Walery Sławek, conspirator, intelligence officer, and thrice Poland’s prime minister. When a bomb exploded in his hands, he lost his left eye, the hearing in one ear and several fingers. Two years later, his fiancée died, leaving him a bachelor until the end of his days. As a politician, he used to say that “it is healthier to sometimes break the bones of one deputy rather than be forced to use machine guns.”

Mikołaj Mirowski interviews Professor Paweł Samuś, author of the book Walery Sławek. Droga do niepodległej Polski (Walery Sławek: The Road to an Independent Poland) on the 81st anniversary of the suicide of Marshal Jozef Piłsudski’s closest aide.

Mikołaj Mirowski: Walery Sławek is a somewhat forgotten figure today.

Paweł Samuś: He is worth remembering, though, because he was a true individual, an extraordinary figure who served Poland devotedly. This man was the personification of total devotion to the idea and cause of independence. He was a symbol of moral purity, as well as a politician known for selflessness and righteousness in public life. Although the name Walery Sławek often appears in historical literature dedicated to the modern history of Poland, he is not well known to the wider public.

Could you tell us about his family background?

Walery Sławek was born 2 November 1879 in the village of Strutynka in the Kiev province, to an impoverished Polish noble family. His parents, Bolesław Sławek and Florentyna née Przybylski, came from the families of the Polish nobility living on the border with what is now Ukraine. Walery Sławek had three sisters, and he grew up in an atmosphere of fervent patriotism. His father, a clerk at the sugar factory, devoted himself to the education and spreading of a Polish patriotic spirit among the local population.

Sławek graduated from grammar school in Niemirów, and then from the renowned Leopold Kronenberg School of Economics in Warsaw where he also attended the underground lessons known as the Flying University. He was an educated man.

He quickly became a conspirator and, despite his good education, was more of a “practitioner” than a “theoretician”.

At the beginning of 1900, he started working in Łódź as the head of the insurance department of one of the companies there, and later took a position at a bank (Bank Handlowy) in Łódź. Soon he made contact with activists from the Polish Socialist Party, joined the workers’ community in Łódź and took part in their underground activity. He distributed leaflets, organized party meetings, and gave lectures. After more than a dozen months, and threatened with detention, he quit his job at the bank and devoted himself to the Polish Socialist Party as a co-conspirator.

He was the lead organizer in various centers of the Kingdom of Poland. In 1902, he became a member of the Central Executive Committee of the Polish Socialist Party, and operated under various pseudonyms, most often as “Gustaw”. He was arrested for the first time in March 1903, and was first imprisoned in Piotrków Trybunalski, and later in Sieradz. After a daring escape at the end of the year, he continued his illegal activity in the Russian partition.

Sławek was a co-creator of the paramilitary organization of the Polish Socialist Party, heading it after the outbreak of the 1905 revolution. In June 1906 at Milanówek, after an unfortunate accident, he was seriously injured, detained by the tsarist police, and threatened with the highest sentence. However, he was eventually was released from prison after six months and managed to cross the Austrian border and take refuge in Kraków.

In Galicja, Poland’s southern region, also known as the “Polish Piedmont”, Sławek undertook a long course of treatment and recovery. He also became a supporter of the modified concept of Polish irredentism and one of Piłsudski’s closest associates. He devotedly supported Piłsudski’s efforts to prepare Poland to fight for independence and to create the nucleus of the armed forces. He played a very important role in establishing the paramilitary organization Związek Walki Czynnej (Union of Active Struggle) as well as training its riflemen. He also organized the Polish Military Treasury and managed its activities.

When the First World War broke out, he participated in the formation of the riflemen brigades which were entering the Kingdom of Poland. He led the 1st Brigade of the Polish Legions, participated in its epic fights on the front, and was active as an officer of intelligence activities. In August 1915, delegated by Piłsudski to a Warsaw that was occupied by the Germans, he lead the Kingdom of Poland’s resistance, and was one of the leaders of the Polish Military Organization.

In July 1917, captured by the German police, he was imprisoned in the Warsaw Citadel and then detained at camps in Szczypiorno, and later in Modlin. In the fortress in Modlin, he managed to conduct the disarmament of the Germans, and on 12 November 1918, he returned to Warsaw.

Later, during the interwar period, Walery Sławek undertook a military career…

Initially, he became the General Adjutant to the Commander-in-Chief Józef Piłsudski, and devoted himself to serving in the Polish Army. He held high positions in the General Staff, during the fighting over territory along the eastern borders of the reborn Polish state, carried out political missions, and served in the headquarters of several fronts. At the end of 1923, as a qualified lieutenant colonel, just like Piłsudski, he left the army.

One of the most interesting incidents took place in January 1920, when Sławek came to Ukraine to take command of the Southern Front, and at the same time negotiated the terms of an alliance with Semen Petlura, a representative of the Ukrainian People’s Republic. What kind of military man was he?

Sławek performed more special missions at that time. As I mentioned, he began his service in November 1918, as the General Adjutant of the Commander-in-Chief.

Soon, he was delegated to head the Bureau of Intelligence of the Polish General Staff, and in April 1919 he commanded one of the groups liberating Vilnius. In May, he became the head of the division of the Lithuanian-Belarusian Front, and nine months later he assumed command of the division of the Southern Front.

He performed all of his tasks very well which is why he was entrusted with increasingly more difficult intelligence and negotiation assignments. And the alliance with Semen Petlura was key to Piłsudski’s concept of creating independent federal states on Poland’s eastern border! In addition, he participated in talks with the Lithuanian and Latvian authorities in order to settle outstanding issues and establish political and military cooperation.

In May 1920, during the Kiev expedition, he was promoted to the rank of major, and became the Chief of Staff in Ukraine. In the autumn he organized Polish-Ukrainian volunteer troops as a lieutenant colonel.

After the war, he served as an officer to the Commander-in-Chief. In December 1922, he was directed to a one-year training course at Wyższa Szkoła Wojskowa (the College of War), and obtained the diploma of an officer of the General Staff. We can say without hesitation that he had a professional career in the army.

After the May Coup of 1926, he returned briefly to active military service, but above all he was active in politics. At that time, Piłsudski needed him most in this role.

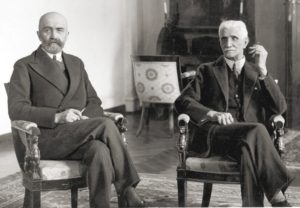

Sławek was one of Piłsudski’s most trusted people, and he also enjoyed his sincere friendship. When in 1924, Piłsudski gave him a copy of his book Rok 1920 (The Year 1920) for Christmas, he wrote: “Dear Gustaw![1] Just yesterday you were looking so irritated at me and I thought to myself how many times we have been irritated with each other. We are like two old horses, which often walk nearly impassable roads separately, and meet at a peaceful moment of their lives, greet each other and stand side by side to pull the same carriage.” What shape did their relationship assume over the years?

Walery Sławek first met Józef Piłsudski, the leader of the Polish Socialist Party, in Vilnius in May 1902, while taking care of some issues regarding the party. They were meeting quite frequently throughout the course of their activities for the underground, at some point longer conversations took place between them and a bond of mutual trust was established. However, there was quite a significant age difference between them, as Piłsudski was twelve years older than Sławek.

When Sławek was recovering in a hospital in Kraków in 1906 after a serious accident, he was visited by Piłsudski on Christmas Eve, and the Marshal later spent the whole evening with Sławek’s family in their apartment. During this time, after having undergone several major surgical operations over the course of two years, Sławek, who was in a bad mental state after the accident, was treated with great compassion by Piłsudski. The Marshal helped him overcome his depression and encouraged him to be more active.

During the times of the Legions they developed a close friendship. During the war this legendary and elite division became a unique community under the charismatic leadership of the Commander, and assumed responsibility for Poland despite the passive attitude of many Poles.

After regaining independence, Sławek remained Piłsudski’s friend. He was his most devoted assistant and always carried out Piłsudski’s tasks diligently. Their contact was frequent, and they were great friends. Piłsudski, by entrusting Sławek with a “special” task or an important mission, could be certain that it would be carried out faithfully.

I would like to come back to the “serious accident” you mentioned. In preparation for one of the actions of the paramilitary organization in June 1906, a bomb exploded while Sławek was holding it in his hands. He lost his left eye, his hearing in one ear, several fingers, and his face, chest and both hands were wounded. Soon after, he was hit by a personal tragedy – his great love, 19-year-old Wanda Juszkiewiczówna, died. Did such traumatic events leave a lasting mark on his character?

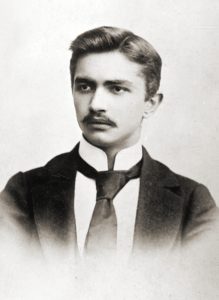

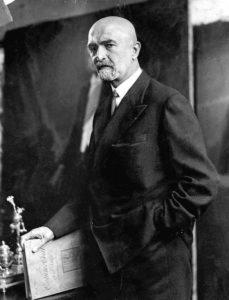

It is worth recalling that in his youth, before the accident with the bomb, Sławek was a very handsome man, tall and slender; he had a face with delicate features, nicely shaped lips, a mustache, straight nose, black eyes and dark hair, over time he grew a beard. He was modest, gentle, charming, rather shy towards people, women liked him, and he was liked by his colleagues.

Mutilated after the bomb exploded, and also bearing a wounded psyche, he avoided social contact for some time. After recovery, his scars healed – although he partially covered them by growing a beard – but he had to come to terms with the permanent effect of his disability. However, he quickly regained the ability to live and work normally, as well as his physical charm, and this improved his well-being.

His psyche was undoubtedly influenced by many years of underground activity, the ruthless conspiracy habits developed at that time to some extent were visible when he became a politician in the interwar period.

Wanda Juszkiewiczówna, the only daughter of Maria Piłsudska from her first marriage, was Józef Piłsudski’s stepdaughter. According to recollections, she captivated everyone with her extraordinary beauty. Sławek met her during his first meeting with Piłsudski in Vilnius, and then again when he often visited Piłsudski in Kraków. They are said to have fallen in love with each other, and Wanda reportedly became Sławek’s fiancée.

In August 1908, at the age of 19, Juszkiewiczówna died of acute inflammation of the gallbladder. Her death was a tragic blow for Sławek, and had a permanent impact on his personal life – he never considered marrying again.

Walery Sławek, before becoming the head of Bezpartyjny Blok Współpracy z Rządem (Non-Party Block for Cooperation with the Government), was a co-author of the brochure (together with Adam Skwarczyński, Tadeusz Schaetzel, Kazimierz Świtalski and Tadeusz Hołówka), as well as a member of the „Konfederacja Ludzi Pracy” (“Union of Workers”) organization. Was he truly a socialist or was he rather a nationalist?

He was loyal to Piłsudski, but there were many people who were loyal to Piłsudski in various ways. In November 1918, for Sławek, like other representatives of the independence leftist camp, it was obvious that the national goals and the reconstruction of the state were most important, as well as the liberation and re-unification of Polish lands. He was also a statesman.

The “Union of Workers” mentioned by you, was a small group formed in 1924, they were representatives of the intelligentsia, most often from a leftist background. The creators of this program recognized the development of Poland as the supreme goal, called for strengthening the authority of the state, and urged that the elite that was about to emerge during the struggle for independence take responsibility for it.

The Union was established as an alternative proposal to the existing system, its founders, embittered by the failures of parliamentarianism, blamed the parties for bad solutions. They believed the country could be reborn thanks to work and creativity, and a new organization of society in accordance with the idea of self-government. These tasks were to be carried out by the intelligentsia.

After 1926, Sławek as the head of the Non-Party Block for Cooperation with the Government, and having served as prime minister three times, was considered the most important figure – after Piłsudski – of the interwar period. He became one of the architects of the new political system, and as a supporter of building a modern, strong state, he led the work on the new constitutional law, seeking to expand the president’s powers and strengthen the executive power; he was a co-author of t

Why did Sławek not assume power in Poland after Piłsudski’s death? Among all the followers of Piłsudski, he was much more influential and important than Ignacy Mościcki, President of Poland from 1926 to 1939, who was rightly said to be a figurehead, while Edward Rydz-Śmigły was supposed to be responsible for the army only, as Józef Beck was for diplomacy. Still, the reasons for Sławek’s spectacular political decline are difficult to explain.

Sławek’s defeat was undoubtedly a great surprise for observers of political life at the time. After the adoption of the new constitution and after Piłsudski’s death in May 1935, Prime Minister Sławek was considered to be the number one person in the state. He was an obvious candidate for the office of the President of the Republic of Poland, and was also Piłsudski’s chosen successor, according to a secret order known only to the Marshal’s closest associates. However, Ignacy Mościcki refused to step down, and was supported by liberals from the so-called Castle group, as the Royal Castle in Warsaw served as the residence of the Polish president, and the team of the General Commander of the Polish Armed Forces Edward Śmigły-Rydz, which initiated a split between members of the May Coup group.

Walery Sławek was surprised and decided not to remove his competitor. He was convinced that “the law, as the supreme regulator, is supposed to rule us, meaning that the one who rules is designated by this law”. He had no support among members of the group of Colonels either. After the boycott of the parliamentary election by the opposition, he resigned from the office of the prime minister in October 1935 and, in what would turn out to be a serious political error, dissolved the Non-Party Block for Cooperation with the Government.

Depressed after the death of Piłsudski, resentful of defeat, pushed aside and harassed by political competitors from the ruling camp, he withdrew from political life, returning only briefly when he was elected Speaker of the Sejm (parliament) in June 1938. Nevertheless, in the November elections he was eradicated by his opponents and failed to obtain a seat in the parliament. After 1936, he only served the president of the Józef Piłsudski Institute, edited his memoirs and gave lectures.

Sławek was an honest man, he did not make a fortune while holding the power. So how did he reconcile this personal honesty with the brutality he presented in politics? His statement is well known that “it is healthier to sometimes break the bones of one deputy than to be forced to use machine guns.” On the other hand, when asked about the fate of oppositionists imprisoned in the Brest fortress, he replied that “those who fought for Poland, not against it, were kept in much heavier prison conditions.” But those were the prisons of the Tsar regime. Is there any logic in it?

Sławek has indeed become a model of moral purity in public life, the personification of an honest, modest man, leading an almost rough lifestyle, and not seeking money while performing the highest state offices. Even his political opponents emphasized that he was an idealist, although they could not forgive him some of his harsh public statements and his actions against the opposition.

The words you quoted from Walery Sławek belong to his typical rhetoric and public statements at a time of political struggle in the country, when as the leader of the ruling group of the May Coup, and a supporter of the authoritarian rule, he had not yet managed to push through constitutional changes.

Sławek’s harsh statements about opponents are also known from disputes with the parties forming the liberal block and after the parliamentary elections in 1930. Is there logic in it? Sławek would probably think that there was, because, in his opinion, he acted so only for the good of the state.

However, the biggest secret of Sławek’s biography is the matter of his suicide. Its causes are still one of the biggest mysteries of the Second Polish Republic. Many historians and writers have had various suggestive hypotheses. Beginning with increasing depression, through to the idea of an alliance with Hitler, in order to protect the Second Polish Republic, and ending with a plot and an attempt to poison Ignacy Mościcki. The most fantastic theories (indicating that they cannot be verified in the light of the available documents) were presented by Dariusz Baliszewski, the author of the TV show „Rewizja nadzwyczajna” (“Extraordinary Review”). What do we know about it for sure?

Unfortunately not much. We know his short farewell letter, in which he stated that no one was to be held responsible for his death, we also know that he held the barrel of his old browning, which he had used years ago, pointing it at himself at 20.45, i.e. at the time of Piłsudski’s death. He died in the hospital the next day.

The news of Sławek’s suicide rocked public opinion. His contemporaries, as well as historians and writers formulated various more or less sensible hypotheses about its cause; they were pointing to, for example, a mysterious phone call or a telegram that he was supposed to have received on Sunday morning, 2 April, after which he took his life in the evening, while others pointed his increasing depression.

This puzzle has not been solved yet and I believe the circumstances of Walery Sławek’s death will never be fully revealed. It is only guesswork, and a historian should not take part in it without credible evidence. On 5 April 1939, on the day of Sławek’s funeral at the Powązki Military Cemetery in Warsaw, the Vilnius newspaper “Słowo” wrote: “Next to the myth of the struggle for independence of Poland known to us, another myth has appeared. The myth of the mysterious life and death of Walery Sławek. He did not blame anyone, this man of no private life” – this sentence seems the perfect coda for his biography.

[1] Gustaw – pseudonym of Walery Sławek.

Interviewer: Mikołaj Mirowski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin