Becoming a national hero because one decided to obey the rules of parliamentary procedure? Being shown on innumerable stamps and posters, and what is more – becoming a part of a proverb? (“Kłaść się Rejtanem” means literally “to lie down like Rejtan”, but metaphorically – “to oppose something strongly”). Indeed this is what happened to Tadeusz Rejtan, who is well known for this one gesture. However, in order to understand how this 31-year-old became an undisputed hero in April 1773, it is first necessary for us to recall past circumstances and rules.

by Wojciech Stanisławski

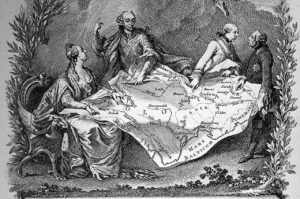

Times were tragic. The Republic of Poland weakened by wars, lack of internal order and pressure from external states was confronted with the necessity of accepting the partition, i.e. appropriation of part of its lands by Prussia, Austria and Russia. Notions of taking over some of the border territories to defuse the growing tension between European powers were discussed in St. Petersburg, Vienna, Berlin and Paris at least from the end of the 1860s. The very concept of partition, that is, the division of the lands of an existing and recognized state, was even older. Already in the 17th century, there were similar speculations in the Ottoman lands. In the case of the Commonwealth, the treaty of Radnot, signed in December 1656 between Sweden and Transylvania, assumed the same solution but fortunately remained only on paper.

In 1770, the situation was different. Prussia and Austria were keenly interested in the appropriation of the borderlands of the Commonwealth; Russia hesitated for a long time: its ideal was the Polish lands as a protectorate controlled entirely by St. Petersburg. However, in the face of pressure from Vienna and Berlin, French arbitration, and the progressive destabilization of the Republic of Poland, Russia finally agreed to the partition. An additional argument was the appropriation by Prussia and Austria of border counties under the pretext of “expanding the sanitary cordon”.

The nobility opposed St. Petersburg’s domination in Polish politics which was the immediate pretext for concluding the partition agreements. The radical wing decided to kidnap King Stanisław II August Poniatowski. The ill-considered and unnecessary action was abandoned after a few hours, and the king was freed, but the three neighbouring countries used the pretext of the lack of self-government and sovereignty of the Republic of Poland. In February 1772, the first Russo-Prussian treaty defining the course of the new borders was signed; in the autumn, Russia, Austria and Prussia gave an official announcement about the new political reality of the Republic of Poland.

War at that moment was out of the question the Commonwealth troops, with their low wages, were many times weaker than the troops of the partitioning powers who had been for a long time able to enter Polish lands without resistance, and later began to guard the “new” borders. The diplomatic resistance limited itself to a few notes addressed to European countries. The decorum which was valid in the 18th century, however, required that the decision about the partition be passed by the Sejm, i.e. the parliament of the victimized country. It can also be considered an element of perversity: the diplomats of the partitioning powers (the Russian envoy and minister plenipotentiary Otto Magnus von Stackelberg, the Prussian MP Gédéon Benoît and the Austrian Karl Reviczky) simply wished that the partition of the Republic be approved by the Sejm, which was convened on 19 April 1773.

So much for the circumstances. However, there was still an issue concerning parliamentary regulations. Under the “liberum veto” operating from the 16th century, the Sejm of the Republic of Poland could be dismissed (and its resolutions annulled) at the request of only one deputy. This principle, which was supposed to serve the unanimity of the deputies and enable them to slowly reach a compromise, became nearly pathological over the centuries. However, for the sake of the principles of the political system (as well as due to serious conflicts that could arise), it was still valid. One way to circumvent it was to recognize the Sejm as “confederate”, that is, making decisions (like the vast majority of representative bodies) by a majority of votes.

The aim of the political game was precisely such: the partitioning powers and the “realists” were convinced that even among the resigned or bribed deputies there could be one righteous man who would utter the “veto” formula, thus preventing the legalization of the partition of the country. To prevent this from happening, it was necessary to form a confederation. Adam Poniński, a chairman of the Sejm sessions, made such a proposal; he was completely devoted to Russia.

And this is where Tadeusz Rejtan, an envoy of the Nowogródek region, the son of a wealthy landowner Dominik Reytan, chamberlain of Nowogródek, enters the scene. A debutant in the parliamentary profession, he was, however, perfectly familiar with the regulations, and he saw the only chance to prevent the legalization of partitions in preventing the formation of a confederation. He “transferred” the formula of “civil objection” to a different level, objecting to the establishment of a confederation.

He raised this issue already at the first session of the Sejm, on 19 April, stressing that the Sejm was convened as “free”, not confederated. During the following dramatic 36 hours, he tried to prevent the formation of a confederation, using a kind of however anachronistic the phrase may sound in relation to the 18th century “sit-down strike”, sitting in the conference room and not leaving it even for a moment. And when, after the dissolution of another session of the Sejm, preceding the establishment of the confederation, the bribed deputies began to leave the room he threw himself at their feet, forcing them to trample him.

There were those who did it (according to testimonies, Jacek Jezierski, an envoy from the land of Nur, was the first). After 36 hours, Tadeusz Rejtan, exhausted and badly beaten, left the royal castle where the Sejm gathered, never to return to it.

What followed was just a sophisticated window dressing by the partitioning powers, the Polish deputies and politicians collaborating with them. The latter, outraged by Rejtan’s “diversion”, which had a wide impact throughout the country, were ready to confiscate the envoy’s property and threatened him with a physical trial. Representatives of the partitioning powers publicly expressed their appreciation for Rejtan’s courage, and the general of the Prussian army, Lentulus, even offered him military assistance for his safety. This allowed him to sign a few more “protests”. This was in vain, however, as on 18 September, a delegation of 99 deputies, fully controlled and paid for by the invaders, signed division treaties with representatives of the great powers.

Rejtan returned to his family estate in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Most likely, he permanently lost his mental balance, family legend says that he died as a result of a suicide attempt 240 years ago on 8 August 1780. Depicted in one of the country’s most famous paintings, and quoted in poems and adages, Rejtan remains one of the Polish “voices of objection”.

Author: Wojciech Stanisławski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin