The life of Zawisza is shrouded in mystery. However, the few surviving sources allow us to conclude that he earned his legend honestly.

Modest beginnings

Zawisza’s father, Mikołaj from Garbów, came from middle knighthood. He held the position of Master of the Horse in the Land of Sieradz. This type of official had the task of managing royal studs and stables. Virtually no information has survived about his mother, Dorota. The Sulim family was not yet famous or wealthy at that time, so source accounts are extremely scarce.

Zawisza had two brothers – Piotr Kruczek and Jan Farurej, who was the youngest of the three. The older knights from Garbów were likely distinguished by their dark hair colour, as indicated by their nicknames Kruczek (little raven) and Czarny (black). In historical sources, Zawisza appeared for the first time precisely in the company of his siblings. A document from 1397 stated that Piotr Kruczek was selling part of the village of Siedlec to Jan Tarnowski, and the Zawisza brothers and Jan would not create any difficulties in taking over the said property. The aforementioned record allows historians to speculate that Zawisza had been born between 1370 and 1380.

A knight

At the core of Zawisza’s legend were his successes on the battlefields and in tournaments. From the late 1390s, the knight was likely in the service of Moravian margrave Prokop. This nobleman came into a major conflict with the Bishop of Olomouc, who threatened to excommunicate Prokop and all of his supporters. A document from 1399 mentioned that, among the knights listed was a ‘Swarch de Wissch’, whom researchers identify precisely as Zawisza Czarny.

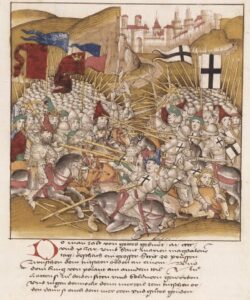

The Hungarian monarch Sigismund of Luxembourg eventually became involved in the dispute. As a result, Prokop was imprisoned in 1402. Everything appears to suggest that Zawisza then went over to the side of the victor. Indeed, the chronicler Jan Długosz wrote that the Polish knight was in the service of the Hungarian ruler between 1403 and 1408. Zawisza took part in the armed expedition of Sigismund of Luxembourg to Bosnia. However, following the outbreak of the Polish-Teutonic war in 1409, he returned to Poland, considering service to Władysław Jagiełło a priority. At the Battle of Grunwald, he took part in the ranks of the so-called ‘pre-chivalry’, i.e. the most experienced warriors fighting in the first line. Zawisza must therefore have had a reputation as an excellent knight at the time. His service with Sigismund of Luxemburg must have already been rich in military successes, since he was among the elite of knighthood at the time of the Battle of Grunwald.

The first mention of Zawisza’s participation in a tournament dates from 1412. At that time, a peace treaty was signed between Poland and Hungary. Enjoying the respect of both Sigismund of Luxemburg and Władysław Jagiełło, Zawisza was chosen as one of the witnesses to this momentous event. In June, the two rulers met in Buda, where a great tournament was held on the occasion. For two days, a hundred knights competed from morning till evening. Jan Długosz enumerated that representatives of Greece, Italy, Bohemia, Austria, France, Russia and many other countries took part in the battles. Of course, there were Poles there as well, including Zawisza Czarny and his brother Jan Farurej, Mikołaj Powała of Taczów, Dobiesław of Oleśnica or Jan of Kobylany. Długosz emphasised the valour of the Polish knights, but the victory went to a competitor from Silesia.

In 1415, Zawisza had the opportunity to fight a duel in Perpignan on the Mediterranean Sea. A lavish celebration was then held on the occasion of a meeting between Sigismund of Luxembourg and Ferdinand, ruler of Aragon. During the battle, the Polish knight blew the hitherto undefeated John of Aragon out of the saddle. Unfortunately, no more sources on the tournament struggles of Poland’s most famous knight have survived. His experience and fame, however, indicate that he competed many more times.

A diplomat

Zawisza did not base his career solely on his fighting skills. Loyal and charismatic, the knight quickly wormed his way into the favour of the King of Hungary and Poland. He repeatedly shuttled between courts in the role of a trusted diplomat. The period of the Polish-Teutonic war, when Sigismund of Luxembourg sided with the Order, must have been particularly busy for him. The knight’s efforts certainly contributed to the peace between Poland and Hungary in 1412.

In 1414, in turn, Zawisza was among the envoys selected by Jagiełło for the Council of Constance. Among other things, the delegation was to safeguard Polish interests in the dispute with the Teutonic Knights, whose Order enjoyed great popularity in the West. Even two years before the Council, the king of France threatened Jagiełło that he would declare war on Poland if the latter did not maintain peace with the Teutonic Knights.

Zawisza particularly distinguished himself in the later phase of the Council, in the famous case of the so-called arguments of John of Falkenberg. This Dominican monk sided with the Order in the Polish-Teutonic conflict, describing Władysław Jagiełło as a heretic. Pope Martin V listened to the Polish envoys, but made no firm decision on the matter and forbade any further speeches. Jagiełło’s envoys were outraged. They broke down the door at the pope’s palace and forced him to accept the appeal. Zawisza Czarny and Janusz of Tuliszków even stated that they would ‘defend their view with word, deed, hands and mouth’. The behaviour of the Polish knights was considered outrageous, but they were saved from consequences by the presence of a mediator, Sigismund of Luxembourg. Ultimately, Falkenberg’s arguments were condemned, and their author imprisoned.

A landowner

Zawisza’s military and political activities allowed him to amass a considerable fortune. Although the knight never entered the elite of the Polish Kingdom (as he did not hold a land office), numerous endowments compensated him for the hardships of warfare and frequent travels. From King Władysław Jagiełło, Zawisza received the starosties of Kruszwica and Spisz, to which several towns and numerous villages belonged. The knight also owned part of the family estate. However, it was not impressive and included allotments in only a few villages.

Zawisza’s career gained momentum during the Council of Constance. Even before his departure, Jagiełło gave him the dizzying sum of 800 grzywnas (for a few, one could buy a horse; the penalty for killing a knight was 60 grzywnas). Rich in cash, Zawisza began to expand his domain, buying more land. He also held land granted in Hungary, although more modest than in Poland.

The final battle

In 1427, Sigismund of Luxembourg began preparations for an expedition against the Turks. On the king’s instructions, Zawisza began recruiting enlisted soldiers. In the spring of 1428, Sigismund’s army besieged the Danube fortress of Golubac. However, upon hearing of the approaching Turkish reinforcements, the Hungarian ruler entered into negotiations and began withdrawing troops to the other side of the Danube. The Turks, however, did not keep their word and launched an attack during the crossing. The retreat was covered by Zawisza Czarny and would be his last battle.

It is not certain whether he died during the battle or was taken prisoner first to later die in captivity. This is what Sigismund of Luxembourg wrote to Lithuanian Prince Vytautas: ‘In Zawisza, the knighthood has lost a most skilful and most gallant companion and leader. As the whole world knows, he was the bravest knight, the most experienced warrior, and a great diplomat’.

Author: Antoni Olbrychski

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki