If you look into it carefully, the lens that is the classifieds of the time of the Nazi occupation, acquires bloody veins – as if it were not a tool made of cool glass, but a lens.

by Wojciech Stanisławski

What can we do? We live. We live lives, which means we reside somewhere, we eat, sleep, and work. And there are various problems in this life, someone steals a ‘lady’s cherry-coloured bicycle, in good condition’, someone loses their light brown dachshund. But if you are wealthier, you can buy a house or a plot of land, if you are less wealthy, you can at least buy a gabardine coat. If only work can be found – there will be something for a ‘carpenter school graduate, familiar with office work’, for a dress cutter, and a housekeeper able to cook well. And then you can also think about finding your second half, for example, a ‘forester with beautiful qualities of the spirit’.

Author: Sebastian Piątkowski

Publisher: Pilecki Institute, 2021

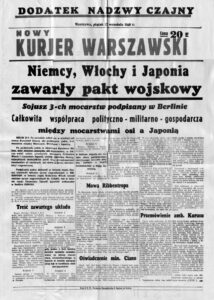

A formula that is becoming a thing of the past (by the way, who is going to write something about Poles on the basis of ads posted on OLX, a local incarnation of e-Bay?), classifieds in newspapers prove to be a phenomenal historical source, allowing us to reproduce patterns of behaviour, values, but also the entire fabric of everyday life. This may be especially true in times of dramatic political and censorship oppression: there is no parliament, state or theatre, the press and school are operating in limited form, but you need to buy coal for the winter, there is a demand for razor blades, so ads are published in rags and are not subject to any interference (apart from censorship, of course). Sebastian Piątkowski, the author of the work reconstructing the daily life of Poles in the General Government, on the basis of such adverts, compares the sixth column of the Nowy Kurier Warszawski (and local rags, such as Gazeta Radomska) to a lens focusing on and showing researchers phenomena that escape even diarists and conspirators.

Reading this panorama of life in the antebellum, which covers a spectrum of everyday concerns, from the search for home and work, to philately and the removal of corns, is an extraordinary experience. What strikes at first, of course, is the power of the human need for stability, building perhaps on smoke from the chimney. ‘A great nation, an undefeated nation, an ironic nation / (…) / Lounges in the markets, communicates in jest, / Trades in old doorknobs stolen in the ruins.’ – noted wryly a Nobel Literary Prize laureate, Czesław Miłosz, about this phenomenon Let us add: it offers the best perm liquids and ‘root substitutes’, converts and fashions ‘old hats into a la new ones’, steals conveyor belts from mills for shoe soles, and sews cloaks made of blankets. The endurance of forms, which are now but empty shells, can either make you feel delighted or angry, or most likely – astonished: the sky over the country collapsed, but a 22-year-old blonde ‘with a tender heart, full of understanding for suffering, loneliness and sadness, simultaneously full of life and verve, loving music, singing, dancing, cinema, and everything beautiful (…) wants to meet a man of similar qualities’ (she must have wanted a lot, considering that the price per word oscillated around 0.20 zlotys). The aprons of soubrettes rustle, drugstore salesmen and hairdressers recommend their services – the world is like in an old cinema, Biedermeier on ration-card marmalade and pomace oil.

The most striking, however, is how the ‘lens’, if you examine it carefully, becomes infested with bloody veins – as if it were not an instrument made of cool glass, but a lens. Naturally, the classifieds of the Nazi occupation period do not mention striped uniforms or incendiary bombs, mouth plaster or gas cans. There are no political allusions or any references to conspiracy either – although underground gunsmiths were likely leafing through the columns of ads looking for potassium chlorate sold on favourable terms, we also know that the ads were sometimes used as ciphers.

There is the calling, frantic and futile (‘Does anyone know anything about my wife Janina, my sons Zygmunt, Januszek and Edmus Andrzejewski? A husband is asking for news’) of exiles from the territories incorporated into the Reich, September 1939 refugees, and Katyn widows, still looking for their husbands in the autumn of 1940. An eight-month-old baby is lost during the bombing of a railway station, in a crib tied with a crimson ribbon. There are advertisements as to which it is not clear whether their author should be admired more for her art of speaking in hushed tones, or for the beauty with which she carries her head in the face of almost inevitable death: ‘A dark-haired woman with big black eyes wishes to only marry a Pole’ (Gazeta Lwowska, September 1942 – a month earlier 50,000 inhabitants of the Lviv ghetto were taken to the death camp in Belzec). And there are those that are everything at once – a cry, an epitaph and a medallion with a withered hair strand, such as this ad from Gazeta Radomska of December 1944: ‘Number 3 Stalowa St in Praga! Who knows about the fate of Anna Woskowiec, known as Niusia (…), whose balcony overlooked 11 Listopada St, a pale blonde, 28 years old, eight months’ pregnant, leaving for a walk with a small, white fox terrier?’

The original of the review appeared in the Sieci weekly no 26 (448), 28 June 2021

Author: Wojciech Stanisławski

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki