The date of 17 September is one of the worst in the ‘Polish calendar’; one of those that marks moments of a total loss of hope on the scale of the entire nation. On 17 September 1939, it turned out that Poland – reborn briefly after a century and a half of partitions – was this time being annihilated by two totalitarian systems acting in unison against it.

by Michał Bronowicki

The threat of ‘17 September’ had been growing for years – from both sides. The Germans, unreconciled with the results of the First World War, questioned the terms of the Treaty of Versailles from the outset, seeing Poland as a parasite state fattened on ‘German injustice’ – from where the Nazi resentment of the Slavs must also have grown. The Soviets regarded the ‘Great Poland’ as an extremely hostile state and, moreover, following their defeat in a direct clash in 1920, had awaited the right moment to avenge the ‘Soviet wrongdoings’…

Interwar Poland was unable to find a way against this terrible pressure of both expanding and aggressive totalitarian systems. The country’s leaders were unable to foresee their agreement; we were not ready either for a blow from the west or one ‘in the back’ – from the east. We had to lose. Also because nobody in the world was capable of stopping these greedy, militarised ideologies: communism and Nazism.

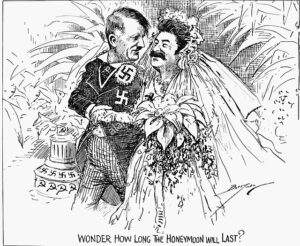

Stalin and Hitler formed an alliance – as it turned out – only for less than two years. Joining against Poland, their forces finally turned against one another. Fortunately for the world, which in the face of their longer-lasting alliance may – like Poland – have proved helpless. (Z.G.)

Joseph Stalin (General Secretary of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of the Bolsheviks) during a meeting of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee:

The issue of war or peace has entered a critical stage. Its solution depends solely on us. If we conclude a treaty with England and France, Germany will be forced to abandon its plans of aggression, to yield to the Polish position. It will also seek to arrange relations with the Western powers. This way, we will be able to avoid the outbreak of war, but further developments would then go in a direction that would be inconvenient for us. On the other hand, if we accept the German proposal to conclude a non-aggression pact with them, this will enable Germany to attack Poland and thus the intervention of England and France will become a fait accompli. Once this happens, we can usefully await the right moment to join the conflict or to achieve our objective by other means. The choice is therefore clear to us: we should accept the German proposal, and send the French and English military missions politely home…

Moscow, 19 August 1939 [1]

Adolf Hitler (Chancellor of the Third Reich) in a cable to Joseph Stalin:

To me, the conclusion of the Non-Aggression Pact with the Soviet Union means establishing a long-term German policy. Germany is thus returning to a political line that has benefited both countries in past centuries.

[…] The tension between Germany and Poland has become unbearable. Poland’s attitude towards the great power is such that a crisis could occur at any moment. In the face of this insolence, Germany is determined to guard the interests of the Reich by all means.

Berlin, 20 August [1]

Joseph Stalin in a cable to Adolf Hitler:

The peoples of our countries need peaceful mutual relations. The consent of the German Government for the conclusion of the non-aggression pact is the basis for the elimination of political tension and establishment of peace and cooperation between our countries.

The Soviet Government has authorised me to communicate to you that it agrees to the arrival of Mr [Joachim] von Ribbentrop in Moscow on 23 August.

Moscow, 21 August [1]

From the non-aggression treaty between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics:

Driven by the desire to strengthen the issue of peace between the USSR and Germany, and guided by the essentials of the neutrality agreement concluded between them in April 1926, the Government of the USSR and the Government of Germany have reached the following agreement:

Article 1. Both Contracting Parties shall undertake to refrain from all violence, all aggressive action and all onslaught in their mutual relations, both independently and jointly with other powers.

Moscow, 23 August [28]

From the secret additional protocol of the Germany-Soviet agreement:

In the event of territorial or political changes in the territories belonging to the Polish State, the boundary of the zone of interest of Germany and the USSR will follow approximately the line of the rivers Narew, Vistula and the San. The question whether it will be desirable in the interests of both Parties to maintain an independent Polish State and within what boundaries, can only be finally clarified in the course of further political developments. In any case, both Governments shall settle this matter by means of an amicable agreement.

Moscow, 23 August [28]

Adolf Hitler in a proclamation to the German army:

The Polish state has not agreed to a peaceful settlement of relations, as I had wished, and has resorted to arms. Germans living in Poland are being persecuted, bloody terror is being used against them, and they are being expelled from their own homes. A series of border violations, which cannot be tolerated by a great power, shows that Poland no longer intends to respect the borders of the Reich.

In order to put an end to this madness, I have no choice but to answer with force against force. The German army will fight adamantly for the honour and vital rights of a revived Germany. I expect that every soldier, mindful of the great traditions of Germany’s age-old soldierly virtues, will always be aware that he represents the Great National Socialist Germany. Long live our people, long live our Reich.

Berlin, 1 September [24]

Joachim von Ribbentrop (Foreign Minister of the Third Reich) in a cable to Friedrich von Schulenburg (German Ambassador in Moscow):

We expect that the Polish army will be completely broken up within a few weeks. The territory we have established in Moscow as a German zone of interest will therefore be occupied by us militarily. But, for military reasons, we will have to enter those Polish territories belonging to the Russian zone of interest in order to pursue units of the Polish army.

Please discuss this matter immediately with Molotov and determine when the Soviet Union will deem it necessary for the Russian armed forces to be used to act against the Polish armed forces in the Russian zone of interest, in order to take possession of this territory. For us, this would not only be a relief, but also acting in the spirit of the Moscow accords, and in the Soviet interest.

Berlin, 3 September [1]

Vyacheslav Molotov (People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs of the USSR) in a conversation with Friedrich von Schulenburg:

We are united in the opinion that, at the appropriate moment in time, we will unconditionally have to initiate concrete measures. However, we are of the view that this moment has not yet arrived. It is possible that we are wrong. However, it seems to us that too much haste may harm the cause and contribute to the unification of the opponents.

Moscow, 5 September [1]

Stefan Brzeszczyński (Polish Military Attaché in Moscow):

From time to time, mass rallies were held at Gorky Park, at which an official speaker highlighted the current international political situation, naturally from the Soviet point of view. […]

Such rally was to take place on 8 September 1939 at 2 pm. So I arranged with three friendly military attachés, English, American and Finnish, to attend together, as the German-Polish war was to be discussed. We all spoke fluent Russian.

The speech was unfavourable to the Poles and the assembled people received it rather coldly. They only became animated when, towards the end of the speech, the speaker shouted in a raised voice: ‘And what, are we, the Soviet people and government, to look on passively at the suffering of our brethren Byelorussians and Ukrainians through the fault of your Poland?’. Admittedly, the speaker did not provide an answer to this question, but the assembled people understood it in their own way, namely, that Soviet troops would go to the aid of Poland! Almost everyone shouted: ‘W pochod, w pochod protiv Giermancam!’ [Let’s go, let’s go against the Germans!]. Once we got into the car, the English attaché, Colonel Firebrace, asked me what I thought of the speaker’s final query. I replied almost without thinking: ‘Tsarina Catherine once sent her troops against the Poles under the pretext of protecting dissidents, and now Stalin will send his under the pretext of defending his fellow countrymen and take half of Poland.’ All three nodded their heads in sadness.

Moscow, 8 September [34]

From Friedrich von Schulenburg’s report to the Foreign Ministry of the Third Reich:

At today’s conference […] Molotov amended his statement of yesterday, saying that the Soviet Government had been taken completely by surprise by the unexpectedly rapid German military successes. According to our first communiqué, the Red Army had been hoping for several weeks, which have now been shortened to a few days. The Soviet military authorities found themselves in a difficult situation, as they still needed some two to three weeks to prepare due to the conditions here. Over a million people had already been mobilised.

I painstakingly explained to Molotov how decisive a quick action by the Red Army would be in the present situation. Molotov repeated that everything possible was being done to speed up the action. I got the impression that Molotov had promised more yesterday than the Red Army is capable of.

Moscow, 10 September [24]

Friedrich von Schulenburg in a cable to the Foreign Ministry of the Third Reich:

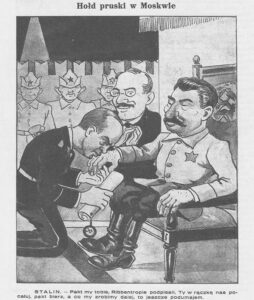

Molotov invited me to see him at 4 pm today and declared that the readiness of the Red Army had been achieved faster than expected. Therefore, the Soviet action might take place earlier than he had assumed at our last meeting. For the political substructure of the Soviet incursion (the disintegration of Poland and the protection of the ‘Russian’ minority), it would be of the highest value to go into action only if the Polish capital, Warsaw, fell. Molotov therefore asked to be told as soon as possible when one could count on the seizing of Warsaw.

Moscow, 14 September [1]

From Friedrich von Schulenburg’s report to Joachim von Ribbentrop:

Stalin received me at 2 am in the presence of Molotov and Voroshilov, and declared that the Red Army would cross the Soviet border this morning at 6 am along the entire line from Połock to Kamieniec Podolski.

In order to avoid misunderstandings, Stalin urgently requested that German aviation not cross the Białystok-Brzeć-Lwów line eastwards as of today. Soviet aircraft will begin bombing areas east of Lwów today.

Moscow, 17 September [28]

Vyacheslav Molotov, in a note to Wacław Grzybowski (Polish Ambassador in Moscow):

The Polish-German war has revealed the internal bankruptcy of the Polish state. Within ten days of military operations, Poland has lost all its industrial regions and cultural centres. Warsaw has ceased to exist as the capital of Poland. The Polish Government has disintegrated and is showing no signs of life. This means that the Polish State and its Government have effectively ceased to exist. As a result, the treaties concluded between the USSR and Poland are no longer in force. Left to its own devices and deprived of leadership, Poland became a convenient field for any actions and surprise attempts that may threaten the USSR. Therefore, the Soviet Government, which has hitherto remained neutral, can no longer remain so in the face of these facts.

Nor can the Soviet Government remain indifferent at a time when brothers of the same blood, Ukrainians and Byelorussians, living on Polish territory, and left to their fate, find themselves without any defence.

In view of this situation, the Soviet Government has issued orders to the Supreme Command of the Red Army for its troops to cross the border and take the lives and property of the people of Western Ukraine and Western Byelorussia under its protection.

At the same time, the Soviet Government intends to make every effort to free the Polish people from the miserable war into which they have been driven by their unwise leaders, and to provide them with the opportunity of existing under peaceful conditions.

Moscow, 17 September [37]

Wacław Grzybowski in conversation with Vladimir Potemkin (First Deputy People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs of the USSR):

None of the arguments used to justify making the treaties worthless pieces of paper stand up to criticism. According to my information, the Head of State and the Government remain on Polish territory…. In any event, the issue of the Government is not important at the moment. The sovereignty of the State exists as long as the soldiers of the regular army are fighting…. What the note says about the situation of minorities is nonsense. All minorities… prove with their deeds, their complete solidarity with Poland in the battle against Germanism. Many times in our conversations you spoke of Slavic solidarity. At the present it is not only Ukrainians and Byelorussians who are fighting at our side against the Germans, but also the Czech and Slovak legions. Where, then, has your Slavic solidarity gone?

Moscow, 17 September [37]

Józef Borowski (a Pole temporarily in Moscow):

It was not until 5 o’clock that Ambassador Grzybowski returned. Just a few minutes later the counsellor was running to the chancellery to dictate a cable. I learned for now that, likely at this very moment, Soviet troops are entering the borders of the Republic of Poland as the aggressor and as Germany’s ally. […]

Around 6 o’clock, there was already movement throughout the embassy. Secret archives were being burned.

Moscow, 17 September [24]

Author: Michał Bronowicki [KARTA]

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki