Although representative assemblies are usually seen as a product of modern liberal democracy, their heritage was formed much earlier, as early as the 16th and 17th centuries. How did early modern parliamentary culture make its mark on culture and what can it tell us about contemporary representative institutions? These, among others, will be the subject of research and discussion at the conference Recovering Europe’s Parliamentary Culture, 1500–1700: Concepts, Methods, Approaches, to be held in Krakow in June 2022.

Natalia Pochroń: Planned to be held at the Jagiellonian University in June 2022, the conference Recovering Europe’s Parliamentary Culture, 1500–1700: Concepts, Methods, Approaches is devoted to early modern parliamentary culture. What can we understand by this notion?

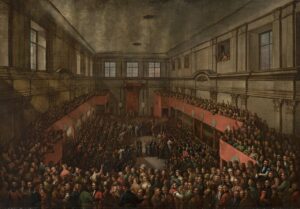

Dorota Pietrzyk-Reeves, Institute of Political Science and Interntional Relations, Jagiellonian University in Krakow: It is difficult to formulate a clear definition of ‘parliamentary culture.’ The term refers to representative institutions and a whole range of issues connected with them – the self-perception of these bodies, the functions they perform, the levels on which they function, such as political and legal culture, but also their participants and observers. This concept relates to the broader meaning of assemblies, seen not only as a place of law-making, but also as settings that generate ideas and influence formation of political culture. It is this cultural aspect that interests us in our international research project ‘Recovering Europe’s Parliamentary Culture, 1500-1700’ the most. For while the structure of representative institutions or the procedures of their operation have already been fairly well researched, their functioning in the cultural dimension – we are talking here about both abstract culture, the culture of ideas, and material culture – is still relatively unknown.

Why? No such research has been conducted before?

There has been relatively little research to date. Several factors come into play here. The main problem with comparative research on parliamentary cultures in early-modern Europe is that it has so far been conducted on a limited scale. While attempts have been made to compare the parliamentary institutions of Western and Southern Europe, Central Europe and often Northern Europe remains underrepresented in this research. I am talking not only about the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth – which is surprising given the fact that its parliamentary culture was one of the most vibrant in modern Europe – but also about the Kingdom of Hungary and even Russia. It also had assemblies, if only at the lowest, local level. The situation is similar in Northern Europe.

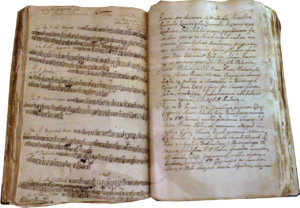

A certain challenge in this type of research may be the fact that to be reliable, it requires the involvement of specialists from many disciplines. It must involve an interdisciplinary, comparative and transnational approach bringing together researchers from different countries who have access to original sources often written in Latin or ‘old’ version of national languages and use various methods depending on their specific are of interest. These are also the challenges facing our project.

You already have such a research team. So what is the main goal of the conference?

It is true, there are many people who want to get involved in our research, but we still lack the methods and tools with which to conduct it. This is precisely one of the objectives behind organising the conference. We want it to become a forum for exchanging experience and ideas on how best to conduct this research. It is conceived as a kind of laboratory of ideas and methods, which, through the exchange of good research practices and the confrontation of various ideas and approaches should lead to the development of the best comparative methodologies for studying the parliamentary cultures of early modern Europe.

The name of the conference refers to a new approach to representative institutions. What is this approach?

Above all, it is about looking at their functioning in a cultural dimension, determining how representative institutions were inscribed in political, legal and material culture and influenced their development, but also how the evolution of culture, e.g. as regards religious tolerance, determined the way they functioned. We want to explore these relationships and look at them from a comparative perspective. The innovative approach is also expressed in the fact that we want to discover and show what is quite rarely highlighted, namely the similarities that exist between different parliamentary cultures, a certain common core of their functioning.

However, the representative assemblies in the various countries of late medieval Europe differed significantly – whether in terms of their organisation, their method of deliberation or their functions. Can we then speak of a common European parliamentary culture? Or would it be more reasonable to speak of a number of different, interconnected parliamentary cultures?

This is one of the questions we want to answer at the conference. The issue undoubtedly requires deeper research, but it seems to me that, despite appearances, there are quite a few similarities. Of course, there are also many differences – concerning procedures, ways of deliberation or the very deliberation culture. In this sense we can indeed speak of different parliamentary cultures. There is, however, a certain ideological core common to most of these assemblies, very strongly linked to the republican tradition and the principles of the mixed system, including the most important one – protection against arbitrary power. So I think we can speak of a common parliamentary culture in the sense of, for example, state-building. I hope that whether this is the correct approach will be verified during the conference.

The time frame of the conference is the years 1500–1700. Why this particular period?

Mostly because there is a very significant research potential here. Although it may seem a bit surprising, the Middle Ages have been very well researched in this respect, and there are many reliable studies and monographs. Later periods, that is the 16th and 17th centuries, remain relatively undiscovered in terms of parliamentary culture, and there is still much to be done. Besides, it is an extremely interesting period, connected with many events that significantly influenced the development of European political tradition and the formation of the modern state. On the one hand, there was the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation, which undoubtedly changed the political culture of many countries. On the other hand, these years saw the apogee of the development of parliamentary institutions, at least in some countries which shunned absolutism, and began to become the centre of political and life and political culture. So it is a very important period for the formation of representative institutions.

Does this period in any way influence the functioning of contemporary ones?

Definitely. It is a period in which the parliamentary legacy is being shaped, which would determine the development of representative institutions in the centuries to come. These early modern national assemblies were already built into the structure of a mixed government which later on becomes integrated into modern constitutionalism. They devlop deliberative and consensual practices as well as he whole idea of representation and political accountatiblity. They also contribute vastly to the development of the idea of freedom as the absence of arbitrary power, to use Skinner’s term. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are therefore crucial in many respects. It was during this period that certain values and principles emerged, including above all the principle of citizen participation in decision-making, which formed a bridge between the monarchical republic as a mixed system and representative democracy. Of course, this group of citizens was relatively narrowly defined – in Poland it included only the nobility, but elsewhere also the bourgeoisie, or as in England, all free people. However, what is at stake here are certain ideas that germinated at that time and, in a slightly modified form, have remained relevant to this day. So this legacy is very important and it is difficult to imagine the existence of later liberal democracies without it.

What other topics do you wish to address at the conference?

First of all, we will try to define what parliamentary culture is, because until now, it has not been defined in relation to this period. This will require in-depth, scholarly reflection. In addition, we will try to find similarities and differences in the way parliamentary practices were described in the 16th and 17th centuries, to examine how the representative bodies of the time were conceptualised and depicted in political texts and cultural products, including the visual ones. We will look at the subject of parliamentary debates and speeches in Europe at the time, which in many cases were considered a true masterpiece of rhetorical art. And, as I have already mentioned, we will try to find the best research methods for comparative studies of parliamentary culture in this period. These are the main issues we want to look at during the conference.

Why was Poland chosen as the venue?

Poland lies in the heart of Europe – this is undoubtedly one of the factors which played an important role here. But not the only one. The choice of Poland as the venue for this international conference was also influenced by the fact that in our project, at the first stage, we are primarily studying the three most developed parliamentary cultures of the period: Dutch, Polish-Lithuanian and English. For this reason, it made sense for the conference to take place in one of these countries. Everyone agreed that this country should be Poland, and Krakow to be precise. The event will take place at the Jagiellonian University, whose development coincided with the development of parliamentary cultures – in this we can also look to Krakow for certain models or inspirations.

How can you apply for participation in the conference?

Dorota Pietrzyk-Reeves: By replying to our invitation and sending in a short abstract of a proposed paper, which should be to the research focus of the conference. It needs to fall within the scope of such topics as attempts at defining parliamentary culture, the rhetoric of debates, the place of early modern representative assemblies in culture, and the way in which contemporary parliaments make use of this legacy. Our invitation is extended to both early-stage and experienced researchers from various disciplines such as history, political philosophy, law, literature, art and material culture. We wish to create as broad research forum as possible, allowing the study of diverse aspects and discourses.

Why is it worth taking part in the conference? What new contributions can it make to the existing research on parliamentarism?

First of all, we will search for a new perspective in research a new on parliamentary culture. Certain aspects have already been well examined at the level of national assemblies. What we are proposing is to go beyond the national contexts and look at this issue on a broader, transnational level. We want to broaden the research perspective, which so far has been limited mainly to the political and institutional-legal sphere and show how representative institutions have become part of the culture of societies and how they influence it even today. During the conference, we will try to refer, for example, to a new way of researching and comparing sources in a way which, I hope, will make it possible to see the broader context of the functioning of representative assemblies and their influence on the production of ideas and cultural patterns.

Such fresh insights may be of interest to researchers and help them approach their own research in a slightly different way. And it will allow us all to see how strongly the parliamentary culture of early modern Europe influences contemporary representative assemblies, and thus perhaps also to better understand the nature of their functioning and the challenges they face.

Interviewer: Natalia Pochroń

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin