Józef Sułkowski (Joseph Sulkowski) was an aide-de-camp to Napoleon Bonaparte, and a participant in the Italian and Egyptian campaigns. He was a radical republican and simultaneously an extremely courageous man with broad horizons, a talented and ambitious officer, and the author of interesting memoirs for whom, in his own words, ‘war glory and freedom were everything’.

by Piotr Bejrowski

Born in Rydzyna in Wielkopolska (Greater Poland) on 17 or 18 January 1773, Sułkowski’s paternity is attributed to Bishop Michał Jerzy Poniatowski. The boy was brought up by his uncle, Prince August Sułkowski, Ordinate of Rydzyna. From his earliest years, Napoleon’s future aide-de-camp loved talking about the military, fortresses, battles, and the history of military operations. As a teenager, he became a cadet of the Riga regiment and joined the Order of Malta. In 1786, he was promoted to lieutenant, and to captain five years later.

In the era of the Great Sejm (1788–1792), Sułkowski radicalised his views and broke with his noble lineage. He read the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, joined the Polish Jacobins, and criticised the Constitution of 3 May 1791, calling it ‘timid, incomplete and too ductile’. He was particularly outraged by the principle of the succession of the throne, but nevertheless fought against Russia in the war of 1792. For his bravery ‘he was awarded the Virtuti Militari Cross for stopping the charge of four hundred Cossacks with only thirty riflemen’. His superior described him as ‘excellent in combat’, a man who ‘always put himself at risk’ and was ‘full of bravado and ability’.

After King Stanisław August Poniatowski joined the Targowica confederation, he resigned immediately and left for France, where, not without problems (he was even briefly imprisoned), he blended into the revolutionary milieu. After being granted French citizenship, he learnt Arabic and Turkish, was sent on a diplomatic mission to Constantinople, and later joined the Army of Italy commanded by Napoleon. Sułkowski is said to have quickly become acquainted with the ambitious general and, in a letter to Michał Kleofas Ogiński, claimed that Bonaparte would ‘sooner or later not fail to stand at the helm of the government’.

Napoleon quickly became convinced of the Polish officer’s military and management talents. As the Jacobin biographer Marian Brandys wrote, ‘he ceased to regard the suspicious dandy from Paris as an informer, and recognised in him a fearless soldier’. In October 1796, Sułkowski became aide-de-camp to the future French Emperor, and his ratings were further boosted when he demonstrated his heroism at the Battle of Arcole. And even though, after a conflict with Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, the founder of the Polish Legions in Italy, he ceased to be Bonaparte’s first Polish advisor, he continued to maintain a high position, promising an illustrious career in the years to come.

An opportunity for Sułkowski, who was well versed in Middle Eastern affairs, was the Egyptian expedition led by Napoleon. Its scientific (the general took more than 150 scientists with him) and military perspectives, as well as its adventurous and romantic aspects, were ideally suited to the nature of the Polish officer, who was one of the main people responsible for organising the campaign. On 19 May 1798, the French fleet set sail from Toulon. On his way up the Nile, Bonaparte stopped in Malta. The Knight of Malta Sułkowski took part in the capture of the island, which was governed by the Joannites.

Sułkowski distinguished himself during the siege of Alexandria and in the famous Battle of the Pyramids, where ‘with old-fashioned fantasy he flew out before the battalion front, to scout one-on-one with armoured Egyptian horsemen’ (Brandys). He basked in glory once again on 11 August when fighting against Ibrahim Bey’s cavalry. Despite the disproportion of forces, at the head of two squadrons, he charged repeatedly at the troops of the Mameluke cavalry. Finally hit by bullets from pistols and cut by a sabre, he fell seriously wounded. After healing, already in the rank of colonel, he was assigned to the natural history and political economy section of the Egyptian Institute. He worked on the concept of the Suez Canal and on the preparation of an Arabic-French dictionary. He was also involved in archaeological work and, as part of a special committee, in collecting information on how to improve Egyptian legislation and education.

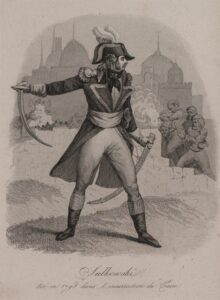

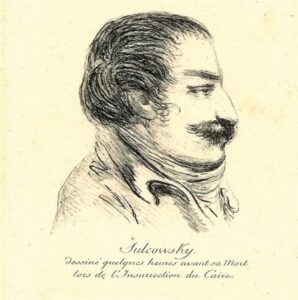

On 21 October 1798, a revolt broke out in Cairo on the news that Turkey had joined the war against revolutionary France, during which the Polish Jacobin was killed. His final moments were recounted by a chronicler of the campaign: ‘Brigade chief Sułkowski left at dawn with a detachment of scouts to reconnoitre the road […]. A terrible and irrevocable destiny awaited him at the gates of Cairo. [Too brave to count his enemies, the young Pole rushed upon them with his weak escort; he had already cleared the way with sabre in hand […] when his horse, slipping on corpses, fell and threw him off. Sułkowski, still suffering from his recent wounds, had neither the time nor the strength to stand. The crowd unleashed its fury on him, and he was massacred before the scouts had time to rush to his aid.’

Sadness at his death was widespread, for the Pole was well-liked both in the army and among scholars. Vivant Denon, the draughtsman of the Egyptian expedition, claimed that ‘he was the officer I loved most’. In a report to the French authorities, Bonaparte noted: ‘After his horse slipped, Sułkowski suffered a cruel death… He was an officer of the greatest hopes.’

His death was a kind of memento for the thousands of Poles who were to give their lives up for Napoleon over the following years. Perhaps Sułkowski’s death by trampling was to Bonaparte’s advantage. One chronicler of the expedition wrote that the aide-de-camp ‘judged his superior with sometimes extreme severity’, and, as a result, the latter reportedly no longer wished to cooperate with the Pole. However, it is difficult to blame the future emperor for the actions of the Cairo mob. The version stating that the future French Emperor was responsible for the death of his comrade-in-arms, however, is still rooted in Poland, inter alia, thanks to Brandys’ book Oficer największych nadziei (‘Officer of the Greatest Hopes’), whose author believed that Sułkowski’s cooperation with Bonaparte must have ended in Egypt just as it had. For a man of such stature and format as Sułkowski, this was the only and inevitable solution’.

The figure of the Polish revolutionary has become firmly entrenched in the culture. The officer is the title character of Stefan Żeromski’s drama Sułkowski (1910) and the predominant figure of three battle paintings by Stanisław Eugeniusz Bodes from the series Glory to Heroes – History of the Polish Armed Forces. The name of Bonaparte’s aide-de-camp was commemorated on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, and an obelisk was erected at the site of his last battle in 1834, demolished a few months later by Cairo paupers, informing the public in three languages of the death of a man who could have played a much greater role in the Napoleonic era.

Several years following the failed Egyptian campaign, already as emperor, Napoleon is purported to have said of his former protégé: ‘Sułkowski would have gone far… He was a man invaluable to anyone who would undertake the resurrection of Poland…’ Incidentally, he continued to recall the talented aide-de-camp on the island of Saint Helena.

Author: Piotr Bejrowski

Translation: Alicja Rose & Jessica Sirotin