The 1989 revolution created an opportunity for the resurgence of a democratic state in Poland. That is why the elections for local authorities that were held on 27 May 1990 were so important. It was a first step on the road to rebuilding democracy on a local level after nearly half a century of Communist rule.

by Tomasz Kozłowski

The Second World War and the occupation of Poland by German troops put an end to local governments. It could not be rebuilt after the war, because the Communist authorities intended to introduce an extremely strict control over social issues. In 1950, a multi-level system was introduced, and included the so-called national councils. In fact, they were not only a local form of state power, they also remained subordinated to the ruling Communist party – the Polish United Workers’ Party. For several decades after the war, nobody remembered what local government and grassroots democracy were about.

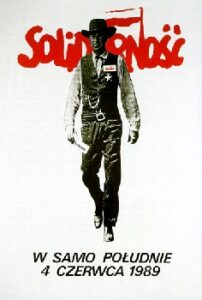

The idea of local government returned to the public debate in the early eighties, thanks to the Solidarity revolution. In 1980, after huge strikes took place across the country, the Communist authorities concluded agreements with the protesters. Thus the workers established “Solidarity”, which would prove to be far more than a trade union dealing with labor and social issues. Union experts, often previously involved in the activities of the democratic opposition, prepared a program for a comprehensive reconstruction of the socialist state. One of the elements of these reforms was the gradual reconstruction of local governments – a basic condition of human rights acts – and also a first step on the path towards changing the Communist system. None of the leaders of Solidarity dared to hope that the Communists, who had the militia and the army at their disposal, would be removed from power. Furthermore, even if the opposition had these forces on their side, the armies of other Communist countries – with the Soviets at the fore – stood ready to intervene militarily to defend the system, as happened in Hungary in 1956 and in Czechoslovakia in 1968. Solidarity members hoped, however, that building grassroots democracy would enable reforms without any fear of military intervention.

During its first nationwide congress in the autumn of 1981, Solidarity adopted its grand program, known as the Self-Governing Republic (Samorządna Rzeczpospolita). Particular emphasis was placed on restoring the mechanisms of democracy while limiting the power of the Communist party: “The Union expects that in the future this control will be exercised by the reborn Sejm and national councils, as well as workers’ unions.” A few weeks later, the union authorities presented further ideas on changing the electoral law for national councils, after which they called on their members to form local groups, select their candidates and create election programs. However, these decisions were adopted shortly before the imposition of martial law on 13 December 1981. In fear of a progressive revolution, the authorities decided to imprison leading trade union activists, send the army onto the street and establish a military dictatorship. This was headed by General Wojciech Jaruzelski, who was also the head of the Communist party, the Prime Minister as well as the Minister of National Defense. Martial law was the antithesis of democracy and self-governance. It wasn’t until 1989 that the idea of local government once again became the subject of political debate.

As a consequence of the compromise of the Round Table in June 1989, and partially free elections, Solidarity introduced its representatives to parliament. In the lower house (the Sejm) they held 35 percent of the seats. In the upper house (the Senate) they had secured exactly 99 percent. General Jaruzelski was surprised by the scale of Solidarity’s success. Meanwhile, the Civic Parliamentary Club – formed by parliamentarians from the Solidarity lists – tried to keep the ball rolling.

Bronisław Geremek, chairman of the Club, put the most emphasis on three demands: granting Solidarity access to the mass media, restoring an independent judiciary, and, finally, changing the law on local government and calling an election. As he explained, “the democratization process is to be conducted from the bottom up.” It was a return to the idea from before martial law; that the boundaries of freedom and democracy needed to be broadened from their foundation, [and be] based on local communities. The realization of these demands became more probable in the face of the weakening position of the Communist party, thus Solidarity succeeded in making its candidate the Prime Minister, namely Tadeusz Mazowiecki, a longtime advisor to the president of the union – Lech Wałęsa. The new Prime Minister, in his expose on 24 August 1989, clearly spoke in favor of the project to rebuild local governments and announced that he would appoint a Minister without Portfolio.

The autumn of 1989 was marked by changes among those holding the greatest power in the country. The new Prime Minister formed the cabinet and gradually expanded the scope of his authority. The Communists found themselves on the defensive, which culminated in the dissolution of the Polish United Workers’ Party. However, the revolution in “big politics” was not reflected at the local level – there the clique that had ruled for years remained in power. One of the leading politicians of Solidarity reported to his colleagues: “what is happening here at the central level, all these democratization changes are not taken into account at the bottom. And in my opinion, this nomenclature, [and] this [Communist] mafia, [all of] these various types of arrangements must be broken by local elections.”

Citizens’ Committees tried to make changes at the local level. Regional branches of Solidarity were established to prepare the campaign before the parliamentary elections in June 1989. Many of these committees did not dissolve, later giving rise to the social movement. Interestingly, their post-election mobilization did not meet with a warm welcome from the Solidarity leadership. The union authorities were more interested in creating a centralized structure than in cooperating with an independent and fragmented social movement. However, social mobilization could no longer be stopped.

In October 1989, about 500 Committees were operating and in December 1989 – over a thousand. At the time, Bohdan Jałowiecki. a sociologist of local communities, assessed that “Citizens’ Committees are poorly structured internally and do not have political power. The bonding is above all, at least verbally, the ethos of Solidarity, the desire for profound changes in social life and the fight against the old order personified previously by the Communist party and now by the nomenclature.” The committees tried to force local authorities to speed up changes, including personnel changes, but, without holding any new elections, their hands were tied. That is why the Committees began to put more pressure on the Prime Minister and the Solidarity leadership.

Prime Minister Mazowiecki did not remain deaf to this call, and he considered it fully justified. He was convinced that building local government was one of the most important political challenges facing his cabinet. He had to find the right man to carry out this difficult reform. The choice fell on Professor Jerzy Regulski, who throughout the eighties had conducted independent research on the local government system. In his opinion, the opposition focused too much on building a civil society: “This way of thinking in the long term had a serious drawback; a total lack of reflection on state reform. It is no accident that Balcerowicz’s reform and our local government came from outside the opposition circles. Mainstream was going in a different direction. And, when in 1989, it suddenly turned out that the democratic opposition was to participate in government, the situation was dramatic. The drawers were empty.”

However, it turned out that Regulski’s drawer was not completely empty. In 1989, he was a member of the Senate, where he was the chairman of the local government committee preparing future reforms. Moreover, he was also the founder of the Foundation for the Development of Local Democracy, aiming to develop a comprehensive reform program. This initiative was politically supported by the US ambassador in Warsaw John Davies, and was co-financed, among others by the British Batory Fund (5,000 pounds) and the National Endowment for Democracy (42,000 dollars). Mazowiecki entrusted Regulski with the function of government plenipotentiary for local government reform. Regulski thus remembered the beginnings: “So I was to take off with an ax to the moon. But I knew that the most important thing was to get started.”

Regulski formed a team and together they began working on the concept of reform. As a person who had many contacts among local Solidarity activists, he confirmed the intuitions of the Prime Minister [regarding the need for local reform]. He pointed out that growing social pressure, widespread signals of the abuse of power by local party machines seeking material benefits, and the lack of legitimacy of current authorities for exercising power, suggested that the elections should be held quickly. Regulski believed that the optimal time was June 1990. Among other things, these conclusions pushed the Prime Minister to act faster. It was quite a surprise, probably even for Regulski, who mentioned years later: “The basic principle of the Mazowiecki’s government’s operation – in all spheres except the economy – was caution (…). The only exception was local government reform.”

At the beginning of January 1990, Mazowiecki gathered a group of his closest advisors – together they decided that political reforms needed to be accelerated. The Prime Minister explained: “We are entering a great period of state reform (…). The state will be changed through the creation of local government as well as through the reform of the state administration. It will be changed at the basic level (…) and its most important and strong foundations will be built.” He clarified that these local government reforms were an opportunity to activate society and include it in the process of building democracy. Mazowiecki’s decisive attitude in this matter was simply amazing.

When the Prime Minister presented his decision at the meeting of the Council of Ministers on 15 January 1990, even members of his cabinet were surprised. Jacek Kuroń, the Minister of Labor and Social Policy and a long-term oppositionist warned: “You cannot do economic, administrative and any other chaos at the same time. No one will be able to get anything done (…) the decision to impose a second revolution on one revolution without preparation is a crazy decision for me.” It certainly was a big challenge. Jerzy Regulski recalled years later: “The entire government administration (…) was against it. They blocked everything.” However, the Prime Minister did not change his opinion. The penny was dropped – President Jaruzelski and the chairman of Solidarity, Lech Wałęsa were also made aware about the idea. The latter even announced it publicly as his initiative. It was no longer possible to retreat.

In the following weeks, thanks to the cooperation of the government and the Senate, it was possible to create a legal framework for reform. At the beginning of March 1990, the parliament adopted an amendment to the constitution introducing a chapter on local government. In the following weeks new legal solutions were developed regulating the system and the division of tasks and competences between government administration and local government. As Regulski recalled: “this is when a triumvirate was created, actually there were four people. I, as the government’s plenipotentiary, Jerzy Stępień as the plenipotentiary of the commission supported by Mirosław Kulesza and Walerian Pańko from the parliamentary extraordinary committee.” Thanks to this, a synergy was achieved, and, thanks to the patronage of Prime Minister Mazowiecki and Speaker of the Senate Andrzej Stelmachowski, the changes were passed quite quickly.

The basic unit of local government was the commune (gmina) – and its inhabitants were given the right to elect councils, which then selected executive authorities. Local elections were scheduled on 27 May 1990. The most popular were the Citizens’ Committees. They had almost 42,000 candidates for councilors (30 percent of all applicants for a mandate). The widespread need for change and social trust could be seen later – every second elected councilor was associated with Solidarity, while a quarter were independent candidates. The only thing that might have been disappointing was the voter turnout – just over 40 percent.

The 1990 elections laid the foundation for the resurgence of local democracy. On the one hand, this was a gigantic change in the functioning of the state. One hundred thousand people were shifted from national government administration to local government, and hundreds of state-owned enterprises and millions of properties were managed by communes. On the other hand, it was a moment when many former democratic opposition activists entered local politics, who even today work for their communities. Unfortunately, later conflicts in the bosom of “Solidarity” cast a shadow on the reform. When Tadeusz Mazowiecki stepped down as Prime Minister at the end of 1990, his local government reform team was dismissed, although they had planned to correct and further develop their project. Jerzy Regulski, the main creator of the success of the reform, used to recall years later: “I have the feeling that some work remains unfinished.”

Author: Tomasz Kozłowski – PhD in political sciences, employee of the History Research Office of Institute of National Remembrance

Transation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin