The Constitution was the dawn of a better future. After 3 May 1791, there was time for supplementary laws to be passed, institutions to get to work, and for a new kind of politics to bed down during the last year of the Great Sejm. On the whole, the indications are very promising. On the one hand, the extraordinary optimism about the future was naïve, given the realities of international relations, but this aura of success – after so many decades of humiliation – did help to convince many doubters to support or at least accept the Constitution. The Commonwealth was thus able to demonstrate its enormous potential – says Professor Richard Butterwick-Pawlikowski.

Michał Przeperski: The Constitution of 3 May 1791 is said to be the first in the continental Europe and second modern constitution in the world right after the one adopted in the United States in 1787. Is it a legitimate thing to say so?

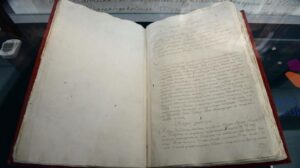

Richard Butterwick-Pawlikowski: I take a constitution to be a solemn legal framework which outlines, underpins and establishes the form of government, together with the relationship of citizens to their government, the whole being derived from the shared values of the community of citizens. The Law on Government (Ustawa Rządowa) or Constitution of 3 May 1791 is certainly such a constitution, although it was also a constitution in the older sense of the word – a law passed by the sejm (Polish-Lithuanian parliament or diet). Clearly the American constitution also meets these criteria. There are three alternative candidates for the world’s first modern constitution: Pylyp Orlyk’s Pacta et Constitutiones Legum Libertatumque Exercitus Zaporoviensis of 1710; the Swedish Regeringsform of 1719 (amended in 1720, 1772 and 1789), and Paolo Pasquale’s Custituzione di a Corsica of 1755. These are all extraordinary constitutional documents which deserve more fame than they usually receive. However, the first of these never came into force at all – it was the manifesto of an exiled Cossack hetman. The Swedish document of 1719 was only part of a wider constitutional settlement; it could be compared to the English Bill of Rights of 1689. The Corsican constitution lasted fourteen years before France crushed the Corsican uprising against Genoa and annexed the island. Of the early contenders, this one has the strongest claims, with some serious democratic tendencies, but it remained less comprehensive in scope than either the American or Polish constitutions. The Custituzione was at least as concerned with dealing with problems of the moment as with establishing the form of government for the future.

A characteristic of all these documents is their refreshing brevity, compared to later constitutions. The Constitution of 3 May 1791 left much detail unresolved, and its own exalted status was conferred on laws passed a little earlier (for the royal towns) and later (regarding the Union between the Polish Crown and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania). And yet it also explicitly provided a fundamental framework for the structure of society and the form of government, derived from the “will of the nation” (referred to in both the preamble and the fifth article). The much longer and more detailed French Constitution of 1791 was only adopted on 13 September 1791. Polish writers at the time recognized the (unwritten) English, American, Polish and French constitutions, and they assumed that each in turn was influenced by its predecessors. So to sum up, the Constitution of 3 May has a very strong claim to be considered the first modern constitution in Europe, but, really, eighteenth-century constitutionalism is too interesting a subject to be reduced to a contest for national bragging rights.

Which elements of the Constitution seemed to be crucial at the time of its adoption, and which are perceived as fundamental today, from the researcher’s point of view?

These days, in the context of joint Polish-Lithuanian celebrations of the anniversary, it seems as though the key element of the Constitution was the Mutual Assurance of the Two Nations passed on 20 October 1791. This resolved the studied ambiguity of the text of the Law on Government by reiterating the 1569 Lublin union between the ‘Two Nations’ of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. It safeguarded parity or alternations for Lithuania in shared government commissions and in the sejm itself. This solemn law’s reversion to more traditional terms, including the Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita), contrasted with the repeated emphasis in the Constitution passed on 3 May 1791 on ‘the nation’ (in the singular), ‘Poland’, ‘the Fatherland’ and ‘the country’. On the other hand, the Mutual Assurance also referred to ‘the Polish Commonwealth’ – evidently the names overlapped harmoniously. At the time, Stanisław August regarded the Mutual Assurance as a unanimous further legitimization of the Constitution. It must have contributed to the exceptionally high level of support for the Constitution expressed by Lithuanian sejmiks in February 1792. But the nagging question remains – why were levels of enthusiasm apparently lower at some sejmiks in the Polish Crown?

For contemporaries at home and abroad, the most controversial element of the Constitution of 3 May was the abolition of the fully elective monarchy, and the introduction of hereditary succession to the throne. The euphemism of “elective by families” fooled nobody, not least because the text of the Law on Government explained the disastrous consequences of interregna and the advantages of hereditary succession. However, the actual arrangements for the succession of the Elector of Saxony, followed by his daughter, envisaged a kind of election for her husband, who would then found a new dynasty of Polish kings. Catherine II of Russia was also alarmed by the provision in the fourth article of the Constitution (on peasants) that all those who immigrated to the Commonwealth would be personally free, able to choose to settle in a town and take up a trade, or else to enter into a contract with a landowner to farm land. She feared a mass exodus of serfs from the Russian Empire. This provision. under-appreciated in most later arguments among historians and polemicists, could well have led to the end of serfdom in Poland-Lithuania within a generation. The tsaritsa’s anxieties were shared in Berlin and Vienna, too, but those two courts were especially concerned by the civil and civic rights guaranteed to burghers in the “Free Royal Towns of the Commonwealth”. Would overtaxed burghers be content stay in the overregulated towns of the Prussian and Austrian monarchies, when exciting opportunities for liberty and prosperity awaited them in the Commonwealth?

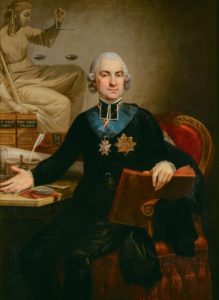

Much heat was also generated, both within the Commonwealth and outside it, over whether the Constitution had transformed a republican form of government into a monarchy. Catherine II hyperbolically complained that “arbitrary power” had been conferred on Stanisław August, and the counter-revolutionary confederates of Targowica and Wilno (for the Grand Duchy of Lithuania) made this charge their chief refrains. It’s certainly a vital question for researchers these days. How far did the Commonwealth’s form of government shift towards the limited, parliamentary monarchy which the king so admired in Great Britain, away from the uncompromising noble republican axioms of the past? This is a question about laws, institutions, practice, ideas, and above all – political culture.

The eighteenth century saw a long shift over many decades away from the assumption of an Aristotelian forma mixta, with aristocratic senators holding the balance between monarchical “majesty” and democratic “liberty”, towards a decisively republican form of government, which allowed for the growing emergence of the idea of a sovereign nation (leaving aside the question of its composition for the moment). During the second half of the Four Years’ Sejm, in 1790-92, I identify a shift towards the idea of partnership and trust between a stronger executive led by the monarch, and an effective legislature, voting by majority when necessary, comprising representatives of the sovereign nation unbound by sejmik instructions. That is to say, the principle of representation overcame that of delegation. Together with prompt and impartial justice dispensed by elected judges, this partnership was the basis for the king’s vision, partly derived from Charles de Montesquieu, the author of L’Esprit des Loix (1748). The “orderly freedom” assured to all in such a constitutional framework was contrasted by enlightened royalists and republicans alike with the “aristocratic anarchy” of old. However, traditional republican suspicions of central government remained strong, and this was reflected in the laws that filled out the Constitution of 3 May passed in the year that followed. Nevertheless, when war with Russia came in the spring of 1792, powers and responsibilities were heaped on Stanisław August.

This year we are celebrating the 230th anniversary of the adoption of this Constitution. In your book you present a wider background and the paths leading to its adoption. One question which seems to come back again and again is: wasn’t the adoption of this fundamental law a belated effort?

The solutions adopted in the Constitution of 3 May 1791, not to mention the persuasive strategies embedded in the text, were so strongly marked by the ideas and values of the late Enlightenment that it is impossible to transfer them imaginatively to the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, when the Commonwealth’s factual independence and sovereignty hung in the balance. That said, the impressive resilience with which the Commonwealth soaked up invasions and coped with profound political and economic crises from 1648 onwards had run out by the end of the Great Northern War (1700-21). The failure of the political community – during the reigns of John Casimir, Michael Wiśniowiecki, John Sobieski and Augustus the Strong – to adopt fundamental constitutional reforms which would have prevented foreign powers from exploiting interregna and the liberum veto to keep Poland-Lithuania weak, fiscally and militarily, was decisive.

After the consolidation of Russian hegemony around 1720, all efforts to repair the Commonwealth would face obstruction and sabotage. Moreover, from 1763 onwards, Catherine II tightened the screws, compared to the looser Russian “sphere of influence” which characterized the reign of Augustus III (after Russian troops had won him the Polish-Lithuanian throne). Fundamental reform could only be undertaken during the Four Years’ Sejm, because the Russian Empire was then preoccupied with wars against the Ottoman Empire and Sweden, and was also threatened by Prussia and Great Britain. The sejm was therefore able to cast off the Russian “guarantee” of the Commonwealth’s form of government, without facing Russian revenge for three and a half years – a window of opportunity.

Looking from the point of view of European Enlightenment, and from the perspective of long-lasting legal tradition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth how should we treat the Constitution of 3 May? Was it rather an element of change or continuity?

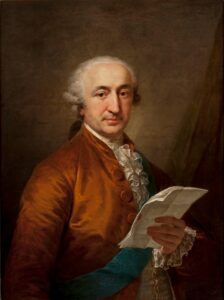

The Constitution of 3 May was strongly rooted in the traditions of the Commonwealth: ‘’liberty” was one of its key motifs, many precautions were included against the abuse of executive power, and the privileged szlachta (nobility) was placed first in the social structure outlined by articles II to IV. At the same time, the old republican idea of liberty – a legal framework, involving nobles’ political participation in the shared Commonwealth, which prevented a ruler from depriving citizens of their particular liberties and rights) – was enriched. The Constitution placed a relatively new emphasis, apparent in some Polish legal and constitutional treatises written in the 1770s and 1780s, influenced by strands of the Enlightenment, on universal, natural rights – freedom was the natural human condition; hence the direction of travel indicated in the Constitution: from a Commonwealth of privileged noblemen to a nation of all inhabitants of the shared Fatherland, enjoying some degree of individual liberty and property, secured by law and government. Hugo Kołłątaj pressed hardest in this enlightened direction, which complemented the king’s vision.

The other aspect of change that should be underlined is that “the will of the nation” was now active – expanding freedom and promoting prosperity – rather than passive – defending freedom from the monarch. A essentially familiar assumption was reinvigorated by the eloquent language of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. By the same token, unfettered national sovereignty was vital for the exercise of the national will, and so the idea and slogan of independence regained its centrality in Polish-Lithuanian political culture. That too is reflected in the text of the Constitution.

In the end, the Constitution of 3 May was overthrown by the Russian invasion in 1792. Alternative history is certainly not a matter of scientific consideration, but this question is coming back in a popular discourse: was there any chance to defend Poland and thereby save the new government established by the Constitution?

I have no objection to alternative or virtual histories, as long as they are plausible in the context of the time (and especially if they are based on actual discussions of the likely consequences of choices). It is nevertheless hard to construct optimistic scenarios in this case. The best one I can manage is that the angel of death came not for Emperor Leopold II or King Gustav III in the spring of 1792, but instead slew Catherine II. We would then have to assume that her eccentric son Paul I would have acted differently from his unloving and unloved mother.

The serious discussion among historians has generally focused on the chances of negotiating a compromise solution with Russia, either in the aftermath of 3 May 1791, or by prolonging the undeclared war which began with the Russian invasion of the Commonwealth on 18 May 1792. Yes, negotiations, involving the succession for Catherine’s grandson Grand Duke Constantine, should have been undertaken straight away. Assuming they failed, should the Polish-Lithuanian leadership have continued military operations in the summer of 1792, trying to defeat two Russian armies in battles before Warsaw, in the hope of forcing the Empress to negotiate directly, rather than adhering to the Confederacy of Targowica and sending the army to peacetime quarters – in effect, capitulating? That was the position taken on 23 July 1792, during the famous ministerial council, by Marshal Stanisław Małachowski. It was a high-risk strategy, which could have led to disastrous and bloody defeat. There was the danger, raised by the king, of a Prussian invasion in the west (the reverse scenario, we could add, to 1939). But it seems that at least some of the Russian soldiers and politicians, including Catherine’s young favourite, Platon Zubov, were indeed expecting prolonged resistance and direct negotiations at some point. The campaigns in the Crown and Lithuanian had not been the triumphant marches they had anticipated. What is clear is that capitulation on the empress’s terms meant the abandonment of the remaining cards – soldiers who had grown in confidence and overwhelming public support. Instead of being able to capture the counter-revolutionary confederacies from within, Stanisław August was forced into one humiliation after another, for himself and for the Commonwealth. With the benefit of hindsight, at least, it proved a grave error of judgement. Catherine II soon found it suited her interests to carve up most of the Commonwealth’s remaining territory again, this time with Prussia alone, as Austria was conveniently preoccupied by France.

Your book do not concentrate solely on the events of 18th century, but also pays attention to the criticism the Constitution was treated with in 19th and 20th century. Why was it a topic of such fierce discussions?

The American constitution, albeit amended, has shown extraordinary longevity. Could the Polish Constitution have done likewise? Well, it did contain a clause for its own amendment every quarter-century, which would have given it great flexibility. But of course it was only in force for less than fifteen months, and so the text became fossilized. Nevertheless, as we all know, in the summer of 1792 it was overthrown by the Russian army, who installed an oppressive and incompetent counter-revolutionary regime. By the time of the Insurrection of 1794, Kościuszko and the more radical insurgents already regarded the contents of the Law on Government as insufficiently republican and democratic. In turn the experience of the constitutions of the Duchy of Warsaw and the Congress Kingdom of Poland brought a more monarchical and ministerial approach to government than envisaged even by Stanisław August.

After 1830, the idea of simply restoring the 1791 Constitution became ever more marginal to émigrés and insurgents. The Constitution was firmly established as a symbol of the sovereign Polish national will symbol, whereas its contents were subsumed into polemics about the Commonwealth as a whole. Roman Dmowski, for example, bitterly criticized the Commonwealth of nobles while praising the Constitution as a corrective to its worst fault – indiscipline. The most common criticism has been that it failed to abolish serfdom, while modern Lithuanians have assumed – until the recent emphasis on the Mutual Guarantee – that the Constitution of 3 May abolished the separate status of the Grand Duchy and therefore was yet another Polish offence against Lithuania. Scholars and opinion-formers who first and foremost celebrate diversity have suspected the Constitution of being a step towards the homogeneous ethnic and Catholic Polish nation-state which they dislike. At the other end of the spectrum, the Constitution is denounced as a cosmopolitan masonic plot against the home-grown republican values of Catholic Poland. Either way, the revival of republican ideas and values has made the move towards limited parliamentary monarchy and the separation of powers suspect. And there has never been a shortage of commentators who have pronounced the breach with Russia provocative and suicidal. I take a different, far more positive view of the Constitution of 3 May.

Finally, from the point of view of today’s professional historian, what was unique in the experience of Constitution, which is still worth celebrating after 230 years?

The Constitution was the dawn of a better future. After 3 May 1791, there was time for supplementary laws to be passed, institutions to get to work, and for a new kind of politics to bed down during the last year of the Great Sejm. On the whole, the indications are very promising. On the one hand, the extraordinary optimism about the future was naïve, given the realities of international relations, but this aura of success – after so many decades of humiliation – did help to convince many doubters to support or at least accept the Constitution. The Commonwealth was thus able to demonstrate its enormous potential. The reforms of which the Law on Government was the keystone prepared Poland-Lithuania for the nineteenth century – a much better nineteenth century than the one actually experienced by the inhabitants of the region. The Constitution of 3 May shows us beyond doubt that the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was not a failed state, put out of its anarchic misery by better governed neighbours. That, of course, was the narrative they promoted, but it has since been shared by many Poles. On the contrary, the Commonwealth was a vital community of citizens, which was rapidly recovering its strength after a long crisis. “Orderly liberty”, much more than Jacobin radicalism, was infectious. And that was why the threatened absolute monarchies of Russia, Prussia and Austria dismembered the Commonwealth.

Interviewer: Michał Przeperski

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki