There are actually few composers active in the 20th century who can be referred to as ‘contemporary classics’. Witold Lutosławski certainly belongs to this narrow group. An artist who, confronting the key issues of the 20th-century art of composition, created pieces that impress with their balance of intellect and emotion, and are simultaneously extremely open to listeners taking the trouble to appreciate music contemporary to them. He regarded his talent, his ability to compose, as an ‘entrusted good’ to be returned to society in the form of finished works. Subordinated to this goal, Lutosławski’s oeuvres remain as emblematic for Polish music of the second half of the 20th century as that of Karol Szymanowski for the first half.

by Iwona Lindstedt

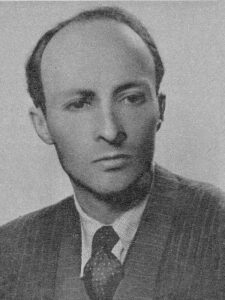

The Lutosławski family nest was an estate in Drozdowo, near Łomża. Born on 25 January 1913, Witold spent the first years of his life there, and in 1915 – fleeing from the front – his family moved to Moscow. There, the father and uncle of the future composer were engaged in pro-independence activities and for this, as ‘enemies of the Bolshevik authorities’, they were arrested in 1918 on the orders of Felix Dzerzhinsky, and subsequently executed without trial. Witold’s mother returned to Poland and settled in Warsaw, together with her children. It was at this time that Lutosławski took up systematic music studies – first piano and violin, and from 1927 theory and composition under Witold Maliszewski, a distinguished teacher. It was also at this time that Lutosławski’s first public performance of a piece, the now lost Dance of the Chimera for piano (1930), took place. After passing his high school exams in 1931, Lutosławski took up Mathematics at the University of Warsaw, which he interrupted after two years and – deciding to devote himself entirely to music – entered the Warsaw Conservatory. Although Maliszewski officially only taught classes in musical forms and counterpoint there at the time, Lutosławski regarded him as his only professor of composition.

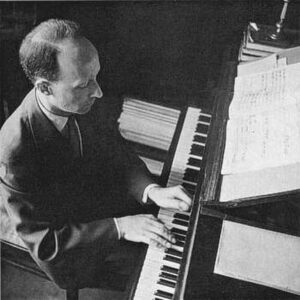

After graduating in 1937 with a degree in piano and composition, he did a year of military service at the cadet school in Zegrze. His intense return to creative work, which culminated in the completion of the Symphonic Variations and their premiere under Grzegorz Fitelberg, was disrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War. During the campaign of September 1939, he served as a radio operator. He was taken prisoner, but luckily managed to escape and return to Warsaw. There he earned his living first as an accompanist of barbershop music harmonists, and then as a pianist performing in a duo with Andrzej Panufnik in Warsaw cafés. Their repertoire included arrangements of many classical compositions, as well as quasi-jazz improvisations, but only one of Lutosławski’s works, Variations on a Theme of Paganini for Two Pianos (1941), played most frequently to this day, has survived.

Lutosławski spent the duration of the Warsaw Rising in the suburban town of Komorów, and when he returned to the ruined capital in 1945, he became involved in activities related to the reconstruction of Polish musical life – he took a job as head of the classical music department on the radio, and became the secretary and treasurer of the newly established Polish Composers’ Union. He also returned to creative activities. The main goal was to complete Symphony No. 1, which he had begun composing as early as 1941. This piece – despite its initial good reception – was soon criticised for not conforming to the criteria of socialist realist correctness imposed on Polish art during the Stalinist period. Thus, in order to survive the difficult times, Lutosławski then created works based on folk inspirations, as well as music of a utilitarian nature, including for film, theatre, and children’s songs. The artistic pinnacle of Lutosławski’s work during this period is marked by a virtuoso symphonic composition based on folk themes – the Concerto for Orchestra (1954). To this day, it is likely the most frequently performed of all of Lutosławski’s works.

Despite the enormous pressure exerted on artists by the authorities, Lutosławski worked hard in the late 1940s and early 1950s to formulate his own new musical language. It was not until 1958 that he revealed the results of these experiments in Five Songs to words by Kazimiera Iłłakowiczówna and in Funeral Music for string orchestra (with a dedication ‘à la mémoire de Béla Bartók’), in which he used consonances and series of twelve different sounds, arranged in such a carefully thought-out way that they could affect their sound colour and expressive value. This work not only marked a major breakthrough in his oeuvre, but also paved the way to a global career and financial stability thanks to an increasing number of prestigious commissions. However, before this happened – which had for years been a guarded secret – he composed light music for profit. Under the pseudonym of ‘Derwid’, registered with the ZAiKS (Society of Authors and Stage Composers) in 1957, he composed over thirty dance songs – foxtrots, tangos, slow foxes and waltzes – until 1963.

When Lutosławski presented Jeux vénitiens for orchestra in 1961, it became clear that he had added yet another innovative technique to his musical language resources. It grew out of the idea of enabling performers to perform their parts (in ensemble playing) more freely, without looking at others, which Lutosławski termed ‘controlled aleatorism’ or ‘ad libitum playing’. The sonic results of using this technique were extraordinary – creating both dense and shimmering masses of sound. The composer himself spoke of this using a figurative comparison:

‘Imagine that a painter, wishing to create a moving colour composition, fences off a certain area of free space. He divides this space into certain fields with fences and, between these fences, lets in some small animals, let’s say rabbits, painting them in different colours; placing rabbits of one colour in each field. They are in constant motion. So there is a vibration of the different colours. But the colours do not intermingle. The plane divided by the fences thus creates a composition in accordance with the painter’s intentions. The same happens in music’ (Lutosławski, The Power of Sound Imagination).

In his compositions, these ad libitum episodes were juxtaposed by Lutosławski with fragments played traditionally and led by a conductor. This allowed him to appropriately shape the expressive character of his works and consciously control the attention of the listeners, keeping in mind the basic laws of human perception, of which similarity and contrast play a key role. He therefore contrasted more and less important episodes, with the more essential ones gaining importance as the composition developed, leading to a single, expressive climax.

The combination of thinking about harmony and form, built on the above principles, was used in a number of Lutosławski’s most famous works, which consistently built up his reputation as a leading European composer and, at the same time, the informal leader of the so-called Polish school of composition – a conventional rather than established phenomenon, but one recognised by music critics as something distinct from the mainstream musical avant-garde of the 1960s and 1970s. These include, for example, Trois poèmes d’Henri Michaux (1963), String Quartet (1964), Symphony No. 2 (1967) and Livre pour orchestre (1968), as well as Concerto for cello and orchestra (1970), Les espaces du sommeil for baritone with orchestra to words by Robert Desnos (1975), or the orchestral Mi-parti (1976). The premiere of Trois poèmes launched Lutosławski’s career as a conductor, who from then on regularly conducted performances of his own oeuvres. His work on the aleatoric String Quartet, however, necessitated the introduction of a clever notational solution. Since the composer wished to avoid producing a conventional score that would suggest to performers the synchronisation of the quartet’s individual instrumental voices, the composer’s wife (it was she who generally transcribed his works by preparing carbon paper used as printing blocks) came up with the idea of placing the voices in frames and only then arranging them one above the other, as was customary in a music score.

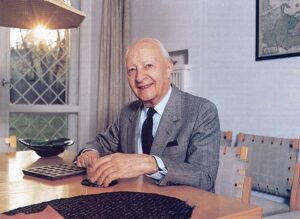

At the turn of the 1980s, Lutosławski’s attention was preoccupied by another idea – a composition method allowing for what the composer referred to as ‘thin textures’ for exposing the melodic dimension of his works, in other words, an expressive melody with accompaniment. The composer made use of this idea, and simultaneously synthesised his achievements in works written during the final decade of his life. These were commissioned by eminent artists, ensembles and institutions, and include Symphony No. 3 (1983), commissioned by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Chain II, subtitled Dialogue for Violin and Orchestra (1985), commissioned by Paul Sacher; Piano Concerto (1987), composed for Krystian Zimmermann; the charming song cycle Chantefleurs et Chantefables (1990), written without a specific commission; and Symphony No. 4 (1992), full of tuneful, melodic phrases. On the other hand, the measure of Lutosławski’s recognition in international musical circles became numerous distinctions, such as honorary doctorates from the universities of Chicago, Glasgow and Cambridge, honorary membership of the International Society for Contemporary Music, or the Polar Music Prize and the Kyoto Prize.

At the same time, Lutosławski maintained a clear presence in the home environment throughout. Since becoming involved in the activities of the Polish Composers’ Union, he held a number of responsible positions in this association over the years, similarly as in the organisation of successive editions of the Warsaw Autumn Festival inaugurated in 1956. With the exception of the period of martial law declared in Poland in December 1981, he did not shy away from public life – in 1989 he joined the activities of the Civic Committee under Lech Wałęsa, and in 1992, sat on the Cultural Council under the President. For many years, he was involved in discreet but intense charity work – he funded scholarships for young composers and performers, and only he and his family knew that he gave financial support to the seriously ill.

The last piece Lutosławski worked on was the Violin Concerto – unfinished due to the composer’s sudden illness and death on 7 February 1994. His departure was felt with great intensity by the musical world as the end of a certain era in the history of the 20th-century art of composition, marked by turbulent stylistic and aesthetic transformations. Lutosławski himself felt an heir of the part of it that emphasised the combination of technical excellence with an outstanding sensitivity to the sensual and emotional impact of music. And although, as he said, his aim was not so much to win over listeners as to discover them among those who ‘feel the same way’, he certainly managed to convince many of them that contemporary music was worth listening to. He proved that – to use the words of Joseph Conrad whom Lutosławski was fond of quoting – the ‘magical suggestiveness of music, which is the highest form of art’ works regardless of the type of musical language used.

Author: Prof. Iwona Lindstedt – Professor at the Institute of Musicology, University of Warsaw

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki