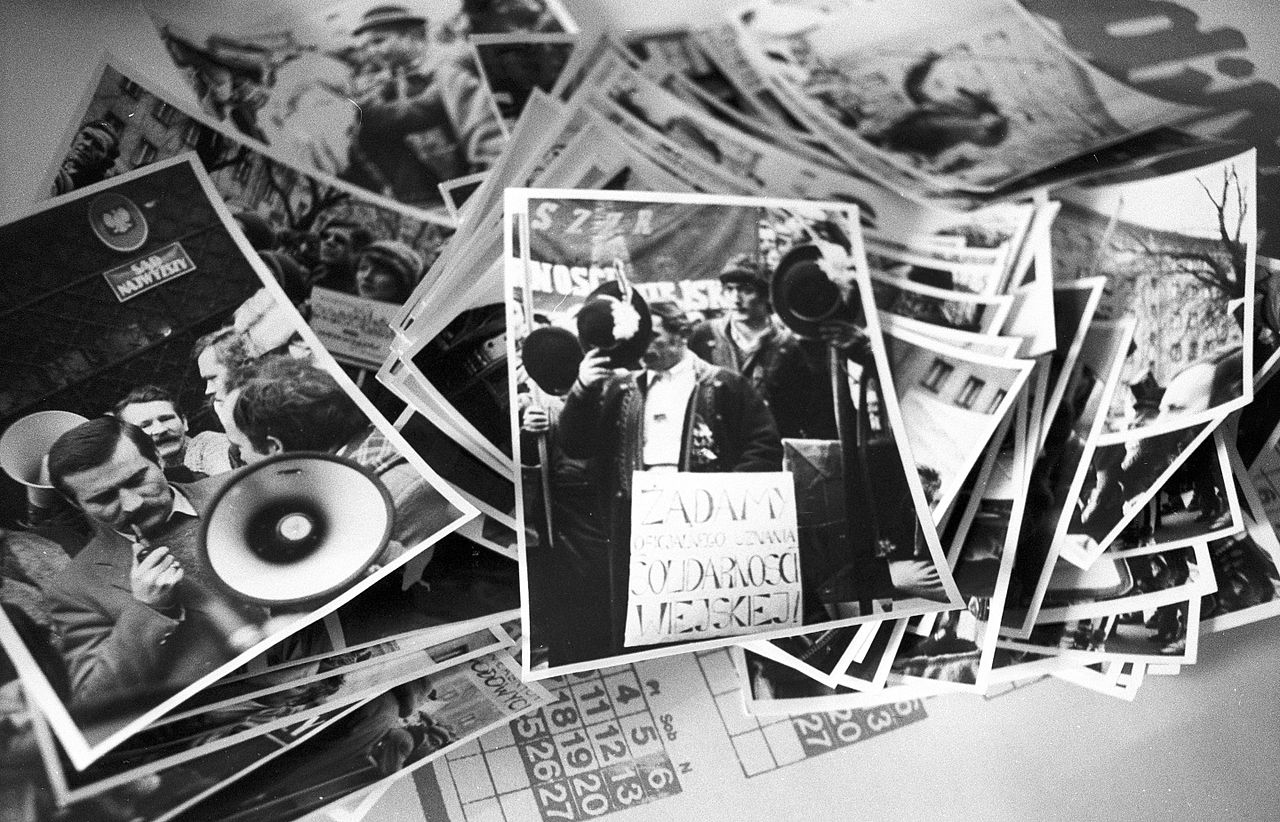

It was a breakthrough for the whole of Central and Eastern Europe. On 10 November 1980, Polish Supreme Court approved the legalization of the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union ‘Solidarity’. It was the first truly independent labor union in a Soviet bloc country.

by Tomasz Kozłowski

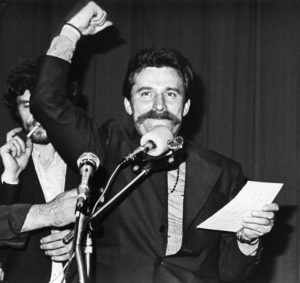

In the summer of 1980, the greatest wave of protests in history swept across Poland. By the time the crisis reached its climax, over 700,000 citizens were on strike. At a certain point, “the whole country” took part in it if we consider not the number of people, but their feelings – everyone waited for the outcome of the negotiations between the government and the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee. The committee, led by Lech Wałęsa, represented workers’ groups from the Tricity (Gdańsk, Gdynia and Sopot) and the surrounding area, a total of over 220,000 workers. They demanded most of all the right to organize trade unions. Wałęsa explained: “We are determined to make our last stand. If we don’t get it right now, we’ll never get it.”

The negotiations reached a stalemate. The authorities had already agreed to give a pay rise and grant an additional day off. However, when it came to this one issue – the establishment of trade unions – authorities refused to give in. Stanisław Kania, a high-ranking official of the communist party, who would be appointed the first secretary in two weeks, feared that “our consent to this demand would mean the creation of a power much bigger than the Sejm and national councils together.” He was right and the strikers knew it. Workers fought for unions because they feared that the communist party would withdraw its promises as soon as the protests died down. Therefore, they wanted to create an organization that would protect their interests.

The communist authorities found themselves in a hopeless situation. The whole country was protesting. The army and secret political police were not prepared to introduce martial law. Meanwhile, the Soviet army mobilized its divisions – the staff planned the operation of providing aid to the Polish army. However, the Soviets were also prepared in the event of a revolt by the Polish army. This worst scenario involved the appointment of an additional 100,000 reservists and keeping 15,000 war machines ready. The leadership of the Polish United Workers’ Party remembered the Soviet interventions in Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

Read more: Solidarity. The 40th anniversary of the birth of the social movement

The strikers won the war of nerves. The leadership of the communist party decided to give in. On 30 August, an agreement was signed with the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee operating in Szczecin, and a day later also with the one from Gdańsk. On 3 September – with striking miners in Jastrzębie, Silesia.

The whole country breathed a sigh of relief – even the authorities who had hoped to regain control of the situation. The signing of the agreement meant that the strikers attained their aim and they no longer had to worry about whether the party would decide to suppress the protests by force. The authorities – even though they gave in when it came to the trade union issue – also breathed a sigh of relief because after signing the agreement, the vast majority of plants returned to normal work and the specter of a general strike was averted. They hoped to somehow avoid fulfilling all requests of the strikers. However, on the day the agreement was signed, no one was aware that soon a trade union of several million would be established in Poland. The opposition activist Andrzej Krawczyk recalled: “This moment is forgotten today. The concept of establishing ‘Solidarity’ could be realized only two months later: at first it seemed that dozens of trade unions would be formed.” All over the country, people got organized. It was the greatest grassroots mobilization since the Second World War. Surprisingly, it was not only the authorities who preferred to deal with fragmented groups that sought to create many small organizations. The same vision of the movement was shared by the leaders of the Gdańsk strike led by Lech Wałęsa.

The key activists of the Gdańsk democratic opposition, who had belonged before August 1980 to the Free Trade Unions of the Coast, were convinced that their organization must remain regional. Lech Wałęsa, Andrzej Gwiazda, Joanna Gwiazda, Bogdan Borusewicz did not want to hear about any national connection. They feared that the creation of one nationwide organization would allow the authorities to manipulate the nascent social movement. To preserve its authenticity, they strove to create a loose, grassroots federation. However, they were alone in this. Lech Dymarski, who set up trade unions in Poznań, recalled: “[the] leaders of the Gdańsk strike were afraid that it would all fall on their heads (…). Their advisers supported this view. From the very beginning, they adopted a defensive position so as not to irritate the authorities.”

The strike at the Gdańsk Shipyard became legendary. When it finished, over a hundred delegates from all over the country came to the shipyard daily. They all asked for instructions and advice on how to establish unions in their workplaces. They talked about the harassment they suffered from the secret political police and local authorities. They asked Gdańsk to support the fight for their rights. Lech Wałęsa and other strike leaders could not remain deaf to these requests. On 17 September 1980, they had a meeting of delegates representing local trade unions. When all of them arrived, it turned out that they together represented almost 2 million workers.

Most of the delegates came to the meeting convinced that Gdańsk would take responsibility and assume the leadership of unions from all over the country. Karol Modzelewski, the opposition activist who represented the Wrocław union at the meeting, recalled: “We did not doubt at all that we were working on establishing a nationwide union. It was obvious to everyone, except for the inhabitants of Gdańsk. Was the Gdańsk Agreement regional, as the authorities wanted to interpret it? No way, it was nationwide! Therefore, the union should also be nationwide. It was convenient for the government to break the movement into industry or regional unions, because that would make its game easier.”

The meeting in Gdańsk had a dramatic course. Delegations from several regions agreed behind the scenes to push through the idea of creating a single union. However, the host was Lech Wałęsa, who imposed his vision and did not allow discussions on the new union statute. Ultimately, Jan Olszewski, an opposition activist and lawyer in political trials, spoke on this matter. He was supported by Karol Modzelewski, who was an extremely talented speaker: “Gdańsk won the strike for all of us, but it was won, which should not be forgotten, with strong support from all over Poland. Otherwise the strike would not happen [applause from the audience] and the Coast would commit suicide, if it cut itself off from Poland [applause from the audience]”. Under such pressure, Wałęsa had to give in. Later he recalled: “I was given [from my colleagues in Gdańsk] a bashing for this treason, for the fact that I entrusted the country to the leadership of this movement, and not Gdańsk.” One trade union was established, which took the name of the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union “Solidarity”. It was headed by the management – the National Coordination Commission – grouping representatives of all local organizations. Lech Wałęsa became the leader of “Solidarity”.

The name “Solidarity” meant that everyone acted hand in hand, nobody took care of their particular interests, ignoring the problems of others. For this reason, uniquely, the union was organized by regions, not different branches of industry. Otherwise the government would sooner communicate with representatives of the “strongest” professions (e.g. miners or shipbuilders), and ignore the “weaker” ones (teachers or health care workers).

Read more: Birth of Independent Free-governing Trade Union ‘Solidarity’: Behind the Scenes

The decision to unite all local groups was extremely important. However, the question of how strong the union was and whether it could really defend its members remained open. The structures were in the making, the authorities blocked the flow of information and tried to organize their own quasi-unions. Moreover, the situation in the country was still tense, not least because the government was reluctant to pay the pay rises negotiated during the August strikes. As a result, a wave of spontaneous protests swept across the country. It was a trial moment for “Solidarity”.

The leaders of “Solidarity” were aware that the authorities failed to meet financial obligations not out of their bad will. However, since the authorities did not pay the promised pay rise, dissatisfaction began to grow among the workers. Strikes broke out, which the leadership of “Solidarity” described as “wild” because they had not been consulted with the union. The workers’ groups and local unions demanded that Wałęsa took some steps and forced the authorities to pay. The leadership of “Solidarity” was pressured by workers and rank-and-file trade unionists to take action and Wałęsa could not oppose these demands. He explained that during the August strike, the country gave its support to the Coast, and now they expected repayment. Andrzej Gwiazda supported him: “We have to do what is beneficial to us, it cannot tell people not to ask for money while they are hungry.” Furthermore, rank and file members of the union were persecuted by the secret political police. In this situation, the leadership of “Solidarity” took a risk and announced preparations for a nationwide strike. Wałęsa argued: “The nation is determined. Even tanks won’t help the authorities. We will definitely win, although we will suffer losses, but we will win”. They were ready to go on a limb – nobody was able to predict what the reaction of the communist party would be.

During the preparations for the strike, the position of ordinary workers came to the fore: despite the lack of precise information (the authorities that controlled the media tried to conceal the news), the majority of them believed that if Gdańsk was ready to go on a strike, “it must have reasons for it”. The communist party was surprised by how great the country’s loyalty and discipline to the Gdańsk decisions were. The one-hour warning strike, carried out on 3 October 1980, turned out to be a success. One million three hundred thousand workers employed in 1,800 plants took part in it. Even in non-striking factories, flags were hung, sirens were turned on, and armbands were worn. It was a baptism of fire for “Solidarity” which managed to mobilize more people than took part in August 1980. The protest gave the workers a sense of strength. They gained a new identity and identified themselves as union members ever after. Solidarity was ready to fight for legalization.

It was not simple. The Regional Court in Warsaw was to decide about the registration of the union. The leaders of “Solidarity” submitted the relevant documents. However, the decision was not really made by the judge, but by the top leadership of the Communist Party. The first secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party, Stanisław Kania, did not want to allow the legalization of “Solidarity” in the proposed form. He was echoed by General Adam Krzysztoporski, the newly appointed Undersecretary of State in the Ministry of Internal Affairs, who for years worked in the Security Service, where he combated the democratic opposition. He explained what the judge should do: “examine the statute, propose amendments, if they do not agree, appeal to the Supreme Court.”

The judge stalled for time, asked for additional editing and changes to the submitted documents. Legal nuances related to the court procedure did not interest any of the rank and file trade unionists. There was an opinion that “the government stalled for time in this matter” and the authorities were “putting off the decision”. In many cities, there were posters not only on the walls, but on any free spot found. In Gdańsk, posters with a request for registration could be found at railway stations, bus stops, in electric railways, public transport, on buildings and in shops. In Szczecin one could read: “Whoever is against Solidarity, he is against working people and socialism.” Even some long-distance trains had flags and signs saying “We request registration.”

When the judge issued the decision on 24 October, it was consistent with what the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party had recommended. Solidarity was registered, but with imposed amendments! The judge, without the consent of the trade unionists, deleted the provisions concerning the right to strike from the statute and added a statement about the leading role of the Polish United Workers’ Party. The leadership of the Communist Party and the Ministry of the Interior began to prepare for a confrontation. General Adam Krzysztoporski noted that “the manner of registration, especially the court’s decision to supplement the statute, outraged the leaders of Solidarity.” The Ministry of the Interior was ready “in case of a confrontation”: it was planned, inter alia, to intern 30,000-40,000 people, close the border, and appoint several conscripts to the army.

As during the August strikes, the authorities did not feel ready to open confrontation. Wojciech Jaruzelski (who would become the first secretary of the communist party a year later and would finally introduce martial law) warned: “Martial law can only be declared in an extreme situation. It was not necessary, not even in the 1940s. Its introduction requires a guarantee that it will bring some effects. And is it possible to have the effects of martial law against millions of strikers? You have to be aware that such a decision cannot be abused”. The authorities had to surrender once again.

Read more: The Solidarity Revolution from the point of view of the KGB

Secret negotiations began, attended by representatives of the Politburo and the National Coordinating Commission, including Karol Modzelewski. During these talks, it was generally agreed what the Supreme Court should decide when it came to the registration of “Solidarity”. On 10 November 1980, the decision on the legalization of “Solidarity” was finally announced. It was a symbolic end to the formation of a new social movement. From that moment on, it took the form of a mass, legal and nationwide trade union recognized by the authorities.

It was an important event in the history of Solidarity, but it is not specially remembered. The August strikes and the signing of the agreement are still considered a symbolic moment of the union’s birth. Is it really the right moment to be remembered? The real nature of “Solidarity” was only shaped after the strikes had ended.

Author: Tomasz Kozłowski – PhD in political sciences, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin