttered by western statesmen in the second half of 1918 and at the end of that year, that is, before the peace conference and after the Versailles Declaration of 3 June 1918. Of course, I am aware of how much has been written about this topic.

I.

Let us begin this overview with France, the power most favorable to Poland. After the fall of the Russian Empire and the Bolsheviks’ removal of Russia from the Entente camp there was a need for some other country in the east to turn against Germany on account of its objective interests (and not sentiments). That country could be reborn Poland. In line with the above assumptions, a memorandum regarding Poland drafted by the French ministry of foreign affairs in Quai d’Orsay on 20 December 1918 clearly states that “the safety of France requires a strong power on the eastern German border.”

The French government was guided by its homeland’s raison d’État, which consisted in striving for weakening Germany as much as possible. The objective was to prevent it from reclaiming its leading position in continental Europe and making it more difficult for Germany to consider seeking revenge for the fiasco of 1918. The only way that could be done was to give Poland back at least a substantial portion of its lands taken away by Prussia during the partitions along with Upper Silesia. Of course, such Poland would have to have its own coastline so as not to be at the mercy of Germany, which had Gdańsk. French minister of foreign affairs Stephen Pichon said in one of his memorandums that future Poland would have to be “very strong and very powerful” (“très grande et très forte”).

There was another factor acting to Poland’s benefit — the fact that it constituted a geopolitical buffer between Bolshevik Russia and the German Reich, which had to deal with armed communist revolts. A merger of those two revolutions posed a great danger to Europe. In the autumn of 1918 it was noticed in Paris that “Poland is now a barrier between Bolshevism and the German revolution.” The issue of reconstructing the “eastern barrier” (barrière de l’Est) was of a profound importance to the French along with the dictate to maintain “fundamental solidarity with England” as its main ally. With time, however, it was to occur that those two assumptions would be extremely difficult to reconcile with each other.

The French political discourse of 1918–1919 contained the conception of isolating ‘sick’ Russia with a ‘sanitary cordon’, and Poland was to be that cordon’s key element. Even though the objective to prevent the Bolshevik expansion played a significant role in the Paris government’s actions, one must admit that its most important objective was to erect the anti-German ‘eastern barrier’.

We know of no specific document drafted by the French diplomacy at the end of the Great War with regard to the future border between new Poland and Germany. However, it would not be a mistake to assume that the resolutions adopted by the Commission for Polish Affairs (led by former ambassador Jules Cambon) during the Paris Peace Conference in March 1919 more or less overlapped with the French wishes in that regard, which had been specified earlier. As we know, that commission postulated that Poland should incorporate entire Greater Poland with Poznań, Upper Silesia (without a referendum), and also Gdańsk Pomerania with Gdańsk without any reservations, while in Warmia and Mazury there was to be a referendum. That was definitely a lot. Back in 1917 no Polish statesman could dream of incorporation of such vast areas.

As far as the eastern border of the Polish state was concerned, the French were much more restrained. They looked to Russia, the non-communist one of course, hoping that the Soviet tyranny was temporary. Let us remember that on 10 January 1917, that is, just a few weeks before the outbreak of the February Revolution, prime minister Briand declared that the matter of Poland would be left for Russia to decide as its internal affair.

In the autumn of 1918 the French expectations regarding the future border between Poland and Russia could be summarized in 2 points. First of all, it was to be marked out in such a way so as not to hamper either a future French-Russian alliance or prevent a desired Polish-French treaty. Secondly, the French definitely wished to prevent the fall of the new Polish state under the blows dealt by the Soviets and for its survival as a component of the French ‘eastern barrier’ and the ‘sanitary cordon’. Poland was to fence off Europe from Bolshevik Russia and, more importantly, serve as an eastern substitute ally until Russia’s rebirth without Lenin in power. One thing remains certain: the collision between George Clemenceau’s postulate to rebuild ‘national Russia’ and Pichon’s conception of ‘strong Poland’ was obvious. But it was not disclosed by the French.

II.

The British imperial point of view opposed creation of small national states. Those were accepted unwillingly when they had already become an unavoidable reality. The basic objective of the British government, whose position on major international matters was very much subjected to prime minister Lloyd George’s personal opinions, was not so much to maintain the ‘equilibrium of forces’ in Europe as, first and foremost, to prevent excessive weakening of Germany so as not to make it a ‘degraded superpower’ as that was likely to contribute to a new war in Europe.

The idea was for Germany and future non-communist Russia not suffer too much for the benefit of the new Polish state. The authors of the British policy thought that the more the 2 states would suffer, the more likely a future Russian-German treaty would be. And such a treaty was expected to be tantamount to an unavoidable war on a large scale.

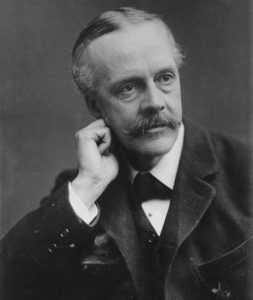

In the spring of 1917 it became obvious that it would be impossible to peacefully establish order in Europe without creating some Polish state. Freed from czarism, Russia agreed to Poland’s independence though on condition of its entering into a ‘free alliance’ with its eastern neighbor and marking its eastern border by the future Russian constituent assembly. Thus London’s opposition to the revival of Poland became a thing of the past. But let us bear in mind one more thing: as late as in the autumn of 1916 the British minister of foreign affairs Lord Balfour (Curzon’s predecessor) practically opposed Poland’s independence but spoke in favor of “some kind of home rule for Poland.” That was what he said in his memorandum to the government on 4 October 1916.

Lloyd George’s views led to a conception of creating a small Poland, closely confined within the ‘ethnographic’ borders, that is, devoid of the eastern provinces and without its territory expanded at Germany’s expense. First and foremost, such Poland was not to disturb the efforts to set the European distribution of forces in order. The British saw no need to degrade Germany by removing it from the group of superpowers as it did lose the war, its navy, and its colonies.

The British politicians saw the establishment of the Polish ‘corridor’ to the sea as particularly dangerous to peace in Europe. It seemed an anomaly without benefits. According to the London government, the only practical and feasible solution was to give Poland free access to the free port of Gdańsk. British statesmen also thought that Poland had no rights to Upper Silesia. One of the most industrialized regions in Europe, it was to remain a part of Germany, even if only to ensure that it had money to pay the war reparations.

One could say that if the British government had been solely responsible for drafting the peace accords, then Poland would have received only Greater Poland with Poznań. Luckily, that was not the case.

Of course, the British politicians and diplomats opposed giving new Poland any territories in the east. The doctrine in use was that of a small, ‘ethnographic’ Poland. There was also one more reason why shifting Polish borders further east was undesirable. According to the British plans for the world order, it was a bad idea to lessen Russia’s role in Europe. ‘Pushed out’ of Europe, it would turn to Central Asia, which was against the British strategic interests.

The last but not the least important reason why the British were reluctant to satisfy the Polish territorial aspirations was that they feared that the new Poland would become France’s ‘client’ state. When the cannons fell silent in Europe, the British began to increasingly fear the threat of French hegemony on the continent. That generation’s political imagination was affected by history — the memory of the actions of Louis XIV and emperors Napoleon I and III was still alive.

III.

Enslaved Poland undeniably enjoyed a great deal of support, though the Italian statesmen had an overall cautious attitude to the Polish cause. As far as the Polish borders were concerned, the Rome government’s stance was shaped in relation to the French and British policies. That had been true since the first days of the Great War, when Italy was still neutral. In many regards the stance of the government in Rome (prime minister Vittorio Orlando’s and minister for foreign affairs Sidney Sonnino’s) was closer to that of the British government than that of the French one.

But as a historian I must remark that after the 29 March 1917 manifesto of the Russian provisional government which recognized Poland’s right to independence the Italian government deemed that the reconstruction of Poland would be an “iron guarantee of lasting peace in restored Europe.” As soon as in June 1917 — superseding the French and the British — Sonnino declared his support for Polish independence at the Chamber of Deputies in Rome. He wished Poles “reconstruction of united and independent Poland.” That was the first such explicit declaration made by an Entente prime minister. Sonnino then repeated it publically in the speech he gave during the celebrations of the 100th anniversary of Kościuszko’s death on 25 October 1917.

Initially, Italians were enthusiastic supporters of the conception of nations’ self-rule as they expected that it would bring them benefits. In April 1918 Rome hosted the Congress of Oppressed Nationalities, attended by representatives of the nations in Austria-Hungary and delegates of the Polish National Committee. Then, however, the Italians noticed that the principle of nations’ self-rule hampered their plans to realize, at all cost, the accords of the Treaty of London of 26 April 1915. Consequently, they began to distance themselves from it. They planned for Italy to emerge from the war with territorial gains. Those, however, were not awarded to them. President Woodrow Wilson, the first advocate of Poland’s revival, voiced the fiercest criticism of Italy’s plans.

Since the Spring of Nations in the Italian political thought there had been the recurring idea to support conceptions of the restoration of Poland as a country belonging to the Latin civilization and turned against despotic Russia. The greatest Italian statesman of the 19th century, Camillo Cavour, publically supported Polish aspirations to independence. But in the situation at the end of World War I there was a growing conviction that future Poland would be France’s subordinate ally, while the Italian-French relations were markedly worsening.

Vittorio Orlando’s left-of-center successor Francesco Nitti proved a politician particularly unfavorable to Poland, but that occurred later, after the Peace Conference. Nitti replicated Lloyd George’s entire conception of ‘ethnographic Poland’ and in his book Peaceless Europe he criticized Poles’ aspirations to a large Polish state as severely as John Maynard Keynes did in his famous book The Economic Consequences of the Peace. But that happened later.

Italy was undoubtedly the weakest of the allied powers. Its voice could be decisive only in a situation when the more powerful states differed in their opinions with regard to the form of the Polish state. It could also prove valuable as a compromise offer if the powers could not reach an agreement. After the Peace Conference that proved to be the case with Upper Silesia’s territorial affiliation — a matter where Carlo Sforza played a significant role.

IV.

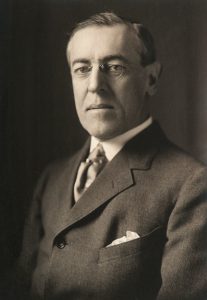

The first foreign statesman who publically recognized Poland’s right to independence was of course U.S. president Woodrow Wilson during his speech on 22 January 1917. Preparing his country to war on the Entente’s side (6 April 1917), Wilson eventually rejected the previous conception of ‘peace without annexation’, which would have been highly unfavorable to Poland as it would have prolonged our enslavement.

The famous speech Wilson gave before the Congress on 8 January 1918 included the Fourteen Points that specified the conditions of future peace. Point XIII called for the establishment of a sovereign Polish state covering the territories “inhabited by indisputably Polish populations” with “a free and secure access to the sea.” The existence of future Poland was to be guaranteed by a special international convention, probably one similar to the solution adopted by the 19th-century powers with regard to liberated Belgium. Consequently, the new Poland was to have a status of a neutral state, which would have prevented it from entering alliances.

Though extremely important, Wilson’s declaration made on 8 January 1918 specified neither the western nor the eastern borders of the new Poland. And neither did it determine the form in which it was to have access to the sea, that is, whether it would have its own coastline or the free port of Gdańsk. Most generally speaking, one could say that the American statesman was in favor of as ‘ethnographic’ as possible delimitation of the territory of the new Polish state. He demonstrated the same approach to the marking out of all other disputed borders on the European continent.

Not only a historian should know that even though the ‘ethnographic principle’ was beneficial to the Polish nation as far as the marking out of its border with Germany was concerned, that same principle threatened the Polish territorial aspirations in the east. Wilson’s idea of ‘nations’ self-rule’ was undoubtedly beneficial to the restoration of the Polish state, but it logically led to the adoption of the ‘ethnographic model’ — that is a small, weak Poland, one that even its inhabitants would regard as unable to exist. Thus the rule was self-contradictory. But a Poland other than the ethnographic one could not be substantiated on the basis of Wilson’s principles of healing the international relations.

The American statesman’s attitude to Poland’s territorial problems was to a large extent a function of his vision of the future of the post-war world. And here one should mention, first and foremost, his faith in the effectiveness of the League of Nations. Wilson truly believed that borders should not be a matter of priority. He thought that a new, powerful institution would give the world means to settle disputes and ensure protection of human and civil rights. Seen from such a perspective, national borders seemed less important than before. Today we know that those assumptions proved totally ungrounded.

Analyses of Wilson’s international conceptions tend to pay too little attention to his opinions regarding Russia. “As long as Russia is not a living part of Europe there shall be neither peace nor victory,” Colonel Edward House, the president’s closest co-worker, used to say. He also professed that if wronged, Russia would ally itself with Germany, and that would result in “all nations east off the Rhine turned against France, Great Britain, and the United States.” House’s American biographer G. Hogdson deemed those words a prediction of the Hitler-Stalin pact. These views sound very similar to the British ones summarized above.

In his note dated 10 September 1920 U.S. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby reminded just how much the American diplomacy was attached to the idea of indivisible Russia. In the autumn of 1918 the U.S. government was in favor of only three territorial concessions on the part of Russia: the Congress Kingdom for Poland (which was recognized by the provisional government of Russia in its declaration of 29 March 1917); Finland, which declared independence on 6 December 1917; and Armenia, whose nation was the victim of the first genocide in the 20th century. Russia was to become a confederation, which was postulated by Colby’s predecessor, Robert Lansing, in his 21 September 1918 memorandum for the president. Such an organism would give the nations of imperial Russia some kind of self-rule, but within the framework of indivisible Russia.

*

In the autumn of 1918 the western powers based their stance with regard to the Polish cause not on sentiments, but on their own interests. Such are the iron laws of international politics. The situation at the end of the Great War confirms that the western powers’ attitude to the Polish cause was basically a function of their attitude to Germany and Russia.

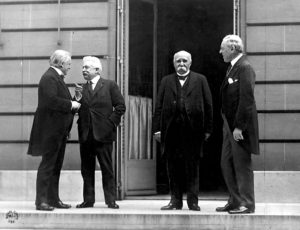

The French and British statesmen thought that Poland owed its independence exclusively to the Allied Powers’ victory. Widespread in the West, that conviction was aptly illustrated with the 24 June 1919 letter sent by Peace Conference President Clemenceau to Polish Prime Minister Ignacy Jan Paderewski. The former politician demanded that Poland sign the treaty on protection of ethnic minorities’ rights. “[…] I must remind you that it is thanks to the efforts of the countries on behalf of which I am honored to address you that the Polish nation is regaining its independence. […] Whether Poland can safely possess the territories [it regained — M. K.] depends on the support of the assets these countries shall bring into the League of Nations.” The conviction that “through the triumph of their armies the Allied and Associated Powers gave Poland back the independence it had been unjustly deprived of” was something like a cannon of thinking in Paris, London, and Washington after 1918.

But in fact the Polish state was revived not as a result of the victorious states’ mercy, but as a result of the Great War and the defeat of the three partitioners, which created a geopolitical vacuum on their ruins. The total upheaval that occurred had been unthinkable at the begining of the 20th century. Nevertheless, it did become reality.

The new geopolitical configuration in Central and Eastern Europe laid foundations for the system of national states. ‘New Poland’ was created in ‘new Europe’ even though it proved impossible to create a lasting equilibrium of forces. But “Poland was not a spectator of the birth of is independence,” as PM Maciej Rataj (later Speaker of the Sejm) rightly observed in the Polish parliament in July 1919.

In 1918 there was no country in Europe or elsewhere that wished for a strong and relatively large Poland, particularly one encompassing all of the major Polish centers. Nevertheless, the establishment of the state whose territory satisfied almost all territorial postulates of the Polish political elites proved possible. That did not happen only because Poles had put up both a diplomatic and a military fight for their country — the decisive factor was that Germany and Russia lost the war at the same time.

Of course, the Allied Powers’ policy would not have undergone such a profound transformation in Poland’s favor if it had not been for ‘diplomacy without letters of credence’, which was conducted so skillfully by Dmowski and Paderewski, though I shall not discuss it here as it is a topic for a separate essay. Besides, these issues have been relatively well-known for a long time.

Author: Professor Marek Kornat – Polish historian, sovietologist, sources editor, essayist, director of and professor at of the Section for the History of Diplomacy and Totalitarian Systems of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw, and professor at the Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw.