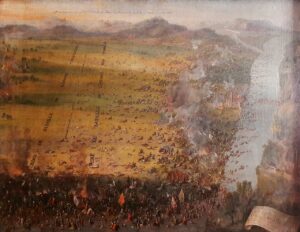

The victory achieved by John III Sobieski on 12 September in Vienna marked the defeat of the Ottoman army. It was one of the greatest battles of the 17th century, one of the greatest triumphs of Polish arms and, at the same time, the most painful defeat of the Turks. However, it did not mark the end of the campaign. Less than a month later, two more battles took place, which not only could have turned the tide, but almost ended in the death of the Polish king.

by Cezary Wołodkowicz

The position and plans of both sides

On 12 September 1683, the Turkish army suffered a painful defeat. The wagon forts and cannons were lost and Vienna was unblocked. However, the Turks were not completely shattered. The losses of the Ottoman army barely made up 15 per cent of its total. The Ottoman army could have resisted had it been able to catch its breath and restore discipline. The Turks retreated via the only possible route – east along the Danube – towards the great fortress of Győr. Already on 14 September, the Grand Vizier himself arrived onsite. There were many refugees under the fortress, as well as some of Murad Giray’s Tatars. However, the morale of these troops was dire. On 15 September, someone spread a rumour that the Giaours were approaching and panic broke out. Those who could, began to flee. The Vizier, however, took steps to save himself. Without waiting for news from Istanbul, he ordered the execution of those he considered cowards and traitors. He was also quick to name the culprit of the disaster. This was Ibrahim Pasha, the beylerbey of Buda, who was strangled to death following the Ottoman custom. To his post, he appointed Kara Mehmed Pasha, who was to play a substantial role in both battles of Párkány (now Štúrovo).

On 16 September, the vizier ordered a further retreat to Buda. There, the situation of the army worsened as dysentery began to rage among the poorly equipped army. However, news arrived from Istanbul: the Sultan had forgiven Kara Mustafa his defeat. After all, even Suleiman the Magnificent himself had failed to take Vienna. The Grand Vizier then set about rebuilding the discipline and morale of the army. He carried out a further purge among the command staff and also replaced Murad Giray with Haci Giray. Kara Mustafa recognised that the allied Poles and Austrians would target fortresses and castles in the Ottomans’ hands. Key were fortresses such as Esztergom and Nové Zámky, where he quickly sent reinforcements. On 5 October, when he learned of the allied march on the first of the fortresses, he ordered Kara Mehmed to come to its aid. He placed the majority of suitable troops, mostly cavalry, under his orders. All that was left at Buda was a demoralised force of common troops and the remnants of the vizier’s side troops. The Turkish allies, who could no longer be relied upon, were sent home.

Meanwhile, the allies were unable to agree on a joint plan of action. After the Battle of Vienna, they lacked the energy and initiative to capitalise on the victory. Disagreements quickly arose. The Elector of Saxony, John George III of the House of Wettin, refused to participate further in the campaign and began preparations to return. Count George Frederick von Waldeck did the same. It was difficult to persuade the Elector of Bavaria, Maximilian II Emanuel Wittelsbach, to continue the war effort. The biggest problem was selecting the target for the successive operation. Sobieski rightly opted for marching on Buda and forcing the battle and smashing the Turkish forces. He also wanted to win the support of his son, Jakub, as King of Hungary. The Austrian commanders, on the other hand, wished to move into northern Hungary, towards Nové Zámky, in order to quell the uprising there and restore imperial authority over the region. A compromise solution was chosen. The allied troops were to move east along the left bank of the Danube. The main idea was to cut off the Turkish troops in northern Hungary and Emre Thokoli’s kurutz insurgents supporting them from the main forces at Buda. As early as 19 September, on the insistence of John III Sobieski, the allied troops moved towards Bratislava. The Polish king wanted to finalise the campaign before the arrival of the autumn rains.

Towards Párkány

The allied march was slow. The army was weakened by the hardships of the campaign. Moreover, heat prevailed and fresh water was in short supply. Many Ottoman corpses flowed along the Danube, and those of local villagers slaughtered by the Tatars lay in the fields. In such conditions, diseases began to spread among the soldiers. Horses died en masse. According to research, some Polish troops were decimated by more than half. The majority of Polish soldiers also began to spend more time in the wagon forts, counting their booty and falling ill. Some left the ranks and returned to the country. The situation was similarly poor in the imperial troops.

There was a week’s standstill in Bratislava, with a lack of river-crossing facilities. The allies used this time to improve the situation of their troops. Hospitals were organised in the city. Efforts were made to replenish supplies.

On 2 October, the allied troops reached Komárno. The Polish army was then reduced to ca. 15,000 men. The same number of troops served under Prince Charles of Lorraine. It then became clear to all that the plan to besiege and capture Nové Zámky was unrealistic. The allied command accepted Sobieski’s plans – to mount an attack on Budapest and smash the Turkish forces there. The difficulty was in capturing the Danube crossing. The nearest one was between the small fortress town of Párkány and the heavily fortified fortress of Esztergom, located on the right bank of the river.

On 6 October, the crown army arrived a dozen or so kilometres away from Párkány. The approaches brought a couple of ‘talkers’ who, under torture, testified that there were several hundred Janissaries in Párkány and that, apart from the Esztergom garrison, there were no major Turkish forces in the vicinity. In view of this, the Polish king decided to strike at Párkány the very next day and seize the crossing by surprise. There he intended to wait for the remainder of his forces.

It had escaped the scouts that the Grand Vizier had sent the strong detachment of the aforementioned Mehmed Pasha to this area, numbering some 20,000 fine cavalry – Sipahis and Akinjis from Rumelia, Buda, Karaman and Sivash. This force was to receive support from the Tatars and Thököly’s army. Mehmed Pasha achieved quite a feat, crossing on the night of 6/7 October and taking up a position near the Párkány unnoticed. The Turkish commander accurately read the intentions of the allies and intended to fight them in a battle.

Párkány, 7 October 1683: a day of defeat

The Poles set off at dawn of 7 October. The crown army stretched out in the march in a long, slowly advancing column. Stefan Bidziński, the crown guard, walked in the advance guard. He led the light cavalry and two regiments of dragoons. At some distance behind him, groups of cavalry were advancing. The first under the command of Stanisław Jabłonowski, the Great Hetman of the Crown, the second under the direct command of the Polish monarch. They were followed slowly by the infantry and artillery under the command of Marcin Kątski, as well as two retreating Polish cavalry regiments. The imperial troops marched next. The march was closed by the allied trains.

Bidziński abandoned all precautions. He failed to carry out any reconnaissance, and some of his dragoons marched without lit fuses at their muskets. The crown guard was given a clear royal order – not to take any independent offensive action. He was to reach Párkány and await the rest of the army. He was only to strike if he saw the fleeing fortress crew heading for Esztergom and attempting to set fire to the bridge. In any case, he was not to press on randomly encountered Turkish troops, but to send a messenger to the rest of the army.

It was early in the morning. Bidziński’s guard entered the area between the hills near Párkány. From there it spotted a small Turkish detachment (according to sources, approx. 500 men). The Polish commander, thinking little of it, ordered a charge. The Turks failed to hold the field and quickly began to retreat. The Poles rushed in their pursuit. However, to their dismay, the main Turkish force – some 10,000–15,000 men – was in the nearest valley. The Polish troops came under fire from Párkány, while Mehmed Pasha’s troops charged from the front. The crown guard gave the order to retreat, yet it was too late. The Polish cavalrymen had to break through their own hurried dragoons, who failed even to fire a salute. The Polish troops became completely confused and began a panicky retreat.

On hearing the sounds of battle, Hetman Jabłonowski rushed towards Párkány. However, the Polish advance guard and the Turks on their backs fell into his ranks. Jabłonowski gave the order to form a battle line and also ordered the dragoons to rush forward to repel the enemy’s charge with fire.

A salvo by Polish dragoons halted the Turks only for a moment. Seizing the opportunity, the hetman threw his cavalry troops into a counterattack. The Poles pushed back their opponents. However, the Turkish commander himself drew reinforcements and engaged them in the battle. The Polish troops succumbed to the advantage and launched a disorderly retreat. Left to their own devices, the dragoons were surrounded and cut down.

Not much time had passed when the troops of John III Sobieski’s group emerged from behind the hills. The king immediately understood the gravity of the situation. He quickly sent messengers asking Kątski and the Prince of Lorraine, who were following him, for help. He himself decided to stop the enemy by forming the following battle line, leaving the right wing for the retreating Jabłonowski, placing Szczęsny Potocki on the left, and Marcin Zamoyski, Voivode of Lublin, at the centre. Barely had the Poles managed to get into formation when the Turkish cavalrymen rushed in on them. Kara Mehmed already knew that he was dealing exclusively with Polish troops. He therefore decided to make the most of the favourable conditions (the element of surprise and a larger army) and smash the Poles before the imperial troops arrived.

The Polish insurgents repulsed the enemy attack. However, confusion reigned. Orders overlapped, and the dragoons refused to dismount their horses. The Turks moved to retreat. Sobieski forbade a counterattack, fearing a ruse. However, the escape of the Turks prompted Jabłonowski’s troops to give chase. Thus, the formation was broken.

This was precisely what the Turkish commander had been waiting for. The Turks turned around and struck at Jabłonowski’s outstretched wing. Some of them broke into the gap and hit the remaining Polish troops from behind. Although John III Sobieski gathered a few troops and attempted to counter the new threat, the remainder of the Polish forces took this as a sign of retreat and began to flee.

The Polish formation broke in an instant. The troops mingled with one another. The slaughter began. Sobieski had barely managed to send his beloved son, Jakub, to the rear, when he suddenly found himself in the middle of a crowd overwhelmed by terror. Barely seven companions remained by the king’s side, including an unnamed Reiter, who shielded the king at the cost of his own life. He killed two Turks advancing on the monarch, shooting one with a pistol and stabbing the other with a rapier. However, he ended up being sliced up by others.

The Turkish pursuit continued for several kilometres. It was only stopped by the sight of advancing Austrian troops. Kara Mehmed ordered a retreat in the direction of Párkány.

Panic broke out among the allies. Rumours spread that the king had been killed. However, a short while later, John III Sobieski himself appeared, battered but healthy. The monarch did not lose his spirit; furious and eager for revenge, he even offered the imperial commander to resume battle. The latter, however, sensibly declined. Polish losses were considerable, and could have reached up to 1,000 men. Also important was the damage to the morale of the Polish troops and the royal prestige. During the meeting after the battle, the king’s opponents spoke out. There were voices demanding the retreat of the allies. The king objected, with the support of Charles of Lorraine, who pointed out that a retreat could risk even more than undertaking another battle.

While the Polish camp was in low spirits, the Turkish camp was euphoric. The Ottoman commander had succeeded not only in stopping but also in beating the ‘Lion of Lechia’. As a sign of victory, his sub-commanders decapitated the defeated and stuck them on the battlements of Párkány. It seemed even to the Turks that the Polish king had fallen for they found the body of his lookalike, the Pomeranian voivode Władysław Denhoff. Kara Mehmed ordered the head to be sent to the Grand Vizier. He received reinforcements in return.

Párkány, 9 October: a day of victory

During the day of 8 October, both sides rested and prepared for yet another clash. The Turks, having received reinforcements, had a force of 20,000 men. This army, however, consisted only of cavalry and had no infantry or artillery, apart from those positioned at Párkány and Esztergom. Kara Mehmed positioned his troops on the hills, parallel to the river Hron (at the rear of the Turkish army). The front of the Turkish troops was slightly oblique to the road from Komárno to Párkány. The right wing was stronger and closer to the allied troops. It was not difficult to guess that the Turkish commander’s intention was to smash the enemy’s left wing and push the rest of his forces towards the Danube.

John III Sobieski set about restoring discipline among his troops. Many of the soldiers who had been in the wagon forts were incorporated into troops and regiments. The Polish army numbered 14,000–15,000 men (6,000 infantrymen, 2,000 dragoons and 7,000–8,000 cavalry soldiers). The imperial army was similarly numerous (6,000 infantrymen and 9,000 cavalry soldiers and dragoons). The allies, however, had 56 cannons.

Sobieski clearly saw that the Turks’ position had significant disadvantages. In the event of defeat, Kara Mehmed had almost no way of retreat. The only safe crossing of the Danube was within reach of the allies. On the other hand, the hills and the deep and steep valley of the River Hron behind prevented an organised retreat northwards. The Polish monarch therefore decided to base his left wing on the hills, set up mainly infantry in the centre, and receive the main enemy attack there. The right wing was to act offensively. Its aim was to cut off the Turks from the bridge crossing to Esztergom and break up the crowd on the Hron River.

The allied troops began forming on 9 October at dawn. On the left wing stood the Polish cavalry and infantry in three lines, under the command of Hetman Jabłonowski. The first included hussar troops mixed with infantry regiments, the second with armoured cavalry and dragoons, and the third with weak dragoon regiments. At the extreme end of this wing stood ten light cavalry regiments. In the rear and in the gaps between the formations stood Kątski’s artillery forces. The imperial infantry formed in two lines under Starhemberg’s command stood at the centre, with field guns positioned in front. The dragoons were in the third line. The imperial cavalry lined either side of the infantry. Command of the centre fell to the Prince of Lorraine. The right wing under the command of Hieronim Lubomirski consisted of hussars in the first line, armoured cavalry in the second, and the remaining infantry and dragoon regiments in the third.

At approx. 9 a.m., on the signal of three cannon shots, the allied forces set off on a precise march towards Párkány. The progression of the allied troops was extremely slow. The commanders had to make sure that no gaps were created. It was not until three hours later that the Polish-Austrian forces approached Párkány. Their formation was oblique to the Turkish grouping. The left wing approached the enemy faster.

The Turks deployed their forces as predicted by the Polish monarch. He positioned almost half of his forces in the first line and the rest behind the centre in the form of three powerful retreats. According to his plan, Kara Mehmed began the battle by throwing 10,000 cavalrymen at the centre and left wing of the enemy. The Polish and Austrian infantry greeted the charging Turks with fire. Shortly after the salvo, the Polish hussars moved into the charge and drove the enemy back. At the centre, the Turkish attack was stopped by chevaux de frise and musket and cannon fire. Kara Mehmed reacted to the situation by reforming the formation and directing another attack only at the allied left wing. The Turkish engagement on the allied left wing was exploited by the Prince of Lorraine, who struck the Turkish wing with his own cavalry. Attacked simultaneously from the wing and the front, the Ottoman right wing was in disarray.

Meanwhile, Sobieski ordered the right wing to march slowly forward. The hussars proceeded with their lances folded so as not to attract the enemy’s attention. Unable to resist, the Turkish left wing launched its retreat. Kara Mehmed supposedly saw the danger and ordered the retreating troops to halt the manoeuvre, but to no avail. The left wing, fleeing in panic, mixed with reinforcements. Lubomirski’s troops fell into the disorganised enemy, and the slaughter began.

At this sight, the remaining allied formations joined the attack. Kara Mehmed was about to lose his head and was the first to flee. Some Turks managed to reach the life-saving bridge, but it was quickly shelled and destroyed by allied artillery. Only Kara Mehmed and 800 soldiers managed to make it to the right bank of the Danube. Some Turks attempted to swim across the river, but perished in its currents. Those crowded on the riverbank were fired upon mercilessly by allied infantry and artillery. A similar fate awaited the Turks fleeing north, who were stopped by the steep banks of the Hron River.

Polish dragoons and infantry immediately rushed towards Párkány. The fury of the attackers was heightened by the sight of the severed heads of their comrades, killed barely two days earlier. The Poles quickly broke into the ramparts. A fierce and merciless battle ensued inside the fortress, whose defenders were given no mercy. The fighting and melee with the Turks continued until late evening.

The battle ended in full victory for the allies. The Turkish army was completely crushed. A total of 10,000 dead Turks were counted on the field. The allies were to lose between 400 and 1,000 people. A small number of prisoners were taken, approx. 1,500, including Mustafa Pasha and Khalil Pasha, the beylerbeys of Silistra and Sivas, respectively. The victory restored the dominance of the allies and the prestige of John III Sobieski, who once again confirmed his skill and talent for commanding.

The Polish king did not make the mistake of 7 October, when he underestimated his opponent. Sobieski made excellent use of his superiority in artillery and infantry, forcing his opponent to fight on his terms. Kara Mehmed was let down by his allies, who failed to show up on the battlefield. The Turkish commander can be accused of overly weakening the left wing. An attack on the right wing would have caused considerable difficulties for the allies. However, by the same token, it would have facilitated an attack by the allied left wing. Although, on the other hand, there would have been a chance to evacuate more troops across the Danube. It seems, however, that the Turks had no hope of victory.

After Párkány

On 12 October, the allies began building a crossing to the other bank of the Danube. Reinforcements arrived for them in the form of troops from the Elector of Prussia and Bavarian forces, a total of approx. 6,000 men. The principal objective became the capture of Esztergom. On 20–21 October, imperial, Bavarian and Prussian forces crossed to the right bank. The day after, the first siege work began, building artillery positions and digging mine tunnels. The garrison defended itself quite bravely. However, on 27 October, after the first artillery shelling, the fortress commander capitulated, under pressure from the population. Four days later, the Polish king set off with his troops for a winter break; he insisted that they should spend the winter in Empire-controlled countries.

The defeat at Párkány and, above all, the fall of Esztergom, sealed the fate of the Grand Vizier. Kara Mustafa went to Belgrade, from where Mehmed IV had left earlier. On 25 December, he was visited by two Sultan’s envoys, who took the prophet’s seal and banner from his hands, after which they gave him a silk cord and, according to custom, strangled him to death.

Author: Cezary Wolodkowicz

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki