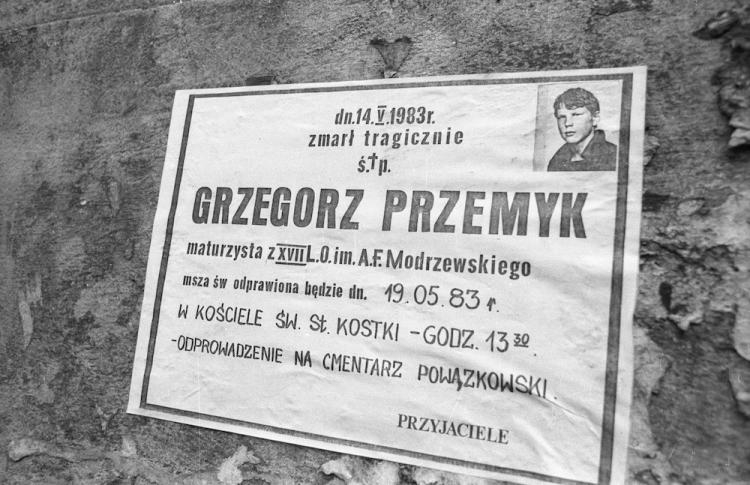

In May 1983, militiamen beat Grzegorz Przemyk to death; a young boy celebrating the successful completion of his school exams. The entire state apparatus was involved in covering up the case, and ensuring impunity for the murderers. This tragic story shows how defenceless the individual was against the system of oppression.

by Tomasz Kozłowski

Grzegorz Przemyk who, on 12 May 1983, celebrated his graduation from secondary school, was stopped by a police patrol and taken to the police station with a friend. What was initially a routine detention turned into a nightmare. The militiamen decided that Przemyk was too tough and needs to be taught a lesson. Three officers beat him in the stomach – so as not to leave any traces.

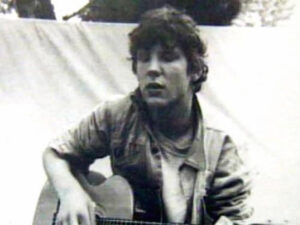

Przemyk was taken from the police station by ambulance, but the beaten boy wandered from one doctor to another for a long time. When he was finally taken to a surgeon, it turned out that his internal injuries were so extensive that even an immediate operation could not save him. Przemyk died. The news of the tragedy had soon spread all around Warsaw. The slain boy’s mother, Barbara Sadowska, was a respected poet who supported the democratic opposition. A few days before the incident, she herself had been beaten up by a unit of plain-clothed militiamen who were carrying out ‘dirty work’ on the orders of the management of the Ministry of the Interior. It was suspected that Przemyk’s arrest and torture were in fact revenge, and an attempt to intimidate his mother.

War losses

In reality, however, it was lawlessness on the part of the militiamen. Such a political murder was not to anyone’s liking. At one secret session, the Minister of the Interior, General Czesław Kiszczak, cynically stated that, had an execution had been planned, experts would have been sent to carry out this task. Meanwhile, the case of Przemyk’s murder began to spread in ever-widening circles – foreign correspondents wrote and spoke about it.

The authorities were afraid of the consequences. They did not want to allow for a public image disaster, but they also did not intend to punish the guilty. Kiszczak explained that the ‘officers who, participating in the struggle to maintain order, were forced to abuse power and are accused for that reason, must be unconditionally and consistently defended. Incidents of this type must be treated as action during a war.’

At that time, Poland was under martial law, which was introduced in order to break up the ‘Solidarity’ trade union and the democratic opposition. The apparatus of coercion (the militia, the Security Service [Polish acronym ‘SB’] and the army) and the judiciary (the military and civilian judiciary and prosecutors) were pacification tools for the Polish society – the authorities required them to turn on their fellow citizens. Nobody spoke about this, but it was obvious that the officers were given permission to use violence. Unpunished militiamen increasingly vented their aggression.

Beaten a few days prior to his 19th birthday, Przemyk was not the first or the last victim of such government policy. Less than a year earlier, Emil Barchański had been killed in unexplained circumstances just one day before his 17th birthday. There were more such cases. In Toruń, militiamen on patrol beat Jacek Osmański to death, a militiaman himself, who had gone to a hard rock concert on that day wearing civilian clothes. There were dozens of innocent victims during the martial law.

The militiamen’s superiors had no intention of admitting their guilt this time either. On the contrary, they began to fuel the spiral of violence. Przemyk’s secondary school friends were intimidated. One of the students who organised the demonstrations – Wojciech Cejrowski – today a well-known publicist and author of films and travel books – was detained, beaten, and finally had fingers of both hands put out of joint. He took his final exams with his hands immobilised. However, the case of Przemyk’s beating was too high-profile to be swept under the carpet. The news of the militia’s bestiality – in spite of the attempts by authorities to silence it – became public via western radio stations, including Radio Free Europe.

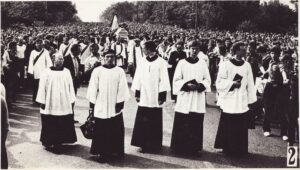

Visiting Poland in late June 1983, Pope John Paul II personally met with the mother of the murdered boy. During one of his public meetings, someone drew his attention to her saying: ‘Father, Father, This is Basia (…) This is Basia Sadowska, whose son they murdered.’ The Pope ‘pressed her to his chest and, in a very cordial way, asked her about Grześ – she felt it was a consolation,’ recalled Wiktor Woroszylski. The photograph of Sadowska cuddled up against John Paul II found its way into foreign newspapers – the French Le Figaro published it. Public opposition to martial law, the breaking up of ‘Solidarity’, and the brutality and impunity of the police, focused on this senseless murder. The authorities were frightened.

Harassment

In the following months, hundreds of militiamen and Security Service officers took part in wide-ranging actions aimed at obstructing the investigation. A propaganda campaign was launched, and psychologists were consulted on strategies about how to improve the image of the militia. However, the greatest efforts were made to slander all witnesses, friends, family, as well as Przemyk himself. Entire teams questioned people, and scoured files and archives, in search of any blemishes on their biographies. Key people were placed under round-the-clock surveillance, wiretaps were installed, and people cooperating with the secret police were placed among them. ‘Gossip’ leaked to the media controlled by the authorities – true and false information provided by the SB about mental and health problems, past sins and life vicissitudes of witnesses testifying against militiamen. All this was to discredit them in the eyes of the public opinion, but also to create psychological pressure that was difficult to withstand.

Such measures had been present in the arsenal of the secret police for many years, and were used mainly against people who could not be arrested, kidnapped, or beaten, i.e. well-known opposition activists, writers or actors. The SB referred to such operations as harassment. They were not written about in official reports, and any traces left in documentation were erased. In one of few surviving documents, one can find information about people connected with Barbara Sadowska. The SB officers wrote about Maja Komorowska, an actress and friend of Przemyk’s mother: ‘During her absence from home, the lock was immobilised. The tyres of her car were permanently damaged. Harassing phone calls were made late at night.’

The same document contains information on how attempts were made to devalue Władyslaw Siła-Nowicki, a lawyer working for Sadowska: ‘There is widespread information that his procrastination in the defence [in one of the criminal cases] (…) was deliberate and was intended to cause the Military Court to consider the case, and thus to impose harsher punishments.’ Threatening anonymous letters were also sent to him. Accusations were further made against the other lawyer working for Sadowska, which effectively prevented him from participating in the trial of Przemyk’s killers.

In order to break or intimidate their victims, officers often targeted their loved ones. Such measures were used against one of the paramedics who drove Przemyk in the ambulance. First his mother-in-law was made redundant from her job. Then his brother was beaten by unknown perpetrators. Finally, the militiamen began scaring him with visions of his son dying in an accident: ‘I remember this interrogation,’ he recalled in a conversation with Cezary Łazarewicz, ‘Three civilians unknown to me enter. They are talking to one another so loudly that I can overhear them. They are talking about how Piotr Bartoszcze, a “Solidarity” activist who they had found dead in a ditch, and about whom the whole of Poland rumoured that the SB had finished him off, had drowned. They are also saying that it was no accident. They are joking about his death, laughing out loud. Suddenly, one of them asks: “Does Peter return home from school by himself? It’s so dangerous. There are so many accidents on the roads today”: They knew his name and which school he went to. I felt numb. They had sensed my weakness. They had hit the most sensitive spot. I returned to my cell and thought of nothing but Peter. Is he safe? Will no one hurt him? How to protect him?’

A scapegoat

The cover-ups, intimidation of witnesses and propaganda campaign would not have had any significant effect had the regime not found a scapegoat to blame for Przemyk’s murder. The chosen ones were employees of the ambulance service. The tracking, harassment, and arrests began. They were looking for people who could give false testimonies incriminating the nurses or doctors, and they were trying to turn the ambulance workers against one another.

Kiszczak pressed: ‘There is to be only one version of the investigation – that of the paramedics.’ Eventually, it was decided that two emergency medical technicians would be blamed for the beating. They were arrested and interrogated. A team of eight investigators was set up to take the detainees to the brink of physical and psychological exhaustion. The aim was to obtain confessions – the EMTs were to make self-incriminations or incriminate one another. They were put under such pressure that one of them attempted suicide. The officer questioning him later explained with feigned compassion: ‘Michael, I know you want to leave this world. But first you have to take the blame for those guys from the militia who are involved in this.’ The paramedics did not stand a chance – they were ready to say anything just to end the nightmare.

Their coerced testimony did not convince even the prosecutor in charge of the case. Pressured by his superiors, he found himself in a no-win situation – he would rather resign than confirm the false testimony with his name. In the end, Kiszczak himself had the greatest influence on the content of the indictment. Charges were brought against both militiamen and paramedics. While the former were accused of simple beatings, which could be punished with up to three years’ imprisonment, the ambulance workers were threatened with many years’ imprisonment for aggravated battery. In the end, the court sentenced them to more than two years in prison. The policemen were acquitted.

In 1985, General Wojciech Jaruzelski praised the Minister of the Interior during a meeting of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party: ‘Comrades, had it not been for Kiszczak’s stubbornness, iron stubbornness, (…) it is not known how this would have ended. But he was the one who led to the discovery, to the evidence that, in spite of everything, this could not be blamed on the militiamen. Today, this is a relief for us: they are talking about Przemyk, but they have to speak in hushed tones, because the television showed it, everything was documented and justified.’

The consequences

Did Jaruzelski really believe this? Doubtful. Even Mieczysław Rakowski, one of his close associates, wrote in his diary: ‘I observed the Przemyk case from the first moment. It was known that it was militiamen who beat him, but they were not the ones sentenced. Jaruzelski always said that the truth must be uncovered in this case. But what did he mean by that?’ The atmosphere of impunity soon led to a similar tragedy – SB officers murdered Father Jerzy Popiełuszko.

Popiełuszko was a clergyman associated with the underground ‘Solidarity’ movement. It was he who had buried Grzegorz Przemyk, and comforted his mother. Ligia Urniaż-Grabowska recalled that he was one of those people who had brought Barbara Sadowska solace: ‘He came to Baśka and announced that he would personally see Grzesiek off. He promised to take care of everyone else, too. Then he sat down in an armchair and hugged her. And so they sat embraced in silence. It lasted a very long time. Finally, he made the sign of the cross on her forehead and left. Such gestures allowed her to survive.’

The priest was murdered by SB officers several months after Przemyk’s murder. The authorities could not cover up this crime, so they decided to punish the guilty in a show trial. Known as the Toruń trial, it was conducted at a superspeed pace, and the SB officers were sentenced to prison terms. To this day, it remains uncertain who ordered the murder of Father Popiełuszko, and who was politically responsible for this crime. It would seem that Jaruzelski and Kiszczak should have been blamed. However, this was not the case. Thanks to their political and socio-technical efforts, both generals staved off suspicions of being the perpetrators.

Sowing rumours, insinuations, deliberate indiscretions and lies, led to the political burdening of other members of the communist authorities. The truth was most likely that, in their feeling of impunity, the SB men overstepped the mark. Rakowski noted in his diary, in the context of the murders of Popiełuszko and Przemyk: ‘What happened is a consequence of the impunity the Ministry of the Interior had enjoyed so far.’ The blame for this lay with Kiszczak, who evaded responsibility this time too.

The issue of the obstruction of justice in the Przemyk case did not come to light until 1990, when the newly appointed general prosecutor found documents exposing Kiszczak’s role in the whole affair. As a result, ‘Solidarity’s’ Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki dismissed him from his post. The investigation was reopened, and the trial resumed – one of the militiamen was convicted in the lower instances, but the crime was ultimately time-barred. Przemyk’s murder left a permanent mark also on his friends, as well as on the accused employees of the ambulance service, whose lives are marked by trauma to this day.