During World War II, 1,780 Polish clergymen were detained in KL Dachau, and 868 died there. “They forced me to live in ‘splendid’ barracks for thousands of people, to sleep on wooden, hard bunks under one blanket. They gave me the honor of being a guinea pig,” recalled Tadeusz Jasiński, one of the survivors.

by Jan Hlebowicz

On March 22, 1933, under the orders of Heinrich Himmler, the first German concentration camp was established in Dachau, Bavaria. The area was chosen deliberately for its unsanitary and damp environment. KL Dachau became a “model camp” and a training ground for personnel who would later oversee the concentration camps being built in Germany and Europe. This camp’s first commandant, SS-Oberführer Theodor Eicke, developed a training system for SS men that fostered hatred and contempt for the “enemy behind the barbed wire.”

Initially, the prisoners of KL Dachau consisted primarily of Germans who were considered opponents of the NSDAP, including communists, socialists, and individuals deemed “asocial,” such as pimps, prostitutes, and thieves. They were quickly joined by the first clergymen of various churches and Jews after the introduction of the Nuremberg Laws. From 1940, prisoners from all conquered countries were sent systematically to the camp. It is difficult to determine the exact number of prisoners, but it is usually estimated that about 250,000 people (including approximately 28,000 Poles) were in KL Dachau.

Dachau, the German concentration camp, became the main center for the extermination of the clergy, a total of 2,720 priests would be imprisoned there. Among them were 2,579 Roman Catholic priests, most of whom were of Polish origin. During the Holy Mass celebrated in the former camp on April 30, 1995, Cardinal Friedrich Wetter, the Archbishop of Munich, emphasized: “Although we do not see any graves here, we are in the world’s largest priests’ cemetery. Poles suffered the greatest sacrifice […]. The reality was worse than our idea of what happened here then.”

Wounds that will not heal due to hunger

In April and May 1940, the first major transports of Polish priests, who had previously been imprisoned in various German concentration camps, were sent to Dachau. These transports would continue until the end of the year. The decision to transfer the priests was made by Himmler, as a result of the efforts of Archbishop Cesare Orsenigo, Apostolic Nuncio in Berlin, and Heinrich Wienken, special commissioner of the Fuldan Conference, who put forward a proposal to gather imprisoned Catholic priests “in one light-security camp.” The priest-prisoners accepted this decision with joy. “Suddenly and unexpectedly came the news about the transfer of priests from Buchenwald to Dachau, hope for an improvement in living conditions began to rise in our hearts, although in the long run, it turned out to be illusory,” recalled one of them. After checking whether all were present, the priests were taken to a large room, and their personal details recorded. Then everyone received their camp number.

In the next room, the clergy had to strip naked and surrender all their belongings, including personal possessions and religious objects, such as medals, rosaries, breviaries, and prayer books. “I experienced this moment very hard. Only braces and handkerchiefs were left,” remembered Leon Stepniak. Later, their heads were shaved (“we were severely injured in the process”), and they were forced to bathe. After that, the priests received canvas shoes with wooden soles and “striped rags” that were usually “too short and too tight.” Stepniak reported, “The red triangle [intended for political prisoners, including Poles] with the letter ‘P’ written on it and the camp number had to be sewn to the striped shirt in the designated place.”

Das im März 1933 von der Hitlerfaschistischen Diktatur für politische Gegener eingerichtete Kozentrationslager Dachau.

Zum Weihnachtsfest 1933 werden aus den verschiedenen Lagern etwa 6000 Häftlinge im Rahmen einer Gnadenaktion entlassen.

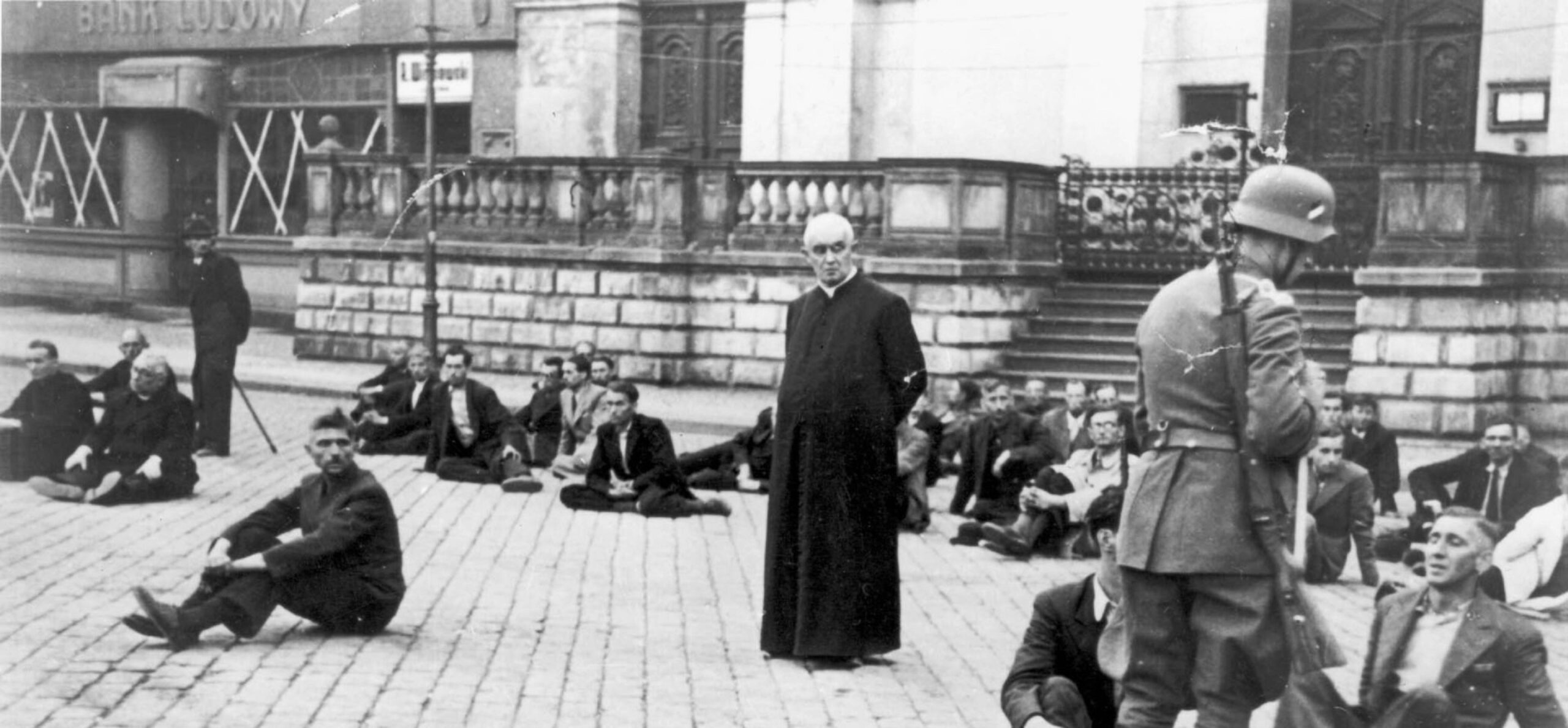

The camp commander gives a speech to prisoners about to be released as part of a pardoning action near Christmas 1933 (photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R96361 / CC-BY-SA)

Newly arrived prisoners were subjected to a six-week quarantine, during which they were forced to perform a series of “exercises.” One of them was making beds “to the edge.” Marta Małgorzata Gorajczyk explained, “It was a particularly strenuous activity for older priests. The bed must have looked like a box, smoothed out at right angles. This look was obtained after making edges on the mattress with a special plank, covering it with a blanket in a specific way, and arranging the pillows.”

Those unable to do the “edge” quickly enough were subjected to severe beatings and forced to start the work again, depriving them of the opportunity to eat. Breakfast consisted of black, unsweetened coffee and a piece of bread, which was distributed around the clock. Lunch usually consisted of turnip or cabbage soup, while dinner consisted of either soup, peeled potatoes, or a piece of bread with margarine, sometimes with marmalade. These rations amounted to a total of 800 to 1000 calories a day. The permanently hungry prisoners ate anything they could get their hands on – grass, flowers, earthworms, frogs, hedgehogs.

According to Dr. Anna Jagodzińska, malnutrition caused the prisoners to suffer from various strange diseases. Their bodies were covered with huge, festering ulcers, and they suffered from skin diseases. “Famine lasted not one day, one month, one year, but two, three, four, and more years. Wounds from hunger do not heal. People suffered dysentery, heart, and kidney diseases, urination up to 17 times in one night, and unquenchable thirst,” recalled Mieczyslaw Januszczak.

Murder by work

The repression and mistreatment of the priests in Dachau took various forms, and one of them was hard, exhausting work. Polish clergymen were subjected to grueling labor every day from 6 to 19, with only a short break for lunch that was eaten standing up. They endured screaming, beating on the face, and kicking. Polish priests were assigned the hardest labor, such as being harnessed to plows to clear the snow from the camp streets. Those who avoided being tied to a plow had to clear snow using shovels and wheelbarrows. Stanisław Przewoźniak recalled that if “someone did not receive a wheelbarrow, they had to load snow into their jackets and thus remove it from the streets.” He emphasized that the snowfall was so heavy that their work would disappear within moments. This task was considered among the worst punishments and claimed “many lives.” “So we became ragged and wretched ghouls,” he noted. 150 Polish priests in Dachau were sent to the stone pits in Gusen. Forced to carry stones on their shoulders, the priests had to run downhill to the camp that was being built below. Many fell under the weight of the boulders and never got up again. “The exhausting work in the stone pits, hunger, and the ubiquitous filth took their toll. The plague of lice nested not only in straw mattresses but also in underwear and clothing that had not been changed for weeks […]. A six-month stay in these inhumane conditions sufficed for my priests-camp-colleagues to ask, ‘Leoś, is that you?’, remembered Stepniak. Clergy were also delegated to the so-called plantations. These were fields adjacent to the camp that were used to grow mainly medicinal plants, vegetables, and herbs. Priests harnessed to great harrows were forced to harrow the fields. As mentioned by Stępniak, this hard work “killed even young and relatively healthy Polish priests, and if someone did not die in the field, he was quickly qualified for transport to camps for those with handicaps.” It was on the plantations that most Polish priests lost their lives.

The pole and guinea pigs

The priests in KL Dachau were subjected to various punishments. One of the most dreaded was the “pole.” Initially, it was carried out on a special rack where multiple prisoners were hanged simultaneously. Later, it was moved to the bathhouse, where the convicts were hung one by one on hooks attached to the ceiling. Ambrożkiewicz described the process of the “pole”: “The executions were carried out by an attendant in the bathhouse. When it was our turn, we took off our jackets, unbuttoned our shirts, and everyone stood under the designated hook. I climbed onto the high stool he placed under my bath hook. My hands, on which I put wool socks to protect against cuts, were placed on my back with the outer side facing me. When the attendant, tying them with a chain at the wrist, pulled his hands up, I held them with all my strength to my back, so that I would have some “release” later. The attendant hooked the chain on a hook in the ceiling, and I jumped off the stool gently. Whoever lingered on the stool had it torn from under his feet. Sharp pain could be felt in the dislocated shoulder joints, which, like fire, penetrated the entire upper limbs.”

Several hundred Polish priests went through the punishment of the “pole.” After an hour of hanging, the prisoner was unable to move his hands for days or weeks, and it was not uncommon for him to lose fingers or hands to gangrene. Catholic priests were also subjected to pseudo-medical experiments. Among the “experimental rabbits” was Tadeusz Jasiński. The priest was infected with malaria bacteria, and phlegmon (a severe and painful bacterial infection of the limbs). These experiments were designed to study the progression of the disease and determine the appropriate treatment for German soldiers.

Jasiński survived the experiments, but continued to experience significant pain several decades after the war. “These bestial nature of these experiments unfortunately left a permanent mark, and often today, years later, a monstrous attack of malaria comes unexpectedly, for which no medicine has any effect.”Additionally, “The effects in the form of leg paresis are felt to this day.” In memoirs of the priests from the Congregation of the Missionaries of St. Vincent de Paul, it was recorded that few of the infected survived the phlegmon experiment. “The effect of the injection was terrible, the legs swelled, some writhed in pain, others lost consciousness. Those who couldn’t make it were killed with an injection of phenol, while those who showed a chance of survival were treated. It wasn’t easy because their bodies were covered with channels that oozed pus. Sometimes the disease was so advanced that surgery was necessary.”

A wafer in a box

Throughout most of the time that KL Dachau was in operation, Polish priests were not allowed to celebrate the Eucharist, pray, recite the breviary, or carry any religious object with them. Camp officials even forbade providing spiritual help to dying fellow prisoners. “Despite these prohibitions, the priests organized a hidden religious life. Through the outgoing kommandos working in Munich, they arranged for communicants and secretly celebrated Holy Masses in prison striped uniforms,” wrote Dr. Anna Jagodzińska. Holy communion was distributed most often in the morning, when the beds were made in the barracks. Many clergy also carried the hidden wafer to their workplaces. Adam Kozłowiecki, noted in his memoirs: “I have a tiny vaseline box, in which I get 7 consecrated particles, each measuring 7×5 mm at the most. I carry this box with me all the time, I consume it every day, and if necessary, I give it to others.” In turn, Bishop Michał Kozal, through his contacts with German priests, tried to obtain a consecrated wafer, which was carried as a viaticum (Holy Communion for the dying) for those dying in the hospital and for priests sent to death in “invalid transports.” “This task was performed by priests and seminarians, also when in 1942 an epidemic of typhoid broke out in the camp. Later, holy communion was delivered to the camp hospital in a box. It was distributed to the sick by a priest acting as a porter. Where priests could not reach, fragments of consecrated wafers were given to trusted prisoners performing the service of camp ministers. During the typhus epidemic at the end of 1944, priests, risking their lives, served their fellow prisoners as orderlies and brought them sacramental assistance,” wrote Slawomir Kęszka.

One of these priests serving those dying of typhus was the future blessed Stefan Wincenty Frelichowski. Within the block of Polish priests, he also organized common evening prayers, and initiated the creation of three secret structures among the clergy – the camp “Caritas,” the seminary and the Legion of Christ. Infected with typhus and suffering from pneumonia, he died on February 23, 1945. At a similar time, news about the evacuation of other camps arrived in Dachau. Finally, on April 29, 1945, KL Dachau was captured by a small unit of American soldiers from General Patton’s 7th Army. Jan Woś noted on May 3: “In the afternoon we went to the parade ground. Rapportführer Franz Böttger, the executioner who carried out the executions and shot clergymen a week ago, was captured. He was recognized by the prisoners from the rabbit-breeding commando, called the ‘rabbiters’ commando.’ He was standing on the turret of the Jourhaus in a häftlingo suit. He was ordered to shout ‘Heil Hitler.’ We knew that he murdered thousands of prisoners with his own hands, shooting them in the back of the head, hanging them on the gallows or burning them alive in the crematorium ovens, as he did with the American airmen. But he’s just a pawn among these criminals.”