The popular image of the ‘liberation of Western Belarus by the Red Army in September 1939’ was almost completely shaped by Soviet propaganda. Its core element was the image of the unreservedly grateful Belarusian peasants who, owing to the tanks crossing the border, experienced a triple liberation: social, political, and economic. The reality, however, was much more complex.

by Wojciech Śleszyński

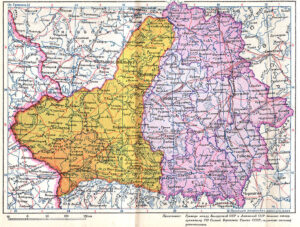

When discussing political events and the ‘discourse of violence’ in the north-eastern territories of the Second Polish Republic in the autumn of 1939, one must distinguish between the period of up to September 17, 1939 (when it was relatively safely), and the period beginning with the entry of Soviet troops into the borders of the Republic. On the same day anti-Polish sabotage groups also became active. Between September 17–25 1939, battles took place in dozens of localities between partisan formations organised by Belarusian and Jewish communists on one side, and army units, police, and Polish volunteers on the opposite. The majority of such incidents took place in the Grodno region. The most propaganda-publicised battles occurred in Skidzyel, where two-days fights took place between Belarusian and Jewish (communism–inspired) youth and a Polish punitive expedition sent from Grodno, consisting of soldiers, policemen, and scouts. Later Soviet historiography would refer to these events as the Skidzyel uprising. Polish-Belarusian clashes also occurred in the vicinity of Lida, following the entry of the Red Army.

Estates and churches are burning

As soon as the Soviet aggression against Poland began, a wave of assaults, murders, and looting began in parallel to these diversionary activities, their victims chiefly representatives of the local political and social elite: teachers, civil servants, and landowners. The scale of such crimes committed in Belarusian territories (and especially in Polesie) turned out to be surprisingly extensive, especially when compared with the Ukrainian areas. According to the findings of Krzysztof Jasiewicz, when it comes to the losses of the Polish landed gentry in September 1939, three times as many representatives of this social group died on Belarusian than Ukrainian territories (62 and 23, respectively).

Another thing is that it is difficult to distinguish clearly between political and plundering factors in the case of the attacks. Each change of power gave the local rural population an opportunity to improve their financial standing. In the period of anomie and disintegration of the government system, it was difficult not to succumb to the temptation of visiting the nearby manor for the ‘golden fleece’.

It should be stressed, that anti-Polish manifestations (in the first days of the occupation, mainly ‘of the class character’, i.e. connected with the direct revindication of property and acts of violence, real or symbolic), were in line with the concept of the ‘revolutionary nature of changes’ pushed by Moscow. The Soviet authorities were very indulgent towards various abuses by the people’s militia, treating them like a natural reaction following the long Polish period of ‘oppression and exploitation’. Rape and violence were, after all, inherent in every revolution, which was only followed by a period of happy dictatorship of the proletariat.

Land for the people

One of the methods of compensating for the historical injustice was to endow the poor rural population with manorial land. Following the directives of the Central Committee, the local Red Army commanders or the Communist Party members often deliberately stirred up class and nationality conflicts, encouraging the local population to pursue justice on its own.

In spite of this, the vast majority of Belarusian society accepted the Red Army’s entry with indifference, and only small groups of people (mainly politically conscious local elites) looked with hope at possible changes. Meanwhile, the main goal of the organised rallies was to confirm the premise that the military action taken on September 17 was only an expression of the will of the inhabitants of Western Belarus, who wanted to unite with the rest of the Soviet territories, and that the changes occurring after that date were not forced by the occupant, but were a natural reaction of the happy people excitedly awaiting the arrival of the ‘liberators’. The attitude of local communities had to harmonise with the propaganda premise that one of the main reasons for the military defeat of the Second Polish Republic was the enslavement of the working class and national minorities. The enthusiasm of the ‘working people’ was to be, in the opinion of the Soviet authorities, the first kind of plebiscite proving the righteousness of the Red Army’s actions.

This past of the Second Polish Republic was one of the basic determinants of the policy of Soviet authorities towards Belarusians. Also, the reception of this policy by the Belarusian community was conditioned by its objective economic, social, civilisational, and cultural situation before 1939, and the policy of the Polish authorities. Only against this background can we understand most of the nuances of the attitudes of the Belarusian communities towards the Soviet authorities in 1939–1941.

The slogans proclaimed by the encroaching Soviet troops, promising class and national equality, and the creation of new opportunities in access to education and government offices, sounded encouraging when confronted with the reality of the Second Polish Republic. Aversion towards pre-war government policy was further compounded by the experience of Poland’s recent military defeats, which, contrary to pompous proclamations, easily succumbed to the armies of its neighbours. The occupying authorities skilfully exploited the prevailing mood, offering visions of an easy political and professional career to the Belarusian rural poor. The Belarusian peasant hoped, above all, for a solution to the problem of ‘land hunger’.

Folklore yes, national culture no

However, not all members of the Belarusian community were enthusiastic about the announced changes. Most Belarusian peasants were reserved about the plans of the new authorities, fearing too much radicalism. However, their conservative and apprehensive attitude was not exposed for propaganda purposes.

The first months of the occupation were supposed to prove the sceptics’ fears were right. It soon turned out that the use of Belarusian slogans in the first months of the occupation was only meant to win over Belarusians at the moment of seizing power. This period ended at the beginning of 1940. The change in economic policy and the strengthening of the Soviet system coincided with changes in ethnic policy.

It is worth remembering that the attempt to gain current propaganda benefits by winning over the nationally-oriented Belarusian intelligentsia did not mean a fundamental change in the Soviet policy. Already at the end of September 1939, on the basis of previously prepared lists, arrests were made among nationally conscious Belarusians.

According to the policy of the occupation authorities, Belarusian-ness was to be reduced to the level of regional folklore, just like in the eastern regions of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. Numerous amateur folk groups and village interest circles were to serve this purpose. The educational policy was also adjusted to the above rules. The number of elementary and incomplete secondary schools was increased, but even at the level of full secondary education, the Belarusian language was supplanted by Russian. In the school year of 1939 –1940, in the Bialystok region, there were five Belarusian secondary schools and nine Russian ones, while the following year (1940–1941), the ratio was much more unfavourable for Belarusian schools – three, and Russian – 25. The Russian language also dominated the training of future teachers at the Pedagogical Institute in Bialystok.

Following the first period of relatively strong emphasis on the Belarusian character of the changes taking place, from early 1940, these slogans, contradictory to the general line of the occupant’s national policy aimed at creating a unified Soviet nation, were gradually withdrawn. The general character of the conducted Sovietisation can be traced at least using the example of cadres, which were sent to the occupied areas. Dominating among them was a Sovietised group of party officials, often better speaking Russian than Belarusian.

Freedom for kolkhozes

There were also marked changes in economic policy. The period of relative freedom (no taxes, free logging) was short-lived: already at the end of 1939 the Soviet authorities began to introduce their order and new tax burdens. Shops quickly emptied. One could not buy anything with the money had. Previously unknown queues appeared. The poor efficiency of the Soviet system, combined with the increasingly forcible introduction of the Soviet agricultural economic model, made the Belarusians less and less enthusiastic about the changes.

Another blow that fell on the Belarusian community at the beginning of 1940, was the creation of kolkhozes. Theoretically, they were voluntary, but in reality, they were founded under the strong pressure of the Soviet authorities. Interestingly, as research shows, far more kolkhozes were set up in Belarusian villages than in Polish ones.

The fear of kolkhozes coincided with the fight against kulaks, which was getting stronger in the late 1940. Anyone who owned over a dozen hectares of land could become a kulak. A large proportion of peasants was potentially eligible for this group. Although collectivisation was not as massive as in the Soviet territories in the early 1930s , by June 1941, 1,115 kolkhozes had been set up in Western Belarus. They were generally joined by poor people, who did not want to or could not farm independently.

Exile in the desert

Under the Soviet system, all rebellious people were to be eliminated. The blade of repression was therefore directed not only at those who had taken specific action against Soviet power, but also those who were merely suspected of doing it. One of the simplest ways of getting rid of the ‘enemies of the people’ from the Borderlands, was to deport them as far away as possible. They were used as slave labour, thus continuing a policy that had been followed in the Soviet Union since the early 1920s.

Between 1940 and 1941, four large deportations were carried out, sending hundreds of thousands (at least 330,000) to Siberia, Kazakhstan, and the northern regions of Russia. Entire families were deported, regardless of gender, age, or health status of their members. Apart from Poles, Jews and Belarusians were also deported. Many people, especially children, did not survive the murderous conditions of transport in freight cars. Their corpses were dumped in random places. The four great deportations were part of a wider Soviet policy of repression which affected over a million Polish citizens, including those of Belarusian nationality. After the ‘amnesty’ of 1941, a large group of them managed to join the Anders Army, and follow the entire combat trail of his Polish 2nd Corps in Italy.

Despite official Soviet propaganda, in reality the majority of the Belarusian community did not evaluate the Soviet occupation of 1939–1941 in the best light. However, the experience of war, and the actions of the Nazis, significantly changed this way of seeing matters. After the Red Army re-entered the Belarusian territories in 1944, Belarusians were left with no choice, and the majority of the community accepted the model of state and social advancement offered to them by the communist system. It also adopted the presented description of the history of 1939–1941, although it did not coincide with the one recorded in the collective memory.

Author: Prof. Wojciech Śleszyński – the Director of the Sybir Memorial Museum, and the Head of the Department of Eastern Studies at the University of Białystok

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki