In the spring of 1871, when Adolphe Thiers’ government fled to Versailles and the capital was engulfed in the flames of revolution, between four and six hundred Polish émigrés volunteered to fight under the red banner. Most of them had already experienced the smell of gunpowder, so they became the elite of the communard army suffering from a lack of experienced fighters. Going against a stronger and better-armed enemy was not new to them.

by Wiesław Chełminiak

Why did the Poles join the rebellion? Disillusioned with the attitude of Europe’s political elites, they saw their chance of victory in an alliance of peoples, in a popular revolution. ‘In every dispute between the satisfied and the discontented, a Pole must take the side of the latter,’ explained Roman Czarnomski, a veteran of the November Uprising, the Spring of Nations in Greater Poland and Baden, the Crimean War, the January Uprising and the Franco-Prussian War.

Since 1789, all the Paris revolutions had been successful. They toppled governments and were like earthquakes that triggered secondary political upheavals across the continent. The impoverished Polish émigrés had little to lose, and everything to gain. Accustomed to fighting ‘for our freedom and yours’, they dreamt of returning to their homeland with weapons in hand. They were buoyed up by the success of the Italian irredentist movement which, after many defeats, had achieved its goal, creating a united state.

Unlike the French communards, they were opposed to killing prisoners of war and taking hostages. Nor did they harbour any hatred for priests or monarchical monuments.

History remembers two of them best. They were both 34 years old, but apart from that they differed a lot. Jarosław Dąbrowski was a blond man with slick-backed hair and boyish features, whose short stature and leadership skills earned him the nickname Łokietek (Short/Elbow-high), referring to the warlike King Władysław I (1260– 1333). In émigré circles, he had more enemies than friends, unlike Walery Wróblewski, a man with impossibly tousled dark-brown hair, who was liked by everybody. Friendly, honest and always cheerful, even though he lived on the verge of poverty. In Paris, he was a printer and street lamp keeper. In Nice, he worked as a blacksmith’s assistant, which did not stop him from playing roulette.

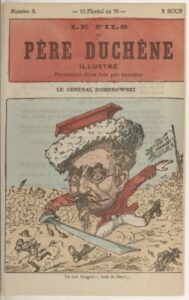

The Commune promoted Dąbrowski and Wróblewski to the rank of generals. They were both in favour of offensive action, but the poorly disciplined Parisian National Guard, composed of volunteers, was unsuited to such actions. They had to start by taming the anarchy in their own ranks. Thanks to the energy and courage of the Poles, it took the government army as long as two months to crush the revolution.

Leaflets for illiterate readers

They were born at the end of 1836. Walery on 27 December in Zheludok upon Neman and Jarosław on 13 November in Żytomierz (now Zhytomyr) in Volhynia. These lands were not seized by the Russians until the third partition of the Polish-Lithuanian state, but they immediately instituted a blunt police-military regime. Opponents of the new order ended up on the gallows or in exile. The repression intensified under Nicholas I, a primitive sadist called Palkin by his subjects. On one occasion, the Tsar visited a cadet corps school in Brest Litovsk. A nine-year-old cherub caught his eye, standing in a row with older boys. He took him in his arms, asked his name and origin. ‘Dąbrowski, a Pole,’ Jarosław replied. The monarch must have expected a different answer, because he furiously threw the child on the ground so that he lost consciousness.

His intuition was right, the cherub did not allow himself to be Russified, and when he grew up, he became a nuisance to the Russian empire. Having completed an artillery school, he was sent to the Caucasus, where he took part in the conquest of the territories inhabited by the Circassians. Distinguished with the Order of Saint Stanislaus, Dąbrowski entered the elite General Staff Academy in Saint Petersburg. His career was about to start. Many liberals studied there, disillusioned with the procrastination of the new Tsar Alexander II in introducing reforms. Influenced by forbidden books and his friendship with Zygmunt Sierakowski, the lieutenant decided that instead of complaining one should act, and became a pillar of the illegal officers’ organisation. He also made contact with his compatriots living in the imperial capital. Perhaps also with Wróblewski, who was studying at the Saint Petersburg Institute of Forestry.

Brought up in a patriotic home, Walery probably conspired already in a Vilnius middle school. However, the conspiracy formed by his older classmates, planning to overthrow Russian rule in Lithuania, was exposed, and the leaders were sentenced to several hundred hits with a stick and forced labour in Siberia. Wróblewski survived, and after completing his education was awarded the rank of second lieutenant. In early 1862, he was sent to the forest school in Sokółka, where he became an inspector. Meanwhile, Mr Short, or Dąbrowski, had applied for a posting on the staff of the Warsaw garrison. They were both preparing an uprising. Walery’s agitation also reached out to Orthodox peasants, whom he convinced that Poland’s independence would mean equality before the law, the abolition of serfdom and land ownership. He printed leaflets in Belarusian, but most of the villagers could not read or write.

Revolution for a hundred roubles

Dąbrowski found Warsaw gripped by political fever. The local underground, crippled by arrests and escapes of its leaders, welcomed him with open arms. By the spring of 1862, he was already the informal leader of the ‘reds’, as the patriots who apart from independence also sought social upheaval were called. About four thousand conspirators were under his command. On the captain’s initiative, the National Central Committee was established, the prototype of the government of the underground Polish state. ‘He had a volcano in his head and heart that was always erupting,’ was how one of his opponents of the time assessed Dąbrowski.

Referring to the recent example of Giuseppe Garibaldi, who with a thousand volunteers attacked and overthrew the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Dąbrowski claimed that ‘the most important thing in a revolution is boldness and speed of action, as a result of which forces that are small at the beginning grow like an avalanche’. The key to success was to capture Warsaw. He calculated that seven thousand well-commanded insurgents would suffice. The main target of the attack was to be the Governor’s seat, i.e. the former Royal Castle, and the Citadel, which contained the most valuable treasure for the conspirators: 30,000 rifles.

The plan envisaged street fighting and the building of barricades, but in fact its success depended on the attitude of the Russians. Dąbrowski was convinced that his friends in uniform would manage to take control of the Warsaw garrison. He himself intended to mount an attack on Modlin at night with two thousand insurgents armed with revolvers and daggers. The poorly guarded fortress was were weapons and other military equipment were stored. The captain expected that soldiers supporting the insurgents would arrest officers loyal to the tsar and open the gate. After the victory at the Vistula, the banner of the revolution would be carried deep into the empire.

Dąbrowski dreamt of repeating the November Rising. A determined handful of conspirators were to draw a multitude of those undecided behind them. ‘Those who are good Poles will go to the camp, and the others will be taken by force,’ predicted the leader of the ‘reds’. The patriots of 1830 were soldiers and had weapons at their disposal. Now they had to capture them from the enemy, bring them from abroad or manufacture them clandestinely in trusted forges and metal works. And the Committee’s coffers held just one hundred roubles. The ‘white’ rivals did have money but did not want to hear about a revolution.

World from behind bars

The ‘reds’ accepted the captain’s plan. In fact, its author threatened that, in case of refusal, he would implement it with the forces of the municipal organisation loyal to him. The uprising was to begin on the anniversary of the capture of the Bastille by the French, that is on 14 July. Given the state of preparations, that propaganda-carrying date was unrealistic. So it came to 20 August after all. The conspirators were in a hurry. They were afraid that the ‘whites’ would make a deal with the tsar and, after granting autonomy to the western governorates, the Poles would not want to fight for a higher stake. In addition, the authorities found some traces of a conspiracy in the army. Three officers were sentenced to death whose agitation activity (reading forbidden literature to their colleagues) the investigators managed to prove.

On the eve of the execution, Second Lieutenant Andriy Potiebnia, Dabrowski’s friend, shot the Tsar-appointed governor in the neck in Saski Park. The wound was not fatal, but it ended the dignitary’s career. The assassin took refuge in the flat of Dąbrowski’s life companion Pelagia Zgliczyńska. The Russians responded by dislocating their troops. Units in which many Catholics served were withdrawn deep into the empire and replaced with guard regiments, considered to be the mainstay of Russian sovereignty. A propaganda campaign against the Poles was also launched. Rebellious subjects of the tsar were called ‘traitors to the Slavs’.

Attempts to assassinate the new governor and leader of the moderates, Count Aleksander Wielopolski, failed. His grouping took power in the Committee and zealous Dąbrowski could do nothing about it, imprisoned since 14 August. Investigators suspected that the revolver used by one of the assassins belonged to him. Without the captain and his Russian friends, the insurrectionist plan was falling through. Meanwhile, Wielopolski – in the illusory belief that he had become master of the situation – was going out of his way to provoke the reds into action. In January 1863, he finally succeeded.

Locked up in the Warsaw Citadel, Dąbrowski was heartbroken when he learnt of the outbreak of the uprising. Given the situation at the time, he considered it ‘disastrous, a misfortune for the country’. He quickly pulled himself together, however, and planned a prisoner revolt and escape. Pelagia gave him a truncheon and a revolver during one of her visits. Unfortunately, the inmates of the Citadel considered Dąbrowski’s idea suicidal and refused to participate.

Disguised as a female servant

Wróblewski joined the fight in the spring of 1863. He commanded the insurgents in the Grodno area. His men were poorly armed, only a lucky few were able to boast of having a hunting rifle. There were not even enough scythes for everyone. In a clash with a regular army, the chance of victory was minimal. A forester from Sokółka, however, turned out to be a born partisan, he would fight the Russians, retreat into the forest, which he knew like the back of his hand, and would not allow himself to be broken. The uprising’s dictator, Romuald Traugutt, promoted him to lieutenant-colonel and ordered him to move with his unit to Podlasie and the Lublin region. The aim was to prolong the fighting in order to provoke foreign intervention, which had been promised to the Poles by the French Emperor Napoleon III.

On 9 January 1864, Wróblewski was seriously wounded near Rudka Korybutowa while covering the insurgents’ retreat. Peasants hid him in a barn and took him to the nearest manor house. The aunt of the future Nobel Prize winner Maria Skłodowska smuggled the half-dead partisan dressed as a woman through the Russian cordon. One of the officers noticed that the alleged maid’s face was covered in blood, but allowed them to continue on their way. Wróblewski may have been saved by the fact that, as a commander, he never allowed prisoners to be killed and let them go free. While the lieutenant-colonel was recuperating in Dzików at the home of the Tarnowski counts, Traugutt was arrested in Warsaw. The fight was over.

In April, Pelagia Zgliczyńska married Dąbrowski, who was awaiting sentencing. A few days after the ceremony, she too was imprisoned. In November, the court sentenced Dąbrowski to 15 years of hard labour in Nerchinsk, his wife was already sent to Nizhny Novgorod in June. Russian friends did not forget about the captain. When he reached Moscow on his way to Siberia, a basket was waiting for him in the prison canteen, with a woman’s outfit hidden under the plates. The convict changed his clothes, wrapped his head in a handkerchief and went out quietly with the servants.

Last barricade

Before winter had passed, the Dąbrowskis left Russia using false passports. Things were not going well for them in France. Jarosław’s health was failing, and in order to support his growing family he worked as a draftsman and cartographer. Wróblewski, sentenced in absentia to death by a Russian military court, lived in an attic cottage and fed on manna. Both dreamt of a revolution that would sweep away the order that had no room for a sovereign Poland. In their minds, they waged battles against the invaders and studied the press in search of heralds of the coming war.

The tsar’s agents, whose aim was to discredit the Polish refugees, were not idle either. They plotted the distribution of counterfeit Russian banknotes. Dąbrowski spent nine months in custody before he was acquitted. The affair harmed his efforts to win the leadership of the radical wing of the émigré movement. He was succeeded by Wróblewski, who was less controversial and more willing to compromise. On 1 February 1869, the lieutenant-colonel announced a manifesto: I do not believe in any other Poland than the one that our people will raise from the grave with their industrious hands; I do not wish for any other Poland than the one that, with the entirety of its historical borders, will give the entirety of civil rights to all its sons; I do not wish for any other Poland than the one where the rule of man over man will give way to the rule of the freedom of reason and law, where ignorance will disappear in the rays of universal education, and poverty – in the conscientious distribution of social benefits – I can neither live nor die for any other Poland.

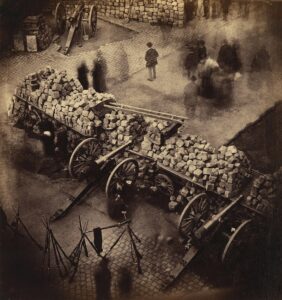

The political upheaval in Paris, which took place on 18 March 1871, found Dąbrowski in the south of France, where he wanted to join the army formed by his idol Garibaldi. He had already criticised the French government and sympathised with the opposition left. He knew many of the future revolutionaries personally. He wrote memoranda in which he argued that Paris, with its human and financial resources, could become an impregnable fortress. Meanwhile, the Commune was paralysed by bickering politicians giving conflicting orders to soldiers.

The moment when the government was virtually defenceless was missed. The failure of the offensive on Versailles in early April shook up the authorities of the revolutionary capital leading to a major personnel reshuffle and the Poles benefited from this. Dąbrowski was given command of the most vulnerable north-western section of the front. With counterattacks, he tried to push the government forces as far away from Paris as possible. But he had too few men, cannons and ammunition to win. He could only delay the advance of the enemy. After further regroupings, Wróblewski commanded the western front, and Dąbrowski became commander-in-chief. He was dismissed after four days, then reinstated when the outcome of the civil war was already determined.

Wróblewski, who spoke poor French, was for some time quartered at the Elysée Palace, in the suite where Tsar Alexander II had stayed during a recent visit to Paris. He did not tolerate drunkenness, thievery and lynching. He refused to carry out the order to blow up Notre-Dame Cathedral. When the situation became hopeless, Dąbrowski sent Pelagia and their three sons to London. Agents of Versailles offered him one and a half million francs for coming over to their side. This upset the general, and rumours of his betrayal made him decide to die honourably. On 23 May, he stormed the barricade at the junction of Myrrha and de Poissoniers on horseback leading a detachment of communards. Severely wounded in the abdomen, he was transferred to a nearby hospital. The last moments of Dąbrowski were witnessed by a Polish doctor. His body was buried the same night in a makeshift grave at the Père-Lachaise cemetery.

On the path to martyrdom

Wróblewski won several street battles, but on the night of 25–26 May, he advised his subordinates, who were still on their feet, to change into civilian clothes and disperse. In Paris, the hunt began for revolutionaries and Poles. Even those who stayed away from the Commune were arrested, beaten and killed without trial. Moved by the persecution, Jan Nepomucen Janowski complained in his poem ‘To the Polish leaders in the Paris uprising’ that ‘too carried away by their lust for imminent fame/ they mingled carelessly with a cause foreign to us’.

Wróblewski did not hide; on the contrary, he carelessly sat at the Café de la Régence, popular with émigrés. When he heard that he had to go to London, he replied: ‘I hear the climate there is ugly’. It was only in August that his compatriots almost managed to force him onto a train with a Prussian passport under the surname Woldemar. In Paris, he was sentenced to death in absentia, and the priest in the village of Walery’s mother cursed him speaking at the pulpit.

It is not known whether Wróblewski met Dąbrowski’s widow in London. Pelagia returned to Poland after several years, and worked as a French teacher in Jasło and Krakow. In her old age, she became a conservative. The best general of the Commune seemed a natural candidate for the leader of a future uprising. But it never broke out. France finally gave up its role as Poland’s advocate, opting instead for an alliance with the Russian Empire. The thought of giving up the armed struggle was alien to Wróblewski. In a country that is collapsing under the hideous yoke of foreign violence, I do not understand the work called organic: that is legal, that is compromise, that is in the spirit of the Targowica Confederation. I see only one path for the salvation of Poland – a sharp, martyr’s path, bloodied from the bottom up, he declared.

The general was attracted to women, but he never married. He probably thought he was too poor for that. People like him were considered an eternal threat to the status quo, which is why Wróblewski was constantly haunted by police agents and emissaries of European powers. Some wanted to know what he was up to, others wanted to take advantage of his enthusiasm. Politically, he joined the socialists, cooperated with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and took patronage of Józef Piłsudski’s pro-independence faction of the Polish Socialist Party.

He died on 5 August 1908. He had spent his last years in Ouarville, at the home of Henryk Gierszyński – a doctor who had witnessed the death of Dąbrowski. The general’s funeral was a political demonstration of the French left. The comrades funded a tomb at Père-Lachaise, bearing the dedication: ‘To the heroic son of Poland – the people of Paris’. Dąbrowski’s remains, previously moved to another Parisian cemetery, were lost.

Author: Wiesław Chełminiak

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki

Bibliography: Jarosław Dąbrowski by Jerzy Zdrada and Patriota bez paszportu by Jerzy W. Borejsza