The peace concluded between the Republic of Poland, of the one part, and Soviet Russia and Ukraine, of the other part, brought political order to the territories between the Baltic and Black Seas for 18 and a half years. Eventually, Hitler’s ally Moscow declared it ‘null and void’.

by Wojciech Stanisławski

Who knows, maybe it should be written about next to the ‘big five’ peace treaties concluded after the First World War? Versailles (June 1919) with Germany, Saint-Germain-en-Laye (September 1919, Austria), Neuilly-sur-Seine (November 1919, Bulgaria), Trianon (June 1920, Hungary) and Sèvres (August 1920, Turkey). Why not add ‘Riga, March 1921, Russia’ to the list?

There are arguments that would support doing this. The Peace of Riga, like the above-mentioned five peace treaties, brought order to the state of affairs after the Great War, as well as after the armed conflict that had already broken out after the armistice in November 1918. Like Versailles, Neuilly and Trianon, it represented an agreement not only on the final cessation of wartime operations and the demarcation of a permanent frontier, but also regulated a whole package of matters relating to reparations, exchange of prisoners of war, return of cultural property, etc. Just like them, it did not survive twenty years.

Yet it is a unique phenomenon in the history of diplomacy. Firstly, because it was an agreement between two states parties (four, if one considers the rather illusory sovereignty of the Ukrainian and Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republics), and not between the Entente bloc and one of the Central Powers. Secondly, because it regulated issues that sometimes dated back to 1795, and defined Poland’s eastern border for the first time in 126 years. Thirdly, because neither Soviet Russia (as of December 1922: the Soviet Union) nor Poland was a party to the global conflict that broke out in 1914. Both these states were able to rise on the wave of destabilisation that the world war brought.

Delegation waiting at the border

It was also significant that the treaty itself was ultimately a product of truce negotiations conducted in dramatic circumstances. Let us recall: in July 1920, the Soviet offensive develops across the ‘eastern wall’. Moscow rejects the peace initiatives of France and Great Britain (very unfavourable for Poland) formulated at a conference in the Belgian resort of Spa on 11 July. The commander of the south-western front, Alexander Yegorov, is ordered to march on Krakow, and that of the north-western front (Mikhail Tukhachevsky) to capture Warsaw. The Polish government sends further proposals for peace talks, but the Soviet side is not willing to accept them. The first delegation to the talks (headed by Władysław Wróblewski) waited in vain for contact to be made.

The second, headed by Deputy Foreign Minister Jan Dąbski, was kept ‘on the border’ for a week until the start of negotiations in Minsk on 17 August. Even then, however, the Soviet delegation was headed by Jūlijs Daniševskis, known mainly for his draconian sentences as chairman of the Revolutionary War Council of the RSFSR. This was an obvious affront.

In the meantime, however, the situation at the front, 500 km away, changed dramatically. After the Soviet troops were stopped at the line of the Narew-Vistula-Wieprz Rivers on 16 August, a counter-offensive took place from the Wieprz River. Combined with the stretching of the Soviet lines of communication and the breaking of the Red Army’s radio communication ciphers by the Poles, this led, after the failure of the offensive on Warsaw, to a retreat that was becoming more and more panicky by the hour. On the same day, ‘The ‘Mozyr’ Group, which formed the core of the attack on Warsaw, was broken up, and two days later Budyonny’s Mounted Army, attacking from the south, and Gaya Gai’s Mounted Corps, attacking from the north, were forced to retreat. Members of the Polish delegation present in Minsk reported the almost slapstick-comedy change in the attitude of the Bolsheviks, who within a dozen or so hours went from being boorish, through anxiety, to ostentatious politeness. Behind this effect, however, were struggles of armies numbering many thousands.

In the new strategic and political situation, the negotiations were suspended, and then resumed on neutral ground – in Riga, the Latvian capital (Minsk was already within range of Polish artillery by that time). In fact, the negotiations began with the signing of a ‘preliminary peace agreement’, i.e. a ceasefire between Poland and the Soviets. It was signed on 12 October 1920, and six days later military action finally ceased. The army stood with arms at its feet: the time of diplomats had arrived.

Badly overdue accounts

It was the time of diplomats, but also of strategists: it should be recalled once again that the planned peace treaty was to put an end not only to the armed struggles of the last two years taking place between the Neman, the Berezina and the Dnieper (which was trench warfare in 1919 and escalated sharply in 1920), but also to a fundamental political dispute. It was a question of establishing a political order for the strip of land between the Baltic and the Black Sea in the vacuum created after the collapse of the Russian Empire.

There were a number of contenders for the role of creators of such an order. Among the most important were Soviet Russia and the Republic of Poland. Let us briefly list the others: the supporters of ‘non-Bolshevik’ Russia, who incidentally tended towards different political concepts, were for the most part no longer of any military significance: General Wrangel’s troops were still holding on in the Crimea, while Boris Savinkov was trying to create small formations advocating a ‘third Russia’ (non-tsar and non-Bolshevik) at the side of the Polish Army.

The Baltic states were content with their regained independence, not claiming any major territorial acquisitions (the dispute between Lithuania and Poland was still ongoing). The Belarusians proved too weak to create serious state structures in the chaos of 1917–1920: some counted on the generosity of the Polish side, others on that of the Soviets. The same applied to the Ukrainians, although their political potential was greater. Poland’s political and military ally was the government of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UPR) headed by Symon Petliura, while on the Soviet side there was the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (USSR).

Most important, however, were the positions of the two main actors, Poland and Soviet Russia. On the surface, these states had little in common with their predecessors. The Bolshevik leaders saw their country as the negation and antithesis of the tsarist state, and in 1918 they officially renounced ‘claims to Belarusian, Ukrainian and Polish lands’ and invalidated the 18th century partition treaties. Poland was referring to the heritage and ‘spirit’ of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but it was obvious to everyone that it was impossible to think of a simple restitution of the state liquidated in 1795, either in terms of the system or territory. Far too fundamental were the social, political and national transformations that had taken place on the historical territory of the state during the 123 years of captivity.

Reality was more complex than declarations: Moscow de facto hesitated between accepting an independent Poland within its ‘narrowly ethnographic’ borders, or incorporating it into the structure of satellite ‘people’s republics’, closely subordinated to Soviet Russia. By the ‘ethnographic border’ Russia meant roughly Poland ending on the Bug River: customarily (though inaccurately) this border line is referred to in historiography as the Curzon Line. This was the position taken by Soviet diplomats as late as in spring 1920; at that time, however, revolutionary enthusiasm and the slogan ‘over Poland’s dead body to the West!’, officially formulated by Tukhachevsky in early August 1920, were already gaining ground in Moscow.

Poland deeply divided

The Polish political elites were deeply divided as regards the concept of the borders of the reborn state. The pre-partition borders of 1772 were in everyone’s (nostalgic) memory but the attitude to them was determined by the concept of state and society. Politicians and thinkers supporting the notion of a (uni)national state, who regarded it as the basis of political life, were in favour of giving up the easternmost territories. In their view, it would be impossible to ‘polonise’ the Belarusian and Ukrainian populations dominating in this area while the very process seemed to them a sine qua non condition for the efficient functioning of the state.

A completely different position was taken by leaders and strategists thinking in terms of the state and its system, attached to the memory of the Republic of Many Nations (i.e. pre-partitions Polish Commonwealth) and open to the possibility of autonomy for other nations within the borders of the reborn state, or the creation of a federation of states under the aegis of Poland. The most serious supporter of such a solution was the Head of State Józef Piłsudski. In the autumn of 1920, despite the authority enjoyed by Piłsudski after the invasion had been repulsed, it was his opponents – supporters of the nation-state – that were more popular in political terms.

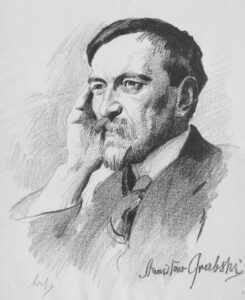

This division, fundamental for Polish politics in the first half of the 20th century, also found its expression at the negotiating table in Riga. The Polish delegation to the negotiations appointed by the Sejm was dominated by politicians of the National Democracy, headed by Stanisław Grabski, one of the most eminent politicians of that camp. There were only a few ‘Piłsudski’s men’ there, led by Leon Wasilewski. These usually either came from the Intermarium area, or had been involved in the notion for many years. It is significant that it was the aforementioned Leon Wasilewski, although a Polish nobleman by origin, who drafted the final Ukrainian version of the treaty – as he spoke that language better than any of the Soviet negotiators, formally representing the USSR. That did not mean much, however. ‘Piłsudski’s men’ were able to bring their competence – and powerlessness – to the negotiations.

Abel behind the cordon

The provisions of the treaty were therefore determined by the proportion of Polish and Russian forces after the cessation of armed operations, but also by the Polish negotiators’ firm choice of the ‘minimalist’ version. The Polish side included most of the territories that had belonged to the Commonwealth until the Second Partition (1793). However, contrary to the usual practice of territorial negotiations, in which both sides strive for every inch of ‘their’ land, the Polish negotiators more than once gave up the territories the Soviets were ready to give up. With a broad gesture, Stanisław Grabski ‘ceded’ Minsk to them – and hundreds of localities still culturally and economically linked with Poland. Never mind their precise names. On the Soviet side, there remained hundreds of thousands of people who felt Polish citizens, whose fate was soon to prove tragic. The cry of ‘Cain Grabski!’ uttered from the gallery of the Sejm during the ratification of the Peace of Riga by the Polish Parliament was merely an expression of helplessness.

Politically, the most significant thing, apart from the border issue, was Warsaw’s recognition of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. No matter how fictitious that statehood was and how illusorily it represented the interests of the Ukrainians (there could hardly be a clearer example of this than the Holodomor (Terror-Famine) staged by USSR officials) – Having recognised it, Poland gave up its intentions to support other forms of Ukrainian statehood. In an ad hoc way, this meant Poland ‘renouncing’ its Ukrainian allies from the UPR: disbanding their troops and withdrawing the recognition of Petliura’s government.

In the perspective of twenty years of independence, this meant a permanent problem with a frustrated Ukrainian population of several million, looking to Kharkiv and Kiev. In the geopolitical perspective, let us call it that way, it prevented the creation of a counterweight to Moscow and delayed the emergence of an independent Ukrainian state by 70 years. In proportion, the same problem affected the much less numerous Belarusian and Russian elites active in Poland. They, too, felt betrayed, or at least abandoned, in Riga, and their trust in Warsaw diminished considerably.

Champagne at the House of the Blackheads

As if to wipe away the tears, other provisions of the treaty were adopted, concerning compensation for Poland after a century of annexation, the return of libraries, museums, collections and other cultural assets seized in Poland, and the possibility of ‘repatriation’ for those who would declare a desire to obtain Polish or Soviet citizenship.

In the end, Soviet Russia did not pay any compensation. It was possible to recover a considerable part of cultural property, above all old prints and paintings, the Wawel arrases and the only surviving Polish coronation insignia – a medieval sword, called Szczerbiec. However, a significant part of the book collection of the pre-partition Załuski Library remained in Saint Petersburg, and no one tried to count the Polish jewels. Managed in the face of strong resistance from the Soviet side, repatriation was virtually halted by Moscow after 1925. Of the 1.2 million USSR citizens declaring themselves Polish, more than 130,000 were killed in the NKVD’s ‘Polish Operation’ carried out between 1937 and 1938 (about 110,000 were shot at the back of the head and more than 20,000 died in labour camps), most of the others were sent into exile or brutally Russified.

The negotiations took place in the House of the Blackheads (Schwarzhäupterhaus), a gothic building whose name recalls Riga’s Hanseatic past. At the banquet that followed the signing of the treaty, champagne was poured in abundance. Stanisław Grabski was having the best time, blissfully unaware that the border line ‘along the Dvina river (…) continuing along the border of the former Vilnius and Vitebsk governorates to the road connecting the village of Drozdy with the town of Orzechowno’ (and so on for six pages) is nothing more than a rut left in the soft soil by the wheel of History. Or, to put it less poetically, an ephemeral ceasefire. This was conclusively proven by Vladimir Potemkin, deputy minister of Soviet diplomacy, eighteen and a half years later. At 3 a.m. on 17 September, he handed a note to the Polish ambassador in Moscow, Wacław Grzybowski, in which he declared all previously concluded agreements with Poland null and void, and the Polish state non-existent. Red Army tanks were already entering Poland at that early hour.

Author: Wojciech Stanisławski

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki