The August strikes in 1980 were a breakthrough in the history of not only Poland but also of the world. The establishment of Solidarity initiated the collapse of the Communist system. However, it is also worth looking at Solidarity as an extraordinary phenomenon of social self-organization.

by Łukasz Kamiński

Poles had opposed Communism since its forced introduction in 1944. The underground army kept fighting for many years, however, after 1947 it was already very weak. At the same time, the only legal opposition party, the Polish People’s Party, was no longer independent. The first postwar wave of strikes and demonstrations had also declined. During the Stalinist period, the peasants’ resistance to collectivization and the Catholic Church’s attempt to maintain autonomy were of the greatest importance. The latter began weakening after the arrest of Primate Stefan Wyszyński in 1953.

In June 1956, residents of Poznań headed out to the streets to demand ”bread and freedom”. The bloody pacification of the protest did not calm things down. In the autumn, the upheaval spread all over Poland. The new leader of the Polish United Workers’ Party, Władysław Gomułka, was forced to make significant concessions. Stopping collectivization and the thaw in relations with the Church were of long-term importance, among others. Gomułka’s rule ended with the brutal pacification of the student protests in March 1968, an anti-Semitic campaign, participation in intervention in Czechoslovakia, and a bloody massacre of workers’ protests in December 1970. All those experiences would later prove to be significant for Solidarity and for its identity, and at the same time, as a tool to deprive Communist authorities of their legitimacy.

After a short period of economic prosperity at the beginning of the next decade, the economy was in crisis again. An attempt to institute a huge price increase in June 1976 led to further protests. The authorities withdrew their plans, but made it up to themselves later by launching a campaign of hatred against those participating in strikes and demonstrations, as well as by mass repressions. Many people stood up for the persecuted. The Workers’ Defense Committee was established, followed by a number of other opposition organizations, including the Free Trade Unions. In October 1978, Cardinal Karol Wojtyła was elected pope, taking the name of John Paul II. This gave Poles great hope, which was only strengthened during the pope’s pilgrimage to his homeland in June 1979.

The economic situation continued to deteriorate. In response to another increase in meat prices in July 1980, strikes broke out all over the country – most of them in the Lublin region. In order to end the strikes, the authorities made concessions – mainly by introducing higher wages, but in some cases also by guarantying safety to strike participants and by promising to organize new elections to work councils. The wave of protests declined after several weeks, and, feeling reassured, party leader Edward Gierek went on vacation to Crimea.

Meanwhile, on 14 August, a strike began at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk, this time due to dismissal of the Free Trade Unions activist Anna Walentynowicz. Other companies quickly joined the protest. After a few days, the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee was established, which prepared a list of 21 postulates. Shortly thereafter, a strike also began in Szczecin, where the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee announced a list of 36 demands. In both cases, the establishment of trade unions independent of the authorities came first. They also both requested the release of political prisoners, freedom of speech and religion, and made a number of economic demands.

Hundreds of factories belonged to both committees, and they became the actual center of power. For example, in Gdańsk, the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee introduced a ban on the sale of alcohol, which was observed in shops and hotels. Despite widespread shortages in supplies, strikers were provided with food, and farmers also joined in to help. Information about the protest reached the whole country thanks to broadcasts by Radio Free Europe and leaflets printed by striking workers. Interest in the events in Poland was growing day by day around the world.

The Communist authorities had no choice but to start negotiations. Government commissions headed by deputy prime ministers were sent to both cities. The strikers in Gdańsk were supported by experts – independent intellectuals. The main problem was the issue of trade unions – their establishment would mean questioning the foundations of the Communist system, in which everything is controlled by the party. However, when the strike also began in Wrocław and later in the mines in Upper Silesia, the authorities had to give up. An agreement was signed on 30 August in Szczecin, a day later in Gdańsk, and on 3 September in Jastrzębie-Zdrój.

New unions were being spontaneously established throughout the country. After only a few weeks, there were over 3 million members. The Communist authorities tried to limit the scope of the movement, which caused further strikes. Thus, they limited themselves to surveillance of new structures, propaganda attacks and attempts at destroying the unions from within. Practically from the very beginning there were plans to use force against the unions.

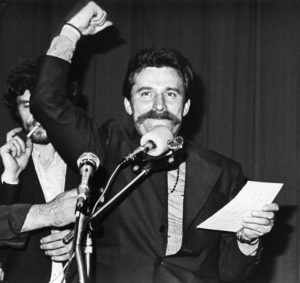

Meanwhile, on 17 September 1980, representatives of the committees from across Poland made a few key decisions. First of all, they decided to set up one trade union, not several, as some opposition activists proposed. They decided to name it after the strike bulletin from Gdańsk – ”Solidarity”. The word also reflected the unusual nature of the union, based on regional rather than industry structures. This choice meant that common issues were more important than the particular interests of individual professional groups. Lech Wałęsa, the leader of the Gdańsk Committee, became the head of the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union ”Solidarity”.

From the very beginning, the authorities tried to entangle the new movement in conflicts. The first of them was related to registration of the union in court. The union’s statute was amended, limiting the right to strike and recognizing the ”leadership role” of the Polish Workers’ Party. Only the threat of a general strike prompted the authorities to make concessions. Solidarity was registered on 10 November 1980. Another source of tension was the issue of political prisoners, in December 1980 a Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners was established.

Great importance was attached to the past. On 16 December 1980, in Gdansk, in the presence of tens of thousands of Solidarity representatives from around the country, the Monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers was unveiled, commemorating the victims of the December 1970 massacre. In June 1981, a similar monument was erected in Poznań, on the anniversary of the anti-communist uprising of 1956. History books and brochures were published, exhibitions and popular lectures were organized as part of the Union Universities that were being created throughout the country. The issues of Polish-Soviet relations (especially the Katyn Massacre of 1940), the history of post-war repression and social rebellions were the most popular.

Great attention was also paid to the Hungarian Revolution (1956) and the Prague Spring (1968). This was associated with fears that things might end in a similar way also in Poland – with Soviet intervention. Today we know that it was not planned, but back then it seemed very likely. These fears led to limiting the demands so as not to cross the invisible line. Jacek Kuroń called this attitude the ”self-limiting revolution”.

The failure to accomplish aims set by the social agreements saw 1981 begin with a dispute with the authorities. The problem of working on Saturdays was particularly important. Local conflicts also broke out in several regions, mainly related to the abuse of local party representatives. The increasing tension briefly interrupted the appointment of the new Prime Minister, General Wojciech Jaruzelski, who called for ”ninety peaceful days”.

Inspired by the freedom won by striking workers, other social groups also wanted to create their own organizations. The most important were the Independent Student Association and the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union of Individual Farmers ”Solidarity”. The authorities refused to legalize them for many months. They were forced to legalize the Independent Student Association in February 1981 after a long strike of students in Łódź. Farmers could establish their own organization after much more dramatic events.

In March 1981, Bydgoszcz police beat three Solidarity activists. This caused widespread outrage and a warning strike was carried out in which most Poles took part. A general strike was also announced in the absence of any concessions from the authorities. The maneuvers of the Warsaw Pact armies in Poland was another source of tension. Finally, Wałęsa canceled the strike just before it began. The authorities promised to register the Solidarity of farmers and punish those guilty for beating the protesters (which never happened). The cancellation of the strike caused a strong division in the leadership of the union – many thought that it could have forced the Communists to make further concessions. Society would prove itself unable to mobilize itself again on such a scale as it did then.

In the shadow of constant conflicts provoked by the authorities, Solidarity members were working hard on the union’s program, as well as dozens of reforms in virtually all areas of social life. They were prepared not only by trade unionists, but also people of culture, science, teachers etc. A characteristic feature of this time was great hope, a sense of unity, and a willingness to act for the common good. For several months, a real civil society existed in Communist Poland. Hot discussions took place in the magazines published by Solidarity. In addition to several weekly newspapers published in official circulation, the union printed nearly two thousand bulletins appearing outside censorship.

In May, the attack on John Paul II, widely regarded as the protector of Solidarity, and then the death of the Primate of Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński were a great shock for Poles. Supplies were decreasing, despite the introduction of a rationing of basic goods, which led in the summer of 1981 to numerous ”hunger marches” and other protests. It was widely suspected that this was the result of deliberate action by the authorities in order to exhaust the society.

Meanwhile, over 9.5 million Solidarity members (Poland had less than 36 million inhabitants at the time) chose almost 900 delegates for the union’s congress. It took place in Gdańsk, in two rounds in September and October 1981. The congress provoked a backlash of Communist propaganda, the Soviet media described it as an ”anti-socialist and anti-Soviet orgy.” The reason for this rage was above all the ”Message to working people of Eastern Europe”, which expressed the hope that similar organizations would be created in other countries of the Soviet bloc.

The congress chose new authorities (Wałęsa remained the chairman) and adopted the program. It was entitled ”Self-Governing Republic” and was a comprehensive proposal to reform the state, both in economic, social and political terms. It was a program of gradually building democracy and restoring the subjectivity of society.

However, there was no chance for its implementation. In October 1981, Jaruzelski became the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party, which accelerated plans to tackle Solidarity through the use of force . This was facilitated by increasing public fatigue with economic problems and constant political tension.

On the night of 12-13 December 1981, martial law was imposed, which stood even against the Communist law. The power was taken by the Military Council for National Salvation. Already on the first night, over 3,000 Solidarity activists and other organizations were imprisoned, in the following months nearly 10,000 people were detained in internment camps. Throughout the martial law, over 11,000 people were sentenced by court verdicts, the highest sentence was 10 years in prison. Strikes that broke out among the opposition were brutally pacified. The massacre in the ”Wujek” coal mine in Katowice where 9 miners were killed became a symbol.

Despite the imprisonment of most of the leaders, Solidarity survived in the underground. Secret factory committees operated throughout the country, and many new ones were established in various regions, then in April 1982 a national leadership was appointed – the Temporary Coordinating Committee. The union called for resistance – short strikes, and with time – also demonstrations. Unfortunately, even the largest of them did not bring any concessions from the authorities, but only new victims. This happened with the demonstrations on 31 August 1982, organized in 66 cities. Six people were killed, hundreds were injured, and thousands were arrested.

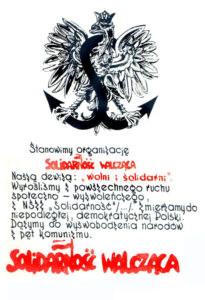

In this situation, Solidarity focused on building the ”Underground Society”. It consisted of unions, a wide movement of independent culture, science and education, underground publications – hundreds of independent magazines were published, as well as books and brochures. There were even underground radio stations broadcasting short programs from self-constructed transmitters. In addition to unions, new organizations were formed: the radical Fighting Solidarity (1982), Federation of Fighting Youth (1984), pacifist and ecological Movement Freedom and Peace (1985) and many others. The hopes of Poles were maintained by two subsequent visits of John Paul II – in 1983 and 1987. The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Lech Wałęsa (1983) was also a great support.

Martial law was formally abolished in July 1983. However, this did not end the repressions, political trials continued and people died during the demonstrations. There were also political killings. The most famous was the kidnapping and murder of Solidarity chaplain, Jerzy Popiełuszko in October 1984. The agitation was then so great that the authorities decided to punish the perpetrators.

The chronic economic crisis, ongoing repression and lack of hope for change caused a breakdown of social mood, which made the underground functioning difficult. In 1986, the authorities tried to take advantage of this situation by declaring the release of political prisoners and calling for the cessation of independent activities. However, only the two waves of strikes in 1988 forced them to make real concessions. In exchange for the ending of the second one, a part of Solidarity, centered around Wałęsa, was offered a chance to begin round table talks. This offer intensified the long-standing divisions in the opposition and the union itself.

The round table talks finally began in February 1989 and lasted two months. Both sides agreed on the re-legalization of Solidarity, the appointment of the office of president, free elections to the newly appointed Senate and partly (35%) free elections to the Sejm (lower chamber of the parliament). The adopted agreement was to guarantee the maintenance of power by the Communists. The result was much different. The Poles treated the June 4 election as a plebiscite that rejected the continued existence of the Communist system. The Polish Workers’ Party managed to make parliament elect Jaruzelski for president, but their attempt to form a government was unsuccessful. Tadeusz Mazowiecki, the editor-in-chief of Tygodnik Solidarność, became the new prime minister.

Poland was on the path towards democracy and market economy. The Solidarity struggle also opened the way to freedom for other Eastern Bloc countries. This victory, as well as the symbolic ”umbrella” over difficult reforms, had its own price. Solidarity never returned to the strength and significance of 1980-1981. That extraordinary period of Polish history, however, still remains a source of inspiration – and not only for Poles.

Author: Dr. Łukasz Kamiński – the President of the Platform of European Memory and Conscience and former President of the Institute of National Remembrance from 2011 to 2016.

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin