Moving from little Belluno to Venice – was this a necessity for an ambitious painter of the Baroque era? Especially if we take into account the fact that his father was a local painter who used to paint the folds of cloaks worn by saints. Dolabella ended up in the workshop of Antonio Vassilacchi and could feast his eyes on Tintoretto’s purple. But is a transfer from Venice to Cracovia a similar guarantee of greatness?

by Wojciech Stanisławski

Tommaso took a chance. He left his paintings to the mercy of wars, frosts, perhaps not very sophisticated viewers, and finally fire (the last great fire, which destroyed almost the entire interior decoration of a church, took place in 1850 in Krakow). In return, he gained a permanent place in the history of the art of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The exhibition shows the painter’s oeuvre as much as the history of the fascination with italian art and culture in Poland. The Rome-Krakow axis, or, more broadly, the Italy-Republic of Poland relationship probably never gained strictly political significance, despite the desires of a few daydreamers. However, culturally, it was of great importance. It would be difficult to find another European country whose rulers, collectors and lawmakers, as well as poets, composers and painters, would be so intensely focused on the country beyond the Alps as in the case of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Undoubtedly, however, the 16th and 18th centuries were a time of special attention to Venice and the exhibition “Dolabella, the Venetian painter of the Vasa”, opened in mid-September at the Royal Castle in Warsaw, showcases this perfectly. In the first rooms, we can see Polish “Venetiophilia” at several levels. From Venice – glass from Murano and colorful majolica, travel boxes and the best works of typography of the time – came to Poland. The magnate’s son, upon returning to Lithuania, boasted – as a sign of the times and so understandable today – a quarantine certificate issued on 11 September 1578 by the Serenissima offices. The stitches of Venetian lace, from reticella to coralina, turn whiter, portable altars shine. Even the last king of Poland, Stanisław August Poniatowski, in the portrait by Jan Baptist Lampi, wished to be presented in a ribbon of the Order of the White Eagle, but also with a Venetian mask from the commedia dell’arte in his right hand. Taking into account the political circumstances surrounding the portrait’s creation (his recent romance with Tsarina Catherine, his helplessness in the face of the first partition of Poland, and the king’s weakness in pursuing a discreet, behind-the-scenes policy), this mask looks a bit more ambiguous than Poniatowski had intended. Of course, it also proves his weakness for Venetian culture.

What true intentions – and from whom – did the monarch conceal in the days of conspiratorial preparation of the Constitution, just before the next partition of the country?

For now, however, according to the time presented at the exhibition, we are in 1600. The Republic of Poland stretched from Silesia to Smolensk and the possibility of partitions would never occur to anyone. The lack of artists at court and in the capital could be painfully felt. This was particularly acute in a situation where King Sigismund III Vasa and his successor, Władysław IV Vasa, had serious ambitions to build a stronger than ever center of power and to promote it in a meaningful and eloquent way. Meanwhile, “baroque piety” demanded dramatized images of saints and blesseds that would appeal to the imagination, floating on stucco clouds on the vaults of churches.

Why was the trade in paintings so lively in 17th-century Europe? Polish kings, magnates and bishops spent a lot on the works of masters from Italy. The canvases of Giovanni di Monte I Jacopo Negretto are mentioned in the property inventory, and art historians can argue at will about their provenance. At the time, however, when new churches were being erected, “large-format” painters were especially needed, able to paint large canvases and decorate, in the technique of frescoes, semicircular lunette walls offering numerous challenges on perspective painting.

It began with a commission from King Sigismund III Vasa, undertaking the renovation of the chambers at the Wawel Royal Castle. He counted on the cooperation of Antonio Vassilacchi himself, but the latter delegated his most talented student instead. Tommaso Dolabella reached Wawel at that time, but the first twenty years of his career in Poland were primarily collaborations with religious orders which were abundant at that time: Dominicans, Cistercians (Mogiła abbey), Franciscans, Jesuits. Over time, when his fame reached religious houses and dignitaries outside of Krakow. Dolabella decorated Palace of the Kraków Bishops in Kielce as well as works for the Dominicans in Poznań.

The peak of his creative activities, however, fell in the 30s of the 17th century. It was then that he worked simultaneously for bishops, abbots and King Władysław IV Vasa, creating a series of votive paintings on his commission. At the same time, there are portraits – even (attributed to Dolabella, although the authorship is still discussed today) of a young Stanisław Tęczyński, with the superiority of a young peer looking from the canvas – and panoramas, such as the “Battle of Lepanto”, where there was enough space for galleys, cumulus, and a thanksgiving procession. One could half-jokingly say that with the choice of the “decade of triumph” Dolabella confirmed his rights to the title of “the painter of the Commonwealth”. Also in the case of the Republic of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the 1630s are considered the “Silver Age”, followed by the drama of raids, the Swedish aggression (known as the “deluge”), epidemics and collapses. Master Dolabella survived the Swedes, Cossacks and the epidemic, but the 1640s is the time when he relied more and more on his students, and his canvases were filled with the rigidity of gestures, schematic poses and the dark carmine of the twilight.

What can we see at the recently opened exhibition? At first, we are struck by the exhibition artistry. Dolabella, as it was said, practiced not only easel painting: he decorated the interiors of palaces and churches, and the most interesting fragments were those copied from narrow inter-pilaster spaces or from concave lunettes in which Baroque architecture was fond of. Some paintings were intended to fill even more complex surfaces, for which there are no precise terms. Visitors can observe in amazement the irregular polygons, ending in an ellipse arc, where the oval of the window or the altar “fell” – and can admire how the curvature of the saber, moon and robe was incorporated into it. It is particularly evident in the case of “The Descent from the Cross” from 1634, crowning the main altar of the Corpus Christi Church in Krakow, arranged in one of the main rooms. The framed ceiling are very impressive, probably painted for the needs of the Archconfraternity of Mercy in Krakow and completely transferred on a titanium scaffold to one of the exhibition interiors.

The rest of the exhibition is an opportunity to savor Baroque painting in large doses. There has not been a Tintoretto or Veronese retrospective in Poland for quite a time, so we have the opportunity to imagine it while looking at subsequent canvases full of movement, lace, folds of robes, darkness in which lesser virtues disappear. Former critics accused Dolabella of being “sarmatized” to the full. Whereas today, critics emphasize continuity with the Venetian schools in which he apprenticed. It is certain that the vast majority of imaginatively painted characters have strong southern features: when looking at the painting of St. Thomas Aquinas, we are struck by angels’ and apostles’ similarly straight (and prominent) noses, high cheekbones, full but firm lips. The Sarmatian palette gained new shades thanks to Dolabella. In addition to the previously existing purple, vermilion and ocher appear more and more often, the robes of angels flutter in shades of a slightly muted, powdery pink.

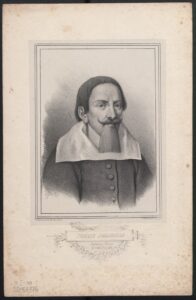

A special achievement is the imaginary “School of Saint Thomas Aquinas”, in which, among the students of Aquinas, three rulers were depicted: Sigismund III Vasa, Władysław IV Vasa and John II Casimir Vasa. Beside them and some other members of the ruling family, from the side, from a distance of full respect, but with awareness of his own worth – a dark, Spanish-dressed man with strong features, thick chin and piercing eyes looks at us. Dolabella? He looks better than his most famous portrait (though only the mid-19th century copy exists, the original burned down). One can see that it was he who dictated conditions to monasteries and monarchs at that time. At least when it comes to light and price.

But those visitors who care less about the art of painting and more about experiencing the richness of the baroque imaginarium will not be disappointed either. Galleys and rafts float on Dolabella’s canvases, Jews travel along the road, Tatars trot on the meadows, nobility menacingly erect or proudly stroke their sabers, the ancient Virtues show many of their charms. In the painting depicting the temptations (and triumphs) of St. Dominic the devil in the form of a dragon is green, lizard-like and fanciful, almost like on the famous canvas of St. George by Ucello, and on the scenes from the bishop’s palace showing the fourth element, i.e. Air, guinea fowl, eagle owls, grouse and peacocks proudly show their feathers on the wind.

One of the favorite Baroque effects was the “casket design”: placing the work in an unexpected context, “looping” the story as if in the fairy tales of A Thousand and One Nights. The Dolabella exhibition at the Royal Castle in Warsaw also refers, somewhat casually, to this effect. When Sigmundus III Vasa moved the capital from Krakow to Warsaw at the end of the 16th and at the beginning of the 17th centuries, the Venetian painter kept his studio in the former city. It is known, however, that he was at the royal court in Warsaw, his canvases were probably present, and certainly discussed, also at the Castle.

The Warsaw seat of the Vasas and successive elected kings had since then experienced the difficult fate of 19th-century and modern Poland. Desolate after the Third Partition by the Prussians, it turned into the residence of tsarist governors in the 19th century, restored in the Second Polish Republic, it was bombed by the Germans in September 1939 and destroyed by them six years later, after the pacification of the Warsaw Uprising. After being rebuilt in the 1970s, the Royal Castle became one of the most important museum and exhibition spaces in Poland. It is hard to imagine a better interior to show the times, achievements and workshop of the greatest painter at the Vasa court.

Dolabella. Venetian painter of the Vasa. Exhibition at the Royal Castle in Warsaw, 11 September – 6 December 2020. Concept and script of the exhibition: Jerzy Żmudziński, arrangement: Żaneta Govenlock; curator: Dr. Magdalena Białonowska

Author: Wojciech Stanisławski

Transation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin