“A great thing is being created right before our eyes. Thousands of people sacrifice the work of their minds and muscles for the greatness of their homeland. We must not remain indifferent. And we also have to contribute to the Central Industrial District with our heart and our generosity” – thus stated the authors of an information booklet issued in 1938. It advertised the largest Polish investment project at the time – the Central Industrial District.

by Andrzej Zawistowski

When the industrial revolution reached Central Europe in the 19th century, Poland as a state could not be found on any map of the continent. Its land, divided at the end of the 18th century between Russia, Austria and Prussia, had been incorporated into various economic organisms. After 1918, a single entity needed to be created out of these three parts – a Polish economic organism. It was not easy. Sometimes the obstacles were quite mundane – the composite parts used different standards of measurement, weight and traffic laws. However, sometimes there were fundamental problems, such as changes in the borders, lost sales in the countries of former invaders, and the confinement of major industrial centers within the borders of the new state which were particularly important from the point of view of defense. A large part of Polish industry was located in Upper Silesia – that is, right on the German border. If there was an armed conflict, these mines, steel mills or factories would be on the front line. Even more important, however, this reborn Poland needed a new and modern industrial sector, the development of which would lead to the modernization of the country. Giving jobs to the millions of people who were waiting in the country’s overcrowded villages.

Safety triangle

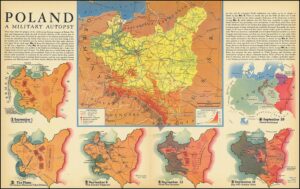

In 1921, because of the above mentioned conditions, the question of the development of the Polish defense industry in the so-called safety triangle came up. This area was basically marked by the bifurcation of two rivers: the Vistula and the San, although the exact boundaries of this territory changed frequently. When it lost the shape of a triangle, other names appeared, such as “security area” or “central area”. Of course it is not only due to the natural shape of the area that it is referred to as the “safety triangle”. About 200 km separated it from the border with Germany, and over 300 km from the Soviet Union. It was much closer to Czechoslovakia in the South, with which the Second Polish Republic had quite cool relations, and some natural protection was provided by the Carpathian Mountains. However, these defensive calculations did not take into account revolutionary changes in the way wars were fought. One hundred kilometer distances may have been a significant obstacle for infantry or cavalry. For dynamically developing motorized troops, especially aviation, this was not such an obstacle.

Work on the “safety triangle” took years. At that time, however, only a few ordnance factories were expanded. It wasn’t until March 1928, that entrepreneurs investing in the triangle were released from certain taxes and fees in order to encourage private investors. Soon after, the construction of the State Nitrogen Compound Factory in Mościce began, which turned out to be the largest state industrial investment of the Second Polish Republic. Part of its production was to serve the army.

However, ambitious plans did not bring about expected results. First, a part of the military distanced themselves from the “central district” idea, then the great crisis of the late 1920s came. Poland found itself among the countries most affected by the economic downturn and dreams of large investments had to wait.

The concept of Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski

At the same time, however, it was the crisis that gave rise to the concept of the Central Industrial District. In order for the country to overcome the crisis, it required investments that would create new jobs. This was understood by Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of the Treasury Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski (former director of the above mentioned plant in Mościce). He proposed the implementation of a four-year investment plan, whose most important point was the establishment of the Central Industrial District. At the same time, the army worked on its own six-year plan to modernize and develop the armed forces. In both of these ideas, the “safety triangle” would prove to be crucial.

In February 1937, Kwiatkowski first publicly presented the concept of the Central Industrial District. The concept envisioned that this area would become an economic success, a real source of modernity and prosperity. After several months of consultations, it was decided that the Central Industrial District would be established in an area covering 15 percent of Poland, including 46 districts that belonged to regions of Kielce, Kraków, Lublin and Lwów. In the future, most of the Central Industrial District area was to be integrated as part of one region with the capital in Sandomierz. In this way, the historic city would return to its status as capital of the region. It had been so for over 400 years, only losing its position following the fall of Poland in 1795.

The area of the future Central Industrial District was inhabited by almost 6 million inhabitants, 18 percent of the population of the Second Polish Republic. Most of them lived in the countryside – only less than a million lived in the area’s 94 cities and towns. It was estimated that of these 6 million people, up to 700,000 were free laborers and they were in need of a job. If they found employment, they would also become the recipients of the agricultural production, which would enrich the populace in the countryside.

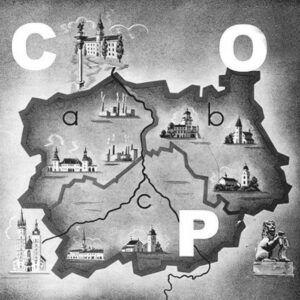

A, B, C.

The Central Industrial District was to consist of three regions. Region A, located around Kielce and Radom, had a strong focus on raw materials. Iron and copper ore were both extracted here. But this area also included the historic Old Polish Industrial Area. There were already ordnance factories in Skarżysko, Starachowice, Pionki, Kielce, Radom and other places. Some of them were expanded or modernized in the 1920s, when the concept of “safety triangle” was born. Already in 1936, a semi-automatic FB Vis pistol was produced in Radom – one of the best Polish weapons. The existing plants were incorporated into the Central Industrial District, some had even been expanded.

Lublin became the capital of region B. This area – due to its fertile soil – would supply the Central Industrial District with food. This does not mean that it was free of any industrial investment. It was necessary to create jobs outside overcrowded agriculture. Ordnance factories were to be built in Kraśnik and Jawidz, and TNT was to be produced in Krasnystaw. Lublin was to become the centre of aviation and automobile production.

The heart of the Central Industrial District was to be region C, located within the safety triangle. The village of Pławo was situated there and became the most important industrial centre of the entire district, eventually even becoming part of the new city of Stalowa Wola [Steel Will]. The name had its direct origin in the words of the then-Minister of Military Affairs, General Tadeusz Kasprzycki, who spoke about the establishment of the Central Industrial District as “the steel will of the Polish nation to break through and distinguish itself as a modern country”. The Southern Plants were established in Stalowa Wola. They included an ironworks and steel mill, and in following years an aluminum smelter. Mielec was designated as the seat of the Polish Aircraft Works. In Rzeszów, among others, a aircraft engine factory would be established. Dębica was meant to be the future location of chemical plants, the Rubber Factory (i.e. tires) and a metalworking factory. Gunpowder, ammunition and weapon factories would also be built in several places.

Why was the defense industry the primary focus of the Central Industrial District? The answer was simple. War was coming and Europe was beginning to arm itself. The Polish Army also needed modern weapons, and the state engine production was not able to meet these needs. Imports from foreign factories required a wait of many years. Whoever wanted to get weapons quickly needed to build ordnance factories. This does not mean that there were no plants with a different production profile in the Central Industrial District. However, the scale of this kind of investment was smaller than that of the defense industry.

Hydroelectric power plants in Rożnów (where investment had started before 1936) and Myszkowice, Solina, Czchów and Lesko were planned for the needs of the developed industry and the population living there. At the same time, a system of gas pipelines transmitting natural gas from nearby deposits was created. This solution was of strategic importance – in the event of war with Germany, one did not have to count on coal mined in Upper Silesia. However, traditional coal power plants were also created – primarily for the needs of specific plants. This was to be complemented by investments in rail and road infrastructure. Obviously, apartments for employees in the cities of the District were taken into consideration. The number of inhabitants of Sandomierz would increase from 10,000 to 100,000.

Investment in motion

According to Kwiatkowski’s ambitious plans, the Central Industrial District was to be established by 30 June 1940. State investments were to absorb up to 1.8 billion Zloty. However, attempts were also made to encourage private entrepreneurs to invest – they were offered numerous concessions and facilities. The response, though, was rather cautious and modest.

However, works in the District began and government propaganda developed along with it. Journalists and writers were writing about the Central Industrial District, including Maria Dąbrowska and Melchior Wańkowicz. His report from the construction site of the Southern Works ended: “These boys, as well as the whole country, can now work equally, in fair conditions. However, they would need as much as the others did, necessary in every age and in all circumstances – strong will,[and a] willingness to pursue their aims. Therefore, it was a fortunate idea that the place where steel will be produced, established in the middle of the woods, received the name – Stalowa Wola [Steel Will]. It is a testimony of its production and encouragement for those who live there.” Wańkowicz decided to take a risky stylistic move, taking into account the attitude of most Poles to the USSR: and called Stalowa Wola the “Polish Magnitogorsk” [was an industrial city in the USSR].

The comparison was accurate though. In the 1930s, a huge steel mill was built ‘from scratch’ in Magnitogorsk (but what Wańkowicz did not foresee was that this effort was the labor of political prisoners). It was one of the flagship investments of the first Stalinist five-year-old plan that the Soviet state boasted about around the world.

Despite the fact that, in June 1939, the four-year plan of Prime Minister Kwiatkowski was pronounced a success, the Central Industrial District was not yet finished. Plants whose construction was completed (and this was a small part of the planned amount), employed approximately 100,000 people, although there were far more people looking for work there. However, arms production started off slowly.

Until the outbreak of the Second World War, 10 new factories began operating at the Central Industrial District: South Plant in Stalowa Wola, Fabryka Obrabiarek H. Cegielski in Rzeszów [a machine tool factory], Fabryka Gum Jezdnych “Stomil” in Dębica [a tire factory], Wytwórnia Magnezu Metalicznego w Bliżynie [metallic magnesium], Fabryka Kauczuku Syntetycznego w Dębica [natural rubber], PZL Wytwórnia Silników nr 2 in Rzeszów [engines], Państwowa Fabryka Amunicji nr 2 in Kraśnik [ammunition], PZL Wytwórnia Płatowców nr 2 in Mielec [airframes], Wytwórnia Amunicji nr 3 in Majdanie-Dębie [ammunition], Lignoza SA in Pustkowie near Dębica.

After the Third Reich occupied the Central Industrial District in 1939, Germany began to dismantle and remove the factory equipment. However, when they attacked the USSR in June 1941, the former factories under German management had to take up production for units fighting on the Eastern Front. In 1944, the PZL Engine Factory in Rzeszów employed over four times more employees than in 1939. Soon, however, the Third Reich began dismantling the factories again as Red Army troops approached from the east. After the war, the Communist authorities ceased promoting the development of the Central Industrial District as a project created in the Second Polish Republic. The industrialized area created in the Second Polish Republic was not abandoned though. What’s more, many investments planned in the 1930s were also eventually completed.

The Central Industrial District next to the harbor of Gdynia was the largest investment of the Second Polish Republic and a symbol of its economic development. Undoubtedly, this investment ended the weak Polish economic policy that had lasted for years. Most factories had become important industrial centers. Of the ten factories that were opened up to September 1939, eight – in various forms – still operate today. Some of them are even in the hands of large global companies – from Goodyear to Lockheed Martin.

Author: Andrzej Zawistowski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin