From the spring of 1942, in the territory of the General Government (GG), German policy towards the Jewish population entered a phase of mass deportations to extermination centres. These actions, carried out under the code name ‘Operation Reinhardt’, aimed at the extermination of all Jews in the GG area. Among the few who escaped deportation and sought refuge on the so-called Aryan side were the Goldmans from Łańcut. For humanitarian reasons, the spouses Wiktoria and Józef Ulma from the village of Markowa decided to help Jews seeking shelter. They and their children paid the highest price for their decision.

by Martyna Grądzka-Rejak

Before the war

On 7 July 1935, the wedding of Wiktoria née Niemczak and Józef Ulma took place at the parish church of St Dorothy in Markowa. The Mass was celebrated by the then vicar, Father Józef Przybylski, and the best man and maid of honour were Antonina Szylar and Antoni Szpytma. After the church ceremony, a wedding reception was held at the Niemczaks’ home. According to local tradition, so important to the young couple, the bride and groom personally invited guests to the wedding and reception. A few weeks before the planned date, they visited family and friends for this purpose. The nuptials were celebrated for at least two days. The Ulmas’ wedding has been immortalised in a photograph. It shows the couple in festive attire, surrounded by dozens of guests, posing against the backdrop of the cottage. The photographs taken later by Józef Ulma, who was fascinated by photography, would accompany them throughout their lives, until the tragic end of their life together. They would also become an extraordinary source of knowledge about what it had been like.

Wiktoria and Józef had met long before they began a family. They were twelve years apart in age. He was born on 2 March 1900, the son of Martin and Franciszka née Kluz. He came from a poor family and had three siblings. Wiktora, on the other hand, was born on 10 December 1912 into the large family of Jan and Franciszka née Homa. At the age of six she lost her mother. Franciszek, Wiktoria’s brother, was friends with Józef Ulma, so as neighbours and mates they would visit one another. This, among other things, gave the youngsters the opportunity to get to know each other and deepen their acquaintance. They were both believers. They graduated from primary school in Markowa. However, due to the age difference between them, they did not attend it at the same time. In 1929, Józef enrolled at an agricultural school in Pilsen to later complete it with very good grades.

They both lived in the village of Markowa, which lay in the Lwów voivodship in the inter-war period, but today is located in the Podkarpacie voivodship. The village was founded in the second half of the 14th century; German settlers were then brought there. Over time, the village became increasingly Polish; its population also increased. The local government introduced there in the second half of the 19th century, as well as the giving of land to the inhabitants for ownership, significantly influenced the development of Markowa. It is also worth noting that, from the early 20th century, the greatest political influence in the village, and to some extent in the region, was exerted by peasant groups: the Polish People’s Party ‘Piast’, and later the Polish People’s Party. The Union of Rural Youth of the Republic of Poland ‘Wici’ was also of great importance. At the time when Wiktoria and Józef were leading their conscious adult lives, Markowa had a population of almost 4,500. It was therefore a large place, also considered to be well organised and prosperous.

Both Wiktoria and Józef were involved in the local structures of the Union of Rural Youth of the Republic of Poland ‘Wici’. Józef was active there, among other things as a librarian and a passionate photographer. He was also involved in activities of an artistic nature. He played one of the leading roles in the play Kordian and the Boor based on the novel by Leon Kruczkowski. Through his involvement in the Union, he came into conflict with the parish priest of Markowa, Father Władysław Tryczyński, for whom the ideas propagated by ‘Wici’ were too liberal and communist. Wiktoria was also involved in local initiatives, she was a member of the Amateur Theatre Group in Markowa; she played the role of the Virgin Mary in a nativity play.

Nearby, in the village of Gać, situated about 5 km from Markowa, was the People’s University established in 1933. Its head was Ignacy Solarz, a well-known populist and educational activist at the time. Józef Ulma often met with him and discussed social issues. The university carried out educational activities in various fields, including the modernisation of daily life in the Polish countryside. By 1939, 14 courses had been held in Gać, attended by more than 500 young men and women, including Józef and Wiktoria. The education gained there and at the schools attended before, combined with the constant pursuit of passions and interests, meant that Józef excelled as a farmer in his home village. He specialised in growing vegetables and fruit, as well as in beekeeping. He organised a fruit tree nursery and was involved in grafting apple trees, among other things. He was also unique in that he raised silkworms and mulberry trees. This element of his activity further attracted the interest of the local authorities and elite. Part of Józef Ulma’s private library has survived, which, in addition to religious books, included such works as The Electrical Engineering Handbook, The Photography Handbook, Nature and Technology, The Geographical Atlas, The Dictionary of Foreign Words and The Use of Wind in Economy. This last title in particular shows how progressive he was. He himself constructed a small wind power plant, thanks to which he was the first in the village to light his house partly by means of electricity. Today, visitors to Markowa are bound to notice that there are many wind turbines producing electricity in the surrounding area.

The participation of local youth in the courses of the aforementioned university, as well as a number of other grassroots initiatives carried out in Markowa, such as the preparation and publication of the newspaper entitled Kobieta wiejska (Village woman) since 1939, meant that a group of people with progressive and pro-social views was growing in Markowa, and the Ulmas were among them. All this also made Markowa stand out from other towns in the region.

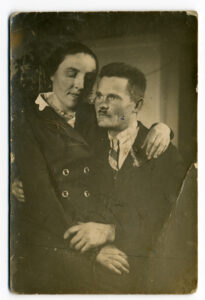

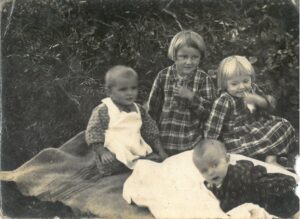

After marrying, Wiktoria and Józef’s life continued to revolve around farming and everyday matters and initiatives in the village of Markowa. Together they ran a small farm, their small house was located on the outskirts of the village. Józef, in addition to his daily chores, continued to be passionate about photography and farming, and was also involved in community affairs. Wiktoria, on the other hand, devoted herself fully to running the house and taking care of the children. And their family increased in number every year. Stanisława was born first on 18 July 1936. A year later, on 6 October 1937, their second daughter Barbara arrived. On 5 December 1938, their first son Władysław was born. Already during the German occupation, on 3 April 1940, another son Franciszek came, followed by Antoni born on 6 June 1941, and Maria born on 16 September 1942. The surviving photographs show Wiktoria performing various chores around the house and farm. Many of the photographs show the children smiling, at play or with family members and neighbours. There are also joint photographs of the couple embracing one another. One photograph catches the eye in particular, that of Wiktoria Ulma bending over a piece of paper and studying with her eldest daughter Stanisława. Education was important in the lives of both spouses, and they wanted to pass these values on to their children.

Legislation and politics under German occupation

The outbreak of the Second World War and German occupation did not remain without influence on the functioning of the inhabitants of Markowa, including the Ulma family living there. The rural population was subjected to compulsory quotas. From 1942 onwards, failure to deliver them was punishable by death. This had the effect of lowering food rations. The ubiquitous terror, the obligation to observe a curfew, the fear of being deported for forced labour within the Reich or of being conscripted into the Building Service (Baudienst), were all part of everyday wartime life. Firstly, Poles displaced from the so-called lands incorporated into the Reich and, from 1943 onwards, Polish refugees from the east, seeking rescue from the Ukrainian nationalists, were sent to the villages. This affected the housing and provisioning possibilities in the village.

In turn, from the spring of 1942, in the face of German Holocaust policy, Jews, including those residing in and around Markowa, were faced with extremely difficult choices in terms of survival strategies. The vast majority complied with the occupier’s announcements and perished during Operation Reinhardt at one of three extermination centres (Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka). To this day, there is no known data about the number of ghetto escapees to the so-called Aryan side. One important factor determining the behaviour of the Polish population towards Jews seeking refuge was the occupation legislation. Of key importance was the third ordinance on restrictions concerning a stay in the General Government of 15 October 1941, which introduced the death penalty for helping the Jewish population. Not only did it uphold the order for the isolation of Jews, but it also introduced a provision that was decisive for Polish-Jewish relations in the GG. Among other things, it stated that ‘Jews who leave their designated district without authorisation are subject to the death penalty. Persons who knowingly provide such Jews with a hiding place shall be subject to the same punishment. Instigators and helpers are subject to the same punishment as the perpetrator, an attempted act will be punished as an accomplished act.’ In November 1941, the German police authorities issued a ‘shooting order’ (Schießbefehl), which obliged police officers, including those from the ‘Blue Police’, to shoot dead without trial all Jews found outside the ghetto without permission. This also applied to women and children.

It is worth noting that Jews had been living in Markowa during the pre-war period. Compared to the community as a whole, this was not a large group. According to the 1921 census, 126 people of Jewish faith lived there. In the entire Przeworsk district, where the village was located, most of them lived in towns, and about two per cent were Jews inhabiting the countryside. Historians estimate that, just before the outbreak of the Second World War, there were between 20 and 30 Jewish families in Markowa, i.e. approx. 120 people. They had prayer houses located in the village, while the nearest synagogue was in Łańcut. Their settlement in the village was not compact, their houses stood among Polish ones. They were predominantly engaged in trade, with several involved in farming. It is difficult to determine exactly how the contacts between Wiktoria, Józef and the Jewish inhabitants of Markowa proceeded. Taking into account the fact that they had bought agricultural produce, livestock and brought industrial products to the village, it should be assumed that they had at least maintained commercial relations.

On the other hand, during the occupation period, there were ca. 20 Jewish families living in Markowa, with a total of approx. 1,000 Jews in the district. From the beginning of August 1942, most of the Jews from Łańcut and the surrounding villages, including Markowa, were deported and murdered at the extermination centre in Belzec, while those unable to be transported were shot on the spot. From August onwards, there was a ‘hunt’ for those in hiding, who attempted to wait out the ongoing extermination campaign in the region in the forests and fields. The enforcement of the aforementioned ordinances concerned mainly rural areas. Following the liquidation of successive ghettos, special pursuit groups (composed, among others, of German gendarmes, the SS and ‘Blue’ policemen) were sent into the field to ‘track down’ Jewish fugitives and those who had tried to shelter them. It was not uncommon for Poles caught red-handed in such a ‘crime’ to be shot on the spot (including entire families), to have their property looted and destroyed, to be brutally beaten, or to be brought before German special or summary courts. Information about such incidents spread throughout the area and heightened the fear of those with whom the Jews were sheltering. The local occupation authorities, including, for example, the ‘Blue Police’, also used such incidents to discourage the local population from aiding Jews.

A crime at dawn

In light of the available sources, it is not entirely clear when the Jews seeking help arrived at the Ulmas’ house located on the outskirts of Markowa. They were: Saul Goldman, a local well-known pre-war cattle trader, and his four sons of unknown names (in Łańcut they were called the Shalls). The Ulmas offered them shelter in the attic. After some time, two daughters and a granddaughter of Chaim Goldman from Markowa also joined the people in hiding: Lea Didner with a daughter of unknown name and Genia (Gołda) Grünfeld. It is worth mentioning that the Goldmans had previously been assisted for a fee by Włodzimierz Leś, an officer of the ‘Blue Police’, who lived near Łańcut. After some time, not only did he refuse further support, but equally to return to them their stored property. Most likely, at the end of 1942, the abovementioned Jews found their way to the Ulmas.

They stayed in the attic of Wiktoria and Józef’s small house. They spent most of their time outside the hiding place, participating in daily life and farm work. The men helped with tanning leather or chopping firewood. One photograph taken during such work by Józef Ulma has survived. The women, in turn, helped Wiktoria with the housework. As she had been pregnant since mid-1943, any help was important to her. They hid when outsiders came to the house, or when the situation was considered as becoming dangerous and there was a risk of denunciation. Joseph took photographs for Kennkartes, among other things, so it was relatively common for various people to visit his farm. However, while it was possible to keep secret what went on at the Ulmas’ house and farmyard, it was definitely more difficult to conceal, for example, the larger food purchases made by Wiktoria. This aroused curiosity and generated questions, and, in a relatively small community, rumours spread quickly. Nevertheless, the Jews stayed with them for more than a year.

At dawn on 24 March 1944, a punitive expedition consisting of five German gendarmes from the Łańcut post arrived at the Ulmas’ home: Eilert Dieken (head of the German gendarmerie in Łańcut), Joseph Kokot, Michael Dziewulski, Erich Wilde and Gustaw Unbehend, as well as four ‘Blue’ policemen, including Włodzimierz Leś and Eustachy Kolman. They knew perfectly well where they were going and why, having received a tip-off about the Jews in hiding. The ‘Blue Police’ surrounded the Ulmas’ house, and the German gendarmes led the victims out one by one: they were then shot in front of the house. The Jews were murdered first, followed by the Ulma couple, and finally the underage children were executed. Their corpses were buried on the farm; the bodies of the Jews were thrown into one pit, the bodies of the Polish family into another. The Ulmas’ house was ransacked and the gendarmes took all their valuables.

The news of the crime committed against the Ulmas and their children, as well as against the Jews hiding with them, spread very quickly through Markowa and its surroundings. It was the period before Easter, and people gathered in front of the church and talked about these events. It was a huge tragedy for the entire village. A particular burden and dilemma was felt by those with whom other Jews were still in hiding. Historians estimate that 21 Jews were saved in Markowa, including the Weltz family (Aron, his wife, two children and three relatives), who had been hiding in the attic of Dorota and Antoni Szylar’s house for several months. However, there are discrepancies as to how many Jews died at the hands of Poles in Markowa since the summer of 1942. According to one testimony, that of Jehuda Ehrlich, the day after the murder of the Ulmas, over 20 bodies of murdered Jews who had previously been hiding with Poles were found in fields surrounding the village.

Not long after this crime, the villagers secretly placed the Ulmas’ corpses in makeshift coffins and buried them again. Shortly after the war, their remains were moved to the parish cemetery in Markowa. In the autumn of 1947, the bodies of the murdered Jews were exhumed and moved to the Cemetery of Victims of Nazism in Jagiełło-Niechciałki.

Several weeks after the crime in Markowa, a ‘Blue’ policeman from the Łańcut police station, Włodzimierz Leś, was found guilty of denunciation by the Polish underground and shot dead on 10 September 1944 in accordance with a sentence of the Polish Underground State.

***

The massacre of the Ulma family from Markowa became, in a sense, a symbol of the German repression of Poles helping Jews during the Second World War. In 1995, Józef and Wiktoria Ulma were posthumously awarded the title of ‘Righteous Among the Nations’ by the Yad Vashem Institute in Jerusalem. In 2010, the Ulmas were awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Order of Rebirth of Poland by the President of the Republic of Poland. In turn, the Ulma Family Museum of Poles Saving Jews during the Second World War in Markowa opened in 2016. Since 2018, on the anniversary of the tragic events there, 24 March has been observed as the National Day of Remembrance of Poles Saving Jews under German Occupation. In September 2003, the beatification process of the Ulma family began, with its finale taking place in Markowa on Sunday, 10 September 2023. The uniqueness of this event lies in the fact that the process concerns not only the spouses, but also their offspring, including an unborn child.

Author: Martyna Grądzka-Rejak – PhD, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki