On November Night, the lower classes of the Warsaw community joined the young cadets. According to Dr. Adam Buława, a historian from the Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw, some historians even use the term “the second Warsaw Uprising”, as the first was the April 1794 insurrection.

Polish Press Agency: One of the historians researching the genesis of the November Uprising stated that it was “a revolution without a revolutionary situation.” Why, then, on November Night, did a crowd of Warsaw residents march towards the Arsenal, and in the following days and weeks the society of the Kingdom of Poland became even more radicalized?

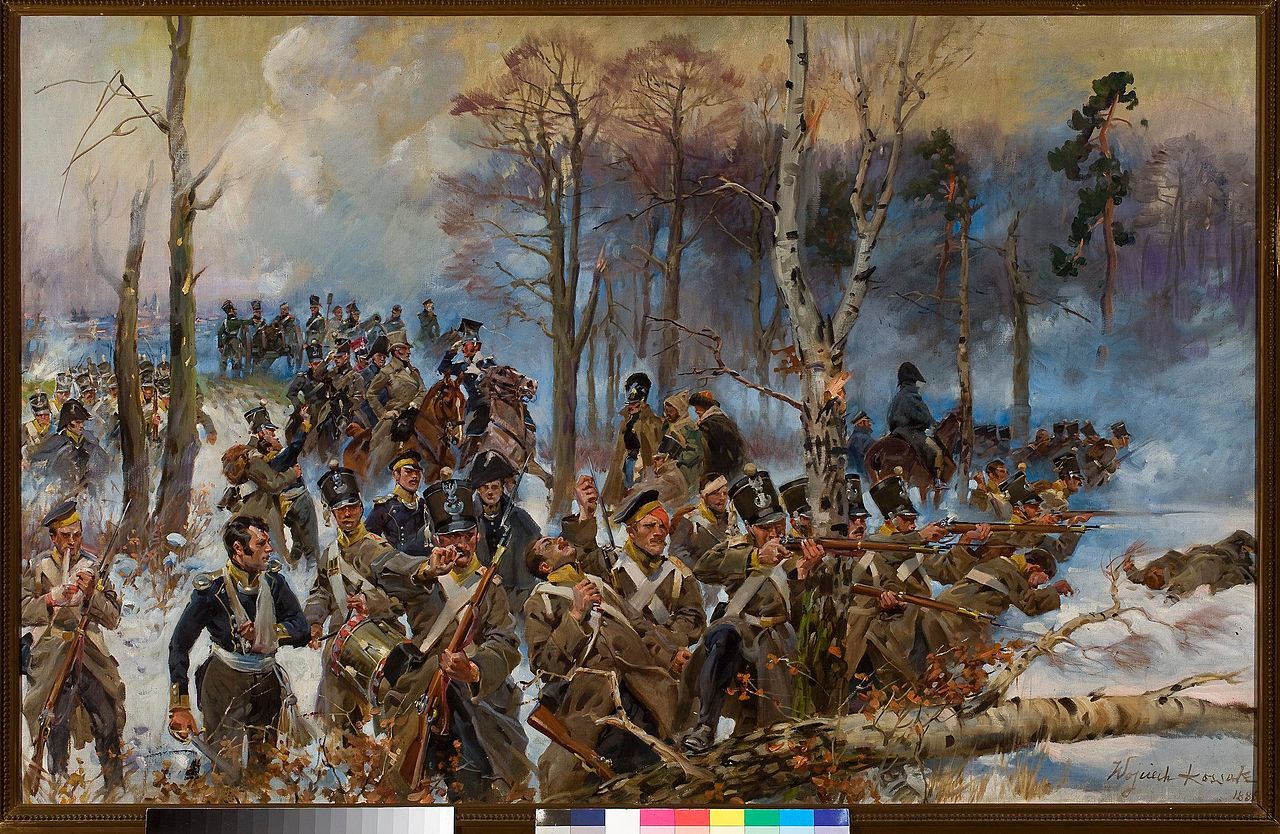

Dr. Adam Buława: The first two months of this independence uprising were described by one historian as a period of figuring out the uprising’s goals. Let us remember that the uprising was planned by a conspiracy of only a handful of people, mainly cadets gathered around Piotr Wysocki. They were in touch with the so-called elders of the nation, but this group saw no point in starting an uprising in the current political situation. Additionally, some of the senior officers considered the cadets’ actions to be a coup. That is why on the streets of Warsaw, on November Night, any generals who refused to join in or tried to talk them out of starting an uprising against the current political order were killed.

On November Night, the lower classes of the Warsaw community joined the young cadets. Some historians even use the term “the second Warsaw Uprising”, as the first was the April 1794 insurrection. The inhabitants of Warsaw, Wysocki’s cadets and the intellectuals supporting the rebellion had no plan for the uprising’s development. Their aim was only to start a movement after which they intended that more experienced politicians, specifically, those “elders of the nation,” would take over and lead them.

In December 1830 and January 1831, there were two opposing movements. The Princes Adam Jerzy Czartoryski and Franciszek Ksawery Drucki-Lubecki, also the Łubieński suite, i.e. the elite of the Kingdom of Poland, and many others, were trying to calm the situation. Their aim was to return to the political situation from before 29 November 1830 and “report” to the tsar about the restoration of peace in the Kingdom of Poland. At the same time, some concessions on the part of St. Petersburg were expected in return. Such hopes were expressed by many, including Drucki-Lubecki and MP Jan Jezierski, who were sent to the tsar by the dictator, General Józef Chłopicki, who also favored the “counter-revolutionary” group.

On the other hand, there were conspirators whose patriotic emotions, and will to fight the powers that were trampling on the rights of the [citizens of the] Kingdom of Poland, held sway over a large part of the society, not only in Warsaw, but also in the provinces. Both parties clashed in the political and propaganda arenas, as can be seen in the case of a dispute between Maurycy Mochnacki and Józef Chłopicki. Only when information about the failure of the Polish delegation’s talks with Tsar Nicholas I and the Russian demands for an unconditional surrender reached the Sejm, did most politicians succumb to the revolutionary mood. It was then that the Sejm deposed Nicholas I and the entire Romanov dynasty from the throne of Poland and the union with Russia was broken.

It can be said that this moment was one of the most important in the history of Polish parliamentarism. The deputies representing the nation acknowledged that they had the right to change the ruler when they were not fulfilling their obligations. In this way, they became de facto revolutionaries, just not in the sense of the French Revolution, of course. However, it was an act that completely changed the political reality and as a result of which [Poland] became a sovereign state. Between the end of January 1831 and the fall of the uprising, Poles enjoyed full sovereignty in a small area of the Kingdom of Poland for the only time in post-partition history.

Did this small country have any chance of survival thanks to a compromise with Russia or victories that might make Saint Petersburg decide that trying to keep control over the Kingdom of Poland was a useless endeavor? The defeat of the November Uprising is often blamed not so much on Russia’s superiority as on the procrastination of Polish commanders and politicians.

This is a path of alternative history, which leads us to consider events that never took place. However, many historians have followed this trail, including Jerzy Łojek in the book “Szanse Powstania Listopadowego: rozważania historyczne” (“Chances of the November Uprising: Historical Considerations”). The question is whether we could win the Polish-Russian war. Comparing the potential outcomes reveals that this was a confrontation between David and Goliath. However, at some point, the advantage of the Russian side was not so great on the Polish front or the front created later in the vicinity of Vilnius.

Even the Russians, despite their very experienced commanders, made huge mistakes. Perhaps if the Polish army had not been commanded by General Jan Skrzynecki, who was probably the worst choice for this position, the war would have lasted longer. In February 1831, when the Russians were crossing the borders of the Kingdom of Poland, they assumed that it would be a relatively easy and victorious march, smoothing the path before possible fighting in Western Europe. This situation is somewhat reminiscent of that of the summer of 1920, when the Bolsheviks assumed that they would easily take Poland and march to the West to carry the flame of the communist revolution there. In 1831, the Russians wanted to bring about a “counter-revolution.”

Meanwhile, in the Battle of Grochów, [Poland] achieved a draw, [a sure sign of] our victory, and then, when we were successful during the offensive on the Brest road, we practically had the Russians at our mercy. Breaking up the Guard and sending more forces to Lithuania could have brought success. Unfortunately, after the Battle of Ostrołęka on 26 May 1831, the uprising was on a downward trajectory, especially in the public consciousness. Nevertheless, the Russians assumed that the war would last until the spring of 1832. They went from one extreme to the other – from overly triumphant optimism to a pessimistic assessment of their strength and the alleged potential of the army of the Kingdom of Poland.

Yet it seems that [a conclusive] Polish military victory was not possible after all. The small population and economic potential of the Kingdom of Poland made it impossible to conduct a military campaign lasting more than a few months. However, political victory was a more realistic goal. We can refer to the examples of other nations fighting for independence at that time – the Belgians and the Greeks. The Greek cause was joined by Russia and the Western powers. At the conference table they established the scope of the independence of the new state, which initially covered a relatively small area. Perhaps it would be possible to refer to the Greek scenario, where the throne was taken by a representative of one of the German dynasties.

In the case of Belgium, there are even more similarities. Up to a certain point, Poles followed a political scenario much akin to the one in Belgium. The dethroning of the Romanov dynasty in Poland was a repetition of what had previously happened in Brussels against the House of Orange. The key to such a political success in Poland was an international conference of powers, which would maintain the autonomy of the Kingdom of Poland or strengthen it in relation to the Congress of Vienna.

Let us remember that the agreements of 1815 were interpreted in completely different ways by Poles and Russians. The latter believed that autonomy was the result of the benevolence of the Tsar-king Alexander and that Poles should treat instruments such as the Sejm and the constitution in a “commonsense” manner, that is, use them in a submissive way. Meanwhile, Poles hoped that this was only the beginning of more favorable changes and that, in the long run, the Kingdom of Poland would be merged with the rest of the Taken Lands, which were previously part of the First Polish Republic. The reason for convening an international conference could be the “sluggish pace” of the war and the defeat suffered by Marshal Ivan Paskiewicz and his possible successor. In such a situation, the Russians might be induced to give up representing the war as an internal affair of the empire, a rebellion of “ungrateful Poles”. This is probably the only realistic scenario of any victory for the November Uprising.

After its collapse, Polish émigré parties blamed each other for wasting opportunities. There was a belief that there were unused chances, including by failing to play many of the cards that [Poland] held, such as the peasant question or the attempt to reclaim the Taken Lands by sending stronger military supplies to the insurgents there. There were even more factors that could have contributed to a more favorable outcome of the uprising. Therefore, the defeat was particularly painful.

On the other hand, especially in exile, it was believed that any of these losses did not end the Polish struggle for the right to self-determination. They were continued in the spirit of the motto created in 1831: “For our freedom and yours.”

Interviewer: Michał Szukała (PAP)