The history of Warsaw still raises many questions, especially if we look at it through the prism of today’s experiences. Błażej Brzostek, author of the book “Wstecz. Historia Warszawy do początku” (“Backwards. A history of Warsaw to the beginning”) talks about the changing directions of the city’s development, giving historical understanding of the capital city and problems with the sense of community among its inhabitants.

Natalia Pochroń, Polish History Museum: Your book about the history of Warsaw starts from 2021. Where did you get the idea to reverse the traditional order of storytelling and look backwards?

Błażej Brzostek: By inverting the narrative, I wanted to avoid linear guidance of the reader from the oldest times until today because it creates a tendency to build great cause-and-effect sequences that justify everything, presenting all events, customs and structures as an effect of the historical process. I tried to look a bit further, and go beyond the usual patterns.

And beyond the well-known facts? In your book, you focus on lesser known people and events in the history of Warsaw.

Yes, otherwise there would be another, slightly more detailed history of the city. I wanted to avoid it and create something new, I tried to mix different points of view, and combine different perspectives. Thus, this narrative is unpredictive, characters who are completely unimportant from the point of view of textbooks appear next to well-known heroes. For me, however, they are extremely important – their experience shows a certain aspect of the reality of Warsaw that we would probably not have taken into account otherwise.

You wrote that a city historian did not have to, and even should not focus on, written sources in their research. So what sources did you reach for when writing his book?

I tried to reach for various sources, and listen to many voices. The first and most important was the experience of urbanity itself – the elusive atmosphere of the city, bits of conversation and impressions. It is an experience that is difficult to define, recorded in stories, heard in conversations, and often unregistered. Most of it is lost. However, if we manage to notice and use it, it creates an image of the everyday city. There is a paradigm according to which one should approach the research object with the greatest possible distance, without emotions. I believe that you shouldn’t avoid writing about close matters. Telling about the city you live in forces you to revise your habits and avoid easy answers. I am not a fan of Warsaw, I do not like to call myself a Varsavianist, but I am interested in this city, which is already a sufficient basis to write something about it.

Warsaw is quite a young city if we look at other European capitals. When did it become the capital city in the awareness of Poles? To what extent did they understand the idea of a capital city at all?

It depends on how we define the Poles of that time. In the medieval mentality, neither the townspeople – the backbone of Warsaw at that time – nor the peasants were considered to be [Poles]. It was the nobility who were primarily considered Polish. For them, as a political nation, granting Warsaw the status of the capital city at the end of the 16th and at the beginning of the 17th centuries was a very important fact and increased its rank. At that time, it became the most important city of politics, commerce and service in the Republic of Poland. There was a royal court in this city, and the nobility flocked to it and built their seats there – from magnificent palaces to modest wooden manors. It was their Warsaw, and it was a completely different city from the Warsaw of merchants and craftsmen.

A few centuries later, the situation changed – the 19th-century elite was not satisfied with life in Warsaw, while for peasants or workers it was a megalopolis, a promise of all the best.

That’s true but a lot happened during that time. The Republic of Poland fell, Warsaw ceased to be the capital of a great state, and became the capital of small state forms – the Duchy of Warsaw, and later the Kingdom of Poland. Both of these states were non-sovereign, and subordinated to the neighboring powers, but at the same time were quite modern, equipped with a centralized and developed administration, as well as police and tax systems. At the beginning of the 19th century, Napoleon gave the peasants personal freedom, and therefore they began to migrate freely – first from one farm to another, and then also to the cities. Gradually, they also began to settle in Warsaw. Numerous metal and cloth factories and breweries were established, and the demand for workers grew.

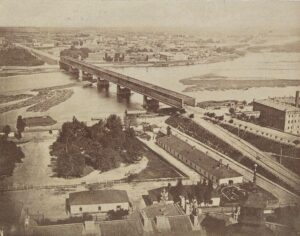

At the same time, in the second half of the 19th century, Warsaw was a city fully dependent on the Russian authorities, there was no self-government, no representation, nothing that would allow the citizens to govern themselves. This is the drama of that city – it grew dynamically as a large industrial and commercial center, very modern, and at the same time devoid of subjectivity.

The time of partitions for Warsaw was the time of two foreign governments – Prussian and Russian. How did this period affect the city’s development?

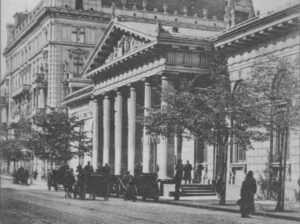

The Prussians were, first of all, people of the Enlightenment and they organized life in Warsaw in this spirit. A lot of officials came to the city to put things in order and reform it – they set the traffic rules, numbered the carriages, and organized the horse post office anew. Then came Napoleonic rule with further regulations and various urban projects aimed at destroying the medieval image of the city and giving it a modern character. Many of the regulations introduced at that time survived in Warsaw for many years, and also after regaining independence. Exactly the same happened under Russian rule. Even if the rulers were focused on St. Petersburg, they changed Warsaw to make it similar to Western models.

Did 19th-century Warsaw look like Western cities?

Yes and no. Initially, the reforms actually were carried out in this direction. From a certain point, however, and especially after the suppression of two uprisings – the November and January – the Russian authorities began to treat Warsaw as a hostile city. First of all, they greatly reduced its independence, and secondly, it began to resemble Russian models, following the principles of neo-Byzantine architecture. This is clearly visible, for example, in the Praga district of Warsaw – in the 19th century it was designed practically from scratch, following the pattern of provincial cities. The authorities did everything to show that Warsaw was far from the Western models.

And so in 1915 the process of re-polonization of the city began. What did it basically mean for Warsaw?

Initially, it was primarily a change of occupation – from Russian to German. It created much greater chances and possibilities. The Germans agreed to the opening of the university or the establishment of a municipal self-government, which the Russian authorities did not want to allow. In this way, citizens had a foretaste of national freedom, but it was still under a truly oppressive occupation. However, it soon came to an end – the Germans left Warsaw and almost overnight it became the capital of a great state. Everything happened dynamically and unpredictably – the more so as soon another threat appeared, this time from the Bolsheviks.

Repelling them from Warsaw and defending the capital in 1920 is, in my opinion, a key moment for understanding Polish independence. For while the rebirth of Poland was decided by the superpowers, Poles had won their own freedom. The public became involved in this struggle, be it through voluntary conscription to the army or through fundraising efforts to support the military effort. The inhabitants of Warsaw gained the sense of agency that they had lacked, they gained the awareness that they owed their victory to themselves. It seems to me that in this sense, 1920 can be considered the moment when Warsaw truly became the capital of Poland – not only realistically, but also symbolically.

In the interwar period, Warsaw, with a population of one million, was among the ten largest metropolises in Europe. What kind of city was it in the eyes of its inhabitants and visitors?

It depends on where the visitors came from. Interwar Warsaw was the capital of an increasingly authoritarian state, especially after 1926. It also fostered the vision of a city using coercion against the rest of the country, full of various intrigues, political alliances, and, at the same time, was “loaded” with state money. Moreover, Warsaw was definitely not a model of a civilized city. When someone came from Poznań, they immediately noticed that the streets were less paved, the architecture was more chaotic, and the contrast between wealth and poverty was much more striking. Visitors from Krakow were a bit jealous and convinced that Krakow was the spiritual capital of Poland and deserved more, and at the same time would never win against Warsaw in terms of development and investment. For newcomers from Vilnius, the capital was a city full of chaos, contrasts, dirt, devoid of Vilnius’ charm. And then there was an anti-Semitic stereotype. So it was quite a negative image – foreign Warsaw, which needed to be modernized if not destroyed and built anew.

The 1930s were the time of gigantic urban projects in Europe – Mussolini was rebuilding Rome, and impressive urban plans were developed for Berlin and Moscow. Was Warsaw developing just as dynamically?

Yes, although a few objections must be made here. The interwar period was not an easy time for Warsaw. After 1915, it was cut off from the eastern markets, which had constituted the basis of its development, in addition to the negative economic policy of Germany towards Poland and the great crisis of the early 1930s. So there was a common feeling that Warsaw had deteriorated economically. At the same time, however, the role of the capital city and the concentration of capital in the city allowed for attempts at urban changes and reforms that were to change the character of the city, as this kind of civilization was not considered an advantage but rather a disadvantage.

At the same time, “anti-Warsaw” was designed on the outskirts of the city. First by introducing garden-cities – idyllic, quite elite districts with clusters of small single-family houses. The second “anti-Warsaw” was socialist Warsaw, including workers’ estates and housing cooperative building blocks. And finally, the third “anti-Warsaw” – representative, associated with great state investments in wealth and splendor. In the 1930s, among others, construction of the great Piłsudski district or the impressive Temple of Divine Providence began. And this was Warsaw in the Mussolini style – faced with granite, monumental, meant to show the power and possibilities of a modern city.

Various kinds of splits were even more visible during the occupation. I am thinking not only of the “physical” division into districts cut off from each other, into the German, Polish and Jewish states coexisting side by side. The social and political split was equally deep – into different groups of fighters, people with different experiences of war. After the occupation ended, were these divisions eliminated?

Absolutely not. There was no chance for this because the post-war regime did not integrate but excluded. It is true that, to some extent, it united society – around the idea of rebuilding the city or certain socio-economic ideas. At the same time, however, it made the society even more disintegrated – excluded entire social groups from participating in the construction of the new reality. I mean, for example, the persecution of former soldiers of the Home Army, National Armed Forces and all those who did not fit within the recognized framework of military activity during the war and who continued this fight after the war. In addition, the authorities created a symbolic wall between the country and emigration.

Another exclusion resulted from the economic and political changes themselves. By nationalizing industrial plants, the Communist authorities finished off what had been the fabric of the city, i.e. small business. From 1947, it was systematically destroyed in various ways – by taxes, malicious controls, and public persecutions. As a result, the private sector shrank significantly. People tried to organize their lives on their own, but the regime did not like people being independent, it tried to integrate society by force, on the basis of collectivism.

Are the contemporary problems of Warsaw an effect of the fact that this community has not been rebuilt? Or maybe it never really existed?

At the very beginning, that is still in the Middle Ages, the community certainly existed. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Warsaw was a small city, and everyone knew each other. This, too, survived to some extent even until the 19th century. As a result of two wars, the occupation and the rule of the communist regime, however, this community was almost completely destroyed, it fell apart. What happened during the Polish People’s Republic, to a large extent, affects us to this day – I mean mainly property matters, but not only. The inept re-privatization resulted in many misfortunes and human tragedies. There is a heritage of history, but also of municipal institutions that failed to cope with the problems faced by the city and its inhabitants in today’s free Poland.

The symbol of the Communist era was the reconstruction of the Royal Castle, called by Edward Gierek “a document of the durability, independence and pride of the Polish nation”. What was the significance of the reconstruction of the Castle for the authorities and for the citizens?

The authorities of the People’s Republic of Poland initiated the reconstruction of the Castle in order to mobilize citizens from below for certain actions, which they could then use for their propaganda purposes. A significant part of the inhabitants of Warsaw, especially those who remembered it from the pre-war period, wanted this reconstruction very much. Therefore, it was greeted with joy and hope, seen as an announcement of changes after the rules of Gomułka, who was not very much liked. In this way, the Warsaw authorities managed to revive the myth of reconstruction, which had hardly advanced since the end of the 1950s.

The reconstruction of the Royal Castle was extremely symbolic. It brought a part of tradition to the reality saturated with the propaganda of modernity, which already in the 1960s began to tire the inhabitants of Warsaw, causing a certain dissatisfaction. Because modernity was, in a sense, unfulfilled. The castle, on the other hand, was completely fulfilled and at the same time a very successful recreation of the past. With its help, the authorities tried to reconcile the past with the present and the future, create a certain continuity of history and convince citizens that they lived in a place that had both the splendor of the past and great prospects for the future.

Was it successful?

Not at all, because there was a serious crisis that significantly changed the situation in the city. In 1977, when Plac Zamkowy gained its new shape, everything else lost its shape. The falsehood of propaganda and the crisis grew. There was a shortage of basic products in stores, and the prices of what you could get were high. In addition, at the end of 1978 and at the beginning of 1979, there was the so-called winter of the century – heating in apartments stopped working, coal supplies almost finished completely, and there was a fear that there would be a shortage of food and people would starve. In the 20th century, in the center of Europe, an existential threat appeared that corresponded to the times of great wars or epidemics.

Solidarity, established two years later, explained why this happened: there was no subjectivity and no right to govern independently. Thus history made a circle – exactly the same explanation was given by the elites of 19th-century Warsaw, deprived of self-government by the invader. After the fall of the Polish People’s Republic, however, the capital regained self-governance. Today, we can no longer look for external responsibility for the internal problems the city struggles with.

What does the history of Warsaw tell us about the contemporary capital? Which period has shaped its contemporary image and the identity of the Varsovians to the greatest extent?

It is difficult to say what the identity of Warsaw inhabitants is today. In the past, it was much easier – the craftsman owned a workshop that he inherited from his parents, then he passed it on to his son and this is how it looked from generation to generation. People lived within a certain territorial community and in this sense their identity was strongly associated with the place. Today, when people migrate, or change their place of work and place of residence, this identity is much more difficult to grasp. But I think it is anchored in a different way. Everyone works somewhere, has a family, friends, and struggles with some problems – the identity of the city and Warsaw residents rather results from this type of relationship.

Perhaps they also have some symbols in common. We have, for example, the typical Warsaw emblem of Fighting Poland or insurgent armbands. In principle, they integrate society, unite it around the idea of heroism or common struggle. However, these are only symbols – I have the impression that, unfortunately, they are more and more empty. Do they say anything about the identity of the Varsovians?

Interviewer: Natalia Pochroń

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin