On the occasion of subsequent papal conclaves, photo agencies would compete to catch cardinals electing the successor of Saint Peter. Even after the reforms of Vatican II, the garments of Church dignitaries and the ceremonies accompanying the new pope’s assumption of office remain baroque in style. In 1978, however, greatest interest was generated by quite different photos: the leaders of communist parties from both Poland and the USSR in their clumsy suits. These leaders perceived the presence of a Pole on the papal throne as a threat and a challenge. As it turned out – they had a good reason.

by Wojciech Stanisławski

Détente around the world

The second half of the 1970s was dominated by détente, both in global politics and in Poland. The great powers – the USA and the USSR – were holding disarmament talks, the countries of the communist bloc had signed a number of documents from the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, the notion of “convergence” first appeared in newspapers, i.e. the similarity of two political systems that had so far remained locked in this Cold War conflict. Also in Poland, after a decade and a half of stagnation associated with Władysław Gomułka’s rule, the new First Secretary of the Communist Party, Edward Gierek, would announce economic and social modernization after coming to power in December 1970. This would be followed by – although it was not directly announced in any way – a certain liberalization of the communist cultural and religious policy.

Indeed, the contrast with Gomułka’s policy was clearly noticeable in the first half of the 1970s. This was also experienced by the Church in Poland, which had suffered quite a bit during the reign of Gomułka (1956-1970). Even the new First Secretary of the communist party came to power on a wave of “anti-Stalinist reaction” and never resorted to the terror of communist rule in the first half of the 1950s, the Church remained one of his primary political opponents. Gomułka’s team did not limit themselves to mere disputes over ideology and “superstructure”, but were decided on a brute force confrontation. In 1956-1970, it was not allowed to build new churches nor to take over church property, which often led to clashes between the faithful and the security forces (Zielona Góra, Nowa Huta, Kraśnik, Przemyśl).

That period was also marked by a dispute over the interpretation of the Polish state’s millennium, which dates back to the act of baptism by Mieszko, the first historical ruler of the 10th century. Thus, the authorities competed to organize alternative celebrations to overtake the church’s Millennium, and repressed or beat participants of church ceremonies. The authorities developed structures for clergy surveillance and the political police tried to recruit as many secret collaborators as possible from among the clergy.

At the same time, the communist authorities did not give up on more subtle forms of political games aimed at weakening the Church. They differentiated support for individual groups of lay Catholics, which ranged from the openly pro-government (PAX Association) to those strongly distanced from the authorities (such as “Znak” circle). They also tried to communicate with the Vatican, bypassing Cardinal Wyszyński, or argued with other bishops, including the Krakow Metropolitan, Archbishop Karol Wojtyła.

Liberal Edward Gierek

Compared with these efforts, Edward Gierek’s team built their relations with the Church in a way that was incomparably more correct. They did not disturb church processions. There were no confiscations of any goods. Congratulatory letters were being exchanged on the occasion of birthdays. In August 1976, Edward Gierek sent such a letter on the 75th anniversary of Primate Wyszyński, and the latter reciprocated with a similar gesture a year and a half later on the 65th birthday of the first secretary of the communist party. There were even still a few deputies in the Sejm of the Polish People’s Republic who officially represented lay Catholics – this was unthinkable in any other country of the Eastern Bloc.

Can we say it was an idyll then? No. The Church, to which the overwhelming majority of Polish citizens belonged, continued to be “greatly absent” from the media and education programs which were under the absolute control of the state. In 1973, under Department IV of the Ministry of the Interior, which was fully responsible for controlling and combating church structures, a separate operational group for special tasks was established, whose aim was to misinform and disintegrate church circles. The authorities also continued to split secular Catholic circles, supporting those with nationalist sympathies. Another game was played by the party at the level of international diplomacy: just as in the previous decade, the communists tried to establish a direct communication with Vatican diplomats, “over” the heads of the Polish Primate and Episcopate. This is why the head of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Stefan Olszowski, visited Pope Paul VI in the summer of 1973.

At the same time, however, several other processes were taking place in Poland. The modernization of the economy and the country, announced by the new First Secretary of the Party, began to slow down due to the mismanagement of loans obtained in the West. Debt started to build up. The pace of building new houses slowed down, and the recession became more visible. This, coupled with price rises and the shortage of staple foods in the market, began to frustrate workers.

The liberalization of the cultural policy declared by the authorities was conducive to the functioning in public life of many initiatives and circles that had a very casual attitude towards Marxism and the official cultural policy of the state. The milieu of creators issued open critical letters to the authorities more often. Such initiatives were fostered by the agreements of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe signed by the authorities of the People’s Republic of Poland. The authorities conceived it mostly as a propaganda act but nevertheless, it imposed certain restrictions and obligations on them. A peculiar accumulation of para-opposition activities and social protests took place in the summer and autumn of 1976. When in June, the workers of a dozen workplaces protested against the rise in food prices, the authorities reacted as usual – with repressions, beatings and arrests. Several groups of intellectuals, scientists, writers and students with an opposition orientation established the Workers’ Defense Committee, which is considered to be the beginning of open political opposition in the Polish People’s Republic after the end of the Stalinist era.

The Church in Poland was somewhat “adjacent” to these processes: it was in conflict with the authorities not so much in terms of politics as in terms of worldview, striving first of all to secure the right to fulfill its basic mission to proclaim the Gospel. At the same time, however, both the church hierarchies (including, above all, Primate Wyszyński) and rank clergymen contributed to minor, organic changes in freedom. In March 1973, the Episcopate, responding to changes in education, emphasized the right of parents to raise children in accordance with their worldview. A year later, in the series of sermons delivered at St. Cross Church in Warsaw the primate emphasized the importance of human and national dignity. In 1977, activists and sympathizers of the Workers’ Defense Committee began to organize hunger strikes in Warsaw churches, publicizing the repression of the authorities.

Conclave and shock

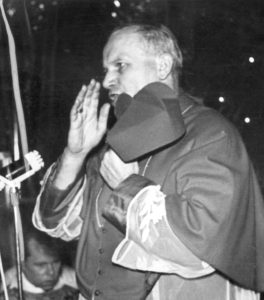

It is doubtful that the 111 cardinals-electors from all over the world, who had gathered on 15 October 1978 in St. Peter Basilica had such detailed knowledge about the situation of the Church in Poland. They knew that it was the only country of the “Eastern Bloc” in which the vast majority of citizens declared that they belonged to the Church and regularly participated in religious life, while the authorities were forced to ease repression and seek consensus with the Church. They were probably familiar with the history of the last few decades: a large number of cardinals participated in 1973 in the beatification ceremony of the Polish monk Maksymilian Maria Kolbe, martyred in the Auschwitz concentration camp, and knew about the imprisonment of Primate Wyszyński during the years of Stalinism. Certainly, the vast majority of them were aware of the competence, energy and personal charisma of one of the younger electors, 58-year-old Archbishop Karol Wojtyła.

His election to the Holy See, after eight rounds of voting, in the late afternoon of 16 October 1978, was an extraordinary event also in the history of the universal Church. For the first time in 455 years, a non-Italian became the pope, for the first time it was a resident from a country outside Western Europe and one which was, from its point of view, a bit peripheral. The fact, however, was that it was a country located “behind the Iron Curtain ” that had experienced an exceptionally dramatic history in the 20th century – all of this gave this choice an additional meaning. Wojtyła became, undoubtedly, the “man of the year” – although the weekly magazine Time awarded him this title only in 1994.

For the faithful, the political dimension of the election of a new head of the Church was of secondary importance. On the other hand, for Polish and Soviet apparatchiks, he undoubtedly remained in the foreground. The authorities of the People’s Republic of Poland put on a brave face by issuing a congratulatory letter on the decision of the conclave, which “brought Poland satisfaction”, because “the son of a nation building the greatness and prosperity of its socialist homeland” sat on the Chair of St. Peter. The greetings from the Soviet Kremlin were spoken through clenched teeth.

Primate Wyszyński and other Church hierarchies in Poland, apart from joy, pride and gratitude, expressed their relief in internal conversations. “I have lost a great friend and close associate. But at the same time, I gained something, because I won’t have to explain [in the Vatican] the situation of the Church in Poland for a long time,” Wyszyński noted in his private notes.

And what about “ordinary Poles” for whom the election of the Polish Pope was a big event on many levels all at the same time – patriotic, religious and political? Well, the Poles went mad with joy. At 7.00 p.m. in the former royal castle in Wawel in Krakow, the 16th-century Sigismund bell – rung only in extraordinary circumstances – began to ring. All preserved accounts – memoirs, amateur photos and films – tell of crowds going out into the streets, about spontaneous parades with national flags, singing religious songs and hymns, about people embracing each other. No historian or sociologist, even those personally strongly distanced from the Church, can deny the social mobilization and the “sense of bond” that the election of John Paul II created on the Solidarity revolution, which happened less than two years later.

Those days of October 1978 were recorded in dozens of memories and poems – most of them very sublime, emphasizing the solemn dimension of that time, the fulfillment of the “prophecies” of the 19th-century Polish Romantic poet, Juliusz Słowacki, who proclaimed the vision of a “Slavic pope” during the ongoing partitions of Poland. Who knows, however, whether the unique mood of those days is best reflected in a fragment of a poem by Zbigniew Machej – an ironic and slightly libertine poet, widely known for his poetic admiration of the beauty of Czech women. In the collection Wspomnienia z poezji nowoczesnej (Memories of Modern Poetry, 2010), recalling his youthful admiration for poetry by T.S. Eliot, he wrote:

And that autumn was for Poles

very peculiar

as the prophecy of Juliusz Słowacki

came true

about the Polish Pope

thus on that sixteenth day

in October of that peculiar autumn,

everyone wandered around Krakow intoxicated

with white smoke blown from conclave held in Rome

by the angel’s lungs and the wind of history

everyone walked around repeating crescendo

the anti-Soviet mantra “habemus papam,

habemus papam”. And with this unclear mantra

they were wonderfully uplifted

and they could hardly sleep even in the autumn darkness

(…)

Some already knew already then

that the end is coming

of that world, of those languages

and that story

with its secret passages

and emergency exits

Indeed, as it turned out, the election of John Paul II meant the beginning of the end of “that history” for Poles.

Author: Wojciech Stanisławski

Transation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin