Forty two years ago, on the night of 12 to 13 December 1981, martial law was imposed in Poland. General Wojciech Jaruzelski – simultaneously Chairman of the Communist party, Prime Minister and Minister of Defence – established a military dictatorship and entered the final confrontation with the ten-million-strong trade union, ‘Solidarity’.

by Tomasz Kozłowski

Preparations for martial law were carried out in strict secrecy. Gen. Jaruzelski and his acolytes were hoping that the rapid implementation of the operation would have a highly chilling effect – ‘Solidarity’ and society were to be paralysed, deprived of the will to defend themselves, and overwhelmed by the presence of the army. All forces were thrown into the streets: 80,000 soldiers and over 60,000 militiamen and secret policemen were involved in the operation. ‘Solidarity’ was taken by surprise. As Władysław Frasyniuk, one of the union’s most important leaders, explained: ‘Nobody counted on the fact that this supposedly weak power would nevertheless prove strong enough to throw militiamen and soldiers (our work colleagues, neighbours from the housing estate) at us. We were more afraid of external [Soviet – author’s note] intervention.’

Most of the Polish soldiers were not professionals, but came from conscription – these young people were not in favour of confrontation, but had to follow orders. One of them recalled: ‘I tried not to look at people. I was ashamed. I walked and pretended that I was not from this town. People knew that I had to do it in some way, and that I was sorry about this. I think they felt a bit sorry for us.’ Mobilising soldiers and bringing tanks onto the streets was intended to have an intimidating effect. In most cases, however, the army was not sent to break up demonstrations or catch oppositionists – this was done by secret police officers and militiamen.

A wall riddled with bullets

The authorities succeeded in achieving the desired effect, the social resistance was small in relation to what had been expected. However, there were factories that became bastions of resistance. Workers used passive protest tactics in them: they fortified themselves in their workplaces and went on strike there. The militia was prepared for such a development. One ‘Solidarity’ leader recalled: ‘The pacification techniques were always similar. Under the cover of tanks that rammed the gates or walls, the Motorised Reserves of the Citizens’ Militia [militia units specialised in suppressing protests –author’s note] broke in at night, using rockets to illuminate the area. Closed doors were smashed with crowbars or axes, people were driven out. Batons and gas grenades were often used. All the detainees were lined up in a square, and those whose names featured on previously prepared lists were selected.’

During such operations, the militiamen attempted to avoid using live ammunition, but there were some tragic exceptions. During the pacification of a strike at the Wujek coalmine, a special unit sent to the site opened fire, and the officers killed nine and wounded others. The use of such brutal measures intimidated workers in many other plants. The mood gradually deteriorated, resistance became weaker, and a sense of hopelessness and apathy emerged. The last occupational strike – led underground by 1,200 miners from the Piast mine – ended on 28 December 1981.

At the same time, arrests of Solidarity leaders and democratic opposition activists were made all over the country. During the first hours of martial law they were unsure of what fate awaited them. Many feared that General Jaruzelski – following the path of Latin American dictators – would decide to definitively solve the problem of the political opponents. Jacek Kuroń, one of the leading activists of the Workers’ Defence Committee, recalled: ‘They brought me to some free-standing building in a suburb. They led me down the stairs to the cellar. The basement was covered with sand and the wall I was walking towards was riddled with bullets. Militiamen in military uniforms were standing against two other walls, with submachine guns slung over their shoulders (…) Ah, this is it. Already? What a pity.’ Kuroń was not shot, however, but interned. Just like almost 10,000 other people – led by ‘Solidarity’s’ chairman, Lech Wałęsa – considered a threat by the authorities.

The legal basis for the internment was questionable, but nobody cared. The judicial system was de facto switched to a wartime mode of operation. The role it played is still controversial today – many judges did not show independence, and resigned themselves to the role of a tool in the hands of the communist authorities. Bogdan Dzięcioł, president of the Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court, expressed a symbolic opinion, when, before an important political trial, he assured the party leadership that ‘we have a dedicated panel of judges, who guarantee proper preparation of the case, and ensure that the correct verdicts will be delivered relatively quickly’.

Two years for a whistle

During martial law, the courts sentenced over 3,500 people to prison. Some of the sentences were extremely disproportionate to the acts committed. There is a story of an engine driver who started a train whistle for 60 seconds as a symbol of opposition to martial law, and was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment. Ewa Kubasiewicz, who took part in a peaceful strike at the Gdynia Maritime University, was sentenced to ten years. Colleges of misdemeanours, which could punish, inter alia, violations of martial law, slapped penalties, mainly fines, against over 200,000 people.

With the introduction of martial law, ‘Solidarity’s’ activity was suspended, while its formal liquidation was postponed for several months. For many of its members, this point in time marked the end of their involvement in trade union activity. Aleksander Hall, one of the leading oppositionists, assessed: ‘It turned out that, if the authorities struck quickly and decisively, we were unable to counterattack or even shield ourselves from the blow. Our model of resistance did not survive the test of time.’ The few Solidarity leaders who avoided arrest, went into hiding and tried to organise underground activity. They built secret structures, published illegal press, and organised demonstrations. Such activity, however, involved only a few people, while most sought symbolic ways in which to manifest their opposition. One new tradition became to display candles in windows. ‘We would light a “Solidarity” candle on the window sill, as called for by the Union leaders in hiding,’ recalled one witness, ‘Candles were also lit in the windows of other blocks on the estate. Although maybe not as many as we would have liked.’

Life goes on

The majority of society did not think about organised resistance, but about adapting to the new situation. A curfew was imposed all over the country – people were forbidden to leave their homes between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. It was forbidden to move freely around the country, and the borders were closed. But life went on. A resident of one of the big cities recalled: ‘I am standing with my child on a hill in the park, tanks are passing nearby, patrols are walking around. And suddenly I see a woman walking. She has a lampshade in her hand. Just bought, wrapped in paper. And this is what I could not understand. Martial law, and the most important thing for her was to buy a lampshade.’

After the first strike, the suppression of protests and the relative stabilisation of the situation, the authorities proceeded to the next stages of the operation. ‘Solidarity’ was not just a trade union for workers – it encompassed various professional groups, and even institutions regarded as pillars of communist power. Judges, prosecutors, militiamen and journalists, among others, formed their own organisations. All these groups were subject to verification – people who did not support the policy of the authorities were dismissed from work.

Many rebellious judges were dismissed from their positions, but today it is difficult to reconstruct a complete picture of this purge, which also included cases of ‘voluntary resignations’ and demotions. Special commissions were established to verify the journalistic community, which gave a negative opinion of about 10% of the employees. At the state press concern Prasa-Książka-Ruch, over 300 people lost their jobs and 60 editors-in-chief were dismissed. More than 230 journalists were dismissed from the Radio and Television Committee. There were also purges in general and higher education.

Ordinary workers were not spared either. Many factories – particularly those in the mining, communications and telecommunications sectors – were militarised. People working there were subjected to severe penalties, not only for attempts to organise protests, but also for absence from work. By August 1982, over 55,000 people had been fired, often collectively. 178 workers were sacked from the Świdnik Communication Equipment Factory in retaliation for organising a 15-minute strike.

Many people inconvenient to the authorities were forced to emigrate. Gen. Jaruzelski was inspired by the history of Cuban Marielitos. In 1980, Fidel Castro allowed thousands of people – including released prisoners and residents of psychiatric institutions – to emigrate to the USA. Jaruzelski explained to the Soviet ‘comrades’: ‘Let a few thousand escape [from Poland – author’s note], as Fidel had allowed, then it would be much easier for us.’ Between 1982 and 1988 – often as a result of pressure and harassment – ca. 1,100 former internees and their families emigrated from the country. This was only part of the wave. The authorities gradually opened the borders – it is estimated that, in the 1980s, up to a million Poles could have left the country irretrievably. The migrants were motivated not only by political but also economic reasons. They saw no prospects for themselves in Poland. In this way – through repression, broken careers, forced emigration – the authorities dealt a heavy blow to the nascent civil society.

Praise for Comrade Brezhnev

The destruction of ‘Solidarity’ was greeted with relief by the Kremlin. Jaruzelski boasted to his associates: ‘I received a phone call from Comrade Brezhnev, who referred to us in a friendly tone, and stated that we had successfully joined the fight against counter-revolution. These were difficult decisions, but the right ones. My speech was highly appreciated. Brezhnev assured us that we could count on economic assistance.’ That last sentence was crucial. The economy was on the verge of collapse and, in February 1982, food price rises of up to 250 percent were introduced. At that time, 92 percent of the population assessed the economic situation as bad. Nobody counted on improvement. And rightly so – attempts at economic reform failed in the following years.

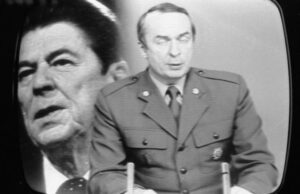

The imposition of martial law was criticised by Western countries. In the USA, 30 January 1982 was declared a Day of Solidarity with Poland. In a special proclamation of 20 January 1982, President Ronald Reagan explained: ‘Despite these peaceful efforts on the part of Solidarity, a brutal wave of repression has descended on Poland. The imposition of martial law has stripped away all vestiges of newborn freedom. Authorities have resorted to arbitrary detentions, and the use of force, resulting in violence and loss of life; the free flow of people, ideas and information have been suppressed; the human rights clock in Poland has been turned back more than 30 years. The target of this repression is the Solidarity Movement but in attacking Solidarity its enemies attack an entire people. Ten million of Poland’s thirty-six million citizens are members of Solidarity. Taken together with their families, they account for the overwhelming majority of the Polish nation. By persecuting Solidarity, the Polish military government wages war against its own people.’

Words of condemnation were followed by retaliation. The White House introduced sanctions against the Polish People’s Republic and the USSR. Imposed under pressure from the Kremlin, martial law became one of the impulses that led to a new strategy of confrontation with communism. The Soviet Union was embargoed on modern technologies, numerous trade barriers were created, and the noose of debt was tightened around the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. The Central Intelligence Agency supported ‘Solidarity’ in Poland and its offices abroad – some 20 million dollars were allocated for this purpose. It was thanks to these funds, among others – apart from the support of international trade union organisations – that Solidarity was able to operate illegally, underground, throughout the 1980s.

Martial law was lifted in July 1983. Jaruzelski achieved his goal of breaking up ‘Solidarity’, but nothing more. Under the cover of troops, he failed to effectively reform the economy – the country was plunged into economic and social stagnation for many years. The price of martial law was merely buying time. When, in 1988, the authorities again saw the spectre of mass protests, Jaruzelski – with the blessing of Mikhail Gorbachev – launched political negotiations with the leaders of the underground ‘Solidarity’ movement, the very people he had ordered to lock up a few years prior. These talks resulted in the partially free elections of 1989, which became a great success for ‘Solidarity’. Tadeusz Mazowiecki, a close associate of Lech Wałęsa, became Prime Minister. Wałęsa himself became President in 1990.

The cost of this peaceful revolution was the impunity of the old regime’s politicians, including Jaruzelski himself and his trusted Minister of the Interior, General Kiszczak. Their trials dragged on for years, without them ever actually being held criminally responsible for the imposition of martial law.

Author: Tomasz Kozłowski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin