‘What Can Poland Do? Questions Concerning the International Significance of the Polish–Soviet War and its Outcome in 1920’ is an article by Professor Andrzej Nowak lifted from the book titled The Polish Victory of 1920 published by the Polish History Museum.

by Andrzej Nowak

‘In mainstream Polish historiography, the period of the First World War is perceived in a way that may be called an overestimation of Poland’s subjectivity […]. The fact that Poland regained independence in 1918 is idealised. Actually, it can be interpreted mostly as a result of Germany’s victory over Russia, combined with a limited power of the German state to subordinate the territories won from the Russian Empire effectively, in line with German ambitions. […] That moment, which was above all a result of the fight between the powers over Central Europe, is now presented in Polish popular historiography mainly as the result of a causative action of Polish elites and the nation inspired by them.’

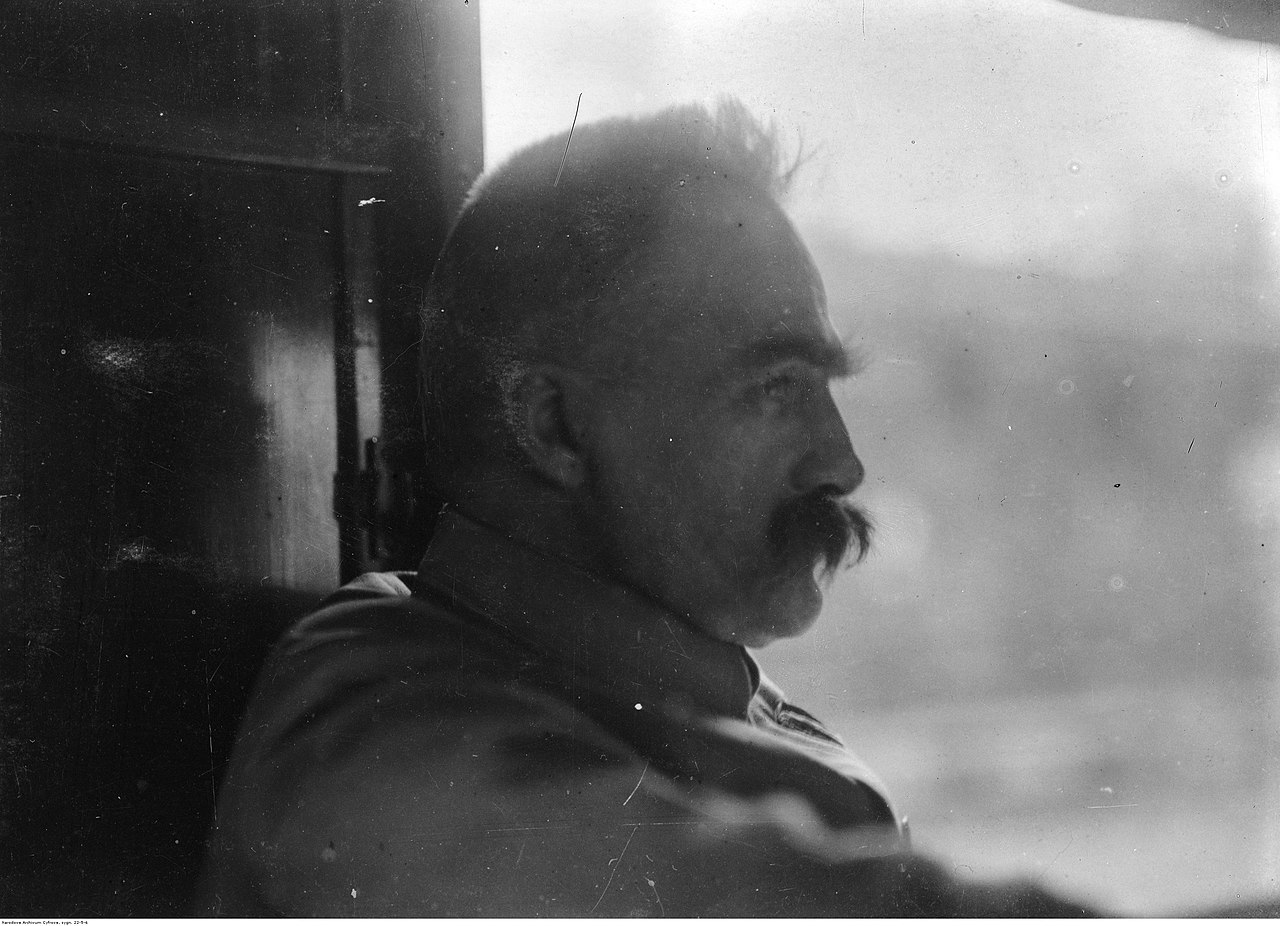

I am beginning the reflections on the significance of the Polish–Soviet War and its outcome in 1920 by quoting such new, harsh criticism of both our ‘dominant’ and ‘popular’ historiography since its author poses an important question about agency, the possibility to pursue independent Polish policies in the context of the geopolitical game played great powers. Tomasz Zarycki, an eminent younger-generation sociologist and social geographer, raises this issue as part of broader reflection on Poland’s peripheral location. Regardless of the fact whether we accept his opinion on regaining independence, I would like to posit the premise that it was precisely the Polish–Soviet War and the events of 1920, taking place with the causative participation of the Polish policy and its military tool, the Polish army, that had a significant impact on that geopolitical game of the great powers. The Polish ‘peripheries’ became, at least for some time, the centre in which the issues of pan-European or sometimes even global relevance were decided, not in line with the interests of the biggest powers, but against them. Let us have a look at the year 1920 not from the Polish perspective but from that of the said powers or their various representatives.

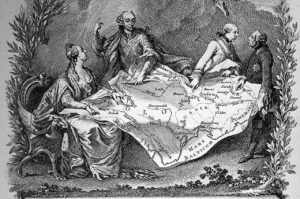

Under the Versailles system, since the very beginning, there was no place left for two big continental powers – defeated Germany and Bolshevik Russia, absent from Versailles and overcome by revolutionary fever. The remaining powers, victorious Great Britain and France (after America’s withdrawal towards isolationism) were too weak to shoulder the burden of the new order themselves. This accusation, quoted by some experts in great diplomacy, such as Henry Kissinger or George Kennan (it is worth mentioning, however, that in more recent historiography Margaret MacMillan or Zara Steiner, among others, depart from this simplified view in their syntheses), immediately indicates the most critical point, which both powers alienated from the new order strongly opposed. That critical point was an independent Poland rebuilt under the Versailles system. Poland stood between Russia and Germany. Germany could not come to terms with the loss of parts of Silesia and Greater Poland, but above all the Pomeranian ‘corridor’ in favour of Poland. Russia, which became the cradle of the world’s communist system, not only lost the territories which constituted Russia’s strategic western borderland since the times of Catherine II and Alexander I, but also lost a connection with Germany which was its impatiently expected key partner in the European revolution.

In 1919, the civil war still continued in Russia. France, in particular, hoped that White generals would be able to rebuild the strategic cooperation along the Paris–Petrograd axis, thus blocking the possibility of a German revision of the Treaty of Versailles. If the Russians had stifled the Bolshevik revolution at home, France, Great Britain, the United States, and also Italy – that is four out of the five victorious powers – would have undoubtedly decided to re-establish the partnership with Russia reborn within the 1914 borders (only without the territories of the Kingdom of Poland and the Great Duchy of Finland, already recognised by the powers as the geographic foundation of two new ‘legalised’ states: Poland and Finland). Japan, which had a great appetite for territories in the Far East, would have likely had to follow the majority on that. A new Poland, emerging on the other, western ‘pole’ of Russia, would have had to do that as well. Poland would have been then a small western annex to the Russian Republic, barely exceeding 200 thousand km2 and a population of 20 million. The United States and France agreed that there was no place – next to reborn Russia – for an independent Lithuania, Latvia or Estonia, let alone Ukraine. Great Britain, due to its maritime (Baltic) interests, looked more favourably at the idea of moderate autonomy of the Baltic republics / governorates, yet it was definitely unwilling to fight with anyone over their independence.

Still viable in 1919, that possibility of correcting and solidifying the Versailles system by including (non-Bolshevik) Russia disappeared with the final defeat of General Anton Denikin’s army. In 1920, the remnants of the White army headed by General Pyotr Wrangel were able to fight only for their survival. In the east of Europe, there was Russia – but it was Soviet Russia.

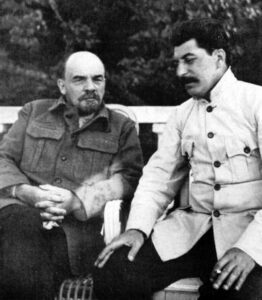

What were Russia’s strategic plans? In the hands of the Bolsheviks, it became a tool in the fight for implementing the postulates of the ideology of modified Marxism. Its goal was to expand the reach of the communist revolution and eventually – ensure its global success. The vastness of the Russian state, the estate of which fell into the hands of the Bolsheviks, as well as its scope of geopolitical perspectives and possibilities gave a wide margin of freedom to the practical policy of Lenin and his party; that margin of freedom was limited only by the requirements of the communist ideology. After all, its universal outreach, just like the physical size of its original tool, Russia, allowed for leading a policy focused on the final victory in the very long run. The most important thing was holding on to power. Since the ideology’s base was in Russia, Russia’s geopolitical interests became the interests of the communist cause.

The attitude towards Poland, towards its independence, to the aspirations outlined by Piłsudski, practically became a function of Russia’s strategic interests for Lenin. If we assume that the starting point for our analysis is November 1918, reborn Poland was at that time mostly a dividing wall, separating Russia ruled by Lenin from Germany with its revolutionary turmoil – Germany being potentially the main force of the communist ideology in Europe, with the largest workers’ movement on the continent, including quite a radical wing, with a huge industrial potential that could be decisive for the survival of the revolutionary camp in its confrontation with the powers of the Entente, victorious in the First World War: Great Britain, France, the United States and Japan. It was these powers, obviously not Poland, which were perceived by the Bolsheviks as the main enemy.

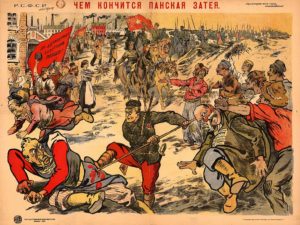

In December 1918, when the territory of the Baltic–Black Sea Intermarum was gradually left by the German army defeated in the west, scattered and weak troops of the White Russia’s soldiers did not seem to pose a serious threat for the centre of the Bolshevik power, the first attempt at the sovietisation of Eastern Europe began. The goals of the offensive were very clearly explained by the head of the Red Army, the chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic (Revvoyensoviet) Leon Trotsky. In his speech of 17 November 1918, in the place of army concentration in Voronezh, he said openly:

‘Now the fight lost any shade of the fight between us and the Germans, because free Latvia, free Poland and Lithuania, and free Finland, just like free Ukraine on the other side, will no longer be a wedge but a link connecting Soviet Russia with a future Soviet Germany and Austro-Hungary. It is the beginning of a federation, the beginning of the European communist federation – the Union of the Proletariat Republics of Europe.’

The national governments formed in the countries mentioned in Trotsky’s speech, from the Bolshevik perspective, were obviously not free. Freedom was to be brought by the Red Army. The attitude towards these ‘bourgeois-nationalistic’ authorities, which was actually the attitude towards the independence of the states emerging on the ruins of the Russian Empire, was expressed by ever-precise Joseph Stalin in his article published on 17 November 1918 in an official paper of his commissariat. The article was characteristically titled ‘The Partition’ (Sriedostienije). This partition was created by ‘dwarf national governments which due to the twists of fate found themselves between two huge centres of revolution of the East and West [and] are dreaming of extinguishing the universal revolutionary fire in Europe, of preservation of their comical existence, of turning back the wheel of history!’ ‘The counterrevolutionary partition between the revolutionary West and socialist Russia will be removed. […] There is no doubt that the revolution and Soviet rule in these provinces are just a matter of a near future,’ Stalin dotted the i’s and crossed the t’s. The attempts to implement the strategy were undertaken in January 1919 when the Red Army captured Vilnius and moved further towards Warsaw, where it was supposed to install an already formed government of the Soviet Republic of Poland. However, it was stopped by the Polish Army put together by Piłsudski. The further Soviet offensive to the West was complicated by the events of the Russian civil war in which the Reds had to primarily face Alexander Kolchak, Anton Denikin and Nikolaj Yudenich and concentrate the majority of their forces against them.

Constituted in Moscow in March 1919, the Third International was a conspicuous symbol of the topicality of the most ambitious, maximalist goals of the Bolshevik policy: igniting a revolution, at least on a pan-European scale, and breaking down the whole ‘capitalist system’. Between the minimum version – staying at the helm in Moscow and ensuring a period of peredishka (a breathing space) in the relations with the powers of the Entente, and the maximum version – revolutionising the entire Europe or the world, the intermediate path of the Soviet strategy in the international policy was formulated. This path pertained especially to Poland, as it was very strongly rooted in traditional, offensive visions of geopolitical possibilities of imperial Russia. The main partner in these visions was Germany and the target of their joint actions – Poland, or in broader terms – the entire Central and Eastern Europe. Germany did not necessarily mean a communist Germany. The final terms of the Treaty of Versailles, signed on 28 June 1919, put any Germany in the role of an uncompromising enemy of the new international order dictated in Europe by the victorious Western powers. Lenin was aware that Russia on its own, even in the pre-revolutionary imperial borders, would not withstand competition with a united bloc of capitalist powers in the long run. If consecutive attempts of exporting the revolution failed, the only chance of communist Russia’s survival and then strategic success could only be ensured by taking advantage of the divisions between ‘imperialist bandits’. Germany, hurt in its pride yet indestructible in its potential, would become under such circumstances an ideal partner to jointly crush the ‘chains’ of the Versailles system. As early as mid-April 1919, an analytical report of Polish intelligence drew Piłsudski’s attention to the fact that Bolshevik Russia might choose such Realpolitik based on the concept of building a camp of forces opposing the British-French-American hegemony. The report outlined a vision of a kind of anti-Entente, grouped around Red Moscow, founded on an axis with Berlin and expanding through Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Austria towards Italy; that would have clearly meant a death sentence for Poland, a return to geopolitical cooperation of the powers that had based their alliance on the partitions of Poland lasting for more than a century.

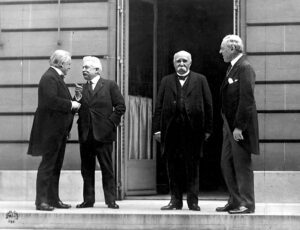

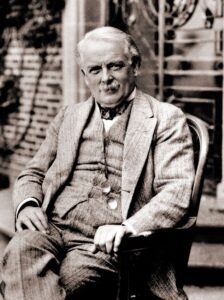

On the eve of the winter of 1919/1920, when the White Russia actually lost the civil war against the Bolsheviks, the revolutionary mood in Central Europe, Hungary and Germany were dampened again. In that favourable moment, the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George returned to the notion of calming the situation in the East through the actual recognition of Bolshevik rule, using the slogan of ‘peace through trade’. As their hopes for the restauration of White Russia failed, the French preferred to support the concept – primarily directed against the Germans, and only secondarily against Bolshevism – in which the security of Europe in the East was based on a system of states succeeding the former Russian and Habsburg empires. Poland was supposed to be the main link in this ‘cordon sanitaire’. Under such circumstances, Lenin could take two strategic options into account. According to the first one, there would be a temporary agreement with the British ‘bandits’; sooner or later, the weaker French ones would have to come to terms with that pact and also recognise the Bolsheviks’ rule at least in Russia and Ukraine. Obviously, the tactical agreement in Europe did not preclude severe fighting with ‘imperialists’ in the countries of Asia or even Africa (the agenda of such fights was reintroduced by Trotsky in August 1919). Also, there still remained a possibility of winning the pivotal conflict in Europe between the western powers and the Germans who had not accepted the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

All Bolshevik leaders without exception perceived Poland and Piłsudski solely as the most dangerous tool for the new plans of the main ‘imperialists’, even if they did not even act jointly anymore (Lenin noticed a discord between London and Paris, even though he suspected that it might be just a tactical game to throw him off the scent); still they could act as a French gendarme of the Versailles system. In parallel to the propaganda offensive, in which Bolshevik Russia was presented as an advocate of peace and Poland as an instrument of warmongers, the Soviets started preparations for the implementation of the second strategic line. It was supposed to lead to a military crushing of Poland and her sovietisation. In such a way – after breaking the chain around the Soviet state – a direct border with Germany was to be won. And what next? Lenin was very pragmatic about the future. After the liquidation of ‘lordly Poland’ (panskaja Polsza), it was possible to stop there in order to make a temporary compromise with western ‘imperialists’ at new, even more beneficial borderlands, or – under favourable conditions – go further and take the red banner to Berlin, Paris, London…

Well aware of the impending danger, Piłsudski decided to take over the strategic initiative and without waiting for the attack of the Red Army which had been planned and prepared since January 1920 at the Belarusian section, he made an attempt at implementing his own geopolitical vision: in alliance with Symon Petliura’s Ukrainian government, he marched towards Kiev. It was where independent Ukraine was to be established and maintained, thus blocking the possibility of the Soviet expansion, or in a geopolitical sense, blocking the westward expansion of the Russian Empire. Piłsudski saw a chance of strengthening the Versailles system by adding the ‘Eastern chapter’ to it. Any Russia, including Soviet Russia, but also Germany, were to come to terms with the independence of Poland and of many other new states that emerged between the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea, and consequently with the Versailles system – thanks to building a larger political commonwealth in the East of Europe, one based on the Warsaw–Kiev axis. Instead of a thin Polish ‘partition’, as Stalin called it in his article, a new geopolitical structure was to be established: with Poland, Ukraine, possibly also with Lithuania (and Belarus) associated with Poland, as well as with new Baltic States and Romania. It was supposed to fill the space between Russia and Germany solidly enough as to make the return to the previous state discouragingly difficult for both neighbours. Piłsudski believed that the facts accomplished in the victorious campaign would be sufficient to convince both Russia and Germany that the new geopolitical order in the east of the continent can be reconciled with their crucial economic interests and stability of the entire international system.

He did not receive support of western powers for his plans. To the contrary, as I wrote extensively elsewhere, especially the British policy shaped by Prime Minister David Lloyd George, was directed at a geopolitical compromise with Russia, even Soviet Russia, at the expense of Poland. It was the first lesson of appeasement, that is in this case of satisfying the imperialist ambitions of Lenin’s Moscow towards Eastern Europe, at least up to the German border. Hopelessly dreaming of the return of non-Bolshevik Russia as its natural ally in the East, France gave up its own active policy towards the Polish–Soviet conflict of 1920 after the defeat of the Whites, just passively protesting against Lloyd George’s policy.

During the civil war still waged in Russia in 1919, Great Britain provided the Whites with a lot of military supplies yet did not want to be seriously involved in military support for them. Since early 1919, the liberal Prime Minister Lloyd George had been looking for opportunities to reach an agreement with the Bolsheviks to involve Russia – as it was – in some forms of cooperation, starting with trade. Secretary of State in the War Office Winston Churchill, opposed to that tendency, as well as Lord George Nathaniel Curzon, a new Secretary of State at the Foreign Office, could no longer slow it down after the Bolsheviks tipped the scales in their favour in the civil war in early 1920 and they became the actual Russian hosts. In January 1920, the Prime Minister, thanks to his argument about the need to re-launch the trade exchange with Russia, managed to convince first his colleagues in his coalition cabinet and then also the French, resistant to the idea of any talks with the Bolsheviks, to commence such talks anyway. Against the facts but on the basis of an ‘expert opinion’ in line with his point of view, the British Prime Minister argued that Soviet Russia had huge grain stocks at its disposal, which could satisfy the needs of Europe at the verge of a famine.

Finally, the concept of talks with the ‘Russian trade delegation’ imposed by Lloyd George was undertaken at the conference of the Entente leaders in San Remo on 25 April, which brought together representatives of Great Britain, France (with Alexandre Millerand, the new Prime Minister – starting from 20 January – who was also the Minister of Foreign Affairs in his own cabinet) and Italy (with the Prime Minister Francesco Nitti); formally, together with ambassador Keishirō Matsui representing Japan, they constituted the Supreme Council of the Peace Conference.

In spring 1920, when Piłsudski started his great strategic action aimed at Kiev and Lenin prepared a military offensive to destroy Poland, the British Prime Minister, at the conference of the allies in San Remo, forced through his policy of economic and then political talks with the delegation of Soviet Russia. Poland did not receive any help from the western powers. When after seven weeks in Kiev the Polish Army had to withdraw from the Dnieper in June 1920 as the Red Army was attacking in the north, and Symon Petliura’s rule did not muster enough support among the Ukrainians in such a short period after its introduction, the questions about the future of the Versailles system in the east of Europe returned with a new force. Having been prepared for months, the attack mounted by the Red Army on Warsaw was launched with, as it seemed, unstoppable force. Its goal was to destroy not only Poland, but the whole Versailles system. In July 1920, Lenin, who was in charge of that strategy, wrote to Stalin, who played the role of a political commissar of the front attacking Galicia:

‘Zinovev, Bucharin and I as well believe that the revolution in Italy should be ignited now. I personally think that in order to achieve that, Hungary and maybe Chechia and Romania should be sovietised.’

Stalin, who promised to capture Lwów within a week, responded the following day:

‘Now that we have the Comintern, defeated Poland and the more or less decent Red Army […] it would be a sin not to ignite a revolution in Italy. […] We should consider the question of staging an uprising in Italy and such fragile states as Hungary, Chechia (Romania will have to be broken down). […] In a nutshell: we need to raise an anchor and set off on a journey, before imperialism manages to somehow repair its declining cart.’

Lenin, excited by these prospects, even as late as 12 August exhorted impatiently: ‘From the political standpoint, it is of paramount importance to kill off Poland.’

Yet Poland was not to be killed off. I am not going to discuss here the course of the Battle of Warsaw, victorious for Poland, or its equally victorious continuation at the Battle of the Niemen River. We are talking only about the consequences. Let us first recall then how deep Lenin’s disappointment was. Clashing with the force of mature patriotism, well-established in the majority of society, was a new experience for the Bolsheviks. The attempt at sovietising Poland was halted at what Richard Pipes has called European nationalism, which was a positive distinguishing feature for Poland, so much different from social anomy on which Bolsheviks built their success in Russia, Ukraine or Belarus. ‘Damned, dark Poland’ – as Kliment Voroshilov, Stalin’s comrade from fights near Lwów wrote on 4 September – showed ‘chauvinism and blunt hatred towards the “Russkis”’. For the following twenty years, there was no talk anymore of Soviet Hungary, Czechoslovakia or Romania, and the peace treaties between the Bolsheviks with ‘bourgeois’ governments of the small Baltic republics remained in force. Lenin radically verified his whole strategy: ‘moral’ and material help for the cause of revolution in imperialistic states was to be continued, or even intensified, especially in the colonies, but direct military involvement of the Soviet state in the export of revolution was out of the question for many years, at least in Europe. The Versailles system was saved for eighteen years by the Battle of Warsaw and then the Battle of the Niemen River. At the same time, a chance for independent development of Central and Eastern Europe was saved, too. At least of its part and at least for some time.

Nikolai Trubetzkoy, the creator of a new geopolitical concept called Eurasianism, still influential nowadays, assessed the Polish victory at the Battle of Warsaw and cutting Soviet Russia off from Germany due to the Treaty of Riga from a totally different perspective. After the defeat of the last outpost of White Russia in Crimea, the idea of Eurasianism solidified among young Russian emigrants in Sofia. For its advocates, led by Trubetzkoy and Peter Savitsky, the most important thing was to juxtapose Russia and Europe, that is the ‘Romano-Germanic world’. Russia was to find strength to withstand the everlasting confrontation with the West in its separate identity, which was not European but Eurasian. The summer of 1920 was the moment when the discussion of the political significance of such identity became particularly invigorated: first when the Bolsheviks acted as defenders of ‘Ruthenian territories’ against the attack of ‘Polish lords’ on Kiev, and then when they mounted a great westward offensive, which was to take a new Red Russia ‘through the corpse of White Poland’ towards the centre of Europe. Trubetzkoy made some extremely interesting remarks about the Bolshevik movement and the West in a letter to his friend in Prague, Roman Jakobson, who was a supporter of Eurasianism and the creator of structuralism in linguistics. Trubetzkoy wrote that letter already in the context of the end of the Polish–Soviet War and the closing negotiations in Riga. Consequently, he suggested a holistic overview of the war and reflections (from the perspective of a Eurasianist) on the blood-curdling consequences of a hypothetical success of the Bolshevik attack on Warsaw and the Red Army reaching Berlin. If Lenin had succeeded in implementing his plan and bolshevised Germany – ‘the axis of the world would have immediately shifted from Moscow to Berlin’. Trubetzkoy was fully aware that the ideological foundation of Bolshevism – communism – was by no means Russian, but fruit of the ‘Romano-German civilisation’.

The German would have built the ideal of the communist state in line with those western sources, the ideal impossible to implement in Russia, due to its cultural difference. After the collapse of Poland and Tukhachevsky’s reaching the centre of Germany, it would have been Berlin that would have become the ‘capital city of a pan-European or maybe even pan-global Soviet republic’. Trubetzkoy had no doubts:

‘There were always masters and slaves, there are and there always will be. They also exist in the Soviet system, in our Russia. In the global republic, the Germans, or generally speaking – Romano-Germans, will be masters, and we, that is all the others, will be slaves. The level of slavery will be directly proportional to the “cultural level”, that is the distance from the Romano-German standard.’

With his decisively anti-communist attitude, Trubetzkoy did not perceive Bolsheviks as the ‘saviours’ of Russia. It was rather a result of their defeat in the Battle of Warsaw and stopping their march to the West that allowed them to play the role of a formation that maintains separateness or even opposition between Russia and the ‘Romano-German’ world. The assessment of the geopolitical consequences of the year 1920 by Eurasianists can be summarised in one sentence: Poles did not only save Europe from sovietisation but also saved (Bolshevik) Russia from being subjugated to the Western yoke again.

For their part, Lenin and Stalin had to account for their premature hopes of dismantling Poland and the Versailles system at the ninth conference of their party, in late September 1920. They both stated that as Bolshevik revolutionaries they could not help but try and shake the foundations of the entire European capitalist system. During his secret speech at the conference, revealed only several years ago by Russian archivists, Lenin used an interesting phrase about ‘feeling with a bayonet’ (szczupanije sztykom) to check the maturity of Poland and the entire Central and Eastern Europe for sovietisation, emphasising once again that it was not about Poland itself, nor even about her neighbours, but about challenging the whole Versailles system. He dotted the i’s and crossed the t’s reacting to a critical opinion voiced by Karl Radek, who sarcastically remarked that there was no need to ‘feel’ with a bayonet and it was enough to read newspapers to realise that the revolution in the West, especially in England, was not yet sufficiently mature. Lenin remarked then that he was not focusing on London but mostly on Berlin… The ‘leader of the revolution’ returned to the notion of a temporary agreement with the ‘imperialist encirclement’. He had to conclude it on much worse terms than the ones from Lord Curzon’s proposal of July 1920. Symbolically, it coincided – in March 1921 – with the signing the Treaty of Riga with Poland and a trade agreement with Great Britain.

Piłsudski took advantage of a certain loop in the deployment of forces that appeared in the east of Europe after the First World War, during the civil war in Russia. He did not want to waste that short period when maximum effort on the part of Poland could tip the balance in her favour due to a temporarily paralysed potency of the country’s great neighbours. It was not only the Entente, however, but also the population of the Eastern European Intermarum that remembered rather the experience of the power of Russia (and Germany) that could be balanced by western powers – if they so wanted – but not Poland left to its own devices, whose point of departure in 1918 was the same as that of the other nations in the region depraved of their own statehood. The attempt to fundamentally change the geopolitical architecture of Eastern Europe was not successful. Poland defended its independence but remained alone with its projects. Even if Poland was not very small, not reduced solely to the role of a buffer of Germany or Russia, she was still too small to hold her ground between hostile Germany and Russia driven by totalitarian ideologies. The basic goal of the geopolitical ‘revolution’ planned by Piłsudski is probably best expressed by a vision of ‘The Eastern Empire – the Polish Empire of Dominions’ as it was defined by Michał Römer, a would-be collaborator on the project (in the Lithuanian section). The empire, combining the territories of Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania and Belarus – in the form of a federation, a close alliance or any other close strategic relation – was supposed to finally become an alternative for Russian domination (or German-Russian domination) over Central and Eastern Europe. But that did not happen.

The Peace of Riga was tantamount to the end of military conflicts wrecking Eastern Europe since August 1914 and the beginning of stabilisation for many millions of inhabitants of the region. In that sense, it definitely closed a certain international legal framework of the new order which had been introduced in a large part of Europe by the Treaty of Versailles. The states that gained independence in March 1921 kept it for another 17 – 18 years. Is it long or not long at all? Researchers who study this issue from the perspective of 1939 – the Ribbentrop–Molotov Pact and its catastrophic consequences – often notice an essential premise for the future disaster in the terms of the Peace of Riga. The geopolitical agreement between Russia (ideologically the USSR) and national-socialist Germany is explained by both powers’ obvious lack of acceptance of the territorial concessions in favour of Poland, which were imposed on Germany at Versailles and accepted in Riga by Soviet Russia, but most of all, by lack of consent from Moscow and Berlin to be separated by the Polish ‘partition’. That danger – of an agreement between Moscow and Berlin, lethal for the Versailles order and concluded owing to Poland’s fault and excessive ambitions – was also noticed by the contemporaneous, regardless of their political allegiance.

In this context it is worthwhile to refer to comments by Viktor Kopp, a Soviet diplomat who tried to orchestrate a geopolitical agreement between Moscow and Berlin in 1920. That autumn, Kopp complained that such an agreement had not been concluded. He recalled that it was a great opportunity rendered impossible by the Peace of Riga. Not a very well-known figure at that time, Hitler could not be a party to such an agreement back then, but the German ‘national-Bolsheviks’ – as Kopp described them – and militarists associated with General Erich Ludendorff were already a real power in politics, at least in German public opinion. They did not win in 1920, contrary to Kopp’s hopes and efforts. Strengthening independent, relatively strong Poland, stabilisation of the Versailles order in the east of Europe by the Treaty of Riga and lack of a direct territorial link between Russia and Germany – all these factors truly weakened the pro-Russian, Eastern orientation in German politics. The concept that Kopp wanted to implement meant an alliance between Berlin and Moscow, not only against Poland but also Western Europe, against the victorious Entente. In German politics after 1920, that orientation had its obvious continuation – starting from Rapallo in 1922, through consecutive Soviet–German political and trade agreements. However, it was not the dominant orientation in the following years: to the contrary – until as late as 1933, the prevailing tendency was not to provoke the victorious western powers, to gradually fit Germany into the new order of Versailles Europe.

Referring to an alternative history scenario: a potential success of the Eastern orientation in German politics and rapprochement of the Bolsheviks in Russia with ‘national-Bolsheviks’ in Germany as early as in 1920, we wish to consider two more issues. Since that plan was actually prepared already in 1920, and its main executor assessed the consequences of the Treaty of Riga the way he did, perhaps the Treaty could be perceived as a political agreement which actually postponed, delayed for many years, a geopolitical alliance between communist Moscow and revanchist Berlin, so disastrous in its consequences (not only for the Versailles order, but for millions of human lives)? If the pact between Stalin and Hitler was concluded in August 1939, was it really a consequence of the imperfections of the Peace of Riga, signed 18 years previously, or rather a result of political mistakes made not only in Riga and Warsaw, but also in other European capitals, and not in 1920 but in the second half of the 1930s?

One could also consider an alternative for the Polish Army’s victory at Warsaw and the terms of the geopolitical compromise obtained after that victory in the Treaty of Riga proposed by David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister. Its essence was to include Soviet Russia as fast as possible in European political and trade exchange arrangements, with the great powers parties to them. I have already discussed elsewhere the origin of that concept and attempts at its implementation since January 1920. Let me just recall here that for the British Prime Minister Poland was just an obstacle, unless it was possible to shrink the country to the size acceptable to both Moscow and Berlin, the crucial partners of the new exchange. Hence the idea of the Curzon line, actually delineated by Sir Philip Kerr, Lloyd George’s personal secretary and the closest political confidant, and presented in a note by the Secretary of State at the Foreign Office to Georgy Chicherin on 11 July 1920. As a consequence of the concept, talks with a Soviet trade delegation were conducted in London starting from late May, then transformed into political negotiations thanks to Lloyd George’s initiative. Their significance was confirmed by the participation of Lev Kamenev (the person number three in the hierarchy of the Soviet state and the Bolshevik party). As early as 4 August, he paid a visit at 10, Downing Street, and six days later he listened from a VIP lodge in the British Parliament to the Prime Minister Lloyd George, who justified the need for Poland to accept the Soviet terms of peace (as a matter of fact consenting to capitulation and sovietisation).

From the start, Lloyd George assumed that Poland would lose in the military clash with Soviet Russia. In mid-August, he left for Lucerne in Switzerland, with the deep conviction, which was also corroborated by Maurice Hankey, a secretary of the Cabinet coming back from his information mission to Poland, that Warsaw’s surrender was inevitable. He hoped that the negotiations conducted in London for three months with representatives of Red Moscow would bring some results at that critical time. He wanted to take advantage of the moment to negotiate a new pan-European political order, which would actually be a significant correction of the Versailles system. An element of that strategy was an earlier idea to hold a conference in London where the main role – apart from the host – would also be played by a high representative of Soviet Russia. Smaller countries of Eastern Europe, Russia’s neighbours, would just be able to listen to the verdict issued by the powers.

Lloyd George’s political project failed due to the decisive Polish victory in August, won against London’s official suggestions that Warsaw should surrender to Moscow. Richard K. Debo, a Canadian historian of Soviet diplomacy, has showed in an interesting way the possible consequences of the success of Lloyd George’s plan. In the light of the available source documents, he had no doubt that the Soviet victory over Poland would mean at least Poland’s sovietisation. Lenin and his comrades from the Politburo would then be able to conclude agreements with Germany (in the spirit of the ones Kopp was drafting that summer) and Great Britain. The British Prime Minister assumed that a wave of sovietisation would stop at the German border. After 20 August, he met in Lucerne with the Italian Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti, who was known as an advocate of Lloyd George’s line in his policy towards Soviet Russia. At the same time, the German Foreign Minister Walter Simons was also in Switzerland, not far away. Lloyd George and Giolitti could have jointly made an appeal to Simons and the French leader Alexandre Millerand to meet promptly at an international conference where they would have been able to decide about the necessary revision of the Treaty of Versailles in order to avert the crisis; obviously together with representatives of Soviet Russia, considered a power equal to them. Debo asks a rhetorical question: whether France, naturally reluctant to accept such a solution would have been opposed if it had had to confront Great Britain on that and it would not have had even a ‘replacement’ ally in the east of Europe (after Poland’s fall)? Would Paris have dared to push Germany towards the wide open arms of Red Moscow? There would have been a conference held, yet fully ‘successful’, and it would have had similar consequences to those of the 1922 events in Genoa and Rapallo.

Yet could the conference that Lloyd George had in mind have brought lasting results and stability although it could have actually freed Europe from the spectre of another great war? The Canadian historian have expressed serious doubts about that. He claims that the very strength of Polish nationalism, pushed then to the margin, would have been a real Achilles’ heel of both the system of Soviet domination and the entire international order in Eastern Europe. Soviet Russia was not powerful enough yet, according to Debo, to broaden its sphere of influence all the way to the German border.

‘The inescapable truth was that Moscow was badly overextended. Nineteen twenty was not 1945 (or even 1939) […]. Piłsudski did the Bolsheviks a favour in driving them out of Poland in 1920. In the long run Soviet Russia probably benefited from a territorial settlement which so accurately reflected the realities of power at that time. The existence of a Soviet Poland that could neither be sustained from within nor defended from external aggression would have been an enormous source of weakness, seriously endangering the internal stability and international security of Soviet Russia.’

The alternative scenario presented by the Canadian scholar includes two assumptions, which were close to Lloyd George himself: one formulated explicitly, that Poland would lose (so she would not have a say in the new political arrangement of 1920), and the other – accepted in secret – that Soviet Russia would play a role in that scenario assigned by the ‘Welsh wizard’. Yet it should be remembered that Lenin and his comrades from the Politburo did not have such intentions at all. They wanted to take advantage of Lloyd George and his game; they did not plan to stop at the German border. What pointed to such intentions was not only correspondence between Lenin and Stalin quoted above, from late July, but also specific actions from mid-August (e.g. preparing printing presses with German fonts and ‘German comrades’ who were to launch a new wave of propaganda behind Poland’s western border after the fall of Warsaw). Seen from that perspective, Lloyd George’s concepts proved entirely unrealistic.

At the beginning of September, the British Prime Minister realised that he could not control the events in Eastern Europe anymore. Perhaps that is the most important meaning of the Treaty of Riga. Even though we often consider it (and rightly so) to be a certain supplement to the Treaty of Versailles, it must be remembered that it was not dictated by the victors in the First World War. It was not an order imposed by western powers, but rather an expression of their powerlessness. When in 1920 the United States actually turned their back on European problems, and many discrepancies appeared in the relations between London and Paris in terms of the attitude towards defeated Germany as well as Russian (Soviet Russian) and Eastern European affairs in general, the notion of ‘allied and associated powers’, which was to guarantee strength to the new post-war order, became void. Great Britain had more problems with retaining its huge empire than possibilities to take advantage of its power in Europe. Lloyd George saw that France as an associate was not sufficient, even with additional support from Italy. That is why he looked for candidates elsewhere – among the states that had always been powers: Germany, even defeated, and Russia, even Soviet Russia. Great Britain competed with Russia elsewhere – in Asia. It was afraid of that competition in Turkey, Transcaucasia, Afghanistan and India (the head of the Foreign Office George Curzon focused his whole attention on the Asian fronts of potential competition with Soviet Russia and he was totally passive in matters related to Poland and the entire region). In Eastern Europe, Great Britain would have been willing to share the responsibility for the order with Russia, also to draw it away from Asian affairs. Lloyd George’s intention was to make the order of Versailles resemble more the order of Vienna, with only the powers making decisions and sharing responsibility. Not for the first time, smaller states, nations and their aspirations had been perceived as a certain problem that the powerful ones had to handle.

The Polish victory at Warsaw and then the peace treaty negotiated independently by Poland with Soviet Russia aroused Lloyd George’s irritation and then resentment. It might be the reason for some bitter remarks directed at the Versailles system especially by Anglo-Saxon historians, and even more so at the Versailles–Riga system, which Lloyd George failed to ‘reform’ in the spirit of the former concert of powers. In this perspective, we can see a special significance of the Polish military victory in August 1920 and then of the Treaty of Riga. The Treaty did not fulfil all national aspirations present in Eastern Europe after the First World War. Some of them – especially Ukrainian and Belarusian – were painfully trampled down. It was its clear weakness (it was not the fault of ‘sinister conspiracies’ of the National Democracy and its delegate in Riga Stanisław Grabski as a legend concocted in Piłsudski’s camp would have it, the legend repeated even nowadays by such renowned researchers as Timothy Snyder; it was finally rebutted by Jerzy Borzęcki in his masterful monograph on the course of the Riga negotiations). Still, the treaty broke one rule – that only great powers, without any say from smaller states – could decide about the shape of the international order, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, where the role of sole responsible hosts was assigned in that imperial mentality to Germany and Russia. Poland paved the way for smaller states which wanted to decide independently about their fate, with acceptance from the powers. Soviet Russia felt pressured, at least temporarily, to recognise that right and Western powers, at least in that case, as well. In the history of this part of Europe, which from the western perspective is most often perceived as an area between Russia and Germany, the Treaty of Riga remains an example of respecting sovereignty of smaller states by the powers.

This part of Europe turned out rather ephemeral since it lacked political support from the western powers, especially those Anglo-Saxon, that Piłsudski called for to no avail. Poland alone, without support of the West, could not achieve a sustainable geopolitical breakthrough. Yet it proved that, practically speaking, such a breakthrough was possible. And it saved the Versailles system for almost two decades. The independence of smaller nations and states located at the intersection of the German and Russian Empires would come back in a renewed form in 1991. Then it would be expanded to include countries that did not gain independence in 1920, such as Ukraine or Belarus. Would it have been possible if it had not been for the memory of the 18 years – ‘donated’ to Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, Romania, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia (even though the last mentioned does not want to remember that but still undoubtedly constitutes a part of the region and its commonwealth of geopolitical fate)? These were the years, let me reiterate, ‘donated’ against the wishes of the British Prime Minister, against the openly declared passivity of the United States towards this area and that particular problem as well as against the attempt made by Lenin, Trotzky and Stalin to pierce and tear down, immediately in 1920, the sriedostienije, the thin partition between the powerful Soviet fist and the strong hand of the German worker.

I will leave the reader with this question and reflection over an issue of the agency and autonomous significance of the Polish policies (and army) – at least those of 1920.

Author: Andrzej Nowak – Polish historian and public intellectual, professor of Jagiellonian University and in the Institute of History (Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw). He was visiting professor and lecturer at many universities (Columbia, Rice, Harvard and the University of Virginia, as well as Cambridge, University of Toronto, Simon Fraser University and others). Author of more than twenty books as well as co-author and editor of several others, mostly on Eastern European political and intellectual history. Several of them are available in English.

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin

REFERENCES:

Jerzy Borzęcki, Pokój ryski 1921 roku i kształtowanie się międzywojennej Europy Wschodniej, Warsaw 2012.

Richard K. Debo, Survival and Consolidation. The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918–1921, Montreal 1992.

V[ladimir] I[ilyich] Lenin, Nieizwiestnyje dokumienty 1891–1922, J.N. Amyantov, J.A. Achapkin (eds.), W.T. Łoginow, Moscow 1999.

Andrzej Nowak, Pierwsza zdrada Zachodu. 1920: zapomniany appeasement, Cracow 2015.

Andrzej Nowak, Polska i trzy Rosje. Studium polityki wschodniej Józefa Piłsudskiego (do kwietnia 1920 r.), Cracow 2001.

Richard Pipes, Rosja bolszewików [orig. Russia under the Bolshevik Regime], translated by Władysław Jeżewski, Warsaw 2005.

Polsko-sowietskaja wojna 1919–1920 (Ranieje nie opublikowannyje dokumienty i matieriały), Part I, I[wan] I. Kostyushko (ed.), Moscow 1994.

Timothy Snyder, Tajna wojna. Henryk Józewski i polsko-sowiecka rozgrywka o Ukrainę [orig. Sketches from a Secret War. A Polish Artist’s Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine], translated by Bartłomiej Pietrzyk, Cracow 2008.

Zara Steiner, The Lights that Failed. European International History 1919–1933, Oxford 2005.

Wiktor Sukiennicki, Przyczyny i początek wojny polsko-sowieckiej 1919–1920, Part II, ‘Bellona’ 1963, vol. 3–4.