Piłsudski was of the opinion that the Republic of Poland could not survive between “two millstones” – the Russian Empire and Germany. Germany was ethnically homogeneous; it was impossible to break them down. The shifting of the border in Silesia, Pomerania or Prussia would not change the essence of the potential disproportion between them and Poland. The ethnic border with Germany had to remain a political border. Poland was bordered to the East by Lithuania, Belarusia and Ukraine, and not with the Russians – writes Przemysław Żurawski vel Grajewski.

by Przemysław Żurawski vel Grajewski

On 11 November 1918 in Compiègne, a truce was reached between Germany and the Allied Powers that ended the First World War. The defeated Reich was obliged, among other things, to withdraw German troops in the east to the old border from 1914, which they began to do. Additionally, Ober-Ost (the German command for the Eastern Front) and the Bolsheviks concluded a secret agreement under which the areas evacuated by the Germans were transferred to the Soviets.

In December, there were clashes between the Red Army and the Polish defenders of Minsk who had retreated to the west. Then on 6 January 1919, the Soviets seized the city of Vilnius after defeating the Polish resistance. On 13 February, near Bereza Kartuska, and a day later in the south-east of Grodno near the town of Mosty on the Nemunas in Belarus, the first armed clashes between regular units of the Polish Army and the forces of the estern Front of the Red Army took place. These skirmishes are considered the beginning of the Polish-Bolshevik war.

After a year and a half of fighting, the battles ceased on 18 October 1920 and peace was concluded on 18 March 1921. There were many parties to the conflict as alliances were unstable and changed often. Overall, a wider readership has been poorly exposed to the events that unfolded around the Ukrainian issue at the time. Thus it requires a broadening of perspective to present the participants of the described events and the evolution of their political and military positions. Therefore, we will begin with the international conditions of the Ukrainian case during the Polish-Bolshevik war by going back a dozen or so years – to the point when both Poles and Ukrainians entered the 20th century.

Competitors at the starting line

The partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth divided not only the Polish but also the Ukrainian territories. The latter were torn between the Russian Empire and the Habsburg monarchy, which deepened the differences between the Transnistrian Ukraine conquered by Russia and the Ruthenian and Belz regions seized by Austria, renamed Eastern Galicia, whose core was the former Red Ruthenia. Since the Middle Ages, this territory had been more strongly oriented towards the West than other parts of today’s Ukraine. (For the sake of simplicity, let’s omit Austro-Hungarian Ruthenia and Bukovina, which did not play a significant role in this game). Under Moscow’s rule, the Eastern Church was compulsorily incorporated into the Orthodox Church. The Eastern Church survived under Austrian rule. This resulted in the religious division of Ukraine that still exists today.

The beginning of the last century found Poles and Ukrainians in a state of complete captivity. The central territories of Poland, belonging to the Russian Empire, were then called the Vistula Land, and the Russian part of Ukraine – Little Russia, [a geographical erasure] that denied both nations the right to exist. Both Poles and Ukrainians enjoyed better conditions – even after 1867 – in constitutionally-led Austro-Hungary. During the reign of Tsar Alexander II (who was considered a “liberal”), on the basis of a decree issued by the Minister of the Interior, Pyotr Valuyev, on 18 July 1863 (at the height of the January Uprising), and on the basis of the Tsar’s decree of 1876, Russia brutally removed the Ukrainian language from the public space, prohibiting all journalistic, scientific and cultural activities in this language on the territory of the Russian Empire as well as banning the importation of any publications in this language from abroad. In Ukrainian governorates, teachers were replaced, local teachers were sent deep into Russia and replaced with Russians. While the ruthless Russifier Dmitrii Bibikov and successors such as Mikhail Yuzefovich ruled in Kiev, and their counterparts Iosif Gurko and Alexander Apukhtin in Warsaw, children suffered corporal punishment for speaking Polish or Ukrainian at school. In Galician Lwów under the rule of the Habsburgs there was Polish autonomy. There was a Polish Sejm, a Polish-language administration and courts, a Polish university with Ukrainian academic departments, a Polish and Ukrainian press, Polish and Ukrainian political parties, as well as cultural, educational, economic and social organizations, and a flourishing literature and art scene. Lwów was also the seat of the Roman Catholic, Greek Catholic (Eastern) and Armenian Catholic archdioceses. Moscow’s rule in Warsaw and Kiev made Lwów the cultural and political capital of both Poles and Ukrainians. Neither had a similar center of national life of this rank elsewhere. It is necessary to realize this in order to understand the context of the Polish-Ukrainian war for Lwów and Eastern Galicia (1 November 1918 – 17 July 1919), which lasted several months in parallel with the Polish-Bolshevik and Ukrainian-Bolshevik wars.

In the years preceding the First World War, Polish and Ukrainian shooting organizations began to flourish in Galicia. At the outbreak of the war, the Ukrainians, like the Poles, created their own combat unit – the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen, and under their own slogans and banners, like the Poles, entered the war with Russia alongside Austria-Hungary (it is worth mentioning Piłsudski’s friendly attitude towards this initiative).

The war between the European powers led to the occupation of most of the Polish lands by German and Austro-Hungarian troops in 1915. Taking advantage of this fact, the Poles began building the foundations of their own state. As part of the German protection system, the Regency Council was established, the seeds of the Polish administration were sown, and even a small army began to coalesce – the Polnische Wehrmacht. The Ukrainians did the same, but only three years later, when the Russian Empire had collapsed and the armies of the central states pushed the Russians out of Transnistrian Ukraine.

The Ukrainian National Revolution

On 17 March 1917, after the tsarist regime was overthrown by the February Revolution, activists from left-wing Ukrainian parties formed the Central Ukrainian Council, seeking to take control over Ukraine without breaking ties with Russia. The Bolshevik coup in Petrograd, however, led the Central Ukrainian Council to publish the Third Universal on 20 November 1917 – the announcement of the establishment of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, which remained in a federal relationship with Russia. On 22 January 1918 – the Fourth Universal was published, which was a declaration of the full independence of the Ukrainian People’s Republic. Unfortunately, on 14 January 1918, the Red Army launched an offensive against the Central Ukrainian Council. On 28 January, a Bolshevik uprising broke out in the heavily Russified capital of Ukraine, and on 8 February Soviet troops entered Kiev. At the same time, the Ukrainian People’s Republic was introduced by the central states into the arena of international politics. On 9 February, the Central Ukrainian Council delegation signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which was then adopted by Soviet Russia on 3 March under pressure from Germany. This treaty, on the one hand, placed Ukraine under the occupation of the central powers, and on the other, forced the Bolsheviks to recognize the Ukrainian People’s Republic. It also caused the final breakdown of all cooperation of major political forces in Poland with Germany and Austria-Hungary, weakened since the fidelity crisis concerning the Polish Legions [Polish units were to swear fidelity to Germany and Austria but refused to do it, as a result of which Piłsudski was arrested and imprisoned in Magdeburg, 9–11 July 1917]. In the shade cast by these events, the rebellion of the 2nd Legion Brigade and its transfer to the other side of the front at Rarańcza (15–16 February 1918) was very symbolic. What decided it was the transfer of the Chełm Land to the Ukraine’s People Republic. Thus, Transnistrian Ukraine found itself in a sharp conflict with “non-existent” Poland and appeared to the West as a protégé of Germany. Just at that moment Poland, having taken advantage of possible development in cooperation with Berlin and Vienna, severed ties with them and moved to the camp of the future victors – the Western powers.

Between 27 February and 22 March 1918, the Army of the Ukraine’s People Republic, supported by Germany and Austria-Hungary, liberated large areas of Ukraine from Kharkiv and Poltava to the Crimea. However, the protection of the Central Powers was not for free. On 1 March 1918, German troops entered Kiev. The Central Ukrainian Council, which opposed their exploitative policy, was dissolved on 28 April by the Germans, and a day later, with their support, General Pavlo Skoropadsky became the hetman of Ukraine. He was a representative of the “Little Russian” elite. This gentry of left-bank Ukraine, were Russified but with some local awareness, were often descendants of famous old Cossack families, such as Skoropadsky himself. In view of the illiteracy and Russification of cities common among peasants, this was the only social class capable of building a state administration in Transnistrian Ukraine. Unfortunately, poor awareness of a common national identity and class egoism made it impossible to gain the support of the population. Skoropadsky was not recognized by the Ukrainians fighting for independence and his power did not last longer than the German occupation.

The defeat of the Central Powers on the Western Front in November 1918 radically changed the situation both in Transnistrian Ukraine and in Eastern Galicia. On 16 October 1918, Emperor Charles I issued a manifesto announcing the transformation of Austria-Hungary into a federation of autonomous nation states. On this basis, two days later, leading Ukrainian politicians from Galicia established the Ukrainian National Council in Lwów and proclaimed the creation of the Ukrainian state within Austria-Hungary, composed of Eastern Galicia, Subcarpathian Ruthenia and Northern Bukovina. With the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy, using the forces of Ukrainian paramilitary organizations and those divisions of the Austrian army dominated by Ukrainian soldiers, on 1 November, the Council attempted to seize power in Lwów. It led to an armed uprising of Poles who were a majority in the city, economically and culturally, and to the outbreak of Polish-Ukrainian fights. Established at the beginning of November 1918, the Ukrainian state in Eastern Galicia, which adopted the name of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic, found itself at war with the resurgent Poland. From that moment on, there were two Ukrainian states: the Ukrainian People’s Republic in the former Russian Ukraine and the West Ukrainian People’s Republic in Eastern Galicia in the former lands of the Habsburg monarchy.

By that time, the occupation of the central powers in Transnistrian Ukraine had collapsed. On 14 November (i.e., after Germany reached a truce in the West), Skoropadsky announced the act of federation of Ukraine with white Russia. This made the former Central Ukrainian Council politicians, led by Volodymyr Vynnychenko, to form the Ukraine People’s Republic Directorate (15 November) and to an armed uprising of Sich Riflemen against Skoropadsky. This began in Biała Cerkiew on 16 November. Ataman [commander-in-chief] Symon Petlyura stood at the head of the Directorate troops. Skoropadsky resigned on 14 December, and on 20 December, the Directorate forces entered Kiev. Meanwhile, on 22 November, the troops of the West Ukraine People’s Republic were forced out of Lwów by Poles. Stanisławów became the seat of the West Ukraine People’s Republic authorities. There, on 4 January 1919, the treaty on the federation of the Ukraine People’s Republic and the West Ukraine People’s Republic was signed. The latter formally became the Western Ukraine People’s Republic District. The solemn proclamation of the unification of the two Ukrainian states took place on 22 January 1919 in Kiev at St. Sophia square. This was not peace yet, however. In the South, in Yekaterinoslav, Ukrainian forces fought against the anarchic army of Nestor Makhna. While in the northeast, in January, the Bolsheviks broke the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and took Kharkiv. As a result, the Ukraine People’s Republic Directory on 18 January declared war on Soviet Russia. In the fierce 16-day battle of Poltava, the Ukrainians were initially successful, but as a result of Bolshevik propaganda, some units of the Ukraine People’s Republic Army broke up, which led to it leaving Kiev, occupied without a fight by the Red Army on 14 February, and the loss of the entire left-bank Ukraine. The attempt of the Ukrainian anti-Bolshevik counteroffensive at Berdychiv and Kozyatyn in March 1919 failed, despite the passive attitude of the Polish Army in Volhynia, which at that time did not conduct any major operations against the forces of the Ukraine People’s Republic. The Ukraine People’s Republic Directorate moved to Vinnytsia, then to Równe, and then to Kamieniec Podolski. Further progress of the Soviets was stopped by the attack of the White troops of General Anton Denikin, which beat them in Donbas. However, the Whites considered Ukrainian fighters for independence a new incarnation of the “mazepins” – in Russian imperial phraseology synonymous with the betrayal of “Little Russian people breaking out of the unified trunk of the Russian nation” – so they also attacked the Ukraine People’s Republic. The united Ukrainian states were therefore at war with both White and Red Russia, as well as with Poland and Romania, whose army entered Bukovina and Pokuttya in November 1918. In this situation, the Ukraine People’s Republic attempted to obtain the support of the Western powers and their intervention forces which landed in Odessa and Crimea. The West, however, supported White Russia which did not recognize the aspirations of Little Russia and reluctantly agreed to the separateness of the “Vistula governorates”, while claiming it for Eastern Galicia.

A Ukrainian buffer

As indicated above, at the time of the outbreak of the Polish-Bolshevik war, Ukraine was already in conflict with Soviet Russia, but in reality only the Ukraine People’s Republic was fighting against the Soviets, whose troops also fought against Poles in Volhynia. On the other hand, the West Ukraine People’s Republic, despite its formal unification with the Ukraine People’s Republic, retained a separate army (Ukrainian Galician Army) and a government headed by Yevhen Petrushevych, which was at war with Poland, but not fighting at that time against the Bolsheviks. Until mid-1919, the Ukrainian armies separated Poland in a theater of war operations stretching south of the Polesye marshes from both Bolshevik and White Russian forces. Thus, in its first stage, the Polish-Soviet war was fought only north of Pripyat, i.e. in the territory of Belarus, in the Vilnius region and in Latvian Latgale, which, together with its capital – Daugavpils (Daugavpils) – liberated the Polish Army together with the Latvian Army in January 1920. The Ukraine People’s Republic also separated Poland from the White Volunteer Army, which allowed Poles to avoid a politically high-risk military clash with supporters of “one and undivided Russia” such as Denikin. Ukraine could not avoid this confrontation, which had a devastating effect on its relations with the Triple Entente.

A bad start – Ukraine and the stigma of being Germany’s protégé

In February 1919, when the Polish-Soviet war began, Allied intelligence managed to intercept the text of the undated military convention concluded after 31 January 1919 between the Ukrainian forces fighting against Poles (not only in Galicia), and the command of the German XXI Corps, which was part of troops of the Ober-Ost region retreating from the East. The principles of German-Ukrainian cooperation against Poland were clearly defined in it. When the case was discussed by the Supreme Military Council of the Allied and Associated Powers, Germany was accused of violating the terms of the 11 November 1918 ceasefire. In the new situation, as Roman Dmowski described it to representatives of the great powers a few days before this event, showing Poland – an ally of the Triple Entente – as a state threatened on three sides by the Bolsheviks, Germans and Ukrainians, gained a new significance. The presence of Ukrainians in that company could only be to their disadvantage in the eyes of the participants of the peace conference in Paris. The contacts between Halych (Galician Ukrainians) and Hungary were an additional political burden of the Ukrainian case for the Allies. The West Ukraine People’s Republic government tried to buy weapons in Hungary in exchange for crude oil from Galician wells it controlled. The talks undertaken during Mihály Károly’s rule were not concluded, but the offer was made by the Hungarian Soviet Republic of Béla Kun. Contact with the Hungarian communists was an even more serious sin in the eyes of the Triple Entente than the negotiations with the previous government.

Dramatic turns on the Ukrainian fronts

In the first half of 1919, the Ukraine People’s Republic concentrated its military efforts on anti-Russian fronts, fighting both the Reds and the Whites. In fact, they were not able to join the war with Poland in Volhynia, so there were no intensive Polish-Ukrainian fights there. The West Ukraine People’s Republic did the opposite, focusing on the confrontation with Poland and negotiating with the Bolsheviks. They already lacked the army for an armed confrontation with the occupying Pokuttya and allied with Poland and the Triple Entente Romanians. In April, Poland launched an anti-Bolshevik offensive in Lithuania and Belarus, liberating Baranovichi, Pinsk, Vilnius, Navahrudak and Luninets, and then Minsk, Bobruisk and Barysaw, basing the front on Berezin. In November 1919, the Polish Army reached its farthest range, displacing the Soviet forces from Lepel, Kamien and Ushachy, and in the following months operated on the lake line east of the latter, south of Polotsk and west of Vitebsk. They then stopped at the behest of Józef Piłsudski, as further pressure on the Bolsheviks might have facilitated the offensive by Denikin, whose White Volunteer Army enjoyed triumphs until November 1919, advancing on Oryol, Tula and Moscow. It was the right decision. Beating the Bolsheviks and Denikin was possible, but it would lead to a clash with the Whites. Fearing a German revenge, France dreamed of renewing its alliance with Russia. The Bolsheviks who were in a dialogue with Germany, and striving for a world revolution on the condition of turning Germany to Communism and breaking the peace treaty established in Paris, were completely unfit for this. Soviet Russia was an enemy not only of Poland but also of France, being essentially an ally of Germany. White Russia was the enemy of the Bolsheviks and the Germans – a longed for ally of Paris, invariably remaining the enemy of Poland’s independence. Piłsudski believed that the colour of the Soviet empire was of secondary importance, and that Poland would have to fight against Russia for its independence anyway. He made sure that Poland became an ally of the West when it came to fighting the enemy – the Bolsheviks. He did not want Poland to be the main hindrance to the Franco-Russian alliance, and therefore an enemy of the West with its ally (White Russia). By refusing to support Denikin, he saved the Bolsheviks, kept Poland in the camp of the victors of the First World War, and excluded Russia from it. The Ukraine People’s Republic failed, and the Triple Entente’s nascent support for Kiev ended abruptly with the outbreak of the Ukraine People’s Republic Army’s fighting against the Denikinists. Pressed from the south-east by the Whites and from the north-east by the Red Russians, the soldiers of the Ukraine People’s Republic retreated towards Polish lines.

Increasingly serious differences emerged between the previously cooperating Ukraine People’s Republic and West Ukraine People’s Republic. In May 1919, Polish intelligence officer Lieutenant Jan Mazurkiewicz, went to Petlyura with the task of checking whether it was possible for the Supreme Ataman of the Army to send his representative to Warsaw. The mission was successful. The Ukrainians in Transnistria, under pressure from the Red Army, sought an agreement with Poland. Unfortunately, the Galician Ukrainians did exactly the opposite – they sought a ceasefire with the Bolsheviks in order to be able to focus their forces against the Polish Army. When the Red Army reached Zbrucz on 7 May 1919, the Soviet authorities turned to the West Ukraine People’s Republic government with a proposal to set a demarcation line and conclude a ceasefire. This proposal was, after some hesitation, accepted on 31 May 1919 by the commander-in-chief of the Galician Ukrainian Army, General Mykhaila Omelianovych-Pavlenko, who was admittedly disavowed by the West Ukraine People’s Republic government and paid for his decision with the loss of his position, but this step did not go unnoticed in Paris. The fear of the revolution was quite real.

The commanding officer of the Ukrainian Front of the Red Army, General Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko, was ordered to contact the Hungarian Soviet Republic through Galicia and Bukovina. It was prevented by the rebellion of the 6th Ukrainian division, which served in the Red Army at that time, and was commanded by the former ataman Nikifor Grigoriev, but the possibility of a Soviet attack was not averted. The Ukrainians’ seemed too weak to form an anti-Bolshevik barrier and the impression was not obliterated by the most brilliant Galician Ukrainian Army operation in the war against Poland, known as the Chortk offensive (8–27 June 1919), which threw the Polish troops approaching Zbrucz back to the Hnyla Lypa line. However, it exposed the southern wing of the Petluryans in Volhynia, exposing them to a Bolshevik attack in a situation when the attack of the Polish Army on Lutsk tied the northern group of the Ukraine People’s Republic troops, which was exploited by the Bolsheviks who struck from the South-East and capturing Równe, Shepetivka, Ploskirov and Kamieniec Podolski. The success of the Ukraine People’s Republic on the battlefield with Poland, separating Soviet Russia from the revolutionary centers in Hungary and Germany, and the collapse of the Ukraine People’s Republic under the pressure of the Bolsheviks, was the exact opposite of what Paris was expecting from the Ukrainians. Under these conditions, on 24 May, the Ukraine People’s Republic reached a truce with Poland and, having reorganized the army, seized Podolia and Kamieniec from the Bolshevik hands.

The inhabitants of Galician Ukraine at that time were at war with Poland and were losing. Until 17 July 1919, when the Poles ousted Galician Ukraine for Zbrucz, thus liquidating the West Ukraine People’s Republic. After crossing Zbrucz, Galician Ukraine together with the units of the Ukraine People’s Republic (about 85,000 and 15,000 partisans in total) carried out a victorious offensive against the Bolsheviks and entered Kiev on 30 August. Unfortunately, on the next day the Ukrainian army was forced out of the capital by Denikin’s white army. Pressed by the White and Red Russians, the Ukrainians began to retreat. In this dramatic situation, between the Russian factions and Poland, there was a split among the Ukrainians themselves. The Ukraine People’s Republic, seeing Russia as its main enemy, began to lean towards an alliance with Poland. The price of this alliance, however, could only be the relinquishment of Eastern Galicia by Ukraine, which was unacceptable to the combined Ukrainian forces, which were the Galician Ukraine troops originating from the West Ukraine People’s Republic, which considered Poland its main enemy. In August 1919, the Ukraine People’s Republic diplomatic mission of Pylyp Pylypchuk arrived in Warsaw. On 1 September, a ceasefire was reached between Poland and the Ukraine People’s Republic and discussions began on Polish material aid for Petlyura’s troops. In September 1919, the Ukraine People’s Republic Minister of Foreign Affairs Andriy Livitskyj came to Warsaw to negotiate an initially secret alliance with Poland, which was finally concluded in February 1920. Before this happened, the Galician Ukrainians severed their relationship with the Ukraine People’s Republic and on 17 November 1919, they went over to Denikin’s side (Galician Ukraine became the Galician Ukraine Army), and after his defeat – to the Bolshevik side (transforming on 12 February 1920 into the Red Ukrainian Galician Army). In November 1919, the Polish Army crossed Zbrucz and occupied Kamieniec Podolski, thus creating a territorial base for the authorities of the Ukraine People’s Republic, which first took refuge there from Denikin’s Volunteer Army, and then from the Bolsheviks. Petlyura arrived there on 5 December. The remaining units of the Ukraine People’s Republic, grouped in the “death triangle” of Chortoryja-Lubar-Miropol, by the decision of the command made at the meeting in Chortorya on 4 December 1919, began partisan operations in the rear of the Bolsheviks and the Whites (the so-called first winter march of the Army of the Ukraine People’s Republic between 6 December 1919 and 6 May 1920).

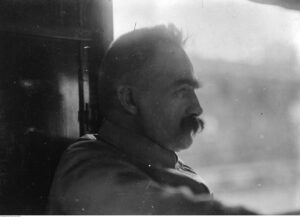

Piłsudski was of the opinion that the Republic of Poland could not survive between “two millstones” – the Russian Empire and Germany. Germany was ethnically homogeneous; it was impossible to break them down. The shifting of the border in Silesia, Pomerania or Prussia would not change the essence of the potential disproportion between them and Poland. The ethnic border with Germany had to remain a political border. Poland was bordered to the East by Lithuania, Belarusia and Ukraine, and not with the Russians. “Unraveling the national stitches of the Russian Empire” would change the balance of power in favour of Poland. The success of this project depended on the independence of the largest non-Russian nation in this area – the Ukrainians. This calculation was the basis of the Polish-Ukrainian military alliance at the decisive stage of the Polish-Bolshevik war. On 21 April 1920, the government of the Republic of Poland and the Ukraine People’s Republic Directorate signed an inter-state agreement in which Ukraine gave up Eastern Galicia, while Poland officially recognized the Ukraine People’s Republic, promising its support in the war for independence. The appropriate military arrangement was concluded three days later. The result of these agreements was a joint offensive by Polish forces and the Ukraine People’s Republic units on Kiev, which was seized on 7 May. Some of the former Galician Ukrainian Army troops that were part of the Red Army opened the front to the allied Polish and Ukrainian troops.

The further fate of the Ukraine People’s Republic was decided by the vicissitudes of the Polish-Soviet war. On 9 June, Polish troops left the capital of Ukraine. Ukrainian troops bravely fought during the Polish retreat in the summer of 1920. Colonel Marko Bezruchko’s 6th Division’s persistent defense saved Zamosc, and the troops of General Omelianovych‑Pavlenko cooperated with the Polish 6th Army, maintaining the Dniester line in defense of Eastern Galicia against Budyonny’s Cavalry Army. After defeating the Bolsheviks near Warsaw and on the Nemunas, the Ukrainians did not recognize the ceasefire of 18 October 1920, so their divisions of 23,000 soldiers continued fighting until 20 November. The remains of these units, pushed out by the Russians, were interned by the Poles, among others, in Szczypiorno, where Polish legionnaires were once kept.

By the Treaty of Riga on 18 March 1921, Poland withdrew recognition of the Ukraine People’s Republic and recognized the Ukrainian Soviet Republic dominated by the Russians, distrustful even of Ukrainian Communists, and led by the Bulgarian Christian Rakovsky. The Ukrainian version of the document was edited by Leon Wasilewski – a member of the Polish delegation, as the delegation of the Soviet Ukraine was unable to draft an official text in the language of the country it allegedly represented.

The last chord of the fight for the independence of the Ukraine People’s Republic was the second winter march of its troops (4 November – 6 December 1921), which ended with the pogrom of their largest group at the village Małe Mińki in Zhytomyr Oblast (17 November) and the execution of 359 prisoners taken there by the Bolsheviks and carried out in Bazar on 23 November.

The weakness of the sense of national unity in Ukraine, and the maximization of goals of the West Ukraine People’s Republic leaders in Galicia, determined the defeat of Ukraine in the war for independence. The Ukraine People’s Republic was unable to defeat Red and White Russia on its own. On the other hand, the West Ukraine People’s Republic, reaching for a Lwów dominated by Poles, where Ukrainians constituted 10-19% of the population, decided to go to war with Poland, which was not necessary and unwinnable. The idea of capturing Lwów was unrealistic, as was the hope of defeating Poland with the forces of the Galician Ukrainian people themselves. However, the West Ukraine People’s Republic rejected the possibility of an agreement and division of Galicia, which existed until mid-March 1919, along the line proposed by the Allied missions, leaving Lwów and the oil deposits on the Polish side, but with Stanisławów and Tarnopol on the Ukrainian side. It was understandable, but it was a politically fatal decision. As a result, when in 1919 the fate of Ukraine was at stake in the war with the Bolsheviks, the strongest Ukrainian army (Galician Ukrainian Army) fought against the Polish Army, which from February 1919 on the Belarusian front fought against the common enemy of Poland and Ukraine. Ukraine was unable to make up for the losses it suffered at that time due to the German protection of 1918, the conflict between the Ukraine People’s Republic and the White Russia, and the West Ukraine People’s Republic with Poland which resulted in the loss of support from the West for the Ukrainians. In this situation, Poland was their only real ally. The recognition of this fact by the Ukraine People’s Republic in the second half of 1919 led to a split with the West Ukraine People’s Republic. The presence of Poles on the Dnieper was too short and the mobilization of the Ukraine People’s Republic was too low which resulted in the defeat of the Kiev expedition. Poland won the war with the Bolsheviks militarily and thus remained independent, but it did not achieve the political goal, which was a condition for its durability – it did not break up the Russian /Soviet empire by creating an independent Ukraine allied with Poland.

Author: Przemysław Żurawski vel Grajewski – Polish political scientist, professor of Łódź University.

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin

Bibliography: