When the Germans invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, these two men called upon Polish Jews to fight. Then they attacked Stalin and paid the ultimate price. Up to this day, the deaths of Wiktor Alter and Henryk Erlich, leaders and activists of the General Jewish Labour Bund, a Polish Jewish socialist party, are among those events in Poland’s 20th-century history that still need clarification.

by Mikołaj Mirowski

Almost 80 years ago, these deaths reverberated widely throughout the West and resulted in strong criticism of Soviet actions with regards to Poland and its citizens. Only the Katyn massacre, revealed by the Germans in 1943, resulted in a greater diplomatic upheaval.

Socialists from an early age

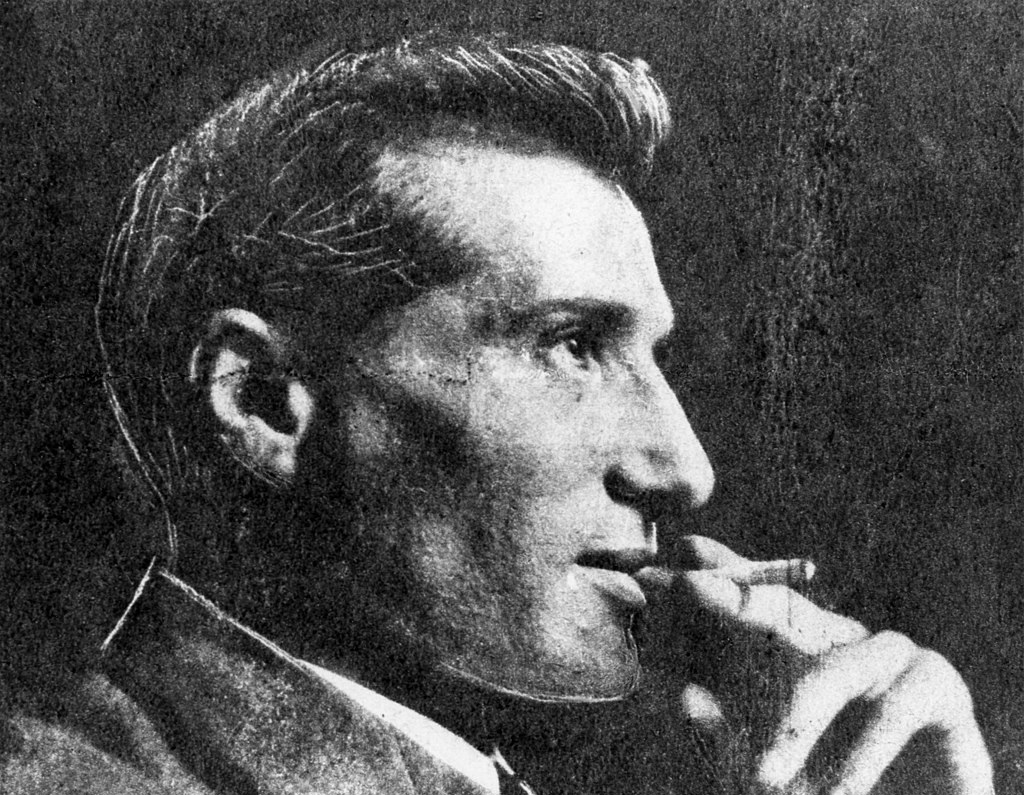

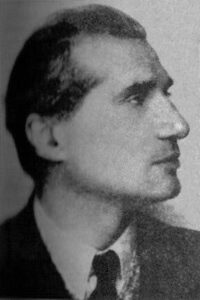

In the interwar period, Wiktor Alter and Henryk Erlich were both well-known activists in the Jewish socialist workers’ party General Jewish Labour Bund. On its recommendation, they served as Warsaw councilors for many years. Alter was also a journalist, and was published in Polish and Yiddish (as an editor of, among others, “Nowe Życie” and “Di Naje Folkscajtung”). He was also the author of brochures and books, the titles of which reveal the scope of his interests: “Der emes wegn Palestine” (“The truth about Palestine” – a critique of the Zionists), “Fighting Socialism”, “When the Socialists Come to Power …!”, “Economic Anti-Semitism in the Light of Numbers”, “Cu der jidn-frage in Pojln” (“About the Jewish Question in Poland”), and “Man in Society”. In turn, Erlich, a well-known lawyer, was active in the Association of Socialist Lawyers.

Founded in 1897, the General Jewish Labour Bund advocated that Jews should stay in the countries where they lived rather than emigrate to Palestine. Both Alter and Erlich had been associated with this party and its position since the beginning of their political activity.

Alter was born in 1890 in Mława. He took part in a student strike as a 15-year-old student in Warsaw and a Bund member; as a result, he was forced to leave the territory of the Russian partition for the West. He returned in 1912 and became involved in the party’s affairs, a year later he was arrested by the tsarist authorities and, like many of his comrades, exiled to Siberia. He managed to escape and go to Great Britain, where, during the First World War, he joined the ranks of the local Labour Party.

Erlich, eight years older (and a native of Lublin), was a law student at the University of Warsaw; and had joined the Bund at the age of 21,. A year later, he was imprisoned for the first time for several months. Once released, he decided to go to Berlin, but he returned to Warsaw to participate in the revolution of 1905. Threatened with arrest, he went to St. Petersburg, where he graduated law. He would subsequently be promoted in the party; from 1913 onwards he belonged to the Bund Central Committee. Four years later, Alter also found himself in the party’s governing body.

Against the Bolsheviks

Their paths crossed for the first time in Russia in 1917, as the country was rife with chaos. Erlich became the Bund’s representative in the Council of Workers’ Delegates in Petrograd (the German name of the Russian capital was changed after the outbreak of the First World War). However, when the Bolsheviks seized power through a coup, Erlich, who did not accept these methods, decided to go to Poland.

Alter stayed in Russia and, in July 1918, took part in the Workers’ Delegates Conference, the participants of which were arrested by the Bolsheviks. Released after a few months, and knowing what Lenin and his cadre were capable of, he also managed to travel to Warsaw. He found himself in Soviet Russia for a while in 1921 – as a member of the two-person delegation of the Bund Central Committee at the Third Congress of the Comintern (an organization created to promote the idea of revolution throughout the world). There he was arrested once again – and luckily released again after 10 days, thanks to protests of other congress participants.

It must be admitted that already at that time Alter and Erlich – although both possessing radical leftist views – were opponents of the Bolsheviks and the Soviet authorities. This was reflected in the attitude of the Polish Bund, which became an independent entity in 1915 (it remained so until 1948, when it was dissolved following the Yalta conference).

In 1917, the Bund supported the February Revolution which overthrew the Tsar and brought a democratic government to power, but it showed no enthusiasm for the autumn Bolshevik coup. The latter caused a division in the party, resulting in the separation of the so-called Kombundu – its representatives joined the Communist Workers’ Party of Poland in 1923 (known since 1925 as the Communist Party of Poland), which in the Second Polish Republic assumed the role of Bolshevik agents.

Over time, the ideological profile of the Polish Bund drifted further and further away from pro-communist or pro-Catholic sympathies. In the Second Polish Republic, the Bund, despite initial differences about ideas regarding Poland’s independence, cooperated more and more closely with the Polish Socialist Party. In 1927, Erlich published an article in which he unequivocally criticized Soviets for having betrayed the tenets of socialism.

Pulling away the Jewish recruit

When trying to understand the philosophy of the Bund, it is important to know that there were attempts at “allied” talks with the CPP in 1934. A year earlier, Adolf Hitler had come to power in Germany and, according to the recommendations of the Comintern, European communists needed to create an anti-fascist “people’s front”. The Bund negotiations were conducted by Alter, Erlich and Emanuel Nowogródzki. However, they ended in a fiasco as the communists were setting conditions which the Bund could not meet.

In a pamphlet published at that time, Alter wrote that the system of the Soviet Union was “the dictatorship of the party, reduced to the dictatorship of one person,” that is, Joseph Stalin, and this was unacceptable to socialists. In turn, when describing the Great Terror of the 1930s, Alter wrote about “the frenzy of bloody executions.” Meanwhile, many left-wing intellectuals in the West at the time tried to ignore Stalinist crimes.

Was it at that moment that these two Bund activists were first targeted by Stalin? Is this why a few years later he would be so tough and uncompromising towards them?

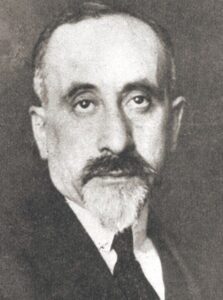

The reasons for this state of affairs were well explained by the journalist and writer Ksawery Pruszyński. In the story “Two Men”, devoted to Erlich and Alter (and published after the war in exile), he stated that “Moscow looked at the masses of the Jewish proletariat in Poland and around the world as property – potential recruits and a continual source of recruits. Diverting a recruit to another enlistment was considered a crime. And Jewish recruits were being dragged away by Alter and Erlich on behalf of the Bund. If the Jewish laborer was not a communist, it was because Alter and Erlich were able to explain to him that the light they were seeing in the east was not the aurora of true socialism (…). Maybe there is nothing surprising that from the Soviet point of view, Alter and Erlich were among the most dangerous people in Poland, and maybe not only in Poland? ”

Despite anti-Semitism

In the Second Polish Republic, Alter and Erlich became the most important leaders of the Jewish socialists, and the Bund – in alliance with the Polish Socialist Party – became an important element of the parliamentary system. In the late 1930s, it even started to win “on the Jewish street” with other parties – mainly the Zionist ones (regardless of whether they were left or right-wing). Alter and Erlich emphasized that Jews already had a homeland and that it was the country where they lived. Poland was the country in whichre they should fight for their rights as well as for the well-being of the society they belonged to. Their goal was the acculturation Polish Jews and the equalization of their economic and social opportunities, especially in order to help workers.

They insisted on this idea despite the anti-Semitism which intensified in the Second Polish Republic after Józef Piłsudski’s death in 1935. The experiences of the late 1930s did not cause the Bund to turn away from the Polish state. The question of its independence remained important to the Jewish socialists. When the Germans attacked on 1 September 1939, Alter and Erlich issued a proclamation calling on Polish Jews to fight.

During the German invasion in September, tens of thousands of soldiers of Jewish origin fought in the ranks of the Polish Army; perhaps even one in ten killed in 1939 was a Polish Jew. On the other hand, in Warsaw, many Jews, including Bund members, became involved in volunteer units or in civil defense at the request of their councilors.

From the labor camp to Kuibyshev

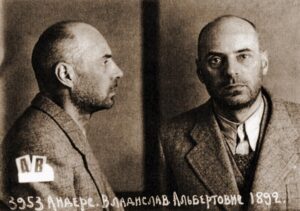

At the end of September, Alter found himself in Lida, in the Soviet occupation zone. Arrested by the NKVD, he was sentenced to death, which was then commuted to 10 years of exile. A similar fate befell Erlich. Arrested in Brest in early October, he was also sentenced to death, after which his sentence was changed into 10 years in a labor camp.

They were imprisoned in the Gulag for over a year and a half. When Hitler attacked his former ally in June 1941, the Polish and Soviet governments concluded an agreement on mutual aid in the war against the Third Reich. Called the Sikorski-Majski Pact (as it was signed by the ambassador to Great Britain, Ivan Mayski on the Soviet side), it also provided for amnesty for Polish citizens imprisoned in the Soviet Union.

Released from the labor camp in September, Erlich and Alter developed a project for the International Jewish Antifascist Committee. Erlich was to be at the forefront, and Alter was to be appointed secretary general. The Soviet authorities agreed, but – as historian Janusz Zawodny wrote – “they were surrounded on all sides with provocateurs”.

Both Bund members were sent to Kuybyshev – a city in the Novosibirsk Oblast, beyond the Ural Mountains, where a Polish embassy was established (in the face of the German offensive, diplomatic posts were evacuated from Moscow). Kuybyshev also became the headquarters of the reconstructed Polish army, headed by General Władysław Anders.

In Kuybyshev, Bund members established cooperation with Ambassador Stanisław Kot. It was an open secret that Kot’s enemies were gossiping that Alter and Erlich “ruled the embassy.” Such opinions, as Kot later recalled, “were unfortunately spread in the Polish Army by officers undoubtedly influenced by NKVD liaison officers, when these outstanding personalities were about to be killed. I was full of appreciation for Erlich’s reason and tact, [and] Alter’s courage and abilities, they helped me influence Polish Jews, and they advised me on many difficult issues.”

Agreement with Anders

Such was the case with the idea of acquiring Polish Jews for the reconstructed army. Bund leaders blocked ideas – formulated by the Zionist right – to form separate Jewish units with the intention of moving them to Palestine. Anders, in turn, undertook to eradicate manifestations of anti-Semitism and to treat all soldiers equally.

Following this informal agreement, Alter and Erlich issued an appeal: Polish Jews – former labor camp prisoners and other exiles who found themselves in the Soviet Union after 17 September 1939 – were encouraged to join Anders’ army.

They wrote: “We address all Jews, Polish citizens, capable of carrying weapons (…) with the appeal: To arms! Stand in the ranks of soldiers who, with their own blood, have the right to fight for free Poland once again. Who, together with the armies of the allied countries, want to free Poland and the whole world from the nightmare of Nazi captivity. Let those of you who are incapable of bearing arms should spare no effort to ease the Army’s fulfillment of its tasks to hasten victory. Participation in the current war for freedom is both an obligation and an honorable right. On behalf of the Jewish working masses and the Jewish intelligentsia who put their trust in us, we declare our readiness to fulfill the obligation and demand that we are able to exercise this right. ”

The loop tightens

Earlier, Alter and Erlich had refused to cooperate with the NKVD when establishing the International Jewish Antifascist Committee, which was of great importance to the Soviet authorities. They refused to accept becoming puppets. Moreover, they began to be interested in the fate of the missing – as it was still believed – officers of the Polish army, who in 1939 were sent to camps in Kozielsk, Starobielsk and Ostaszków. This enraged Stalin and was the reason for their next arrest.

The Bund members were aware that they were treading on thin ice, and therefore they sought permission to leave the Soviet Union. Erlich wanted to go to the USA, and Alter to London, where he intended to become a member of the National Council (parliament in exile) as a representative of the Jewish population to the Polish government.

They did not make it. On 4 December 1941, they were arrested in the evening. Alter’s son then claimed that the immediate cause was a letter from his father to Walter Citrine, head of the International Federation of Trade Unions, which the NKVD intercepted. Supposedly, the key fragment said: “For two years I was examining the USSR through prison bars. I swore to myself that, if I was released, I would do anything to hasten the end of this terrible nightmare that suffocates the Soviet Union. And I want your help in this.”

When the Polish embassy intervened in defense of those arrested, it received a reply that they were “Hitler’s spies”. To another diplomatic note which argued that they were both Polish citizens, a laconic response came that the Soviet government “sees no grounds to change its position.” Ambassador Kot’s further efforts to release Bund members also ended in a fiasco. On 28 January 1942, the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs ( equivalent of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) ostentatiously returned the Polish passports of Alter and Erlich to the embassy, informing them that they were Soviet citizens and “no further inquiries regarding them by the Polish ambassador should take place.”

A symbolic grave

The circumstances of Erlich’s death have not been finally clarified to this day. It was only in February 1943 that the Soviet authorities reported that on 14 May 1942, he committed suicide in prison (some historians, including Szymon Rudnicki and Marian Turski, support this version). Perhaps, however, he might have been shot – just like Alter, who was murdered by the NKVD on 17 February 1943, although this date is also uncertain. There is a hypothesis that they were both convicted of alleged espionage and murdered shortly after their arrest.

Following the Yalta conference, all memory of them was to be erased in Poland. Alter’s rich legacy, books and articles were withdrawn from libraries and placed under censorship. Only one year before the fall of the Polish People’s Republic, thanks to the efforts of Marek Edelman – one of the commanders of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and also a Bund activist – a symbolic grave was erected for them. It happened on 17 April 1988 at the Jewish Cemetery at Okopowa street in Warsaw, two days before the 45th anniversary of the outbreak of the ghetto uprising. The authorities of the Polish People’s Republic tried to use this anniversary to gain credibility to the eyes of the West – thanks to this, two Bund members could at least obtain a symbolic memorial site.

Then communism collapsed. However, [all these years later] Alter and Erlich have still not regained their rightful position in Polish historical consciousness.

Author: Mikołaj Mirowski – a historian and journalist, he published Rewolucja permanentna Lwa Trockiego. Między teorią a praktyką, 2013 (The Permanent Revolution of Leon Trotsky. Between theory and practice), the volume of conversations Piłsudski (nie)znany. Historia i popkultura, 2018 ((Un)known Piłsudski. History and pop culture) and the volume of studies Polskie zwycięstwo 1920, 2020 (The Polish victory of 1920), together with Michał Kopczyński. He works at the Polish History Museum.

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin