On 4 April 1794, the Polish army defeated the Russians in the Battle of Racławice. The victory primarily had a symbolic dimension and showed the strength and unity of the nation. It enabled the Kosciuszko Uprising to spread to other regions and became indelibly inscribed in the collective memory of Poles.

by Piotr Bejrowski

At the beginning of April, a week after announcing the insurrection on Krakow’s Main Market Square, Tadeusz Kosciuszko led his troops to confront Russian army approaching from the north, numbering some 6,000 soldiers. The forces were equal in numbers, although the opponents, as a regular army, were definitely more experienced. The insurgent troops numbered circa 4,000 soldiers and almost 2,000 peasants equipped with scythes. These were volunteer troops formed on the basis of a mass movement and armed with battle scythes. As a compact formation, they were first used precisely in the battle of Racławice.

The leader of the uprising did not want succumb to the Russians. He took advantage of the enemy’s division into two groups and decided to engage in battle with General Alexander Tormasov’s troops before they became reinforced and merged with those led by the commander General Fyodor Denisov. Thus, he intended to exploit a numerical advantage which, with good preparation and organisation of the battle, could have offset Russian dominance in terms of equipment.

The first battle of the Kosciuszko Uprising took place at Racławice (presently the Małopolskie Voivodeship). The Polish army was divided into two divisions commanded by Generals Antoni Józef Madaliński and Józef Zajączek, respectively. Tormasov took up a position on a higher, difficult-to-capture hill, which did not foresee success for the Poles, especially as time was not working in Kosciuszko’s favour, the key threat being the consolidation of Russian troops. However, the Russian general allowed himself to be provoked by artillery fire and moved to attack. Had he waited, the fate of the battle would likely have been different, and the uprising would have been suppressed already in early April. The Poles stopped both the flanking attack and the one directed at the centre. The attack of the Cossacks also proved ineffective. Confusion in the ranks of the insurgents, however, was caused by Russian fire. As a result, some of the horsemen fled as far as Krakow, where false rumours about Kosciuszko’s defeat and death had begun to spread.

The turning point in the Polish victory was the wounding and capture of the Russian cavalry commander Colonel Muromcov. However, it was necessary to act quickly, as even before nightfall the first Denisov soldiers were spotted approaching the battlefield. More than three hundred scythemen led by Jan Śląski were placed in the central positions surrounded by four infantry companies. According to tradition, the decisive attack began with Kosciuszko shouting: ‘Forward, boys! Take those cannons! God and the fatherland! Forward, faith!’ The scythes proved a deadly weapon. The Russians were taken by surprise and managed to fire but a few times. Only a dozen peasants were killed. The enemy cannons were captured. One of them was taken by Wojciech Bartos, later known as Głowacki, from Rzędowice, who distinguished himself through particular bravery, allegedly extinguishing the smouldering fuse on the cannon with his cap and becoming a symbol of the Kosciuszko army. The brave peasant is mentioned among the greatest heroes of the uprising. He died two months later as a result of wounds suffered in the Battle of Szczekociny.

Wishing to seal the victory, Kosciuszko sent his cavalry and reserves into battle. The second attack, this time on the enemy’s right wing, involved over a thousand scythemen, who captured more cannons and caused the enemy, while fighting effectively and without mercy, to flee the battlefield. The Russians lost as many as 1,000 killed and twelve cannons. Polish losses were half that amount. In the words of the defeated: ‘Peasants armed with scythes went on the attack with unbelievable valour’. Why did Commander Denisov not come to the aid of the defeated Tormasov? The mutual dislike between the generals was probably decisive. Denisov was a Cossack by origin, while Tormasov was a nobleman and likely not happy about having to follow his orders; hence he decided to rush the battle. Denisov additionally explained himself by the late hour and darkness, losing his way among the hills and news reaching him of the defeat and flight of the Russian forces.

On 5 April 1794, Kosciuszko, in line with his promise made the day before, donned a peasant’s coat, wishing in this way to give additional recognition to the troops that had distinguished themselves most at Racławice. He achieved a tactical victory, yet not his strategic goal, as he failed to break through towards Warsaw. Although the insurgent army returned to Krakow victorious, Kosciuszko faced the task of reorganising the army, reassembling the peasant troops, and preparing another campaign.

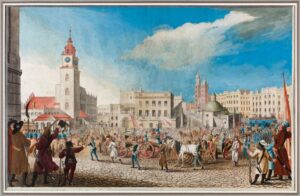

The introduction to Krakow of the twelve Russian cannons captured at Racławice became the subject of one of the works illustrating the Kosciuszko Uprising by Michał Stachowicz, a Polish painter of the Romantic era. The victorious battle, although ultimately of little military significance, was immortalised in art and depicted by the greatest 19th-century Polish painters. One could mention the paintings A Prayer Before the Battle by Józef Chełmoński and Kosciuszko at Racławice by Jan Matejko, the most famous Polish historical and battlefield artist.

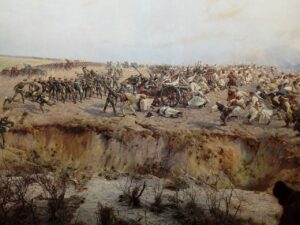

However, these paintings were eventually overshadowed by the work of a team of painters under the direction of Jan Styka and Wojciech Kossak. In 1894, in Lwów, on the centenary of the Kosciuszko Uprising, the first visitors saw the monumental Panorama of Racławice (measuring 1.5 by 11.4 metres). Fortunately, the painting was still in one piece, having survived two world wars, and is now exhibited in Wrocław in a stately rotunda. From the very beginning, The Panorama has attracted great interest and is one of the best recognised artworks in Poland today. It immortalised the Battle of Racławice owing to its patriotic content, which is clear to the masses of viewers. As Styka himself said about the painting, ‘I did not want to honour the triumph of the Polish army, as Poland had bigger victories throughout its history, I only wished to depict that here, a hundred years prior, the whole of the social strata united to defend the Homeland, and I wished to honour the name of the greatest hero of freedom, Kosciuszko’. The Panorama depicts the very climax of the battle – the attack of the Kosciuszko soldiers on the Russian cannons. The viewer is left with no doubt that it had been the bravura attack of the peasants with scythes that had decided on the victory. Instead, they were sent into battle by Kosciuszko, depicted on horseback in a peasant’s dress (and thus contrary to the facts, as he was only to dress in the peasant’s outfit on 5 April of 1794). The painting, along with a mound later built in Krakow, is one of the cornerstones of Kosciuszko’s legend. It presents the leader of the national uprising who was the first to have engaged the peasants in the battle for freedom.

In his work Z dziejów insurekcji 1794 r. (i.e. Of the 1794 Insurgence) published in 1926, the Polish historian Adam Skałkowski concluded that, despite the victory, the battle confirmed that ‘it [was] impossible to face the great tasks of this war with a popular movement, and the insurgents soon realised how unrealistic their objectives had been’. However, it is worth appreciating not only the symbolic dimension of the victory, but also the innovative manoeuvre used by Kosciuszko, who led a decisive attack surprising the enemy with the participation of infantry mixed with peasant forces – poorly armed, untrained, but ultimately deadly and successful. The news of Racławice quickly spread around the country and prompted an extension of the insurgent campaign. More troops joined, led by the Volhynian and Wielkopolska (Greater Poland) divisions. Soon, the uprising spread to almost the entire territory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which had been truncated by Poland’s first and second Partitions – including the territories in Lithuania and behind the Bug River. The victory rekindled the spirit of the nation, and the uncertain and hesitant gave in to the enthusiasm and joined in the fight.

Author: Piotr Bejrowski

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki