There have been few wars in the history of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth so short and so full of sensational twists and turns.

by Michał Wasiucionek

The story of the short but bloody Khotyn War (1620–1621) was full of dramatic twists and turns: from the unexpected and overwhelming defeat of the Crown army at Țuțora (Cecora), through the panic caused by the imminent Ottoman threat and the failed assassination attempt on King Sigismund III, to the gruelling siege of Khotyn, to the peace compromise, and to the death of Sultan Osman II. It is no coincidence that already in the 17th century the history of these struggles enjoyed a great interest in the Commonwealth, to mention only the works of Wacław Potocki and Samuel Twardowski, or numerous printed accounts of the battles.

The dramatis personae of these events included the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire, the Zaporozhian Cossacks, as well as the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. This war can be seen as part of the great continental conflict known as the Thirty Years’ War. However, it also had its own dynamics, embedded in the context of the region, and in internal disputes of various Eastern European states.

The bulwark ready for talks

Although the vision of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as the ‘bulwark of Christianity’ against Turkish expansion has become quite firmly established in public consciousness, the reality of the modern era differed from this stereotypical image. In the times of the last Jagiellonian rulers, dynastic interests and the rulers’ involvement in Hungarian affairs brought the Polish-Lithuanian monarchs closer to the Sublime Porte, as evidenced by the ‘perpetual peace’ agreed with the Ottomans in 1533. Similarly, Sigismund II Augustus also allowed the sale of tin and gunpowder, among other things, in spite of the bans promulgated by the papacy given their importance to military manufacturing.

The policy of avoiding friction with the sultan’s state was not only supported by the Jagiellonians themselves, but also by a significant part of the nobility; the position of the Sublime Porte, strongly opposing the election of the Habsburgs during the first free elections, contributed to preventing the imperial candidate from ascending the Polish throne, a fact that the nobility itself appreciated. The Ottomans were also reluctant to go to war against the Polish-Lithuanian state: involved in wars against the Habsburgs and the Safavids, the Sublime Porte preferred to maintain amicable relations with the third of the great neighbours. Moreover, Ottoman officials were well aware that a possible conflict on the northern shores of the Black Sea would require overcoming considerable logistical effort. The soldiers themselves were by no means keen on partaking in a campaign that would expose them to a climate that the Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi described as ‘frigid hell’ and the chances for rich booty were relatively slim.

The situation began to change at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, the main cause of tension being the inability of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire to keep in check Cossacks and Tatars inhabiting the imperial borderland. Raids against the Polish-Lithuanian frontier settlements, organised by the Crimean khans and the Tatar aristocracy, were by no means a novel phenomenon; however, it was during this period that they increased in intensity, while the colonisation campaign progressing in Ukraine meant that demographic and economic losses were greater than in previous centuries.

At the same time, from the mid-16th century, the Zaporozhian Cossacks began to grow in strength. They soon began to organise their own looting expeditions into Tatar and Ottoman territories, posing a serious threat to the Black Sea ports and Ottoman hold over the entire region. Although in the peace treaties both the Polish rulers and the Sublime Porte pledged to restrain the Cossacks and Tatars, neither side had the tools (and often the goodwill) to work out a long-term solution for the pacification of the region; this was all the more difficult given that both the Crimean Khanate and the Zaporozhians constituted important elements of the armies of both regional powers.

The dispute over Moldavia

In addition, in the early 17th century, other disputes further aggravated Polish-Ottoman relations. Jan Zamoyski’s expedition to Moldavia in 1595, and the installation on the throne of the Movilă family, close to the Polish-Lithuanian elite, renewed the Commonwealth’s claim to sovereignty over this principality, despite the fact that it had been an Ottoman tributary for more than a century; over the following years, relatives and patrons of the dynasty repeatedly intervened in the interests of members of the dynasty, which exacerbated relations with the Porte. Finally, the policy of Sigismund III, which was friendly towards the Habsburgs, also raised fears in Istanbul about a possible Habsburg-Polish coalition. In such a tense atmosphere, any incident could have triggered a large-scale war. Hieronim Otwinowski, an envoy sent to Istanbul in 1619, wrote to the authorities of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth about the bad reception and growing war sentiment among the Ottoman elite, all the more so because, during his stay in the city, the Zaporozhian Cossacks ventured as far as the Bosphorus.

In the circumstances, the authorities of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth decided on an armed demonstration aimed at strengthening Polish-Lithuanian influence in Moldavia, and discouraging the Porte from military action. According to the plan formulated by the Grand Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski, the Crown army was to enter the principality and support the governor Gaspar Graziani, threatened with removal by the Ottomans.

An unexpected defeat

Żółkiewski himself, who took part in Zamoyski’s Moldavian campaigns in 1595 and 1600, maintained numerous contacts with the Moldavian and Wallachian elites, and the Wallachian ruler Gavril Movilă was his former client. Most likely, the campaign of 1620 was intended to demonstrate the determination of the Commonwealth and, at the same time, rebuild the authority of the hetman, who had, in previous years, been heavily criticised for his failures in the battle against the Tatars.

In the summer of that year, Żółkiewski entered Moldavia at the head of a relatively small army, and was joined by Graziani with few supporters. Trying to repeat the success of the 1595 campaign, Żółkiewski dug in at Țuțora on the Prut River, waiting for the enemy and the start of negotiations. This time, however, the expedition ended in complete failure: the initial setbacks led to a complete disarray in the army, further fuelled by disagreements among the command. Some of the soldiers tried to escape across the Prut River at night and drowned; among the fugitives was the unpopular Graziani, who was killed by his boyars while fleeing.

Realising the inevitability of the defeat, Żółkiewski attempted to retreat in the direction of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but on 6 October, the confusion in the camp led to the breakup and a panicky escape of the soldiers toward the nearby border of the Crown. The poorly organised army was attacked by the Tartars; in the course of the battle, the aged Żółkiewski perished, and Field Hetman of the Crown, Stanisław Koniecpolski, found himself in captivity together with numerous officers. It was a total defeat, and the Crown army de facto ceased to exist.

The defeat of Țuțora sent shockwaves throughout the whole Commonwealth, which was, at the time, defenceless against the Tatars and the coming war. Following the Țuțora defeat, Tatar chieftain Kantemir took advantage of the lack of troops in Ruthenia, and completely ravaged the region. The unsuccessful attempted assassination of King Sigismund III by the mentally ill nobleman Michał Piekarski, which took place during a Sejm session in Warsaw, also contributed to the panic; although the King emerged from the attempt with only minor injuries, the failed kingslaying caused a massive commotion in the capital, which was also accompanied by rumours of approaching Tartars.

Taxes and diplomacy

Moved by the danger, the parliament decided to pass high taxes and field 60,000 soldiers. An extensive diplomatic campaign was also undertaken at European courts. The results, however, were disappointing: only King James I of England pledged real help, but the reinforcements he sent did not arrive until after the end of the war; the Habsburgs and the Pope, on whose support they had been counting, were engaged in the Thirty Years’ War, and refused to offer assistance. Foreign conscription encountered serious difficulties, as most soldiers found employment in the armies of the rulers of the Reich; it also quickly became apparent that the collection of taxes was delayed, and instead of the planned 60,000, the Commonwealth would only be able to field half that number, while the mobilisation of troops was dangerously prolonged.

An equally serious problem was the appointment of a commander: the war on Crown lands should have been commanded by the Crown Hetman, but Żółkiewski’s death and Koniecpolski’s captivity ruled out this possibility. In the circumstances, the natural candidate was the experienced Grand Hetman of Lithuania, Jan Karol Chodkiewicz, who had already distinguished himself in battles against the Swedes and during the Moscow campaigns. However, there was a risk that the Crown commanders would not submit to the Lithuanian leader, which could lead to disputes in the command, and a repeat of the Țuțora defeat. In order to avoid misunderstandings, Stanisław Lubomirski was appointed as his deputy, and Prince Władysław also took part in the expedition, whose task – apart from acquiring military experience – was also to attenuate disputes in the command. According to Chodkiewicz’s plans, the army was to cross the Dniester River border, and dig in at Khotyn, thus tying up the Ottoman army and preventing the fighting from spreading to the territories of the Crown.

The news of the Țuțora campaign was received quite differently in Istanbul, especially by the entourage of the young Sultan Osman II (1618–1622). The first decades of the 17th century were a turbulent period in the history of the dynasty, which was in deep crisis. In 1603, after the unexpected death of Mehmed III (1595– 1603), only two representatives of the male members of the dynasty remained; teenage princes Ahmed and Mustafa, whose poor health and lack of descendants raised concerns for the future.

The change in the rules of succession was likely also linked to concerns about the continuity of the Ottoman line; in previous centuries, in order to prevent prolonged civil wars, the prince victorious in a power struggle would dispose of his less talented brothers. Mustafa, however, survived his brother’s rule; after his death in 1617, Mustafa assumed the throne as the brother of his predecessor for the first time, but was soon dethroned in favour of his nephew, Osman II. For the young ruler this situation was by all means uncomfortable: not only did he have to reckon with the fact that his predecessor on the throne was still alive and posed a threat to his power, but also the presence of many potential candidates for the throne could be exploited by influential members of the imperial elite to increase their power.

The inexperienced and ambitious sultan was therefore looking for an opportunity to raise his prestige and consolidate his power; a short, victorious war against a weakened Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth seemed an ideal opportunity to boost Osman’s prestige and reinforce him on the throne. Although speculation about plans to conquer the whole of the Commonwealth as far as the Baltic Sea, or to capture Cracow, may be regarded as fairy tales, the conquest of Podolia or the Palatinate of Ruthenia seemed within reach.

And so it is war…!

Not everyone in the Ottoman Empire was enthusiastic about the prospect of war. There was no shortage of supporters of an amicable solution to the conflict among the highest officials of the Porte; however, the Janissaries, who formed the basis of the empire’s standing army, were particularly reluctant to go to war. In the period leading up to the Khotyn War, this select corps grew considerably, absorbing many members from among craftsmen and merchants, who sought to enter the ranks of the empire’s elite, and enjoy the privileges associated with such status.

This did not automatically mean the decline of the fighting ability of the Janissary units, which, during the ‘Long War’ with the Habsburgs (1596-1606), quite quickly adopted the tactical innovations associated with the military revolution. Nevertheless, in the course of these changes, the Janissaries ceased to be merely a military unit, and became a powerful group of influence, fiercely defending their interests against the sultan and dignitaries of the empire.

Last but not least, an invisible enemy was also working against the sultan’s plans – the climate. The winter of 1621 was a critical moment of the ‘little ice age’, which began in the 1590s, and lasted throughout the 17th century; low temperature significantly reduced harvests, and chroniclers noted that the freezing of the Bosphorus made it impossible to supply the capital, which in turn caused a wave of famine in Istanbul.

Climatic changes also had a direct effect on preparations for the campaign, as food shortages made it difficult to supply military stores along the route of the march, and a delayed growing season and fodder shortages prevented numerous cavalry units from setting out early. Nevertheless, in the summer of 1621, Osman II, at the head of an army of around 100,000, set off toward the north, hoping for a quick victory over the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Trouble with the Cossacks

Meanwhile, in view of the difficulties in rebuilding the Crown army, it became of great importance for the Commonwealth to enlist Cossack support. However, this was not easy; in the years preceding the outbreak of the war, conflicts between the Polish-Lithuanian state and the Zaporozhians concerned the size of the Cossack register, as well as their arbitrary expeditions into Ottoman territories. Attempting to maintain peace with the Sublime Porte, Stanisław Żółkiewski and other Crown officials tried to stop the Black Sea expeditions and burnt Cossack boats, which aroused understandable opposition from the Zaporozhians. In addition, for financial and political reasons, they refused to enlarge the Cossack register, i.e. the census of Cossacks endowed with personal liberty and receiving pay, even though the number of those fighting on the side of the Commonwealth increased significantly during the Polish-Muscovite wars and the intervention of Sigismund III in Moscow.

These difficulties were compounded by religious issues; the Cossacks were increasingly clearly positioning themselves as defenders of the Orthodox Church against the Union of Brest’ supported by Sigismund III, which found its expression in particular when the Orthodox hierarchy in the Commonwealth was restored by Patriarch Theophanes of Jerusalem (1620). This divergence between the interests of the Polish-Lithuanian state and the Cossacks made cooperation difficult, but it was nevertheless necessary for the Commonwealth in view of the prospect of an Ottoman attack.

Fortunately, the Polish-Lithuanian authorities found a willing collaborator in Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny, who enjoyed considerable authority among the Cossacks and, during the war, played a major role in mobilising the Zaporozhians on the side of the Commonwealth. During the battles in Moldavia, at Khotyn, and on the Black Sea, the Zaporozhian army would play a key role, and contribute significantly to the outcome of the war.

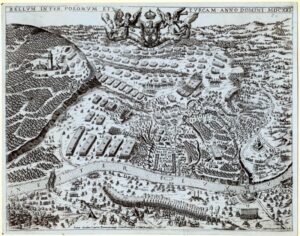

The Polish-Lithuanian army was the first to arrive at Khotyn and began construction of a fortified camp based on the old Moldavian castle on the banks of the Dniester; communication with the Commonwealth and the Kamianets fortress was to be provided by a bridge across the river, around which fierce battles would take place. Literally on the eve of the confrontation, some 30,000 Cossacks also arrived at Khotyn, but there was not enough room for them in the Polish camp; they set up a separate one on the neighbouring plain. Chodkiewicz’s plan, supported by the war council, was to avoid a decisive battle and exhaust the enemy, but a serious problem in its implementation was the shortage of food and ammunition, which was even more acute in the case of the Cossacks.

On 2 September, Ottoman troops began arriving at Chocim, and attempted to attack Polish positions, but were quickly repulsed. Encouraged, Chodkiewicz planned to give the enemy an open field battle but was dissuaded from this by the other commanders. Meanwhile, spirits were falling in the Ottoman army, which was also due to by Osman II himself, who, on his way to Khotyn, decided to review the Janissary troops, and exclude those who did not show up for the campaign, which provoked protests from the soldiers, and caused them to feel despondent toward the sultan. Morale was also negatively affected by supply problems, and conflicts among commanders, which hampered the war effort.

Wanting to break the defenders’ resistance as quickly as possible during the first few days of battle, Ottoman soldiers tried to storm the camp, but were repulsed each time with heavy losses. After a general assault on 8 September, Osman and his advisors came to the conclusion that their chances of taking the well-fortified Polish-Cossack positions were slim, and it was decided to launch a prolonged siege. This meant the failure of the sultan’s ambitious plans, as the prolonged siege and deteriorating weather reduced the chances of significant territorial gains during the campaign. Only Tartar troops marched beyond the Dniester and, taking advantage of the confinement of most of the Crown troops in the Khotyn camp, they completely devastated the borderland. Soon, both camps started running out of food, and supplies of ammunition and gunpowder began to dwindle dangerously.

During the siege, the army of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth suffered another significant loss as, although Chodkiewicz’s efficient leadership during the battle contributed to the success of his army, the hetman’s health began to deteriorate rapidly. Bedridden and aware of his imminent death, he handed over command of the army to his deputy Stanisław Lubomirski, and died soon after, on 24 September 1621; the news of his death could not be concealed, but the trust shown in Lubomirski by Prince Władysław and the other commanders helped maintain morale among the troops, who continued to repel the Ottoman attacks.

The following day, in an attempt to take advantage of the enemy’s weakened position, the Ottoman command launched an attack on the weakly fortified ‘Lisowczyki’ light cavalry positions, which was, however, resisted with heavy losses for the attackers; the final general assault three days later headed in the same direction. At this stage, Osman and his commanders were concerned almost exclusively with achieving a symbolic victory, because, due to the late season, there could be no further conquests. The failure of the attack on 28 September finally convinced the sultan that there was no point in further fighting, and opened the way for negotiations. The Crown army was also at its limits: there was only one barrel of gunpowder left in the camp, and supplies from nearby Kamianets did little to improve the situation.

Negotiations in four languages

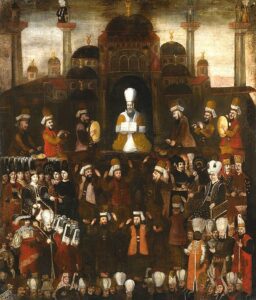

Negotiations between the two sides had been continuing for some time, mainly through the Wallachian Prince Radu Mihnea and his diplomat, the Cretan Constantin Vevelli, but now they entered a new phase, and commissioners were sent to the sultan’s camp to negotiate a truce; Stanisław Żórawiński and Jakub Sobieski (the father of the future King of Poland).

Negotiations were not easy, not only because of the divergent demands of both sides, but also owing to language differences. The Polish commissioners spoke in Polish, the interpreter translated the content to the Romanian ruler, who in turn translated it into Turkish, which naturally prolonged the talks. The main points of contention concerned the issue of taming the Cossacks and the Tatars, as well as the issue of the payment of the tribute by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which the Polish commissioners refused to agree to.

The establishment and translation of the content of the treaty posed similar practical problems, as the individual points had to be translated three times each time, from Polish into Romanian, then into Greek, and only then into Turkish. Paradoxically, these linguistic difficulties facilitated agreement: the Polish version of the treaty, finally agreed on 9 October 1621, mentioned traditional gifts for the khan, while the same paragraph in the Ottoman version interpreted the same gifts as a tribute. With this change, each side could declare victory in negotiations.

Both sides also pledged to cease raids, and to recognise Ottoman sovereignty over the disputed Moldavia. On 9 October, the army of Osman II began to retreat southwards, thus ending a devastating campaign. Meanwhile, in order to confirm the peace, a great envoy was to be sent to Istanbul to receive the sultan’s ahdname (imperial edict). Peace was finally sworn in 1623, yet the ruler issuing the document was not Osman II but his younger half-brother Murad IV.

Despite the ambiguous wording of the Khotyn Treaty, there was no doubt that Osman II’s war plans failed. Not only did the expedition bring considerable human losses without any territorial gains, but it also irreparably damaged relations between the ruler and the Janissaries, whom the sultan blamed for the disappointing outcome of the campaign. On his return to Istanbul, relations by no means improved, and the sultan himself declared his intention to go on pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. This was an unprecedented step, as none of the previous Ottoman rulers had visited the holy cities of Islam; the determination of the young Ottoman also aroused suspicions that the journey was not dictated by piety, but aimed at forming a new army in Anatolia and getting rid of the Janissaries, who had disappointed the ruler so much during the Khotyn campaign.

In spite of objections, the sultan pushed ahead with his plan, but eventually, under pressure from the Janissaries and Sublime Porte dignitaries, abandoned the unpopular venture. Too late, though: on 16 May 1622, the Janissaries stationed in Istanbul revolted against his rule and, within three days, removed him from power, elevating his uncle Mustafa to the throne for the second time. The dethroned ruler was imprisoned at the fortress of Yedikule and subsequently murdered; this was the first regicide in the history of the Ottoman Empire. Mustafa himself did not last long on the throne either, as he was deposed the following year, and the brother of the murdered Ottoman – Murad IV – proclaimed the new sultan.

Author: Michał Wasiucionek

Translation: Mikołaj Sekrecki