The development of a new political landscape in Central Europe after World War I was by no means something temporary. About probably the most difficult moments in the modern history of Poland and about the irrationality of a fragmented history we talk to Professor Andrzej Chwalba.

polishhistory: How did Poland in 1919 differ from other countries in Europe?

Andrzej Chwalba: Actually – in almost everything, especially if we compare Poland with the countries of Western Europe. The borders of the countries in the West and their political systems, had practically not changed. They could carry on with their pre-war politics. Sure, they had to nurse their own wounds and work to rebuild the losses from the war, but they didn’t have to form anything from scratch. They also didn’t have to convince anyone that they deserved a place on the map of Europe – whilst Poland did. Poland had to convince the Western elites that the new, post-war geopolitical landscape in the East, was not the result of mere chance, but that it signified a permanent order.

So the first comments from the West were unfavourable?

Scepticism was dominant in 1919. It was common to believe that the new shape of Europe was no more than the result of luck for the nations of Central Europe, and that there was no guarantee that it would be a permanent change. It was widely considered that although the Vienna system, on which the European order had been based, had definitively fallen, nonetheless certain of its ideas, remained permanent, forming the foundation of a new system: the Versailles system. This was supported by the fact that Europe was divided, albeit informally, according to spheres of influence, as well as that it was carried out by the victorious European superpowers and the United States, a new ‘Concert of Superpowers’. These states considered themselves authorized to decide about borders, indirectly about state political systems, also about how Russia would look and what her borders would be. That’s why from the perspective of Warsaw, Kaunas, Riga or Prague a great deal of work had to be carried out to convince the winning powers that the new states constituted the idea of a nation state and that they are not a freak historical event, that the nations which called them into being, had the right to a dignified existence and self-determination.

But cleaning up after the war was necessary in the whole of Europe.

Yes, but it had a very different profile in France or Belgium, and a different one in Poland, where it was necessary to form a new state. Perhaps it is a truism to say it, but I think we have to constantly remind people of this: Poles found themselves in a state comprised of three, even four different parts, since there existed strong differences in status and legal issues between the Kingdom of Poland and the so called ‘taken lands’ (Western Krai) located beyond the River Bug. For example, in the Kingdom of Poland, due to the fact that these lands, had been a part of the Duchy of Warsaw (1807-1815), mortgages existed on properties, which meant there was a solid ownership law. Meanwhile in the ‘taken lands’, this law was absent. This resulted in wide ranging consequences of a legal nature to do with the right to land and property. This thus had an enormous impact on legal practice in the interwar period.

History is vast, it is certainly not only made up of political history. However, is it not the case, that by putting the focus on social history, we risk losing the context of Poland’s right to self-determination and the shaping of its own politics?

Quite the opposite: the practice of factual, fragmented history, is irrational. Going too deeply into specialised areas of study, we overlook the context, which necessarily completes them. It is as if we were describing a character while looking only at their shoelaces and focusing on how they were made – meanwhile we don’t see the shoes, the clothes, we don’t see the person. On the other hand when we concentrate on social history, the person becomes incredibly clear, but the political background is lacking. Therefore limiting ourselves to both social history as well as factual history makes no sense. There is only one history, integral: economic, cultural, social and political. And this mix provides a challenge for specialists of global history, trying to put different perspectives together in one text.

The founding father of this school, Fernand Braudel, was able to write a global history, but is this something today’s researchers can afford to do? When we want to write about the 20th Century, it quickly becomes apparent that we have at our disposal, an enormous number of sources, first-hand accounts and historical facts and we face a Sisyphean task.

With regard to the 20th century, despite great difficulties, such global history works are appearing. However, my book, dedicated to the year 1919 in Poland, was not intended to be an example of a complete synthesis, but it also wasn’t meant to be description of one year, conducted in a chronological way from New Year’s Eve to New Year’s Eve. At the same time, a textbook format did not appeal to me, because, in order to achieve that, we have to have a specific period of history, such as, for example, the 19th century, First World War or the Interwar period. Only then is it possible to apply the ‘global history technique’. Let’s not forget though, that the subject of Braudel’s work were a few hundred years – he could allow himself to write a global history.

In contemporary debates, the theory that treats the First and Second World Wars as two sides of the same conflict, divided by a 20 year interlude, has become well established. At the same time, from the point of view of Polish history, political culture and widely understood traditions, the 20 year interwar period was significantly more than just an interlude, it was a period of fundamental significance.

Such an understanding of history, of the first half of the 20th century, takes away the right from a number of states, to their self-determination, and even existence in general. It is an acceptance of the idea that the development of a new political landscape in Central Europe after World War I was something temporary. In this way, it is unfairly implied, that the 1920s and 1930s were a series of tensions and armed conflicts. It is understandable that this is how it was seen by German and Russian politicians; however, it is curious that Western politicians such as de Gaulle and Churchill followed in their footsteps. Whereas European historians avoided forcing this view about the so called new 30 Years War: 1914-1945.

Do you want to suggest here, that the 20 year interwar period in Europe was a period of peace? That would surely be an overstatement.

Let’s look at the facts: the number of conflicts after 1921 is small. It was not until the Civil War in Spain (1936-1939) that it signalled something new, although of course the Anschluss in Austria by Germany as well as the breaking up of Czechoslovakia, which took place in 1938, were conducted in a peaceful way. It was a return to the old model: a change in borders in Europe took place only with the approval of the powers. The war only started on 1 September 1939. Until this time, conflicts were, on the whole, fought somewhere far away outside of Europe, in Asia and Africa.

Did feelings of pacifism after the First World War, play a role in this?

Yes, for sure. The Great War did indeed cause an explosion in pacifist feelings, and this greatly explained the lack of reaction from the Western Allies to the war in Spain and afterwards the outbreak of fighting in September 1939. In the West, the war formally began on the 3rd of September 1939, but there was no agreement for the active involvement of the Allies either from the side of the politicians and military, nor from wider society in Britain and France. Even in the autocratic states of Central Europe, pacifist feelings were dominant – completely the opposite to totalitarian states. In totalitarian states, society had become overpowered by the state, becoming the subject of the work of propaganda units, as in Germany, Italy or Soviet Russia.

The ideology of non-intervention practiced in France and Great Britain had strong roots in the trenches of the First World War. That is why, in the 1930s it was said: let’s do everything, to save peace – from this came the popularity of the slogan: ‘peace at all costs’. It was not the effect of mental aberration or cowardice on the part of French and British politicians, as they were later accused. It was, in effect, a realistic judgement of the situation. Neither the English, nor French or Belgians, were ready to go to war in 1939, either in a technical or a mental sense. At the same time, this goes against the theories of Western politicians and diplomats, that the First and Second World Wars were simply two sides of the same conflict.

Let’s turn again to the years 1918 and 1919. Jan-Werner Müller writes that Europe after the First World War was ‘the Molten Mass’, in this way showing how deeply the conflict had ploughed through and destroyed a world of ideas and values, and what goes with them, a social consciousness. Taking the term ‘the Molten Mass’ as a starting point – when did it definitively start to ‘cool down’ or cease?

I am not a fan of this term, although it is true that after 1918, there was a lot of chaos in Europe in the sphere of beliefs and ideas. It was in the first instance caused by the implosion of liberalism, as it was supposed to halt the war machine and it failed. Secondly the crisis of social democracy, as a result of the growing attraction of communist ideals. Thirdly the fall of authorities such as the German Kaiser, Austrian Emperor, Russian Tsar or Ottoman Sultan. They had been treated by society as institutions of trust. At the end of the war, these rulers were judged to be responsible for starting the war, as a result of which, they had to pay a high price. But stripping them of their positions, didn’t solve the problem for millions of people, who once again began to look for figures in whom they could place their trust.

The trend towards authoritarianism was a consequence of the hunger for authority?

Without a doubt. The fact is that, in the case of Germany, the substitute for the Kaiser turned out to be Adolf Hitler, and for the Sultan in Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Pasha (Atatürk). In Central Europe, the need to find an authority, who would provide support for people, led to the development of authoritarian systems, which we can hardly consider surprising. It was a trend seen across Europe, from Mannerheim’s Finland to Metaxas’s Greece. However, evidence of instability can be seen, not from the fact that we have to do with ‘the Molten Mass’: instability resulted from the loss of a political compass, which the strong authority of a ruler, had naturally embodied.

In that case, when can we speak of the stabilisation of the Polish state, when was its basic foundation laid?

It seems to me that there is no such caesura and it is not possible to find one. There is no exact moment from which we can trace that the fate of Poland’s statehood was sealed, it is, rather, a series of closely connected events. The most important question was the building up of an administration: a central and regional one. Optimists first thought that the merger and the rebuilding of a legal system could be completed in a few months. A Codification Commission was set up at lightning speed, but it quickly turned out, that it was not able to rise to the difficulty of the task. A few, or even a few dozen years of work were needed for a cohesive national law to be formed. Although there were no new legal codes, nonetheless in the autumn of 1919, Poland was sufficiently well organised to confront internal and external challenges. So, with a certain degree of simplification, we can treat the end of 1919 as a visible sign of stability.

But it was not just law that was the problem.

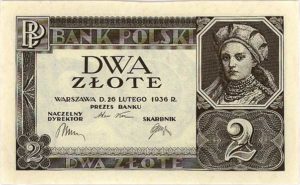

Of course, the next challenge was the lack of a national and widely recognised currency. Władysław Grabski, an otherwise excellent Minister of the Treasury, assumed in 1919, that it would be possible to adopt a new Polish currency within a few months, which would replace the Polish mark. Debates thus started regarding its name: złoty, lech, kościuszko. However it quickly became clear, that his optimism had been premature. The war with the Bolsheviks had decimated the budget: it was necessary to put aside 50-60 per cent of its total! Try to imagine a situation in contemporary Poland, in which half of the Polish budget goes to the military. All investments are frozen, pay is significantly lowered, welfare is decided by external donors and education is barely functioning. This was the basic problem, as all Poland’s great plans had hit a barrier – the war. All plans had to be ordered towards one end – not allowing what had happened in November 1918, the regaining of Polish independence, to be lost. Without a victory on the fronts, there would be no Polish state – all other problems had to wait. The huge needs of the army and the lack of a balanced budget led to rampaging inflation. Under such circumstances, it was difficult to carry out currency reform. This had to wait until 1924.

Under such conditions, there was not much left to a revolution.

Taking into account the low standard of living of millions of people and unfulfilled basic material needs it was possible to believe, that the situation would lead to a revolution. Lenin, when he was planning a Bolshevik offensive towards the West, was convinced, that such a high budget spending on the Polish army, in connection with epidemics, poverty, queues and criminality, would result in the disintegration of the Polish state and lead to a full blown revolution. He wanted to enter Poland, not because he felt the Red Army was stronger than the Polish Army, but because he was certain of an approaching revolution. Not only that, he also believed that some of the Polish soldiers would come over to the side of the Red Army and that, then, the red flag would fly above Warsaw from Sigismund’s Column.

Discussions about how Poles acted during the Polish-Bolshevik war have lasted for the best part of several decades, since the 20 year interwar period, and keep coming back. If, in the spring of 1920, in a region known for being particularly patriotic, 60 per cent of those eligible to serve registered to enlist in the Polish army, should we consider this result high or low?

This requires a consideration of the context. If we put it next to statistics of mobilisation carried out by the invading powers in August 1914, 60 per cent is a disaster. Whereas if we look from the perspective of Bolshevik Russia, Poland’s neighbour, it turns out that this 60 per cent is not such a bad result, because in some regions the lack of willingness to enlist, reached 80 per cent. In any case, it is worth taking into account, that in the young armies of neighbouring countries, problems were even greater. Lithuanians were escaping to Latvia, the Latvians to Lithuania, some to West Prussia or the Free City of Gdansk. We should add that in other regions of Poland, the percentage avoiding enlisting did not exceed 20 per cent.

Was it the peasants who did not want to fight for their ‘masters’?

Avoiding enlisting to the army was a problem for two societal groups in particular. On the one hand, it was indeed the Polish peasants, who didn’t fully understand the reasons why they were supposed to join the army since they had already fought for so many years. Moreover their national consciousness was often still immature. But enlisting in the army or the decision to absentee depended, significantly, on the approach of local leaders: where some encouraged men to march to the barracks, whereas others openly opposed this. From this came situations, where in one community almost everyone enlisted into the army, and in the neighbouring community – almost no one. Of course the influence of the communists was not without significance, especially in the East, where they called for a boycott of army recruitment.

The second social group unwilling to enlist was the Jewish population. A substantial proportion of Jews did not go to enlist because they believed that the Polish state was not their state. In 1919, the military looked on Jewish absenteeism with a pinch of salt, but only a year later, there appeared an urgent need to fill the personnel squadron of the army. Recourse was made to the fact that the Jews enjoyed the same rights as others in the state, therefore they should have the same obligations. Since they were citizens of the Polish Republic, they could not be freed from responsibility. The peasants even posed the question, why should they have to join the army, if the Polish authorities tolerated the absence of Jewish recruits. All of this resulted in substantial tension.

At the same time, it is worth mentioning that the level of desertion in the Polish army was comparatively low, nonetheless it did happen. It was caused by discontent with the harsh barrack life and the poor food. Soldiers complained about the American soya and sweetcorn and rebellions even broke out over herrings. The second reason for discontent was the low army allowance entitled to the soldiers, as the Polish army could not afford more. Germans joining the army in 1914, received significantly higher sums.

In this context, should we view 1919 as a deciding year for the rebirth of Poland?

It was indeed the founding year of the Polish state, although the 11th of November 1918 remains a symbolic date. When mentioning the founding year, what I have in mind is that, if we had not had many months of effort beforehand, the state would not have formed – its structures would not have been able to function. We could go on lengthy discussions about the functioning of the state and its institutions, but it could not have been different. There were very few educated people who possessed the right experience, especially outside of Galicia. In the Prussian partition, there were no Polish officials at all, there, even the janitors in the German courts, were solely German. The Polish state had to be created from almost nothing and encourage Generals to serve and organise the army, which was able to successfully defeat the Bolsheviks in 1920. Everything centred around these two things: the state and the army, the army and the state. That is what distinguished the year 1919. There would be no further years of the Polish Republic, if it were not for the determined effort of Polish society and its ruling elites in the year 1919. In this, lies its beauty and strength.

Interviewer: Michał Przeperski

Translation: Blanka Konopka