One of the several classic ‘Polish insurgences’: armed, bloody and lost. Apart from the romantic legend around it, it is distinguished by the fact that the episode lasting a year was unusually effective in unsettling things as they were. After the lost uprising, two paths of development, possible before, were not available to the Poles anymore: building a bourgeoise-based, autonomous monarchy and relatively correct relations with Russia. The trauma of the quashed insurgence and the repressions that followed made several generations of Poles have a preference for uprisings and consider Russia the cruellest of the partitioning powers.

by Wojciech Stanisławski

Let us recall the following: after twenty years of revolutionary and Napoleonic tumult, Europe seemed, under the decisions taken during the Congress of Vienna, to be returning to the rut of anciens régimes. The rigorous adherence to the rules of ‘restauration, legitimisation and balance of powers’ was supposed to scare the spectre of revolution away.

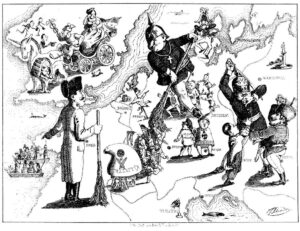

The skimpy quilt of the Viennese order

Was it successful? Yes and no. Over the century between the end of the Congress of Vienna and the outbreak of the First World War and the birth of totalitarianisms, Europe experienced several technological revolutions and profound social transformation. In 1914, the ‘Viennese order’ turned out just an empty shell not supported anymore by any real agreements between monarchs or conservative social groups. At the same time, because of that order Europe saw incomparably fewer wars in the 19th century then before or after: just a few rapid campaigns related to Prussia’s expansion and German unification. Granted, canons did roar, but mostly on Europe’s peripheries (the Balkans, Crimea, Greece, Polish territories or Italy), not at the heart of the continent.

Things looked similarly unclear when it comes to conspiracies. Obviously, a mere four years after the end of the Congress of Vienna the first strictly political murder took place, motivated by opposition against the ‘Viennese order’: on 23 March 1819, the student Karl Sand stabbed the playwright, diplomat and spy August von Kotzebue to death not for any personal reasons but as the latter was a ‘reactionary’. The three decades that followed were a golden age of student plots, the Burschenschaft and Carbonari conspiracies. Sons of the first conspirators caused the Spring of Nations (1848), in Paris a spring without a few barricades was seen as lost, while in the late 19th century, on the one hand, daggers and files became en vogue again (that time around in the hands of anarchists), and on the other – the Second International was able to pull together millions of workers. And yet the foundations of the social order remained unchanged. The entire 19th century was an age of the bourgeoisie: yes, sometimes revolutionary but ‘within the confines of law’.

Did the Polish territories had a chance to develop in that formula? Obviously, they were developing following that logic to a degree, just like the rest of Europe, including the Russian provinces. 19th-century Poles had their share in kerosene distillation as well as setting up weaving mills, banks and socialist parties. Yet they began to bid farewell to the ‘Viennese order’ for good after 1830, following the defeat of the November Uprising and the collapse of the Kingdom of (Congress) Poland.

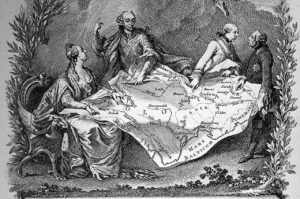

The wreckage after the Commonwealth

Let us recall yet again: the hopes of the generation that sought to prevent the three successive partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian and later Polish Commonwealth (1772, 1793, 1795), and then to invalidate them thanks to cooperation with Napoleon, did not materialise. The partitioning powers (Prussia, Austria and Russia) were on the victors’ side at the Congress of Vienna and no-one could force them to abandon the territories incorporated 20 years previously. Bourbon France saw mainly to pursuing its own interests and having a seat at the negotiating table and Great Britain with foreign secretary Castlereagh sought a balance, which the restitution of the Commonwealth would certainly not have served.

Due to a complicated mix of interests, the willingness to ‘pacify’ Polish elites, quiet rivalries between nominal allies as well as Tsar Alexander I’s idealism, the memory of the Commonwealth as a political project had not yet been completely erased. In the Polish territories incorporated into Prussia (incidentally, the area was slightly slimmed down benefitting Russia), the Grand Duchy of Posen was established, enjoying certain, if ostentatious, autonomy. From the territories incorporated into Austria in 1772–1795, mostly making up a new province called Galicia and Lodomeria, the Free City of Cracow was isolated, also called the Republic of Cracow. It was a miniature polis under the protectorate of the three powers and at their intersection.

From the territories of the formally independent Duchy of Warsaw, created by Napoleon in 1806 and enlarged during his successful campaigns, the Kingdom of Poland was established. Formally independent of Russia, although linked to it by a personal union due to Alexander I, king of Poland and tsar of All-Russia. Outside the Kingdom’s borders remained numerous territories that used to belong to the Commonwealth until 1772. They were now provinces and governorates of the Russian Empire, which was a serious challenge for the local nobility and intellectual elites, whose vast majority felt an emotional bond with old Poland. In the ‘Vienna years’, Alexander was suggesting that a future incorporation of those provinces to the Commonwealth was not excluded. The fact that the promise was not being kept contributed to growing frustration on both sides of the border.

For now, however, in 1815, warm thoughts circulated around the Kingdom, also called Congress Poland in reference to the circumstances of its establishment. Incidentally, the name outlived its reputation – as the term ‘Congress Poland’ denoting the territories between the middle Vistula and the Bug River, populated mostly by Poles, functioned in political geography at least until the outbreak of the First World War, although Russia had long removed all traces of their distinctness or autonomy. At the very start, however, the Kingdom had its own Constitution providing for the Sejm (with elected representatives), an army, a mint and a currency as well as an educational system crowned by the University of Warsaw. Its official language was Polish, larger Russian troops were not allowed to station within the Kingdom and principally the only formal restriction of the state’s sovereignty, apart from a shared monarch, was the absence of its independent foreign policy and the presence of a deputy king (throughout most of Congress Poland’s life, the post was held by a Pole, nevertheless, the former Napoleonic-era officer Józef Zajączek). The monarch had legislative initiative, the right to veto all acts of law passed by the Sejm as well as army commandership. On his behalf, the role was played by the monarch’s brother, Grand Duke Konstantin of the Romanov family: an efficient, brutal, fascinated by Prussian discipline and imposing it on Polish officers at the cost of much humiliation.

Congress Poland, an ersatz of a country

Despite all those limitations, the range of freedoms was still incomparable with what the elites could do in the Grand Duchy of Posen (the Sejm was just an advisory body there, convened more rarely than once a year), in the Republic of Cracow (from the very start, the statelet’s miniature size determined the real, and very modest, ambitions behind it) or in Galicia, back then much Germanised and practically without any representative institutions to speak of. And in the Kingdom? Debates at the Sejm! The opposition! Flourishing sciences, arts, theatre and literature: salons, coteries, several dozen of competing press titles. Education and science meant not only the University of Warsaw, but also the Polytechnical Institute (1820), the Agronomic Institute (1816) and the Society of Friends of Learning!

No wonder that in such circumstances and with such facilities, an unprecedented economic development began in Congress Poland. In the south of the Kingdom, around Dąbrowa Górnicza, iron and zinc metallurgy started to develop as well as coal extraction, while in Łódź cotton workshops boomed. What is more, those were not chaotic, dispersed, individual initiatives by trial and error. Behind them was the Polish Bank, with its extended issuance policy, a vision of constructing hard roads, canals and locks, as well as an urban policy never seen in Polish territories before. Until today, despite 200 years passing and damage wreaked by many wars, the market squares of a few dozen towns which in the Kingdom of Poland advanced to become capitals of provinces or counties sport elegant neoclassical buildings. More often than not, these are the seats of townhalls or courts of old, erected in the 1820s.

One does not know how long that could have lasted. Nicholas I, Alexander I’s younger brother and successor who inherited the throne in the shadow of the Decembrists’ failed coup, could not have been further from his brother’s ideals. Yet Alexander himself began to distance himself from the ‘liberal illusions’ soon after the Congress of Vienna. Particularly when such liberal ideals were being treated seriously: on 15 June 1819, deputy king Józef Zajączek did away with the freedom of the press and imposed preventive censorship, and less than a year later the freedom of assembly was suspended.

The Poles like to plot

And it was just gatherings – particularly ones not allowed by the authorities – that the Poles had a special liking for in that decade. Just a few weeks after the end of the Congress, a conspiracy is founded of émigré officers close to the Napoleonic-era commander Jan Henryk Dąbrowski. In 1817, Warsaw students set up an organisation called Panta Koina, with branches in Breslau and Berlin, and two years later – the Union of Free Poles… Plots, conspiracies and self-education clubs abounded, also outside of big towns: in Svislach, the Scientific Society, the Polish Burschenschaft in Kielce, the Union of Cavaliers of Narcissus in Kalisz … Conspiracy statisticians are able to list more than a hundred larger or smaller clandestine groups established between 1815 and 1830. Many of them operated within a single small town or a secondary school, all of them, if not disbanding themselves, were sooner or later successfully traced by snouts – yet the gene of conspiracy was instilled in the Poles for good back then. Particularly in Congress Poland and territories within the Russian borders, where as many as three-quarters of such groups were found.

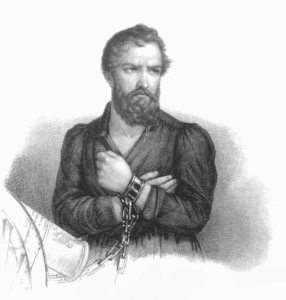

The key of those conspiracies was undoubtedly the Patriotic Society, anchored in freedom-seeking Masonic lodges and established by the active officer Walerian Łukasiński. That was serious now: several hundred plotters, attempts at influencing those of lower rank (non-commissioned officers and soldiers), contacts with the country’s elites and control over garrisons and bastions. The response of the police came immediately. Łukasiński was detained in 1822, and two years later sentenced to public condemnation and nine years of incarceration. Fortunately, he did not know yet that he would spent 44 years in prison, until his death in 1868. Łukasiński became the first hero and ‘martyr’ of the Romantic era.

Łukasiński’s sentence and the emperor’s decision of February 1825 to end with public Sejm proceedings principally ended the ‘honeymoon’ between the society of Congress Poland and Petersburg. Yet for those relations to ultimately deteriorate, a final mutual undermining of trust was needed. That came as further plotters were being looked for among the Poles. After the fall of the conspiracy of the Decembrists, a wide-ranging investigation pointed out to their contacts with members of the Patriotic Society network, not found when Łukasiński had been arrested.

In 1826, more than 120 people were detained, eight of whom charged by the Russian authorities with the gravest of crimes, i.e. state treason. Under the still-in-force constitution, they were put before the Sejm Court of Congress Poland, which, in a bold move ignoring the tsar’s will cleared them off the main charge, sentencing them to imprisonment of just several weeks for participation in illegal societies. The tsar was furious and ordered the kidnapping of the main defendant Col. Seweryn Krzyżanowski, who died in Siberia.

Trust ends and a revolt starts

From that moment on, no mutual trust could be spoken of anymore. The Napoleon-era elites were getting bitter and the young conspired. That time around, those were not experienced military staff but warrant officers and second lieutenants, who on the initiative of Piotr Wysocki established a conspiracy at the School for Infantry Cadets in the autumn of 1828. They did not attain much: they had no press or contacts with the elites and even the management structures were far from perfect. Yet sometimes the point of a conspiracy expires once it has been set up – and certainly that was how it was seen by the secret polices that in the autumn of 1830 found some clues as to the plot of the cadets.

In the meantime, Europe experienced an upheaval. The Holy Alliance could not watch passively at the revolution that broke out in France and Belgium in the late summer of 1830. The fall of the Bourbons would have clearly questioned the decisions of the Congress! Wrathful and quick-tempered, Nicholas I, announces a mobilisation of the Polish and Russian troops on 17 October, a week later the ministries of the Kingdom of Poland receive a secret order to initiate financial restrictions in case of war. On 24 November, Belgium proclaims independence. On that very day, the cadets receive a message about planned arrests.

In the evening of 29 November, a group of a dozen or so people are marching through Warsaw’s Łazienki park towards the Belweder palace, to arrest the army’s commander Grand Duke Konstantin. They fail as he uses a trick to slip through their fingers. He left Warsaw in two days, although he never regained the army, influence or the throne. He died a year later of cholera brought by Russian regiments intervening in Poland.

That was not the only failure on the part of the cadets. Acting without a detailed plan, they let not just Konstantin leave Warsaw but also Russian troops and the prisoner of the state Łukasiński, and handed power over to the elites of Congress Poland, unsure what to do, fearing a confrontation with the power of the Empire.

The rest is already the history of the uprising: heroic, inconsistent and ending with a defeat and emigration of a sizeable part of the military, political and intellectual elite of the Kingdom. Those who on 29 November 1830 were walking through the rustling leaves at Łazienki, less than a year later were withdrawing through forests in the borderland between Congress Poland and the Kingdom of Prussia, only to surrender their arms after crossing the frontier. Yet they triggered something more enduring with their insurgence. Since then up until the First World War, and longer, a large percentage of Poles (although not all!) would be dreaming of an uprising directed against Russia: a victorious one that time around.

Author: Wojciech Stanisławski

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki