Poland reborn after the First World War faced a host of challenges. In particular, the issue of the nature of the constitution provoked a heated debate in the country. The overriding aim of the Act was not only to consolidate the state after the years of partition, but also to create a solid foundation for its development.

by Piotr Abryszeński

During the First World War, the Polish question was raised several times by the partitioning states. The growing losses suffered by Germany and Austria-Hungary on the one hand, and Russia on the other, made it necessary to strengthen their armies with Polish recruits. It seemed crucial to recognise Poles’ aspirations for their own state. This was the idea shared by Germany and Austria-Hungary, who in their proclamation of 5 November 1916 admittedly announced the creation of the Polish Kingdom but assumed it to be dependent and did not specify the shape of its future borders. However, the act caused repercussions on the international arena. Global public opinion took note of the declaration and the Entente states began to demand that Russia issue a similar document. Before this could happen, the throne in Saint Petersburg fell and the Tsarist Empire was plunged into chaos.

Under German and Austro-Hungarian rescripts, the Regency Council was established in Warsaw in October 1917. A year later, at the end of the First World War, it proclaimed the independence of the Kingdom of Poland, and then handed power over to Józef Piłsudski when he returned to Warsaw from a German prison on 10 November 1918. At the same time, local centres of power began to emerge in the country. Irrespective of Piłsudski’s assessment, all political circles agreed in principle that entrusting him with temporary power would calm down public mood. It was in such an atmosphere that the debate on the shape of the Polish political system began.

Governmental committee and parliamentary committee

An important role in the discussion about the future state system was played by Ignacy Paderewski’s Cabinet appointed in January 1919. The Prime Minister was keen to prepare a draft before the Legislative Sejm (Constituent Assembly) started its work. Elected by free and universal suffrage, it met in Warsaw as early as on 10 February 1919, and its initial work took place in very difficult conditions. The borders of the country were still not defined, and there was fighting in many places. Where elections could not be held on the first date due to a lack of formal authority, systematic by-elections were held.

A Constitutional Bureau was set up on behalf of the Paderewski Government. It drew up three preliminary drafts, taking into account various points of view and models used around the world. However, none of them gained the Cabinet’s approval, so already on 25 January 1919 a government committee was set up under the name of the Convention on the Assessment of Constitutional Drafts. It was composed of prominent social and political activists, historians, lawyers and members of clergy from various parts of Poland. The majority were people with conservative and right-wing views. The composition reflected the traditional social elites from before the First World War, while it did not take into account radicalised public mood brought about by the wartime struggle.

The Convention was headed by Michał Bobrzyński, a historian and conservative activist and professor of political law at the Jagiellonian University and Governor of Galicia at the very end of Habsburg rule. Initially, the committee under his direction was to give its opinion on the drafts being drawn up, but its members decided to propose their own solutions to the political system, and so a month later it changed its name to the Convention on the Constitution of the Republic of Poland. The result of intensive, almost four months of work was a document that met with positive opinions of specialists and a certain part of MPs. Inspired by American and French political solutions, the Convention postulated entrusting strong executive power to the president, independent of the bicameral parliament. The authors’ primary goal was to bring about an efficient consolidation of the state, which could only be ensured by an efficient executive. However, the draft was ultimately rejected.

The second actor to join in the constitutional work was the Sejm. On 14 February 1919, a constitutional committee was set up, headed by Władysław Seyda, a member of the right-wing People’s National Union and an excellent lawyer. Alongside him, this body included representatives of other political circles present in Parliament – a total of thirty people. The creation of the second body led to sharp disputes over competences. The members of the Sejm committee stressed that the debate on the form of the constitution should take place exclusively in the Sejm, and not outside it, and therefore demanded that the activity of Bobrzyński’s committee be restricted.

Paderewski’s government appreciated the expertise and experience of the members of the Convention and reserved the right to rely on their opinions. The Sejm, however, treated it as a competitive body. No wonder then that, as a result of political turmoil and disputes without merit over competences, the proposal from Bobrzyński’s committee was rejected. In the meantime, even though the Sejm’s constitutional committee was inaugurated in February 1919, its work did not truly start until September 1920, when the threat from the East had been averted after the victorious Battle of Warsaw.

Piłsudski, Senate and minorities

A temporary solution was adopted until the enactment of the constitution. On 20th February 1919, the Sejm passed a short resolution ‘on entrusting Józef Piłsudski with the further exercise of the office of Chief of State’, which was commonly called the ‘Small Constitution’. It contained just a few points, and regulated political relations in the country, with a parliamentary-cabinet system of government, the supreme power being held by the Sejm. The resolution contained an assignment of a high office to a specific person, which was rare in the world’s legal systems, and that posed a risk of becoming obsolete at the time of Józef Piłsudski’s death.

Compared with the earlier legal status, the Chief of State’s power was limited, though still very extensive. He was entrusted with the execution of Sejm resolutions and the mission to appoint the government in agreement with the Sejm. The Chief of State was also given a parliamentary mandate in military matters, which in the situation of ongoing battles over borders gave him a significant influence over international politics.

Regardless of this, a wide-ranging, nationwide debate began. A special publication was prepared, presenting a summary of the draft constitution proposed by the majority of the Sejm committee, together with amendments and arguments of individual political parties. Both ideological differences and ad hoc interests resulting from calculation became evident. One of the most important points in the debate was the question of the competences of the Head of State and his place in the state system.

An unusual situation arose at that time. Right-wing activists, by nature supporting the postulate of a strong executive power, opted for a weakening of presidential powers in favour of a stronger Sejm. They predicted that Józef Piłsudski would take over this office. On the other hand, the left-wing groupings, traditionally opposed to extending the powers of the executive, this time strove to strengthen them for exactly the same reason. All parties in Poland assumed that the constitution was being drafted with Piłsudski in mind.

That discussion gave rise to another problem, namely the creation of the Senate, the upper chamber of Parliament. This body had a long tradition in Old Poland’s parliamentarism, so it was finally decided to transplant it to reborn Poland. The right-wing parties opted for its establishment, striving to create a mechanism of parliamentary control of sorts. In order to retain the expert nature of the Senate, it was proposed that people who joined the Senate because of another function they held (known as virilists) be added to its composition, which was a reference to the parliamentary traditions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The left consistently demanded the introduction of a unicameral parliament, and in place of the Senate it postulated the a Chamber of Labour, a body focused primarily on the fight for employee rights.

From the point of view of the social system, an important issue was that of national and religious minorities, of which there were many within the still fluid borders of the reborn Second Republic. The right wingers favoured the notion of emphasising the privileged position of the Catholic religion, as the dominant one in the whole society, but eventually the concept proposed by the parliamentary Jewish minority was adopted. The leading role of Catholicism among equal religions was emphasised.

The work on the constitution was turbulent, with all sides putting forward their own ideas, which – combined with the difficult external situation – made it difficult to reach an agreement. In the end, it was the right wing, with its parliamentary majority, that succeeded in pushing through a large proportion of its visions.

Democratic constitution

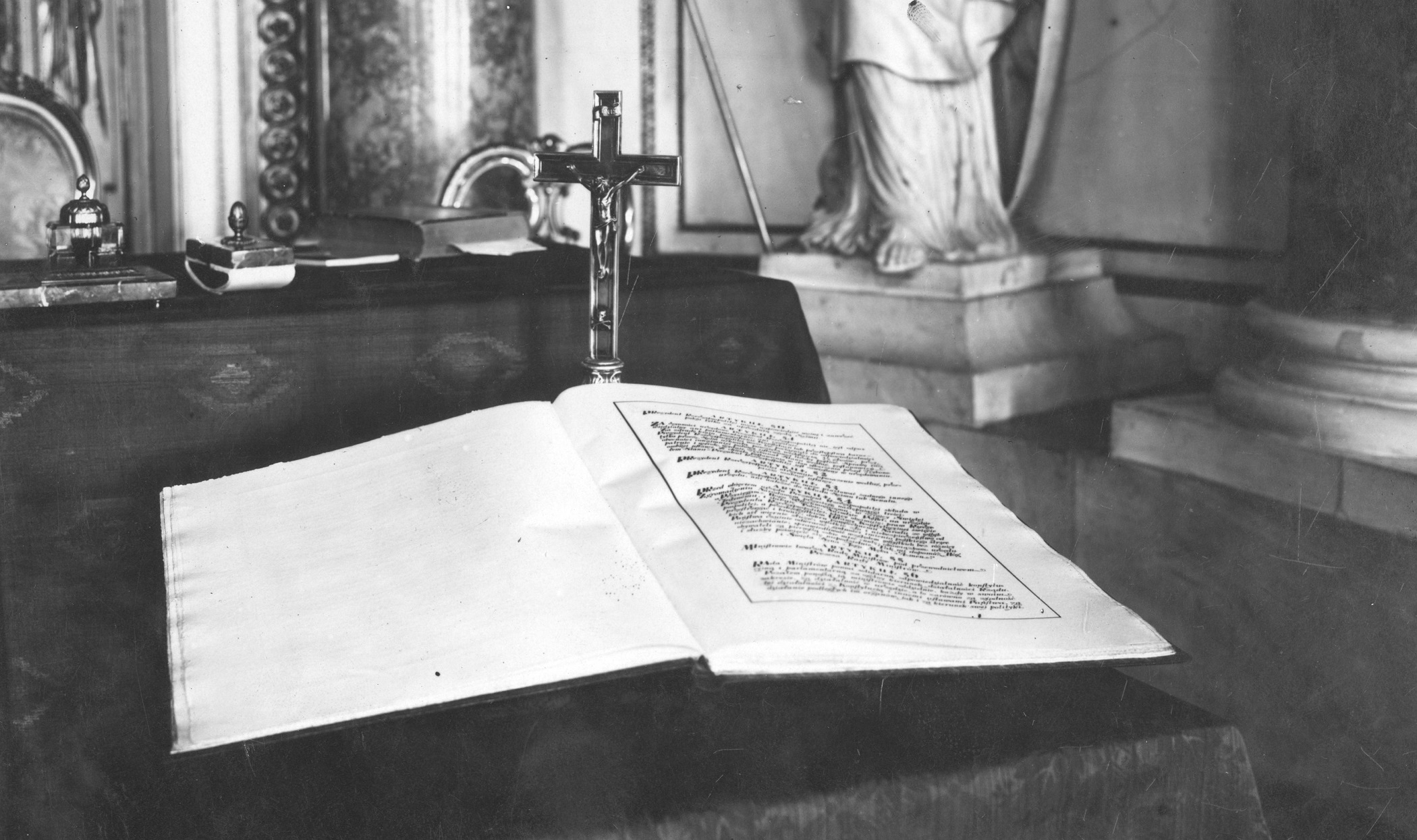

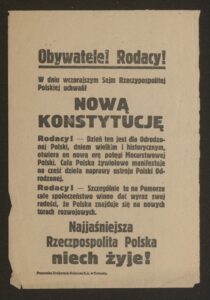

On 17 March 1921, after several readings, almost all the major groupings in the Sejm voted in favour of the constitution. There was euphoria in the streets of Warsaw. In many places, white-and-red national flags appeared, and MPs were feted with exuberant joy.

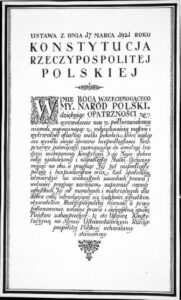

The document established a republican form of state and a mixed parliamentary-cabinet system. It consisted of seven chapters divided into 126 articles. The preamble recalled the long and difficult road to independence:

In the Name of Almighty God! We, the Polish Nation, thanking Providence for liberating us from one and a half centuries of captivity, remembering with gratitude the valour and perseverance of the self-sacrificing struggle of the generations which unceasingly devoted their best efforts to the cause of independence, evoking the splendid tradition of the memorable Constitution of 3 May – seeking to ensure the good of the entire united and sovereign Motherland and wishing to establish Her independent existence, power and safety, as well the social order on the eternal principles of law and liberty, desiring at the same time to ensure the development of all Her moral and material forces for the good of entire renascent humanity, and to securing equality to all citizens of the Republic, and respect, due rights and special protection of labour by the State – we hereby adopt and enact this Constitutional Act at the Legislative Assembly of the Republic of Poland.

The constitution introduced Montesquieu’s tripartite separation of powers and the principle of the sovereignty of the nation, on behalf of which power was to be vested in a bicameral parliament comprising the Sejm and Senate. Executive power was vested in a president elected for seven years by the National Assembly and in the Council of Ministers, while judicial power rested in the hands of independent courts. The nation, as defined by the March Constitution, was a political community of all citizens, regardless of faith or language. This was a clear reference to the category of political nation existing in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and a response to the expectations of national and religious minorities.

The Sejm and Senate played a fundamental role in the state. Members of both chambers were elected in universal, secret, equal, proportional and direct elections, regardless of gender, wealth or nationality. The only requirement was an age limit. The key role of the Sejm meant that the formation of the government depended on the agreement of the parliamentary majority. The Sejm passed laws and the Senate had the right to introduce amendments to them, but the latter could be rejected if an appropriate number of votes were cast. In this system, the President was deprived of important prerogatives. Not only could he not veto laws, but all acts signed by him had to be countersigned by the relevant minister. He could exercise the right of clemency and acted as the country’s representative abroad, but the key role in shaping foreign policy was played by the government.

One of the most important foundations of the system of the Second Republic was territory-bound local government. In this way, parliamentarians sent a clear signal to local communities to become responsibly involved in deciding about their own affairs. This gave rise to a catalogue of broad civil rights guaranteed by the constitution, including the protection of life and the legal defence of property, freedom of speech and independence of the media, freedom of religion, as well as defence of labour rights.

Constitution – and what next?

The final shape of the document was the result of a compromise. As a result, it did not fully satisfy either the right-wing parties, which had a decisive influence on its creation, or the left. Piłsudski was also one of the critics of the constitution. One of his close associates, Stanisław Car, stated years later that

As a matter of fact, the new constitution did not and could not satisfy anyone, as it was not the product of a profound analysis of the real needs of the country, which was emerging painstakingly from a century and a half of captivity in conditions of a world imbalance shaken by the Great War but maturing in a climate of fighting and a party tug of war fuelled by an unfriendly attitude towards the then Head of State.

The climate of dislike for Piłsudski among a considerable part of the constitution’s drafters was a fact. But that was not the only problem they faced. Could reborn Poland become a kingdom? Even before the First World War, monarchies played a dominant role on the political map of Europe. At the end of the 19th century, European states were liberalising their internal relations, parliaments were gaining in importance and legal systems were being democratised, but the position of the monarch seemed unshakeable. Therefore, for a part of the public, a possible revival of the Polish state as a monarchy seemed quite natural, both in relation to the political realities on the continent and to Polish historical tradition. In reality, however, such a solution was not considered in Poland after the First World War. The democratic emancipation of Poles, among whom the people’s hearts and minds were controlled by mass parties: nationalist, popular and socialist, was the decisive reason here.

Historians point out that some of the mechanisms contained in the constitution led to the imminent collapse of the democratic system. The most common accusations include party fragmentation, political polarisation and instability of successive cabinets. However, the systemic solutions contained in the March Constitution can be defended. It was the result of a broad compromise, the primary objective of which was to ensure continuity of the state’s existence in the spheres of defence and foreign policy. The existence of the Sejm and the fact that it was endowed with wide-ranging competences also frequently cooled the heated political disputes, which – though often very sharp – were a natural feature of parliamentary democracy.

At the same time, political theory and practice were at odds. Political diversity, combined with the huge expectations of society as a whole, resulted in an emotional approach to the dispute, which saw the rivalry between the parties as almost a struggle between good and evil. In this context, maintaining a coalition government became increasingly difficult, and it became virtually impossible to continue the political debate. This led to a political breakdown which resulted in Józef Piłsudski’s May coup of 1926, and the adoption a few months later of the ‘August Amendment’ under which the executive gained additional powers.

* * *

The constitution of 17 March 1921 was a commendable testimony to the liberation aspirations of the reborn Polish state and to the desire to confirm its cultural and civilisational links with the West. It was not without reason that the constitution was modelled on that of the French Third Republic. At the same time, however, the March Constitution referred to the systemic traditions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Due to its guarantee of civil liberties and protection of all regardless of national, religious and cultural differences, it was undoubtedly a modern law. Finally, it was proof that, despite conflicting interests and mutually exclusive concepts, Poles were ready to rebuild their statehood after more than 120 years of absence from the map of Europe. This intention proved invariably lasting for the following hundred years.