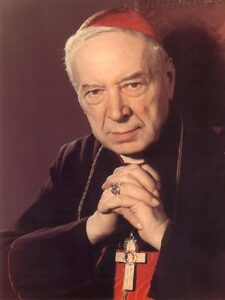

Poland bids farewell to a hero not wearing a crown or a general’s uniform but a priest’s cassock. We bid farewell to the one who achieved the greatest victory in the 20th century, although his only weapon was the cross, his only strength faith and his only army the defenceless but faithful Polish people. This is how Jan Nowak Jeziorański informed the listeners of Radio Free Europe 40 years ago (on 28 May 1981) about the death of Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński. Rafał Łatka, a historian and political scientist from the Historical Research Office of the Institute of National Remembrance, talks about the role of the Polish primate in the fight against communism.

Polish History Museum (PHM): Already in 1945, when the communists terminated the concordat binding Poland with the Holy See, it became clear that a conflict between the authorities and the Church was inevitable. Primate August Hlond was convinced that it would not be possible to plant communism in Poland for any longer, because the world would not allow this ideology to triumph in Europe. What was the opinion of his successor?

Rafał Łatka: Primate Stefan Wyszyński’s attitude towards the new authorities was much more realistic than that of his predecessor, who was not fully aware of the consequences of implementing and functioning of the communist ideology in the Soviet Union. Unlike Cardinal Hlond, Primate Wyszyński was an excellent expert in Marxist-Leninist ideology and understood the mechanisms of its reception in the USSR. As a priest, he had often conducted classes for workers, so he knew how to react to concrete issues related to economic problems, and was able to outline the attitude of the Church in a way that was credible to the faithful. He was therefore well prepared to fulfil his function in the very difficult period ahead. One can risk a statement that in a democratic system it could have been different, while under communist rule Primate Wyszynski ‘proved himself’ optimally.

PHM: How did Stefan Wyszyński’s realistic outlook translate into his relations with the communist authorities?

Rafał Łatka: Initially, Primate Wyszyński adopted an attitude that one should come to an agreement with the communists. There were, of course, principles about which he did not make concessions – above all, those concerning having full control over Church structures. However, he was able to accept to give in on issues less fundamental for the Church. He believed that it was better to make concessions in secondary matters, and to concentrate on ensuring that the Church could function at all. This position resulted in the conclusion of an agreement with the communist authorities in April 1950, in which the Episcopate undertook, among other things, to condemn the activities of the underground and not to resist the collectivisation of rural areas.

PHM: The text did indeed mention, among other things, recognition of the new authorities or condemnation of the ‘criminal activity of the underground bands’. Concluding such an agreement was a bold move on the part of the primate. How was it received by the public?

Rafał Łatka: Indeed, the conclusion of this agreement aroused much controversy. Already at the moment of its signing, the primate did not have much support in the Episcopate. There was fundamental resistance among the Polish clergy. The Holy See also reacted strongly: Cardinal Domenico Tardini, a high official of the Roman Curia and later the Secretary of State in the Vatican, spoke very harshly on the subject, believing – somewhat rightly – that the Episcopate had no right to conclude such an agreement without the consent of the Holy See. There was no such consent and probably there could not have been (the pope being unaware of the plans of the Polish primate). Finally, the agreement was quite strongly criticised by the independence-minded circles in exile, who thought that the primate had betrayed the Polish society. The agreement thus remained a rather bold and risky step, and its consistent supporters were basically only those bishops who signed it.

PHM: It soon became apparent that the communist authorities had no intention of honouring it, so Wyszynski changed his attitude and, together with the Polish bishops, issued the famous ‘Non possumus’ memorandum. How did this affect relations between the Church and the authorities?

Rafał Łatka: The communists treated the letter from the Polish bishops almost as a declaration of war. It included an entire catalogue of wrongs inflicted on the Church by the state, which provoked fury in the party leadership and provoked further repressions. This happened after only a few months. The show trial of Bishop Kaczmarek and the arrest of Wyszyński in September 1953 were examples of this. To this day, we do not know exactly when the decision to intern the primate was made. But we know for sure that it was taken by the Polish communists and put into effect during the Kremlin interregnum (after Stalin’s death), when they were sure that nobody would be able to prevent them from doing so. This was because earlier the USSR authorities had advised against such a step. Stalin was aware that the arrest of the Polish primate would be counterproductive creating a new martyr.

PHM: In other countries of the socialist bloc, clashes between Communists and Church leaders occurred much earlier and were more severe. The Hungarian primate Archbishop József Mindszenty was arrested as early as 1948 and after two months of torture sentenced to life imprisonment. The same happened to the heads of the Croatian or Czech Church. Why was it different in Poland?

Rafał Łatka: It seems that the key factor was the strength of the Polish Church, the fact that the Catholic faith was completely dominant in Poland. The communists’ tactics stemmed from the conviction that the opposition had to be smashed first and only then could the next enemy be dealt with. This, in a nutshell, was what is referred to as the salami tactic, which involved making successive segments of the social structure gradually dependent on the communist authorities. In Poland, the focus on the Church came later – for the power of the underground was considerable, and even more powerful was the legally existing opposition centred around the Polish People’s Party (PSL) led by Stanisław Mikołajczyk. Only after dealing with them could the communists deal with the Church. But other facts were also important: the Church in Poland had prepared well for the fight against communism, if only by strong centralisation – thanks to special powers from the Holy See, a decision taken by the primate was practically irrevocable, which under normal conditions in the Church system could not have happened. Let us not forget the approach of Wyszyński himself, who reacted to successive repressions with a gradual withdrawal. The Church under his leadership tried not to provoke the authorities and stepped out of the line of fire. That is why the communists initially tried to pursue a policy of repression without arresting Wyszyński. Only when they became convinced that he was such a strong leader that the Church could not cope without him did they change their tactic.

PHM: Did this tactic have the intended effect? How did Poles perceive the arrest of the primate?

The policy of appeasement did not win Wyszyński many supporters in the Polish Church, so at the moment of his arrest he was very much alone. As he later recalled, he was defended only by a German and a dog – the German being Father Wojciech Zink, the only priest in the Episcopate who protested against the primate’s arrest, and the dog the one that bit one of the secret police officers. Perhaps that is why the scale of the protest of the ‘ordinary’ Polish public against the arrest of the primate surprised the communists. They were also astonished by the strong and unambiguously negative international reaction – protests against the internment of the Polish primate were issued by almost all countries of the free world. The Holy See reacted quickly and firmly with a decision to excommunicate all those involved in his arrest. However, the Polish bishops failed, signing a declaration suggested to them by Bolesław Piasecki, the leader of the PAX Association. The primate himself did not agree to sign it, while the bishops made far-reaching concessions and behaved fearfully and amicably. As Wyszyński later recalled, they did not use the social outrage to effectively manifest their opposition. It was only at the turn of 1955 and 1956 that they made real efforts to have Wyszyński released, and they did, but this was due not to the decisions and actions of the bishops, but to the political changes in Warsaw in the autumn of 1956. At the end of October, Wyszyński made a triumphant return to the capital.

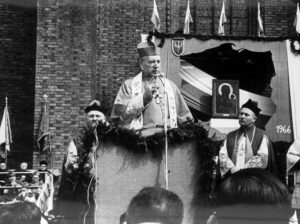

PHM: One of the most important undertakings of Primate Wyszyński was to organise the Great Novena of the Millennium of Poland’s Baptism, the greatest pastoral project of the Polish Church. How did the communist authorities react to it?

The primate took perfect advantage of the weakness of the communist authorities in the period of the Thaw. He prepared the programme of the Great Novena, as well as the earlier Jasna Góra Vows, while still in custody. These initiatives were very important not only in religious terms. A significant part of the Jasna Góra Vows was much more social and national than pastoral. The programme lasted nine years, culminating in the 1966 celebrations of the Millennium of Poland’s Baptism, for which Poles basically voted with their feet. Hundreds of thousands of the faithful took part in the church celebrations, while in rival celebrations, organised by the communists, the attendance was significantly lower. This was proof of who was winning the battle for ruling people’s hearts and minds in Poland. The programme’s role went far beyond millennial celebrations. Its influence on the self-identification of Poles and their sense of independence from the communists paved the way for the development of independent initiatives in the 1970s. One might even venture saying that it was partly thanks to Wyszyński’s actions that August 1980 and the birth of Solidarity became possible.

PHM: However, Wyszyński himself was initially rather distrustful towards the Workers’ Defence Committee (KOR) or the generation of March 1968 protesters.

Wyszyński’s aversion to the KOR circles stemmed from his knowledge of the Committee leaders’ Marxist past and affiliation with the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR), as well as from the primate’s conviction that they demanded too far-reaching changes in the political system. Already as Bishop of Lublin, Stefan Wyszyński was of the opinion that a sharp, direct fight with the communist authorities did not make sense, as it would not help Polish aspirations in any way, but on the contrary – would cause unnecessary bloodshed. For this reason, he appealed for self-restraint. A similar approach can be seen in the famous homily delivered at Jasna Góra on 26 August 1980, in which the primate called for prudence and responsibility. It is characteristic that it was misunderstood by a section of society – the communist authorities manipulated its meaning in the media, whereas the strikers expected total support and received only conditional backing. Despite this cautious approach, the primate was deeply convinced that right was on the side of the workers, and that the right to self-organisation and the creation of structures independent of the authorities was their natural right. This was quickly recognised by Solidarity activists, who made the primate (and the Church) one of the main points of reference in their activities. Wyszyński’s success was undoubtedly the fact that the activists of Solidarity referred to Catholic values in what they did, considering them an important element of self-identification. In this way, Wyszyński’s years of building a Catholic identity in Polish society were crowned. At the end of his ministry, they bore wonderful fruit.

PHM: Researchers sometimes perceive Stefan Wyszyński as a continuator of the function of an interrex, which originated in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth – a figure who exercised power in the country during the interregnum. Rightly so?

We could say that Primate Wyszyński was the spiritual leader of Poles, indeed – a kind of an interrex, although he himself consistently avoided this term. He saw himself above all as a priest and teacher. He became a statesman or a leader of the nation out of necessity, though indeed it is not unreasonable to call him so. He was involved in political activities, engaged in dialogue with communists, and tried to force them to make concessions not only in favour of the Church, but also for the good of society as a whole. He was present at all political crises and the authorities had to reckon with him. All this made Wyszyński grow into a spiritual leader, one shaping the nation. His great success was in sowing the seed that produced a generation of Poles who thought differently from what the authorities wanted. This, in turn, made the final victory over communism possible.

Interviewer: Natalia Pochroń

Transation: Mikołaj Sekrecki