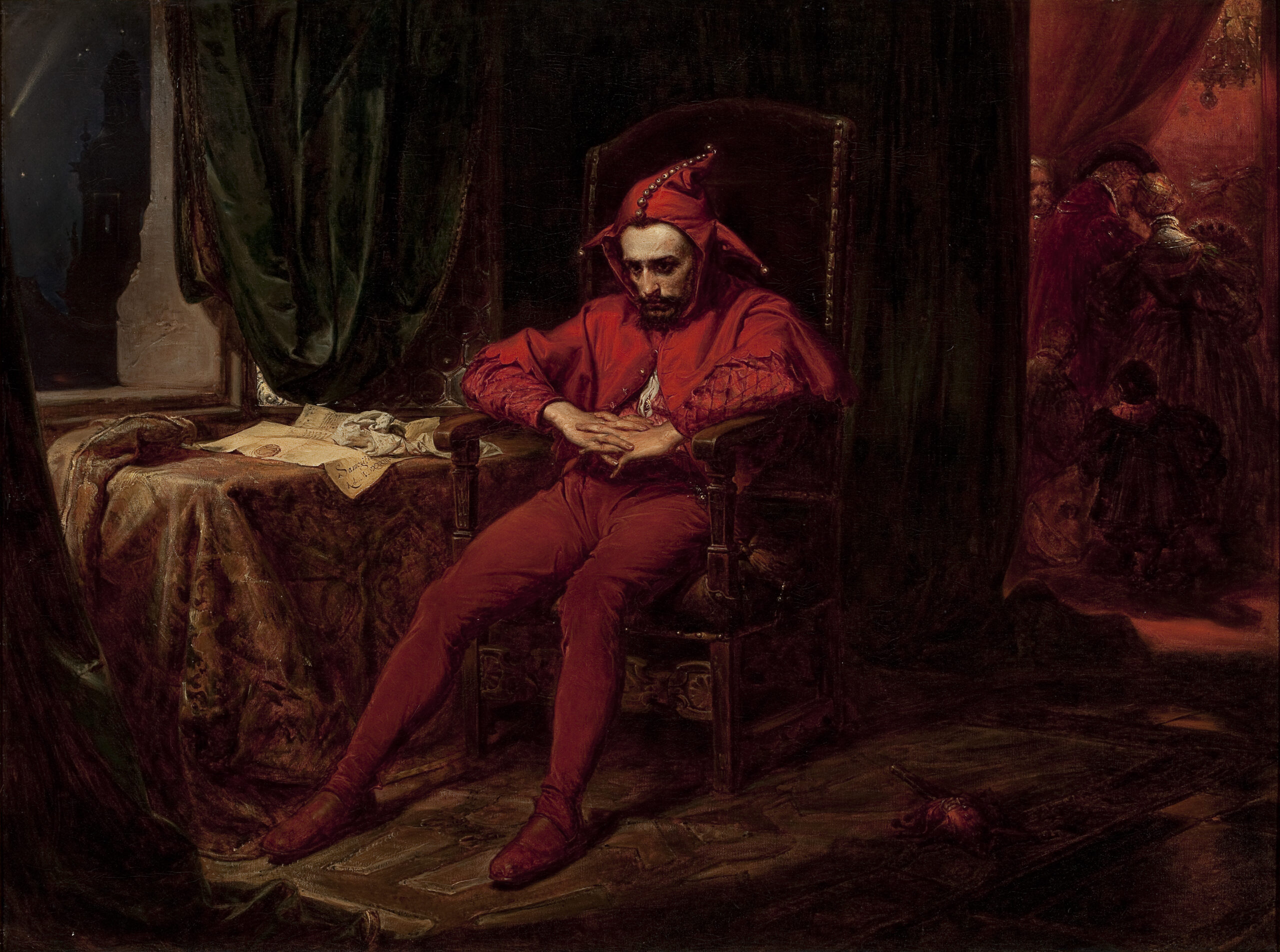

At the court of Queen Bona Sforza, the party is in full swing. The royal jester is the only one to see the approaching disaster…

by Michał Haake

Jesters bring pleasure, jokes, fun and laughter to others, ‘as if this is what the grace of God sent them here for, to cheer up the sorrow of human life,’ wrote Erasmus of Rotterdam.

Histrion, jokester, funnyman, clown, merrymaker, buffoon, gagger, jester, and gusman were among the names given in medieval and Renaissance Poland to people whose regular occupation was to entertain others. History remembers by name mainly court jesters: Wacław entertained Władysław Jagiełło, Prince Witold (Vytautas) was amused by Henne, Bieniasz made sure King Jan Olbracht had a good laugh, elderly Hanusz and the jester called Doktor worked at the court of Sigismund I the Old, while Sigismund II Augustus employed one named Sebastian.

They wore yellow, white or red coats with a hood, also known as a kukla. This jester’s cap had a pointed tip, also called a horn, with which the jester defended the truth, sometimes facing the King himself, and ears, sometimes pointed, sometimes hanging like a donkey’s, often topped with bells, the sound of which signalled the arrival of someone who did not belong to the ordinary courtiers. The jester’s attribute was a walking stick, called a flail because it was used to thrash vices. It was sometimes topped with a ball or a satirical fool’s face, which the jester directed towards his interlocutors so they could see themselves reflected in it as if in a mirror.

Later, it was Stańczyk, another jester of Sigismund I the Old, who enjoyed the greatest fame. His contemporary, the poet Klemens Janicki, called him Morosophuse, meaning a wise man hidden under the mask of a jester. Another Renaissance poet, Mikołaj Rej, lamented that there were ‘no more such Stańczyks’, who would ‘weed out hypocrisy, that wretched weed, and throw the sacred truth before people’s eyes’. In the 19th century, Józef Ignacy Kraszewski recalled Stańczyk as ‘a jokester who not only entertained’, who ‘dressed in jocular garb, was always meant to not so much laugh as speak the bitter truth’. Historians from the ‘Cracovian school’, whose views Matejko took into account, celebrated Stańczyk as someone who, in his time, ‘was the only one to see the wrong and openly proclaim it’, as ‘a symbol of truth in politics and the study of history’, setting him as an example for all those concerned about the fate of Poland.

A masterpiece by a 24-year-old painter

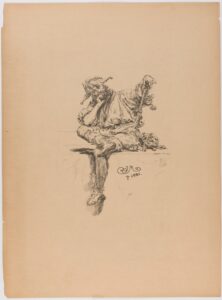

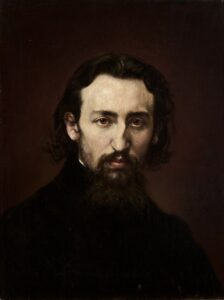

The young Jan Matejko was among those fascinated by Stańczyk. He was impressed by the cleverness of the jester, which he demonstrated when he wanted to prove that the world’s largest population are physicians. Pretending to have a toothache, Stańczyk received advice from every passer-by he met, which he meticulously noted down, and later presented their list as proof of his claim. Matejko’s painting depicting this scene was created in 1855. It shows Stańczyk still in his yellow coat, which the artist had picked up from one of the miniatures in Baltasar Behem’s Renaissance codex. Perhaps Matejko was already asking himself at the time whether he could match Stańczyk’s sharpness of mind. Seven years later, he gave Stańczyk’s face his own features, painting him sitting in contemplation during a ball at the court of Queen Bona Sforza. The question that needs to be asked is: How should this gesture by the artist be understood?

The full original title of the painting was Stańczyk during a ball at the court of Queen Bona in the face of the loss of Smolensk, but it was forgotten over time. What was remembered was that it was about ‘the loss of Smolensk’, with the addition that a ‘card’ or a letter lying on the table contained such news. This contributed to the fact that, even not long ago, Matejko had been reproached for his distortion of historical facts. For if he depicted Stańczyk lamenting the loss of Smolensk, that is in 1514, he could not simultaneously have introduced him to Queen Bona Sforza, who did not arrive in Krakow until four years later. And it was concluded that Matejko was unable to focus on the meticulous checking of historical data at the time as he was suffering from the rejection of his marriage proposal to Teodora Giebułtowska. In the pensive and sad Stańczyk, therefore, one should see the alter ego of the pained artist, and thus the explanation why the figure bears his features. But why should a heartbroken Matejko feel a communion with Stańczyk depressed by the loss of Smolensk? Fortunately, this question does not need to be discussed, as the inscription Sammogitia A.D. MCXXXIII (i.e. Samogitia in 1533 A.D.) is clearly visible on the documents on the table, attesting that Stańczyk was depicted almost twenty years after the capture of Smolensk by the Muscovite army.

Matejko may have thought that, even then, Stańczyk was still in great pain over the loss of the fortress. Marcin Bielski, the second most highly regarded Polish historian besides Jan Długosz, noted that, in 1533, a notable hunt took place, during which Stańczyk was attacked by a bear and then stripped of his clothes by the peasants who rescued him from his oppression. King Sigismund I is said to have mocked the jester, saying, ‘Thou hast conceived thyself not as a knight, but as a jester, that thou hast fled from the bear’, at the same time ‘pitying him for having been stripped’, but Stańczyk retorted: ‘You, my King, have been stripped more than myself, most notably of Smolensk, and yet thou art silent’. One may believe, then, that the King is enjoying himself in the painting, and neglecting the affairs of state, to the growing annoyance of Stańczyk.

However, this is not what emerges from the image. Immediately after the description of the hunt, Bielski gave two pieces of information: 1. that in summer ‘a comet was burning for a long time in the north, which was considered harmful to the northern countries’, and 2. that the King sent a message to Vasili, a Muscovite prince, ‘to return Smolensk if he wanted stable and eternal peace’, and when he refused, the King began preparing for war. The King thus has some right to rejoice in the hope of a successful settlement of the war. As a counterbalance to the ballroom scene, however, Matejko imagined, visible through the window, the aforementioned comet of 1533, a harbinger of ‘harm’. Thus, the seriousness painted on Stańczyk’s face appears to stem from a premonition that the King’s war efforts would be in vain.

The information about the preparations for war by the Polish king was elaborated upon by Bielski, who stated: ‘Therefore, it was drawing closer to the war (…) and a tax on soldiers per hide was permitted there in Lithuania for three years at twelve groszes .’ This information takes the reader back to 1534, when the Vilnius Sejm approved the taxes in February. Perhaps Matejko also takes the viewer beyond the year 1533 by placing the name ‘Samogitia’ on the card lying on the table. The course of the mobilisation of the common army for war announced the following year was affected by the rebellion of the Samogitian nobility against the commander-in-chief Janusz Radziwiłł, and the helplessness of the Polish king in resolving the conflict, which weakened the military capabilities of the Polish-Lithuanian side, and ultimately prevented the recapture of Smolensk. It cannot be ruled out that Matejko had also heard about this, although it is now difficult to identify a written source for this knowledge.

Sitting in the castle chambers, the jester looks neither at the comet, nor at the documents on the table, and not at the carefree courtiers either. The jester’s staff lies on the carpet. The face adorning this sceptre, a head carved in wood, represents stupidity. Stańczyk would stick it on a daily basis in front of the noses of those he criticised. Perhaps the sceptre lies there because the fool’s face adorning it pokes its tongue out at the carefree courtiers. Stańczyk himself is lost in thought. If the aforementioned elements refer to the daily work of a jester and approximate historical events from the time of the wars with Moscow, the deeply pensive Stańczyk appears to transcend that historical situation; distinguished from the entire surroundings by the red of his costume, he seems to persist in such a temporal dimension in which it is possible for the artist to identify with him.

Stańczyk with Matejko’s face

Matejko did not want to create the illusion that he had moved back in time by imagining he was Stańczyk. What differed from this historical figure was that he had full knowledge of the totality of the historical incident; he knew that the wars with Moscow had not led to the recapture of the Smolensk fortress. By giving Stańczyk his own features, Matejko evoked him as a model for thinking about history. Matejko’s Stańczyk remembers the loss of Smolensk in 1514 and, in the context of this past, reflects on the present in 1533. Twenty years of wars that did not lead to the recapture of Smolensk became a source of Stańczyk’s fears about the success of the following attempt, a cause to reflect on the reasons for these failures, an incentive to undertake critical reflection on the history of the state. In the same way, Matejko would conceive of the tasks of historical painting, treating his works as an answer to the question of why Poland lost its independence.

Matejko decided that he would start ‘from the wounds’. It is likely that, while he was still working on Stańczyk, the painter received photographs of five people who had died in 1861 in Warsaw in anti-czar demonstrations. He then set to work on the monumental piece of Skarga’s Sermon. This painting, depicting a Jesuit speaking to King Sigismund III and the Polish elite, was a reminder that the threats perceived by Skarga had not been taken into account, leading to Poland’s weakening and, in time, collapse.

The figure of Stańczyk will return in Matejko’s work in the painting The Prussian Homage (1882). This is also when Matejko gives him his own features. The characteristic broken nose leaves no room for doubt. What worries Stańczyk this time around, now that the Polish-Teutonic wars have come to an end, the Grand Master Albrecht Hohenzollern must humble himself before the Polish king, and the monastic state is transformed into the secular Ducal Prussia dependent on Poland? By endowing Stańczyk with his own features, Matejko encourages the viewer to take into account all that is known about that history today, hence also the role of Sigismund II Augustus, who changed the provisions of the treaties. Stańczyk literally carries him on his shoulders and presents him to us. Sigismund II Augustus raises his hand in the likeness of his father’s outstretched hand. His gesture, however, already signifies something different, as it is a change in attitude towards Albrecht. Previously, the agreement stated that Ducal Prussia would go under Polish rule as soon as the line of male descendants of Albrecht and his brothers ceased to exist. Sigismund II Augustus, however, allowed the Hohenzollern line of Brandenburg to take over the rule of Ducal Prussia. Later, Prussia emerged from the Hohenzollern-ruled state, participating in the partitions of Poland.

The figure of Stańczyk returned in one of the paintings-sketches from ‘The History of Civilisation in Poland’ series, painted in the years 1888–1889. In the painting The Golden Age of Literature in the 16th Century, the painter depicted Stańczyk alongside the figure of Michał Sędziwoj, an alchemist famous throughout Europe for possessing a powder (tincture) that made it possible to convert molten lead or silver into gold.

The 16th century was not only the ‘golden age of literature’. It can rightly be called a moment in history – Wacław Szymanowski stated in the mid-19th century – in which alchemy had the greatest impact on the minds… the lust for riches was the key motive for indulging in these practices; in a palace or a cottage, in a poor craftsman’s house or the house of a rich townsman, you can encounter crucibles, fireworks everywhere… In Matejko’s painting, the alchemist lifts a silver coin ‘transformed’ into gold. However, Stańczyk looks away, not wanting to touch it or have anything to do with pseudo-science. He turns to the viewer so that he also may see this glitzy face of the golden age.

Read also: Jan Matejko: The Painter of Polish History