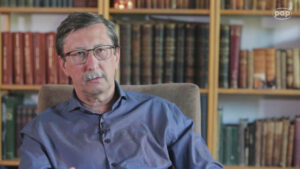

The Roman Catholic Church in Poland was perceived by occupiers, and especially the Germans, as a synonym of Polishness, says Prof. Jan Żaryn, a historian from the Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw.

Polish Press Agency: What was the situation of Christian churches in Poland during the Second World War?

Prof. Jan Żaryn: Most of the repression by the occupiers affected the Roman Catholic Church. This is due to the fact that the vast majority of Poles living in the Second Polish Republic were Roman Catholics. However, all religious communities were affected under both German and Soviet occupation. Due to the decidedly anti-Polish nature of the occupation of the Germans and the Soviets, the first and by far the most important entity to be destroyed was the Roman Catholic Church.

Why did this happen?

The Roman Catholic Church in Poland was perceived, especially by the German occupiers, as a synonym of Polishness. It was also, therefore, the main source of resistance. This German conviction dates back to the 19th century when attempts to Germanise the lands under Prussian rule were resisted, mainly by defending the Polish identity and the faith. Catholicism was a culturally distinguishing mark. Also specific churches were defended as Polish tradition could develop there contrary to the Prussian invaders. As early as in the fall of 1939, Germany launched an attack against the Roman Catholic Church in a more technological manner than in the 19th century, and in conjunction with the idea of pursuing a policy of genocide.

Did the Germans repress the Church in a similar way in the territories incorporated into the Third Reich and in the General Government?

No. The lands incorporated into the Reich were subject to direct Germanization, because from the German point of view these lands were being returned to the motherland. The policy of the Germans was aimed at the rapid destruction of Polishness in these territories. In turn, the General Government was subject to a slightly different form of collective and individual repression, but the Church played the role of a victim in it.

So what were the repressions against the Church in the incorporated lands?

In October 1939, a massive and very dramatic enforcement of the Germanization policy began. Priests from the Chełmno diocese and the Archdiocese of Poznań and Gniezno as well as from individual dioceses located in the area of the later Warta Region were arrested. As a result of these activities, by 1941, at least half of the priests from these dioceses were arrested, placed in concentration camps or murdered on the spot. We can find traces, for example, in Piaśnica and in the local forests, as well as other places of execution in Kashubia, where there are pits and graves dug following the execution of many victims, including Catholic priests and nuns. This form of repression was deliberate and designed to seriously impact the functioning of the hierarchical Church and clergy, and negatively affect the Polish population.

Another great wave of clerical arrests took place in the fall of 1941. As a result, five bishops and many hundreds of priests were killed, especially in the Dachau concentration camp, where a total of 861 priests were murdered. Among them were outstanding pastors, and blessed priests such as Edward Detkens of the St. Anna Church in Warsaw, and Stefan Frelichowski, assistant scoutmaster, and today the patron of scouts.

The attack on the people of the Church from autumn 1939 was also accompanied by other forms of repression. Priests who remained in the areas of the annexed territories were either exiled to the General Government or were arrested. According to German orders, the mayors could keep only two priests in their area, which should have been enough for the local population. But they still had to sign the volkslist. German law entered into force immediately [after occupation], and all parishes needed to be German-speaking, which meant that it was impossible to celebrate services, pray in public and even confess in Polish. It was a severe repression resulting from the basic plan of the total Germanization of the people living in these areas.

Anyway, the Germans immediately began fighting not only the people of the Church, but also the Polish Catholic culture in these areas. Namely, first of all, the confiscation of all Polish goods that were in the churches. Not only were bells confiscated, which were melted down for the needs of the army, but the churches in general were closed, desecrated or very often demolished not only through mindless destruction, but also in the form of “taking into security”, as the Germans said, all cultural[ly important] goods, i.e. de facto transporting them deep into the Reich. German art historians were heavily involved in this process in order to assess the value of Polish monuments. It is true that some of these churches were opened later, but a significant part (such as the cathedral in Pelplin) did not open until the end of the German occupation.

How did the Holy See try to react to such actions by the Germans?

The Vatican started negotiations through the Apostolic Nuncio in Berlin, Cesary Orseniga, in an attempt to maintain the operations of the Roman Catholic Church in this area. These efforts were contested by the Polish government-in-exile, which supervised the course of these negotiations through its ambassador to the Holy See, Kazimierz Papée. The Holy See found itself in a difficult situation. On the one hand, it was being subjected to pressure from the German side, saying that Catholicism in these areas could only be German, and on the other hand – from the Polish side, which defended the letter of the 1925 concordat.

The Pope made a difficult choice – he agreed to appoint in the Chełmno diocese, the area most affected by repressions, an apostolic administrator, Carl Maria Splett, the bishop of Gdańsk. unlike his predecessor, he was a German who, unfortunately even before 1 September 1939, had clearly manifested his attachment to the Third Reich. Simply put, he was an anti-Polish bishop. In the Archdiocese of Poznań and Gniezno, the Holy See agreed to appoint a special vicar who would be responsible for pastoral care for the Germans who came to these areas as part of Germanization. In practice, however, the Vatican had no influence on the destructive German policy.

It is also worth saying that Arthur Karl Greiser, the governor of the Third Reich in the Wielkopolska region, was given the task of atheising this area by Adolf Hitler, himself. Wielkopolska was supposed to be an experimental case that would enable the liquidation of the Catholic Church in the entire territory of the Third Reich in the near future.

What was the situation of the Roman Catholic Church in the General Government?

The repressions that were associated with the total depolonization of the incorporated lands also concerned the basic forms of repression present in the General Government. The German policy towards the Church in this area resulted from the German policy towards the Polish population. The Poles were to be a cheap workforce serving the needs of the war economy of the Third Reich. As a result, the Polish Roman Catholic population was subjected to various kinds of repressions resulting from this situation.

In the General Government, as in the incorporated areas, secular church associations were liquidated, e.g. Catholic Action or Caritas, which operated in parishes, albeit illegally, as well as pastoral care, such as academic pastoral care in the church of St. Anna in Warsaw, which began operating underground. Education in the General Government was also abolished, because the Germans believed that Poles should be allowed to study only in elementary schools, and that higher levels of education were not needed (except for selected vocational schools).

Thus, the activity of male and female religious congregations, which ran schools, dormitories and dealt with education, decreased. However, these congregations could continue to exist – they had their own religious houses and their physical space was secured. The Germans rarely entered the area of religious congregations or devastated sacred spaces. It was recognized that churches and dioceses had the right to function, just like church hierarchies. The activity of the Catholic Church in the General Government was relatively greater than in the areas incorporated into the Third Reich.

What did it result from?

The Archbishop of Krakow Adam Stefan Sapieha was a great authority in the Church and he was strongly active at that time. He maintained a cold but official relationship with the Governor General Hans Frank and represented the needs of the Catholic Church’s faithful by articulating his opposition to anti-Polish policy. This influenced the flexibility visible in German policy from the very beginning, for example in the fall of 1939 towards Jasna Góra – it was not devastated or the painting of Our Lady of Częstochowa was not destroyed. The Paulines, fearing such a scenario, even substituted a copy of the painting, securing the original [in a safe location] just in case. It was suspected that when the Germans entered Częstochowa, they would do what the Swedes wanted to do in 1655. Through negotiations, it was concluded that Jasna Góra was a space where, of course, pilgrims must not come, because pilgrimages were forbidden, but the Germans acknowledged that a certain sacrum existed in this space.

Adam Stefan Sapieha collaborated with the emerging Polish Underground State. He also used the space of the Church that was tolerated by the German occupier – he supported Adam Ronikier and the Central Welfare Council, i.e. the only organization permitted by the Germans on the Aryan side. The Church included this charity work in line with its long tradition. Sapieha also maintained the existence of a major seminary in Krakow, which was de facto operating illegally. Karol Wojtyła became one of the clergy. He also allowed priests to be transferred to underground chaplaincy structures. Priest and Colonel Tadeusz Jachimowski, the dean of the military chaplains of the Home Army, performed his function on the order and with the approval of the Archbishop of Krakow.

Sapieha also agreed to give preaching rights to selected priests going to forced labor camps in Germany together with the faithful, so that priestly service was present wherever Poles were. Thanks to this policy of Sapieha, the faithful had the chance to attend masses, receive the sacraments, and the Polish language was present in the churches.

Was the Church also involved in helping, inter alia, Jews?

This was one of the many forms of underground activity by priests during the occupation. Sapieha made a unique decision regarding the keeping of record books by parish priests. Books of births and deaths were subject to far-reaching falsification by the underground or directly by those in need. Record certificates for those hiding, in the case of Jews with Aryan appearance, were forged so that they could live “on the surface”. And from 1942, they were mostly Jews.

The Polish Catholic Church took a very active part in saving Jews. Religious congregations, especially female ones, hid Jewish children and adults in practically each of their houses (in the case of Laski, some Franciscan sisters of the Cross were of Jewish origin and continued to live there). Sister Matylda Getter from Warsaw was an intermediary, and through her hands, as through the hands of Irena Sendler, children and adults passed, who were then directed to Catholic families in Warsaw or the surrounding area (this is how Jews also ended up in my family’s estate in Szeligi near Warsaw).

The vast majority of bishops living in the General Government, except probably only one case, also personally supported the Jewish population by hiding Jews in curial houses.

This example inspired others. The clergy were well aware, in their conscience and through the examples of priests and bishops showing how to behave in the face of the Holocaust. This resistance to the German extermination policy and giving testimony was much more possible in the General Government thanks to the fact that the Catholic Church functioned within its structures.

What was the situation of the Catholic Church under the Soviet occupation?

When it comes to the Soviet repressions against the Church, we have two phases of this occupation – 1939–1941 and 1944–1945. In the first period, the clergy did not find themselves on the front lines of the harsh repressive Soviet course. Taking the example of the four deportations deep into the Soviet Union, we do not see that the clergy were treated as a class that would be liquidated, like the gentry or Polish state officials.

The Soviets approached the people of the Church in a more flexible way. This was due to the fact that they used other tools for depolonization and atheization than the Germans. In fact, from the beginning of the occupation, Soviet law was in force in the Soviet Union from 1918, i.e. the so-called decree separating the state from the Church. This was connected with the rapid confiscation of all church property in the former Eastern Borderlands of the Second Polish Republic and the liquidation of all structures of the Catholic Church, including religious congregations. The priest did stay in his diocese or parish, but formally it was neither a diocese nor a parish. Atheization took place by minimizing the activity of the existing religious congregations or priests, by depriving them of their material resources overnight, and above all the right to catechesis. Intrusive Soviet propaganda became the main tool of atheization.

Was this policy successful for the Soviets?

Atheization did not take place because priests repeatedly violated Soviet law. They continued to conduct religion lessons or even tried to go beyond the allowed scope of the functioning of the closed space of the Catholic Church. Soviet law prohibited not only teaching children and adolescents religion, but also moving around in priestly clothes and using public space to manifest religiosity. Priests or nuns and religious people also tried to enter into various underground structures.

Although the priests themselves were not subject to massive physical repression in the form of execution or deportation, we know of priests who supported those who were suffering. It is worth recalling the figure of Tadeusz Fedorowicz from Lwów, who, seeing that the faithful were being deported, made the decision to submit himself for deportation. He received consent from the Archbishop Eugeniusz Baziak to carry out pastoral activity wherever the Soviet railway took him. Other priests were also involved with the deportees – wherever there were labor camps, there were also Polish priests who tried to support them spiritually.

Did the attitude of the Soviets towards the Church change in the second phase of the occupation?

In 1944–1945 the Soviets were much more ruthless when it came to treating priests. Priests were arrested under various pretexts. The most glaring example of this repressive policy against the people of the Church was the arrest of Bishop Adolf Szelążek, who was accused in January 1945 of breaking Soviet law, and his trial was a legal curiosity. He was accused, inter alia, of conducting anti-Soviet activities as the bishop of Lutsk, i.e. the superior of the diocese in the Second Polish Republic, even before the war.

Are we able to estimate how many Polish Catholic clergy died during the war?

Under the German occupation – about two thousand Polish priests and religious people, as well as several hundred nuns. This is over 20% of the pre-1939 Catholic clergy. Many of them died only because they were priests, many because of their solidarity with the nation fighting for freedom, such as priests – chaplains during the Warsaw Uprising, present in partisan units or in the Polish Armed Forces. When we try to compare it with people of other intellectual professions, it is undoubtedly the most painful loss. The vast majority of the priests who died during the war belonged to those archdioceses and dioceses whose lands were directly incorporated into the Third Reich in 1939. This is the statistical dimension of this great sacrifice that Polish priests of the Roman Catholic Church made as part of their vocation.

Interviewer: Anna Kruszyńska (PAP)