Wanda Rutkiewicz was one of the best Himalayan climbers in history and a pioneer of all-female climbing in the world’s highest mountains. She climbed eight eight-thousanders. She always looked at Himalayan mountaineering through the prism of sport. She pushed her own limits, wanted to be the best every time, and never gave up on the goals she set for herself. What were the life and mountaineering achievements of this Himalayan climber who surpassed men and became the first citizen of her country to stand on top of Mount Everest and K2?

Emulating male role models

She was born in Plungė, Lithuania on 4 February 1943. After the war, her family came to Poland and settled permanently in Wrocław. Her mother Maria did not work professionally and was a housewife. It was her father Zbigniew Błaszkiewicz – an engineer, designer, polyglot, swimmer, sharpshooter and judoka – who, from an early age, shaped the character of his daughter, who always tried to catch up with male role models. Already in primary school, Wanda was very ambitious. She always wanted to be the best, both in the classroom and in sport. Perhaps she wanted to prove to her father that she could replace his first-born son Jurek, whose body had been torn apart by an unexploded bomb in 1948, in front of her five-year-old sister. They were very similar: they shared the same drive for life, willingness to take on challenges, and imagination.

After graduating from the Wrocław University of Technology, Wanda began working at the Institute of Power Systems Automation, and before the age of thirty, she moved to the capital, where she worked at the Institute of Mathematical Machines. Before focusing on climbing, she trained track and field sports in secondary school, and then successfully played volleyball for many years. She played in the first league in the team Gwardia Wrocław. She was even in the more expansive formation of the Polish national team.

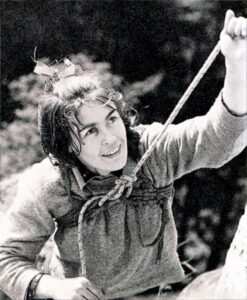

Through the Wrocław High-Mountain Club and Sokoliki in the Sudety Mountains, she soon found her way to the Tatra Mountains, where she completed a mountaineering course in 1962. The beautiful young girl made a breakthrough into the male-dominated environment. Andrzej Zawada, leader of Polish Himalayan expeditions, recalled that ‘at first, nobody realised that this calm girl, who appeared to be slightly from a different era, had an iron character, enormous willpower, and could be extremely disciplined in her actions’. She aimed high from the very start, wanting to match her stronger colleagues. She loved adventure and challenges. She was a volcano of energy, unable to sit still. At the same time, she did not listen to anyone and was aware that she often took risks in the mountains: ‘If I am playing with death, then apparently I need to’.

Her first climbing partner and fellow student Bogdan Jankowski recalled that she was always well prepared athletically, but had a weaker psyche in the beginning. However, she overcame her fears with stubbornness, determination and ambition, qualities that were in her blood. She did not compromise, she wanted to dominate even in mixed teams: ‘She wanted more and more all the time. It was never enough for her. She was happy when she achieved something, and tried to prolong this happiness with subsequent summits.’

From the highest Polish mountains back in the 1960s, she ended up in the Alps. She climbed, among others, Mont Blanc, Eiger and the Matterhorn. In 1970, she climbed Lenin Peak in Pamir, which was her first seven-thousander. Before focusing her mountaineering activities on the world’s highest mountains, she climbed the eastern pillar of the Trollryggen wall (Troll Wall) in Norway and Noshaq (7,492 m) in the Afghan Hindu Kush.

Wanda Błaszkiewicz was likeable, smiling, easily made friends, but also had problems building deeper relationships. In 1970, she married Wojciech Rutkiewicz, with whom she soon separated. In 1982, she married Helmut Scharfetter, an Austrian physician. However, this relationship also quickly fell apart. As Janusz Onyszkiewicz, an opposition activist, politician, and long-time president of the Polish Mountaineering Association, recalled: ‘For Wanda, the mountains came first and all female-male matters were subordinated to this (…). Her greatest love was always the mountains. She made up for everything with her determination. She never allowed herself to make any concessions. Had she sensed they were suggested, she would have rejected not being treated on an equal footing. This would have been a blow to her.’ In her own words, it was an incurable disease: ‘I fell in love with mountaineering. The starting point is love, and only later does a person wonder if it all makes sense.’ She also admitted that she was addicted to risk and danger. She lived from one expedition to the next. She spent all the money she earned on further expeditions. It must be admitted, however, that – due to her numerous foreign contacts – she had it a little easier than the other giants of the golden age of Polish Himalayan mountaineering, who had great difficulty in securing the budgets for subsequent expeditions.

The first Polish citizen to climb Mount Everest and K2

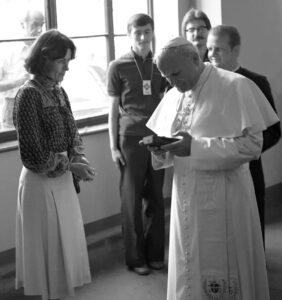

In 1975, she climbed Gasherbrum III and set the Polish female altitude record (7,946 m). She only became famous, however, for her ascent of Mount Everest on 16 October 1978. She participated in a German expedition climbing the world’s highest summit as the third woman in history, the first European, and – thus arousing the envy of her colleagues – the first Polish citizen. It was her first eight-thousander. That same day Karol Wojtyla was elected Pope and, already as John Paul II, addressed Rutkiewicz during his homecoming visit: ‘Apparently it was the good Lord’s wish that we both climb so high on the very same day.’

Just before the expedition began, she was not issued an athlete’s card because she had been diagnosed with anaemia. She travelled to Nepal at her own risk with a supply of injections and, fortunately for Himalayan mountaineering, managed to combat the illness and normalise her haemoglobin levels.

When asked after her return about the male participants of the expedition, she said that she ‘could not count on any concessions’, and that her companions were likely ‘somewhat irritated by the fact that a woman was able to endure what young and strong men could barely endure’. In a Polish Radio studio, however, she concluded the broadcast by addressing the audience: ‘I wish for all those listening to me to achieve their Mount Everests in life’.

After this success, she became very popular in Poland. She wrote books, gave interviews, and appeared on television. She took unpaid leave from work. She lived the life she wanted; she was free. She often travelled abroad. In grey communist Poland, such a life was a luxury. She wanted to follow her dreams, and she said that ‘if you want something very much in life, you dream about it, you can always have it’.

Before setting foot on yet another eight-thousander in July of 1985 (Nanga Parbat in a women’s expedition), she struggled for a long time with the consequences of an open femur fracture she suffered near Elbrus in 1981, when a skier bumped into her and they tumbled two hundred metres together down a slope. During her rehabilitation in Innsbruck, she exercised so intensely that she suffered a repeated fracture. In 1982, still not in top shape, she led an unsuccessful women’s expedition to K2, during which another outstanding Polish mountaineer, Halina Krüger-Syrokomska, died. She reached the base camp at 5,000 metres above sea level moving on crutches, with a splint in her leg, aided by painkillers. She walked more than a hundred kilometres. For a while, she was carried on the back of Jerzy Kukuczka, another great Polish Himalayan climber. The unusual sight of Wanda traversing the Baltoro Glacier on crutches became embedded in the memory of the local carriers, who remembered the ‘crazy Polish woman’ for a long time to come.

In 1984, she tried her hand at K2 for the second time. She succeeded only on her third attempt. On 23 June 1986, her name day, she became the first woman and the first Pole in history to stand atop K2, considered the world’s most difficult mountain to climb. During that season, up to thirteen people died in their attempts to reach the summit, including the French Barrard couple, with whom she had climbed. Wanda arrived at the base camp barely alive, returning alone, in a heavy snowstorm, and reportedly ‘looking as if from the moon’. This was the greatest achievement of her mountaineering career.

Although she was a great character, she was not a born leader, and eventually abandoned the idea of all-female expeditions. Her partners had numerous objections to her behaviour during trips. She repeatedly put her life at risk and demanded the same of others. In doing so, she was often a danger to her female companions, who she burdened with challenges inadequate to their capabilities.

A caravan of dreams

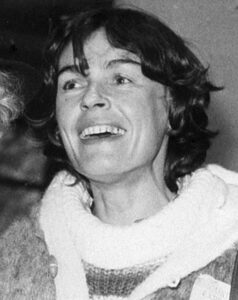

Rutkiewicz professionalised her sporting activities in the second half of the 1980s. She had her own agent, which was unique in Polish climbing circles, and from then on it was easier for her to raise money for expeditions. As part of her ‘dream caravan’ project, she intended to climb, as the first woman, all fourteen eight-thousanders, i.e. the Crown of the Himalayas and Karakorum. Between 1987 and 1991, she succeeded in climbing five more: Shishapangma, Gasherbrum II, Gasherbrum I, Cho Oyu and Annapurna. However, her idea was quite controversial. In the final phase, she seriously accelerated and aimed to climb the missing summits by the end of 1993.

Colleagues argued that, given the planned pace, as well as her age, the project was impossible to carry out. Furthermore, some in the community questioned the veracity of Wanda’s ascent of Annapurna. A special commission was even set up, which eventually confirmed the summit had been reached. Rutkiewicz was never fast in the highest parts of the Himalayas. However, in the final few years of her activity, she became noticeably weaker and slower, hence she had problems in choosing suitable partners. Incidentally, she repeatedly experienced health problems in the Himalayas – hallucinations and impaired consciousness – and, constantly bothered by the splint in her thigh, she took strong painkillers and sleeping pills.

The Himalayan mountaineer Krzysztof Wielicki, who had climbed Annapurna with Wanda, claims that his colleague ‘was running in a tunnel that narrowed, narrowed and narrowed, and everyone feared that it must end badly’. She sought solitude in the mountains and often cut herself off from the team. She began to live in her own world. Her colleagues saw her actions as an attempt at self-destruction. In any case, the stigma of death hovered over Rutkiewicz throughout her life. First her brother died. Then her father was murdered in 1972. She lost many climbing partners during her mountain expeditions. She was very much affected by the death of Kukuczka in 1989. A year later, Wanda’s last love, the German physician Kurt Lyncke-Krüger, died. She took his death very badly; she was said to have been truly in love at last. He died in front of her eyes. He stumbled on a slope and, when she reached him, was already dead.

However, she did not stop chasing her dreams and, two years later, she may well have stood at the top of her ninth eight-thousander. We will never know. The Himalayan climber disappeared whilst attempting to climb to the top of Kanchenjunga. She was forty-nine years old. She was last seen on 12 May 1992 at an altitude of around 8,300 metres above sea level, and was left alone in the ‘death zone’. Together with Carlos Carsolio, she was due to go for the summit. She grew weak. The Mexican climbed to the top and started to descend. The Pole decided to make a solo attempt….

Despite her evident physical weakness in her 40s, she always set ambitious goals for herself and did not let up until the end of her life. In her own words: ‘What annoys people most is that we risk our lives for something that appears completely useless and unnecessary to anyone. But perhaps it is needed by those who do it. Perhaps they just need it in order to live.’ She believed that she would always combat the malaise. She was repeatedly nonchalant about her own body. She lived on the edge.

The body of the world’s first lady of Himalayan mountaineering was never found. Her mother believed until the end of her life that her daughter had abandoned the western world for a peaceful life in one of the Buddhist monasteries.

The story of Wanda Rutkiewicz is, on the one hand, a tale of self-destruction and, on the other, a story of how – through strength of will, ambition, and great determination – dreams can be fulfilled and goals achieved.

The Polish Sejm has proclaimed 2022 as the Year of Wanda Rutkiewicz.

Author: Piotr Bejrowski

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki