The June 1989 elections and the formation of the Solidarity government of Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki were earthshaking events in Poland’s recent history. Even though the communist authorities knew their power was slipping away, at the beginning of 1990 the secret police (Służba Bezpieczeństwa Security Service) was still firmly under their control. Up until the very end, Security Service officers waged a concerted campaign to cover their tracks. It wasn’t until 31 January 1990, that they finally received an official order to halt this criminal practice.

by Tomasz Kozłowski

From 1989 to 1990, revolution was spreading throughout Central and Eastern Europe. Things sped up when it became clear that Moscow was not going to defend its comrades in East Germany, Poland or Hungary. The secret police officers in these countries were well aware of that these communist regimes were falling apart. They were also convinced, that in the face of oncoming changes, they would be the first ones held to account. After all, for years they had functioned as the armed forces of the Communist Party – keeping people under constant surveillance, controlling and intimidating not only the political opposition, but the entire society. They had acted with impunity up till this moment but now they needed to begin covering up any and all traces of their activities.

The infamous East German Stasi was busy destroying damning documents – historians estimate that 10 to 40 percent of the giant archives were shredded (all the files, if laid side by side would stretch for 180 kilometers!). To this day, attempts are still being made in Germany to reconstruct some of the documents that were shredded – several million euros have been invested in the apparatus and program to help reassemble them. The destruction of these files by Security Service officers was one of the main reasons behind the assault by protesters on the Stasi headquarters in January 1990.

The Czechoslovak secret service was also very effective in destroying their documents – it is estimated that approximately half of all their operational files were shredded, including about 95 percent of documents related to the ‘enemies of the system’, i.e. democratic opposition activists. A similar situation took place in Hungary. As Polish intelligence reported: ‘files proving collaboration or documenting agents’ personal activities, as well as bookkeeping, were destroyed. Reports of damages are backdated and apply only to the most important documents. The administration of the ministry is considering the possibility of seizing the buildings of the Ministry of the Interior [as in East Germany] and is preparing to destroy all documentation.’

To this day, we do not know whether all these operations were carried out on the initiative of those in charge of the secret service, or under pressure from the KGB. Both options are quite possible. The KGB, depending on the circumstances, was active in ensuring the destruction or seizure of secret service documents from certain other members of the Soviet bloc. In January 1990, a group of Soviet experts came to Poland – it was suspected that they wanted to seize some of the documents related to Polish-Soviet cooperation. According to Polish intelligence, some files were even transferred to Moscow, as was the case with the Stasi: ‘Documents concerning cooperation were microfilmed and sent over to the Soviet service.’ In some cases these were considered ‘friendly favours’ – for example, the Security Service was informed by the Czechoslovak Secret Service that documents sent by Poles were successfully being destroyed, so there was need to fear them being uncovered.

Destroyed, burned, stolen

In Poland, the destruction of documents began shortly after the June 1989 elections. Although Solidarity managed to form a government with its own prime minister, the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of National Defense remained under communist control. General Czesław Kiszczak continued to serve as the head of this Ministry of the Interior, having held this position since 1981.

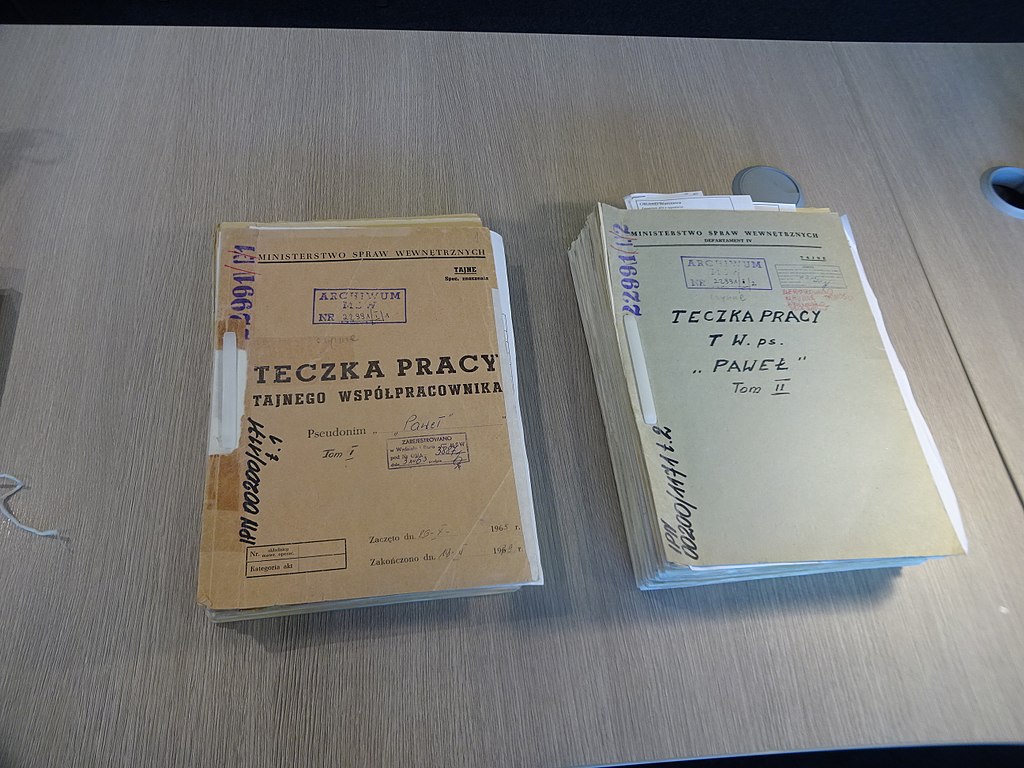

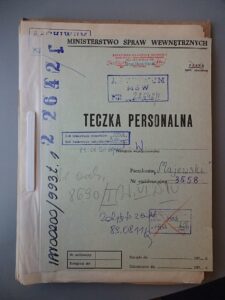

In July 1989, during a telephone conference, General Henryk Dankowski, then the head of the Security Service, recommended his subordinates start destroying ‘useless’ materials. Although euphemisms and jargon were used, it was clear to everyone that this was an order to destroy compromising documents. It was not the only institution that reacted in this way. At the same time, potentially damning documents ‘produced’ by those in charge of the Polish United Workers’ Party were destroyed. At the top of this list were the transcripts of Politburo meetings, which has the potential to reveal what lay behind some of the most important political decisions of the 1980s. The party leadership appointed a special commission consisting of archivists from the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party, the Ministry of the Interior and the Security Service to ensure that particularly sensitive documents were transferred to special services. At the same time, counterintelligence was systematically destroying its archives; some of these documents related to their activities against the democratic opposition in the 1980s. Even the Prison Service ‘cleaned’ its archives, destroying reports on the surveillance of political prisoners serving sentences during the regime’s existence. Within a few months, the Communist Party and the repressive state apparatus was able to put its entire past to the torch. Undoubtedly, however, the Security Service carried out the most thorough action because it had the most extensive and damaging documentation.

In the first place, its officers wanted to hide the truth about their activities, in particular illegal ones. Though a few documents have been preserved from the 1980s, these were obviously overlooked when the Security Service was busy deliberately violating the law.

The officers also tried to cover their tracks as secret collaborators and the authorities often protected them from being revealed, stigmatized or subject to revenge. At other times, however, they wanted to secure their interests. For that reason, not all documents were destroyed – some were ‘privatised’, i.e., stolen by security officers who wanted to obtain an insurance policy for the future. The most famous case of such theft is the appropriation of files proving Lech Walesa’s cooperation with the Security Service in the early 1970s by General Czesław Kiszczak. This cooperation took place before Walesa’s involvement in the activities of the democratic opposition, but [considering Walesa’s importance in the Solidarity movement] Kiszczak apparently hoped that it would serve as an effective tool for political blackmail. In the mid-1990s, Zbigniew Siemiątkowski, the minister responsible for special services, explained: ‘Twenty-some thousand former Security Service officers are currently retired or out of the service. It must be assumed that at least 1/3 of them have interesting information. Controlling them is a problem in and of itself […] With such blackmail, there is such an old rule saying that a threat is more dangerous than any actual action. I am aware that somewhere in the hands of the former officers of the Security Service and the Office for State Protection are documents that have the potential to harm someone.’

Documents were destroyed in several ways. The most effective way was to transfer them to paper mills, which were equipped with special devices for recycling and paper-making. Documents packed in bags were thrown onto a conveyor belt leading to a vat filled with paper pulp. On 30 October 1989, about 10 tonnes of documents were transported in trucks from Warsaw to the paper mill in Konstancin; these were mainly documents on the surveillance and persecution of Catholic clergy. If a specialized infrastructure for destruction was out of reach, simpler methods were used. The use of shredders was common – just as in the case of the Stasi archive. Some of the documentation, especially microfilms, could be burned in ovens within the headquarters. The stoker of the Security Service building in Siedlce claimed that he had burned so many documents in the winter between 1989 and 1990 that he did not use any fuel for central heating. In turn, officers from the Security Service in Poznań remembered how, in their headquarters on Kochanowski street, the boiler burst as a result of burning too many documents.

In the end, some documents were transported to secluded places and burned there. ‘We would purchase petrol with our own money and pack the documents and go outside the city. Within a few metres from the fire, we formed a circle, making sure that not even the smallest piece of paper could escape,’ an officer from Krakow recalled. The problem was that someone could notice the fire. For example, when officers from Starachowice took documents to the forest on 20 January 1990, they were seen by witnesses who alerted local Solidarity officials. It was also more and more difficult to rely on the officers themselves. In October 1989, the Security Service officers confiscated some of the documents to the Milicja (police) unit in Szczęśliwice and destroyed them there. Policemen present at the time revealed everything to Gazeta Wyborcza – the newspaper led by democratic opposition activists – which reported the story and informed the prosecutor.

To date it has not been determined to what extent the archives were damaged and it is difficult to estimate the fallout. The operation was carried out chaotically, and the success of each Security Service unit varied widely. The prosecutor investigating the case in the 1990s tried to estimate the extent of the damage: ‘In one of the commands I was told that three quarters of the documentation was destroyed, in another – over half. However, it is not known how much of the documentation was kept in each unit; and how much of it was destroyed in each particular case is not known either. So there is no reliable answer to this question.’ The greatest authority in this matter – Antoni Zieliński, head of the archives of the intelligence agency, which in the 1990s took over the Security Service documents, stated that 50-60 percent of files were destroyed, although not in all regions equally. For example, in Gdańsk, which was the cradle of Solidarity with a strong opposition milieu, nearly 95 percent of the documents were destroyed.

The fire needs to be put out

Weren’t Solidarity activists and members of the democratic opposition aware of what was happening? Why didn’t they react? The answers to these questions are not easy ones. First of all, the operation was hidden for a long time. When single facts came to light, hardly anyone was able to see the whole picture. For example, one of the Solidarity senators was reporting on some documents having been destroyed in his electoral district. However, he told this to the deputy of the Minister of the Interior, who was probably well aware of the situation. Meanwhile, the senator admonished him: ‘it gives the impression that you have no control over the service you command, sir […] This case with the destruction of documents is completely not conducive to defending the Security Service.’ He claimed that he himself was convinced that the action was not directed from the centre. However, the Ministry of the Interior and the Security Service remained entirely under the control of the communists and the old staff and Solidarity had almost no knowledge of what was going on inside these institutions.

One very significant contribution in putting the spotlight on individual cases was made by the Sejm Extraordinary Commission to Examine the Activities of the Ministry of the Interior. It was headed by an activist from the opposition organization Freedom and Peace and newly elected MP – Jan Rokita. The commission was set up in 1989 to investigate unexplained deaths in the 1980s as it was suspected that Security Service officers were behind many of these cases. The aforementioned General Dankowski, head of the Security Service, was so concerned about the work of the commission that he recommended his subordinates speed up the destruction operation: ‘the commission may be interested in what might be interpreted as a violation of law by officers during martial law and later. All materials (…) should be destroyed, liquidated.’ And indeed, members of the commission quickly understood that key documents were disappearing and some issues would remain unexplained forever.

One such case was the destruction of the archives documenting the persecution of the priest Adolf Chojnacki, who was involved with the opposition. One repentant officer of the Security Service had reported that there was a written document outlining plans for the killing of the priest. When members of the commission arrived at the Security Service unit and asked for these documents, they learned that this key evidence had been burned by the colonel in command. The longer the commission was operating, the more everyone learned about similar cases taking place all over the country. What’s more, officers who did not want to lose their jobs began informing Solidarity members about colleagues who were destroying documents. Employees of the Ministry of the Interior archives would come to Jan Rokita and point out the officers who were transferring documents to the paper mill.

Rokita, with this convincing evidence, called upon Prime Minister Mazowiecki to intervene. He had no success. Out of desperation, Rokita sent a letter to the prime minister and to Bronisław Geremek, chairman of the Citizens’ Parliamentary Club, consisting of MPs and senators of Solidarity. ‘I would not like to be mentioned in the future by historians as the one who was to be blamed for the destruction of these materials,’ he wrote. His letter began circulating among the Citizens’ Parliamentary Club’s MPs and senators. What’s more, the issue of document destruction was described in an article appearing in the national newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza. People in power began to pressure the prime minister to take decisive steps. Then something unique happened – the Citizens’ Parliamentary Club members issued a critical resolution regarding their own prime minister. Up till then Solidarity had attempted to maintain an unbroken facade of support for Mazowiecki, however, internal divisions were coming to light.

The club finally adopted a resolution: ‘Recognizing that the Security Service was one of the foundations of the Stalinist system and that its activities pose a threat to the socio-political stability of our state, we ask the government to immediately secure its operational and archival materials and to take action to resolve the Security Service. The establishment of an institution which would protect the state should be carried out boldly.’ The prime minister decided to increase pressure on the head of the Ministry of Interior Czesław Kiszczak. The latter recalled an exchange of views: ‘Prime Minister, we are following the rules and it would be better if we destroy some documents. They include things that compromise neither the ministry nor the Security Service, but the former opposition, and many of your colleagues. Mazowiecki replied that they would protect documents from unwanted people and it is better not to burn them at all. As you wish, sir, I replied and ordered that the burning of the documents stop.’

Indeed, on 31 January 1990, Kiszczak issued the order: ‘I prohibit – until further notice – the destruction of all working, operational and archival documents.’ At the beginning of February, the Security Service leadership was dismissed nationwide – the meeting was held under the ‘absolute compliance with the prohibition of the Interior Minister on the destruction of all documentation, even drafts and waste paper’. However, Kiszczak’s order did not end the procedure of removing documents. They were still being destroyed, though on a smaller scale.

The destruction or theft of documents made it difficult to ensure that victims received justice and the perpetrators were punished. It is symptomatic that both archivists and officers who were destroying the archives, as well as those who gave the order in the first place, were not punished. Their cases were usually closed. The destruction of the Security Service documents between 1989 and 1990 cast a shadow over the beginnings of the democratic Polish state and to this day casts a shadow over any assessment of Poland’s political transformation.

Author: Tomasz Kozłowski – PhD in political sciences, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin