The Battle on the Vistula was the biggest in the Polish-Bolshevik war of 1919–1920. The battle between the Vistula, Niemen and Bug Rivers still surprises with its dramatic action and unexpected reversals.

by Janusz Odziemkowski

After a series of Polish strategic failures in the war in 1919, in March 1920 the Bolsheviks developed a plan for destroying Poland. They aimed to open an offensive with the Western Front forces of Mikhail Tukhachevsky advancing on the Minsk-Vilnius-Warsaw line. At the same time, the Southwestern Front was to move on Lviv, then in the last phase of the operation would support Tukhachevsky in Warsaw.

To force the enemy into a decisive battle before they concentrated their forces, Józef Piłsudski made an alliance with the head of the Ukrainian nation, Symon Petlura, promising the Ukrainians to help build their sovereign nation, and to conduct an offensive against Kiev. On 7 May, the Poles took the city but the major part of the Red Army escaped over the Dnieper River. In response, Lenin ordered Tukhachevsky to strike from the north. The Bolshevik offensive was halted at the cost of part of the Ukrainian forces brought from Belarus. Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks reinforced the Ukrainian front with the First Cavalry Army of Semyon Budyonny, then opened the offensive, overrunning the weakened Polish lines on 6 June.

On 4 July 1920 in Belarus, a second offensive began by Tukhachevsky. Facing over twice as many Bolsheviks, lacking reserves, the Polish Army retreated. On 15 July Vilnius fell, on 24 July Polish defenses were broken at the Neman River, on 30 July the Red Army reached the Bug.

The Western Front success confirmed Lenin in his conviction that victory was foreordained. Thus the Communist dictator ordered the attack of the Red Army split. Along with the Warsaw objective, on 22 July a new objective appeared for the South-Western Front to conquer Hungary.

Tukhachevsky, certain the main Polish forces concentrated for defense of the capital and north of the Bug, sent a wire to his army on 10 August to force the Vistula and take Warsaw. The Fourth Army and the Third Cavalry Corps (five divisions and a brigade) received orders to force the lower Vistula and cut off communications with Gdańsk, where Polish Army supplies were arriving from the West. The Fifteen Army and the Third Army (nine divisions) were to operate north of Warsaw. Moving directly on the capital was the Sixteenth Army (five divisions), supported by the Third Army, tasked with forcing the Vistula from the Praga bank on 14 August. The front’s left flank was protected by the Mozyr Group (two divisions, one cavalry brigade).

Victory appeared days away. Meanwhile in Białystok, the Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee, composed of Communists sent from Moscow, awaited the fall of Warsaw to take over as the “Polish Red government.” Commanders of the Sixteenth Army had posters prepared threatening death to Warsaw’s inhabitants for attacks on Soviet power. Preparations were being undertaken for presenting Tukhachevsky with a commemorative saber at Plac Zamkowy, or Castle Square, for taking Warsaw.

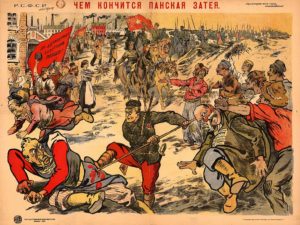

Europe didn’t believe there was any rescue for Poland. The prime minister of Great Britain, Lloyd George, lamented in the House of Commons that with the defeat of Poland the fruits of the Versailles Treaty would be lost. The Czech press published illustrations showing Polish nobility fleeing from the Bolsheviks and a Cossack with a whip running after a soldier in a Polish cap. In Germany, posters appeared with a Red Army soldier freeing the country from chains. Lord Edgar d’Albernon, member of the Interallied Mission to Poland, noted that nothing seemed more sure than that the Soviet Army would conquer Warsaw…

In Poland, that threat provoked a wave of patriotic feelings. On 1 August, the Council of National Defense was established, which proclaimed a call for the Volunteer Army. Conscription was supported by all the political parties with the exception of Communists, and the Church, social organizations, veterans of the January Uprising in 1863. 105,000 volunteers joined the army. Those incapable of fighting took up alternative service in the rear. Twenty regiments of volunteers were formed, and 28 battalions and 114 companies were sent as reinforcements to the front. They brought ardor and hope for victory to the exhausted army.

First, Piłsudski conceived a strike from the Brześć region against the flank of Tukhachevsky’s army. To safely transport needed forces from the Volhynia and Galicia districts, Poles attacked the cavalry forces at Brody and inflicted severe losses. However, on 1 August, Brześć fell, which set back plans for the Polish offensive.

Piłsudski rejected the counsel of Gen. Maxime Wegand from the French Military Mission, who thought that after 600 kilometers of retreat, the army wasn’t capable of attacking the enemy as “even the French soldier can’t do it,” and the suggestion of Entente advisers to defend the Vistula line. He didn’t mean to stop the Bolsheviks, but to crush them between the Vistula and Bug by a decisive maneuver and rapid action. He believed the Polish soldier was capable of doing it. Extremely helpful in this was fantastic work by counterespionage, which intercepted and decoded enemy wires.

On 6 August, the Commander in Chief discussed his plan with the Chief of Staff, Gen. Tadeusz Rozwadowski. The main strategy was a strike on the left flank and the rear of Tukhachevsky’s army at the Wieprz River by forces of the Central Front led by General Smigły-Rydz (the Fourth Army and part of the Third: five divisions, an infantry brigade and two cavalry brigades). The Northern Front of Gen. Józef Haller was to engage in battling the main Bolshevik forces. It comprised the Fifth Army led by Gen. Władysław Sikorski at the Wkra River (four divisions, one infantry brigade and a cavalry group and brigade), with the First Army of Gen. Franciszek Latinik defending Warsaw (five divisions, an infantry brigade), and the Second Army led by Gen. B. Roja (two infantry and cavalry divisions) along the middle course of the Vistula.

The government initiated negotiations, but the Bolsheviks, certain of victory, set conditions degrading Poland to the role of a vassal country and preparing to transform the nation into a new Soviet Republic (including a reduction of the army to 50,000 men).

On 13 August, the Sixteenth Army struck Warsaw, breaking the first line of defense and taking Radzymin to the north. The situation was dramatic, Bolshevik patrols reported they could see the lights of Praga. The mis-interpreted report reached their army’s commanders and from there it went to Moscow. The proclamation was created that the Red Army was entering Warsaw. This brought about an eruption among Germans in Upper Silesia and attacks on Poles, which ended with the outbreak of the Second Silesian Uprising. On 14 August, pitched battels were waged for Radzymin; soldiers in the Vilnius riflemen’s regiment attacked singing the soon-to-be national anthem, “Dąbrowski’s Mazurka.” In the battle for Ossów, the First Battalion of the 236th Infantry Regiment, composed of Warsaw school youth, stepped forth bravely. Father Skorupka perished, one of the heroes of the defense of Warsaw. On the next day, Poles recaptured Radzymin and the lost first line of defense with support of the air force, which attacked and demoralized the Bolshevik troops.

On 14 August, the Fifth Army struck at the Wkra River, led by General Sikorski. Taking advantage of mistakes by the enemy, double its size, it hit the Third and Fifteenth Armies, provoking frustration in Tukhachevsky, who saw events as “really appalling and unimaginable.” The Third Cavalry Corps and part of the Fourth Army were driven back to the lower course of the Vistula by Polish rearguard formations. The famous defense of Płock, north along the river, happened with its population supporting the army.

On 16 August, under command of Chief of Staff Rozwadowski, the offensive from the Wieprz River pushed off. Piłsudski demanded from the army maximum effort and to urge advance without glancing back. Infantry marched in full kit for 40 to 50 kilometers a day in great heat, overrunning the Bolshevik troops. It was a pace similar to motorized forces in the Second World War. Many soldiers passed out from exhaustion; put on supply vehicles for a rest, they rolled in the rear.

Tukhachevsky downplayed an order to counterattack found on a Polish soldier, taking it for disinformation aimed at drawing the Bolsheviks off their objective of Warsaw. He understood the dread of the situation on the evening of 17 August, with Poles advancing in the Sixteenth Army’s rear areas. The next day, the Polish First Army also launched an attack. For the next eight days, the Army of the Western Front tried to get through to the East, always overtaken and surrounded by Poles. With one encirclement broken, another and another formed. Polish soldiers, carried by enthusiasm, managed to make an effort that couldn’t be met or challenged even by their very durable enemy. Many feats were performed, in some of them Polish troops met serious losses, as was the case with the Siberian Brigade at Chorzelce. But the Western Front was annihilated, losing 70 percent of its personnel. Only the Fifteenth Army managed to withdraw to the East, with some rests for their troops. Into East Prussia some 45,000 to 80,000 Red Army soldiers escaped. Poles took around 70,000 prisoners, along with 231 cannon and much military equipment. Budionny, who’d been stuck in Lviv (under orders to march in invasion of Hungary) arrived with delayed aid for Tukhachevsky then was surrounded and beaten at Komarów.

The shattering defeat of the Bolsheviks facilitated Poles in continuing the war and led to its victorious end. To have lost at the Vistula would have meant the transformation of Poland into a Soviet republic, the murder of the nation’s elites, enforcement of a foreign system of values, years of absolute repression. If Poland had fallen, the Bolsheviks would have join the German revolution and broken the Versailles Treaty by redirecting Europe on different tracks. On 20 September, Lenin said “Piłsudski and his Poles triggered a gigantic, astonishing disaster for the world revolution.” For its long-range results, Frenchmen compare the Battle of the Vistula to the Miracle of the Marne, which in 1914 had rescued France, and Lord d’Abernon named it the eighteenth decisive battle in the history of the world.

The catastrophe of the Red Army is often called the Miracle on the Vistula. This description was used in 1920 by Stanisław Stroński to picture the hopeless situation of the nation, then after the victory it took on an unexpected meaning. There is no other victory in the history of Poland that was, apart from soldiers’ efforts, so supported by the broad civilian population. General Weygand stated that the “heroic Polish nation rescued itself.” The memory about the Miracle on the Vistula left a deep trace in our means of defining the history of Poland and its place in Europe, and helped fortify society through subsequent years of disaster and occupation.

Author: Janusz Odziemkowski – Polish historian, professor, lecturer, former director of the Council of War Veterans and Victims of Oppression. Associate professor at the Historical Institute at the Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University, co-operated also with National Defense University, where he created the European Studies program. He researches on universal history and history of Poland in 19th and 20th centuries, political history and Polish society in 19th century, also military history and of armed conflicts